Bag-Valve Mask Ventilation” Page 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABCDE Approach

The ABCDE and SAMPLE History Approach Basic Emergency Care Course Objectives • List the hazards that must be considered when approaching an ill or injured person • List the elements to approaching an ill or injured person safely • List the components of the systematic ABCDE approach to emergency patients • Assess an airway • Explain when to use airway devices • Explain when advanced airway management is needed • Assess breathing • Explain when to assist breathing • Assess fluid status (circulation) • Provide appropriate fluid resuscitation • Describe the critical ABCDE actions • List the elements of a SAMPLE history • Perform a relevant SAMPLE history. Essential skills • Assessing ABCDE • Needle-decompression for tension • Cervical spine immobilization pneumothorax • • Full spine immobilization Three-sided dressing for chest wound • • Head-tilt and chin-life/jaw thrust Intravenous (IV) line placement • • Airway suctioning IV fluid resuscitation • • Management of choking Direct pressure/ deep wound packing for haemorrhage control • Recovery position • Tourniquet for haemorrhage control • Nasopharyngeal (NPA) and oropharyngeal • airway (OPA) placement Pelvic binding • • Bag-valve-mask ventilation Wound management • • Skin pinch test Fracture immobilization • • AVPU (alert, voice, pain, unresponsive) Snake bite management assessment • Glucose administration Why the ABCDE approach? • Approach every patient in a systematic way • Recognize life-threatening conditions early • DO most critical interventions first - fix problems before moving on -

Airway – Oropharyngeal: Insertion; Maintenance; Suction; Removal

Policies & Procedures Title: AIRWAY – OROPHARYNGEAL: INSERTION; MAINTENANCE; SUCTION; REMOVAL I.D. Number: 1159 Authorization Source: Nursing Date Revised: September 2014 [X] SHR Nursing Practice Committee Date Effective: October 2002 Date Reaffirmed: January 2016 Scope: SHR Acute, Parkridge Centre Any PRINTED version of this document is only accurate up to the date of printing 30-May-16. Saskatoon Health Region (SHR) cannot guarantee the currency or accuracy of any printed policy. Always refer to the Policies and Procedures site for the most current versions of documents in effect. SHR accepts no responsibility for use of this material by any person or organization not associated with SHR. No part of this document may be reproduced in any form for publication without permission of SHR. 1. PURPOSE 1.1 To safely and effectively use Oropharyngeal Airway (OPA). 2. POLICY 2.1 The Registered Nurse (RN), Registered Psychiatric Nurse (RPN), Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN), Graduate Nurse (GN), Graduate Psychiatric Nurse (GPN), Graduate Licensed Practical Nurse (GLPN) will insert, maintain, suction and remove an oropharyngeal airway (OPA). 2.2 The OPA may be inserted to establish and assist in maintaining a patent airway. 2.3 An OPA should only be used in patients with decreased level of consciousness or decreased gag reflex. 2.4 Patients with OPAs that have been inserted for airway protection should not be left unattended due to risk of aspiration if gag reflex returns unexpectedly. Page 1 of 4 Policies and Procedures: Airway – Oropharyngeal: Insertion; Maintenance; I.D. # 1159 Suction; Removal 3. PROCEDURE 3.1 Equipment: • Oropharyngeal airway of appropriate size • Tongue blade (optional) • Clean gloves • Optional: suction equipment, bag-valve-mask device 3.2 Estimate the appropriate size of airway by aligning the tube on the side of the patient’s face parallel to the teeth and choosing an airway that extends from the ear lobe to the corner of the mouth. -

Cricoid Pressure: Ritual Or Effective Measure?

R eview A rticle Singapore Med J 2012; 53(9) 620 Cricoid pressure: ritual or effective measure? Nivan Loganathan1, MB BCh BAO, Eugene Hern Choon Liu1, MD, FRCA ABSTRACT Cricoid pressure has been long used by clinicians to reduce the risk of aspiration during tracheal intubation. Historically, it is defined by Sellick as temporary occlusion of the upper end of the oesophagus by backward pressure of the cricoid cartilage against the bodies of the cervical vertebrae. The clinical relevance of cricoid pressure has been questioned despite its regular use in clinical practice. In this review, we address some of the controversies related to the use of cricoid pressure. Keywords: cricoid pressure, regurgitation Singapore Med J 2012; 53(9): 620–622 INTRODUCTION imaging showed that in 49% of patients in whom cricoid Cricoid pressure is a technique used worldwide to reduce pressure was applied, the oesophageal position was lateral to the risk of aspiration during tracheal intubation in sedated or the cricoid ring.(5) As oesophageal occlusion was thought to be anaesthetised patients. Cricoid pressure can be traced back to crucial, this study challenged the efficacy of cricoid pressure. the late 18th century when it was used to prevent gas inflation More recently, in magnetic resonance imaging studies, Rice et of the stomach during resuscitation from drowning.(1) Sellick al showed that cricoid pressure causes compression of the post- noted that cricoid pressure could both prevent regurgitation cricoid hypopharynx rather than the oesophagus itself. -

