Use of Second Generation Supraglottic Airway Device for Endovascular

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paramedic Airway Management Course

Pierce County EMS Paramedic Airway Course 2nd Edition September 2012 Pierce County EMS Paramedic Airway Management Course Table of Contents: Acknowledgements ............................................................................................ 3 Course Purpose and Description ..................................................................... 4 Background ........................................................................................................ 5 Assessing the Need for Emergency Airway Management ............................. 6 Effective Use of the Bag-Valve Mask ............................................................... 7 Endotracheal Intubation—Preparing for First Pass Success ........................ 8 RSI & Endotracheal Intubation ....................................................................... 11 Confirming, Securing and Monitoring Airway Placement ............................ 15 Use of Alternative “Rescue Airways” ............................................................ 16 Surgical Airways .............................................................................................. 17 Emergency Airway Management in Special Populations: ........................... 18 Pediatric Patients Geriatric Patients Trauma Patients Bariatric Patients Pregnant Patients Ten Tips for Best Practices in Emergency Airway Management ................ 21 Airway Performance Documentation and CQI Analysis ............................... 22 Conclusion ...................................................................................................... -

EMS Patient Care Procedure Documents for NC EMS Systems

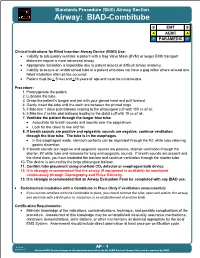

Standards Procedure (Skill) Airway Section Airway: BIAD-Combitube B EMT B A AEMT A P PARAMEDIC P Clinical Indications for Blind Insertion Airway Device (BIAD) Use: Inability to adequately ventilate a patient with a Bag Valve Mask (BVM) or longer EMS transport distances require a more advanced airway. Appropriate intubation is impossible due to patient access or difficult airway anatomy. Inability to secure an endotracheal tube in a patient who does not have a gag reflex where at least one failed intubation attempt has occurred. Patient must be > 5 feet and >16 years of age and must be unconscious. Procedure: 1. Preoxygenate the patient. 2. Lubricate the tube. 3. Grasp the patient s tongue and jaw with your gloved hand and pull forward. 4. Gently insert the tube until the teeth are between the printed rings. 5. Inflate line 1 (blue pilot balloon) leading to the pharyngeal cuff with 100 cc of air. 6. Inflate line 2 (white pilot balloon) leading to the distal cuff with 15 cc of air. 7. Ventilate the patient through the longer blue tube. Auscultate for breath sounds and sounds over the epigastrium. Look for the chest to rise and fall. 8. If breath sounds are positive and epigastric sounds are negative, continue ventilation through the blue tube. The tube is in the esophagus. In the esophageal mode, stomach contents can be aspirated through the #2, white tube relieving gastric distention. 9. If breath sounds are negative and epigastric sounds are positive, attempt ventilation through the shorter, #2 white tube and reassess for lung and epigastric sounds. -

Emerging Uses of Capnography in Emergency Medicine in Emergency Capnography Uses of Emerging

Emerging Uses of Capnography in Emergency Medicine WHITEPAPER INTRODUCTION The Physiologic Basis for Capnography Capnography is based on a discovery by chemist Joseph Black, who, in 1875, noted the properties of a gas released during exhalation that he called “fixed air.” That gas—carbon dioxide (CO2)—is produced as a consequence of cellular metabolism as the waste product of combining oxygen and glucose to produce energy. Carbon dioxide exits the body via the lungs. The concentration of CO2 in an exhaled breath reflects cardiac output and pulmonary blood flow as the gas is transported by the venous system to the right side of the heart and then pumped into the lungs by the right ventricle. Capnographs measure the concentration of CO2 at the end of each exhaled breath, commonly known as the end- tidal carbon dioxide (EtCO2). As long as the heart is beating and blood is flowing, CO2 is delivered continuously to the lungs for exhalation. An EtCO2 value outside the normal range in a patient with normal pulmonary blood flow indicates a problem with ventilation that may require immediate attention. Any deviation from normal ventilation quickly changes EtCO2, even when SpO2—the indirect measurement of oxygen saturation in the blood—remains normal. Thus, EtCO2 is a more sensitive and rapid indicator of ventilation problems than SpO2.1 Why EtCO2 Monitoring Is Important It is generally accepted that EtCO2 monitoring is the practice standard for determining whether endotracheal tubes are correctly placed. However, there are other important indications for its use as well. Ventilatory monitoring by EtCO2 measurement has long been a standard in the surgical and intensive care patient populations. -