Title: Cricoid Pressure During Intubation: Review of Research and Survey of Nurse Anesthetists

Title: Cricoid Pressure During Intubation: Review of Research and Survey of Nurse Anesthetists Tania A. Lalli, BSN School of Nursing, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, Greensboro, NC, USA Michael Rieker, DNP School of Medicine, Nurse Anesthesia Program - Wake Forest School of Medicine, Winston Salem, NC, USA Donald D. Kautz, PhD Adult Health, School of Nursing, University of North Carolina Greensboro, Greensboro, NC, USA Session Title: Scientific Posters Session 2 Keywords: Aspiration, Cricoid pressure and Effectiveness References: Baskett, P.J.F., & Baskett, T.F. (2004). Brian sellick, cricoid pressure and the sellick manouevre. Resuscitation, 61(1). doi:10.1016/j.resuscitation.2004.03.001 Beavers, R.A., Moos, D.D., & Cuddeford, J.D. (2009). Analysis of the application of cricoid pressure: Implications for the clinician. The Journal of PeriAnesthesia Nursing, 24(2), 92-102. Black, S.J., Carson, E.M., & Doughty, A. (2012). How much and where: Assessment of Knowledge level of the application of cricoid pressure. The Journal of Emergency Nursing, 28(4), 370-374. Brimacombe, J.R., & Berry, A.M. (1997). Cricoid pressure. The Canadian Journal of Anesthesia, 44(4), 414-425. Engelhardt, T., & Webster, N.R. (1999). Pulmonary aspiration of gastric contents. The British Journal of Anesthesia, 83, 453-460. Ewart, L. (2007). The efficacy of cricoid pressure in preventing gastro-oesophageal reflux in rapid sequence induction of anaesthesia. The Journal of Preoperative Practice, 17(9), 432-436. Garrard, A., Campbell, A., Turley, A., & Hall J. (2004). The effect of mechanically-induced cricoid force on lower oesophageal sphincter pressure in anaesthetised patients. Anaesthesia, 59(5), 435-439. -

Rapid Sequence Induction Will Ross and Louise Ellard

Update in Anaesthesia Rapid sequence induction Will Ross and Louise Ellard Correspondence: [email protected] Originally published as Anaesthesia Tutorial of the Week 331, 24 May 2016, edited by Dr Luke Baitch Table 1. Common modifications of RSI technique in INTRODUCTION current practice Rapid sequence induction (RSI) is a method of achiev- Omitting the placement of an oesophageal tube articlesClinical overview ing rapid control of the airway whilst minimising Supine or ramped positioning the risk of regurgitation and aspiration of gastric Titrating the dose of induction agent to loss of contents. Intravenous induction of anaesthesia, with consciousness the application of cricoid pressure, is swiftly followed Summary by the placement of an endotracheal tube (ETT). Use of propofol, ketamine, midazolam or etomidate to Rapid sequence induction induce anaesthesia (RSI) is intended to reduce Performance of an RSI is a high priority in many the risk of aspiration by emergency situations when the airway is at risk, and Use of high-dose rocuronium as a neuromuscular blocking agent minimising the duration is usually an essential component of anaesthesia for of an unprotected airway. Omitting cricoid pressure emergency surgical interventions. RSI is required only Preparation and planning in patients with preserved airway reflexes. In arrested – including technique, or completely obtunded patients, an endotracheal tube medications, team member can usually be placed without the use of medications. CRICOID PRESSURE roles and contingencies -

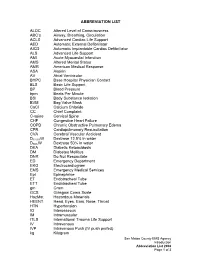

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC's Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Suppo