Basic Airway Management & Decision Making

Roberts: Clinical Procedures in Emergency Medicine, 5th ed. CHAPTER 3 – Basic Airway Management and Decision-Making Robert F. Reardon, Phillip E. Mason, Joseph E. Clinton Over the last few decades, several important changes have occurred in emergency airway management. Bag-mask ventilation has been supplemented by intermediate, or backup, ventilation devices like the laryngeal mask airway (LMA), the Combitube, and the laryngeal tube. These have become important devices for the initial resuscitation of apneic patients and for rescue ventilation when intubation fails.[1] Noninvasive positive-pressure ventilation (NPPV) is now used in place of tracheal intubation in some critically ill patients. Despite these advances, basic techniques such as opening the airway, oxygenation, and bag-mask ventilation remain the cornerstones of good emergency airway management. [2] [3] Airway maintenance without endotracheal intubation is one of the most important emergency [4] airway management techniques to keep patients alive until a definitive airway can be established. This chapter describes basic airway skills including opening the airway, O2 therapy, NPPV, bag-mask ventilation, and intermediate ventilation devices. Because of the complexity of these skills and decisions, providers should develop a simple, organized approach to emergency airway management, being cognizant that when a specific intervention has failed, it is time to move rapidly to a different approach. Developing a simple preconceived algorithm that employs proven techniques and is applicable to a broad range of clinical scenarios will help providers manage difficult, anxiety-provoking emergency airways. THE CHALLENGE OF EMERGENCY AIRWAY MANAGEMENT Although other specialists are sometimes available, most emergency airways are managed by emergency clinicians.[5] Airway management in the emergency department (ED) is much different from airway management in the controlled setting of the operating room. -

Bag-Valve Mask Ventilation” Page 1

FDNY–EMS CME JOURNAL 2009_J01 “Back to the Basics”: BAG -VALVE MASK VENTILATION lthough all airway skills are important, the most important skill, and perhaps the most difficult, is the ability to use a bag and mask to effectively oxygenate and ventilate a patient. While over A the years there have been important advances in emergency airway management, such as alternative airways (e.g. Combitube), Bag-Valve Mask (BVM) ventilation is a life-saving skill that is often underappreciated. While BVM ventilation may seem mundane compared to placing an advanced airway (e.g. endotracheal tube, Combitube), it is actually a skill that is difficult to master. The false belief that BVM ventilation is an easy skill has led many health-care providers to mistakenly think they are proficient in this skill. The purpose of this article is to review BVM ventilation and associated skills and techniques to effectively ventilate a patient. In the second half of this article is a review of some of the advanced airway tools and techniques. While most applicable for Advanced Life Support (ALS) providers, it is beneficial for all personnel to have an awareness of them. Proper positioning of the patient is a critical element for successful BVM ventilation. The classic teaching for both ventilation and intubation positioning is placing the patient in the “sniffing position” provided there are no spinal precautions that need to be taken. The purpose is to allow for proper alignment of the oropharyngeal axes (Figure 1). Figure 1 FDNY–EMS CME Journal 2009_J01 “Bag-Valve Mask Ventilation” Page 1. However, this still may be inadequate, especially for pediatric and obese patients. -

This Procedure Includes the Following: • Endotracheal Intubation (Plus Use of Supraglottic Airway Laryngopharyngeal Tube (S.A

ADVANCED AIRWAY PROCEDURES This procedure includes the following: Endotracheal intubation (plus use of Supraglottic Airway Laryngopharyngeal Tube (S.A.L.T. device), gum elastic bougie assisted tracheal intubation, video laryngoscopy) Non-Visualized Airways (Dual lumen airway, King LT-D™ Airway, Laryngeal Mask Airway (LMA)) Cricothyroidotomy – needle and surgical GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS Rescuers must be aware of the risks and benefits of advanced airway management techniques. In cases of cardiac arrest the insertion of an advanced airway may require interruption of chest compressions for many seconds, the rescuer should weigh the need for compressions against the need for insertion of an advanced airway. Rescuers may defer insertion of an advanced airway until the patient fails to respond to initial CPR and defibrillation attempts or demonstrates return of spontaneous circulation. Providers should have a second (back-up) strategy for airway management and ventilation if they are unable to establish the first-choice airway adjunct. Bag-mask ventilation may provide that back-up strategy. ENDOTRACHEAL INTUBATION A. Indications for emergency endotracheal intubation are: 1. Inability of the rescuer to adequately ventilate the patient with a bag-mask device 2. The absence of airway protective reflexes (coma and cardiac arrest) B. In most case, endotracheal intubation provides definite control of the airway. Its purposes include: 1. Actively ventilating the patient 2. Delivering high concentrations of oxygen 3. Suctioning secretions and maintaining airway patency 4. Preventing aspiration of gastric contents, upper airway secretions or blood 5. Prevented gastric distention due to assisted ventilations 6. Administering positive pressure when extra fluid is present in alveoli 7. Administering medications during resuscitation for absorption through lungs as a last resort C. -

Complications Associated with the Esophageal- Tracheal Combitube

124 REPORTSCANADIAN OF JOURNALORIGINAL OFINVESTIGATIONS ANESTHESIA Complications associated with the Esophageal- Tracheal Combitube® in the pre-hospital setting [Complications associées avec l’utilisation du Combitube dans la prise en charge des arrêts cardio-respiratoires en préhospitalier] Marie-Claude Vézina MD, Claude A. Trépanier MD FRCPC, Pierre C. Nicole MD FRCPC, Martin R. Lessard MD FRCPC Purpose: The Esophageal-Tracheal Combitube® (Combitube) CAN J ANESTH 2007 / 54: 2 / pp 124–128 is widely used for the management of the airway during cardi- opulmonary resuscitation in the pre-hospital setting. Although serious complications have been reported with the Combitube, there is a paucity of data relative to the frequency and nature Objectif : Le Esophageal-Tracheal Combitube® (Combitube) est of such complications. The objective of this retrospective study couramment utilisé pour assurer le contrôle des voies aériennes lors was to determine the incidence and the nature of complications de situations d’arrêt cardio-respiratoire en préhospitalier. Bien que associated to the Combitube in the pre-hospital setting. des complications graves reliées à l’utilisation du Combitube aient Methods: Since 1993, in the Quebec City Health Region, the été rapportées, leur incidence réelle est mal connue. L’objectif de basic life support treatment algorithm for emergency medical cette étude rétrospective était d’estimer l’incidence et la nature technicians has included the use of a Combitube as the primary des complications associées à l’utilisation du Combitube en pré- airway device for management of all patients presenting with hospitalier. cardiac or respiratory arrest. The database of the emergency Méthode : Depuis 1993, le protocole de prise en charge préhospi- coordination services was searched for the period between talière de l’Agence régionale de santé de Québec inclut l’insertion 1993 and 2003 (2,981 patients). -