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC’s Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support AED Automatic External Defibrillator AICD Automatic Implantable Cardiac Defibrillator ALS Advanced Life Support AMI Acute Myocardial Infarction AMS Altered Mental Status AMR American Medical Response ASA Aspirin AV Atrial Ventricular BHPC Base Hospital Physician Contact BLS Basic Life Support BP Blood Pressure bpm Beats Per Minute BSI Body Substance Isolation BVM Bag Valve Mask CaCl Calcium Chloride CC Chief Complaint C-spine Cervical Spine CHF Congestive Heart Failure COPD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Edema CPR Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation CVA Cerebral Vascular Accident D12.5%W Dextrose 12.5% in water D50%W Dextrose 50% in water DKA Diabetic Ketoacidosis DM Diabetes Mellitus DNR Do Not Resuscitate ED Emergency Department EKG Electrocardiogram EMS Emergency Medical Services Epi Epinephrine ET Endotracheal Tube ETT Endotracheal Tube gm Gram GCS Glasgow Coma Scale HazMat Hazardous Materials HEENT Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Throat HTN Hypertension IO Interosseous IM Intramuscular ITLS International Trauma Life Support IV Intravenous IVP Intravenous Push (IV push prefed) kg Kilogram San Mateo County EMS Agency Introduction Abbreviation List 2008 Page 1 of 3 J Joule LOC Loss of Consciousness Max Maximum mcg Microgram meds Medication mEq Milliequivalent min Minute mg Milligram MI Myocardial Infarction mL Milliliter MVC Motor Vehicle Collision NPA Nasopharyngeal Airway NPO Nothing Per Mouth NS Normal Saline NT Nasal Tube NTG Nitroglycerine NS Normal Saline O2 Oxygen OB Obstetrical OD Overdose OPA Oropharyngeal Airway OPQRST Onset, Provoked, Quality, Region and Radiation, Severity, Time OTC Over the Counter PAC Premature Atrial Contraction PALS Pediatric Advanced Life Support PEA Pulseless Electrical Activity PHTLS Prehospital Trauma Life Support PID Pelvic Inflammatory Disease PO By Mouth Pt. -

Best Airway and Ventilation Strategy During CPR and After Resuscitation

Best airway and ventilation strategy during CPR and after resuscitation After cardiac arrest a combination of basic and advanced airway and ventilation techniques are used during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and after a return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). Current guidelines are based predominantly on evidence from observational studies and expert consensus; thus, the optimal combination of airway techniques and oxygen and ventilation targets during CPR and after ROSC is uncertain, according to a review article in the journal Critical Care. Current evidence supports a stepwise approach to airway management based on patient factors, rescuer skills and the stage of resuscitation. Observational data suggest that early lay-bystander compression-only CPR can improve survival after sudden cardiac arrest. Chest compressions are easy to learn and do for most rescuers and do not require special equipment. Studies show that lay rescuer compression-only CPR is better than no CPR. During CPR, airway interventions range from compression-only CPR with or without airway opening, mouth-to-mouth ventilation, mouth-to-mask ventilation, bag-mask ventilation (with or without an oropharyngeal airway) or advanced airways (supraglottic airways [SGAs] and tracheal intubation using direct or video laryngoscopy). On arrival of trained rescuers, bag-mask ventilation with supplemental oxygen is the most common initial approach and can be aided with an oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airway. During CPR, the bag-mask is used to give two breaths after every 30 compressions. A pre-specified per-protocol analysis reported a significantly higher survival to discharge among those who actually received conventional CPR (30:2) compared with those who received continuous compressions. -

The Golden Hour > How Time Shapes Airway Management > by Charlie Eisele,BS,NREMT-P