Overdose Or Toxic Ingestion

North Carolina College of Emergency Physicians Standards for EMS Medications and Skills Use B. The baseline medications and skills required in all systems and Specialty Care Transport Programs) with EMS personnel credentialed at the specified level. S. The equipment required in all Specialty Care Transport Programs. All Air Medical Specialty Care Transport Programs and dedicated Neonatal Transport Programs are required to carry and maintain equipment and medications specific to each mission, as defined by medical control and OEMS approved protocols. O. These medications and skills are optional. This medication list is based on the medications which are used in the NCCEP Protocol documents. This list does not include all of the medications which are approved for use by the NC Medical Board. The NC Medical Board Medication and Skills Formulary can be found online at www.NCEMS.org under the OEMS regulations section of the website. EMS Medications MR EMT EMT-I EMT-P Acetaminophen O O B9 B Adenosine B Beta-agonists (Albuterol, Levalbuterol, etc.) B6 B B Amiodarone B1 Anti-emetic preparations B Aspirin B6 B B Atropine O1 O1 O1 B Beta Blockers (Metoprolol, etc.) B8 Benzodiazepine (Diazepam, Midazolam, etc.) B2 Calcium Channel Blockers (Diltiazem, etc) B8 Calcium chloride/gluconate B Charcoal O O O Crystalloid solutions (Normal Saline, etc) B B Diphenhydramine O2 B B Dobutamine S, O Dopamine B Epinephrine B5,6 B5,6 B B Etomidate O Furosemide O Glucagon B B Glucose solutions B B Haloperidol O Histamine 2 Blockers (Ranitidine, Cimetidine) O O Ipratropium -

Combitube Insertion in the Situation of Acute Airway Obstruction After Extubation in Patients Underwent Two-Jaw Surgery

pISSN 2383-9309❚eISSN 2383-9317 Case Report J Dent Anesth Pain Med 2015;15(4):235-239❚http://dx.doi.org/10.17245/jdapm.2015.15.4.235 Combitube insertion in the situation of acute airway obstruction after extubation in patients underwent two-jaw surgery Yoon Ji Choi1, Sookyung Park2, Seong-In Chi2, Hyun Jeong Kim2,3, Kwang-Suk Seo2,3 1Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, Seoul National University Bungdang Hospital, Seongnam, Korea 2Department of Dental Anesthesiology, Seoul National University Dental Hospital, Seoul, Korea 3Department of Dental Anesthesiology, Dental Research Institute, School of Dentistry, Seoul National University, Seoul, Korea The Combitube is an emergency airway-maintaining device, which can supply oxygen to dyspneic patients in emergency situations following two-jaw surgery. These patients experience difficulty in opening the mouth or have a partially obstructed airway caused by edema or hematoma in the oral cavity. As such, they cannot maintain the normal airway. The use of a Combitube may be favorable compared to the laryngeal mask airway because it is a thin and relatively resilient tube. A healthy 24-year-old man was dyspneic after extubation. Oxygen saturation fell below 90% despite untying the bimaxillary fixation and ambubagging. The opening of the mouth was narrow; thus, emergency airway maintenance was gained by insertion of a Combitube. The following day, a facial computer tomography revealed that the airway space narrowing was severe compared to its pre-operational state. After the swelling subsided, the patient was successfully extubated without complications. Key Words: Airway obstruction; Combitube; Extubation; Post-anesthesia complication, Two-jaw surgery. -

New Mexico Emergency Medical Services Guidelines Procedures

NEW MEXICO EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES GUIDELINES PROCEDURES FIRST RESPONDER EMT- BASIC EMT- INTERMEDIATE (EMT-I) EMT-PARAMEDIC Updated September 2018 TABLE OF CONTENTS Contents ACUPRESSURE ....................................................................................................................................... 1 AIRWAY MANAGEMENT ......................................................................................................................... 2 GENERAL GUIDELINES ...................................................................................................................... 2 OROPHARYNGEAL SUCTIONING ...................................................................................................... 3 ENDOTRACHEAL SUCTIONING ......................................................................................................... 4 OROPHARYNGEAL AIRWAY .............................................................................................................. 6 NASOPHARANGEAL AIRWAY ............................................................................................................ 7 COMBITUBE® ...................................................................................................................................... 8 LARYNGEAL and SUPRAGLOTTIC AIRWAY DEVICES ................................................................... 11 KING AIRWAY ................................................................................................................................................................ -

Michigan PROCEDURES EMERGENCY AIRWAY

Michigan PROCEDURES EMERGENCY AIRWAY September, 2019 Section 7-9 Emergency Airway Alias: Airway Management, Airway Intervention, Supraglottic Airway, Intubation, Cricothyroidotomy. Effective airway management and ventilation are important lifesaving interventions that all EMS providers must be able to perform. The approach to airway management should generally proceed in a stepwise fashion, from basic to advanced, since basic maneuvers can sustain life until an advanced airway can be established. Providers should use clinical judgment in conjunction with medical direction to determine which interventions are most appropriate for a particular patient. Indications for Airway Management and Ventilation 1. Airway Management a. Airway obstruction b. Need for positive pressure ventilation (see below) c. Airway protection, such as an unconscious patient without a gag reflex. d. Trauma patient with a Glasgow Coma Score of 8 or less. 2. Positive Pressure Ventilation a. Respiratory or cardiac arrest (including agonal respirations) b. Respiratory failure (inadequate respiratory rate/volume) Contraindications for Airway Management and Ventilation 1. Presence of a gag reflex may be a contraindication to some specific airway interventions. 2. Specific supraglottic airways may have contraindications due to caustic ingestion or known esophageal varices. MANAGEMENT OVERVIEW 1. In cases of foreign body airway obstruction, refer to Foreign Body Airway Obstruction section of this protocol. 2. CPAP (when available) should be considered for patients with severe respiratory distress that do not improve with supplemental oxygen administration in accordance with the CPAP/BiPAP Administration Procedure. 3. When the airway is not self-maintained, open the airway using basic maneuvers (chin lift or jaw thrust). Patients with a potential cervical spine injury should have a modified jaw thrust performed attempting to minimize neck flexion and extension. -

BASE HOSPITAL AIRWAY PROTOCOL INDEX Base Hospital

BASE HOSPITAL AIRWAY PROTOCOL INDEX Base Hospital 1. Airway Management Protocol 2. Auto Vent (ATV) 3. Combitube Protocol 4. CPAP 5. I-gel Protocol 6. King-LTS-D Protocol 7. Medicated Facilitated Intubation Created 1-15; 01-16; 09-16; 04-19, 06-2020; Reviewed 02/21 AIRWAY MANAGEMENT Base Hospital STANDARD OPERATIONAL GUIDANCE Purpose To define the indications and procedure for ventilation and oxygenation, for apnea, respiratory failure, inability to protect airway, or hypoxia Standard Operational Guidance (SOG) 1. These reference documents and Standard Operational Guidance protocols will be used: SAEMS Airway Management Procedure Protocol TMC Continuous Positive Airway Pressure (CPAP) SOG TMC Policy 18.01.17 (ETDLAD) TMC KING LTS-D SOG TMC Combitube SOG TMC ATV SOG Treatment Guidance 1. The ECMT should have situational awareness as there are many options for airway management. The prehospital provider should be ready to individualize treatment, as every case is different. Non-invasive management should be attempted using the SAEMS Airway Management Procedure prior to moving forward. 2. These guidelines assume the treating EMCT professional is skilled in the various procedures appropriate for their scope of practice. Advanced procedures should only be attempted if clinically indicated after less invasive measures fail or are futile to attempt. Individual cases may require modification of these protocols. Airway management decisions and actions should always be thoroughly documented in the patient care report. 3. Continuous Positive Airway Pressure has been shown to rapidly improve vital signs, gas exchange, reduce the work of breathing, decrease the sense of dyspnea, and decrease the need for endotracheal intubation in patients who suffer from shortness of breath from asthma, COPD, pulmonary edema, CHF, and pneumonia.