September 2008 The A supplement to JEMS (the Journal of Emergency Medical Services) Conscience of EMS JOURNAL OF EMERGENCY MEDICAL SERVICES Sponsored by Verathon Inc. ELSEVIER PUBLIC SAFETY The Perfect View How Video Laryngoscopy Is Changing the Face of Prehospital Airway Management A supplement to September 2008 JEMS, sponsored by Verathon Inc. 4 Foreword > To See or Not to See, That Is the Question > By A.J.Heightman,MPA,EMT-P 5 5 The Golden Hour > How Time Shapes Airway Management > By Charlie Eisele,BS,NREMT-P 9 The Video Laryngoscopy Movement > Can-Do Technology at Work > By John Allen Pacey,MD,FRCSc 11 ‘Grounded’ Care > Use of Video Laryngoscopy in a Ground 11 EMS System: Better for You, Better for Your Patients > By Marvin Wayne,MD,FACEP,FAAEM 14 Up in the Air > Video Laryngoscopy Holds Promise for In-Flight Intubation > By Lars P.Bjoernsen,MD,& M.Bruce Lindsay,MD 16 16 The Military Experience > The GlideScope Ranger Improves Visualization in the Combat Setting > By Michael R.Hawkins,MS,CRNA 19 Using Is Believing > Highlights from 72 Cases Involving Video Laryngoscopy at Martin County (Fla.) Fire Rescue > By David Zarker,EMT-P 21 Teaching the Airway > Designing Educational Programs for 21 Emergency Airway Management > By Michael F.Murphy,MD; Ron M.Walls,MD; & Robert C.Luten,MD COVER PHOTO KEVIN LINK Disclosure of Author Relationships: Authors have been asked to disclose any relationships they may have with commercial supporters of this supplement or with companies that may have relevance to the content of the supplement. Such disclosure at the end of each article is intended to provide readers with sufficient information to evaluate whether any material in the supplement has been influenced by the writer’s relationship(s) or financial interests with said companies. -

Cricoid Pressure Pendulum When Dr

Brandon Morshedi, MD, DPT The Cricoid Pressure Pendulum When Dr. Sellick first introduced the idea of “cricoid pressure” in 1961, he stated that "the maneuver consists of temporary occlusion of the upper end of the esophagus by backward pressure of cricoid cartilage against bodies of cervical vertebrae."[1] His published research, however, had some noted limitations. They were small, non- randomized, uncontrolled case series that were performed on patients undergoing induction with anesthesia. The patients were positioned "head down slightly with head turned" and there was no mention of the sequence of administration or dosing of the induction agent and paralytics that were used in the anesthesia.[1][2] Sellick also did not discuss the actual technique of cricoid pressure, including how much pressure to apply, and admitted that it was performed by untrained personnel. Despite these major limitations, this technique was rapidly and rather uncritically adopted by anesthetists all over the world.[2] Over the past two decades, many providers have questioned the utility of cricoid pressure and many studies have been published which further support or refute its efficacy. Specifically, the following is the evidence regarding the question of whether cricoid pressure does what it is suppose to do or not, whether it can make our management of the airway more difficult, and whether or not we should be using it. Does Cricoid Pressure Occlude the Esophagus and Prevent Regurgitation? According to one author, crucial to the theorized effectiveness of cricoid pressure is the idea that the cricoid cartilage, esophagus, and vertebral bodies are all perfectly aligned in the axial plane.[2][3] In a retrospective review of 51 cervical CT scans and a prospective analysis of 22 cervical MRI scans, there was some degree of lateral displacement of the esophagus relative to the midline in 49% and 53%, respectively, even without cricoid pressure. -

Paramedic Airway Management Course

Pierce County EMS Paramedic Airway Course 2nd Edition September 2012 Pierce County EMS Paramedic Airway Management Course Table of Contents: Acknowledgements ............................................................................................ 3 Course Purpose and Description ..................................................................... 4 Background ........................................................................................................ 5 Assessing the Need for Emergency Airway Management ............................. 6 Effective Use of the Bag-Valve Mask ............................................................... 7 Endotracheal Intubation—Preparing for First Pass Success ........................ 8 RSI & Endotracheal Intubation ....................................................................... 11 Confirming, Securing and Monitoring Airway Placement ............................ 15 Use of Alternative “Rescue Airways” ............................................................ 16 Surgical Airways .............................................................................................. 17 Emergency Airway Management in Special Populations: ........................... 18 Pediatric Patients Geriatric Patients Trauma Patients Bariatric Patients Pregnant Patients Ten Tips for Best Practices in Emergency Airway Management ................ 21 Airway Performance Documentation and CQI Analysis ............................... 22 Conclusion ...................................................................................................... -

Success Rate of Resuscitation After Out-Of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest

Commentary Success rate of resuscitation after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest Anthony MH Ho1, FRCPC, FCCP, Glenio B Mizubuti1 *, MSc, MD, Adrienne K Ho2, MB, BS, Song Wan3, MD, FRCS, Devin Sydor1, MD, FRCPC, David C Chung4, MD, FRCPC 1Department of Anesthesiology and Perioperative Medicine, Queen’s University, Canada 2Department of Oncology, The Christie NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester, United Kingdom 3Division of Cardiac Surgery, Department of Surgery, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong 4Department of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong * Corresponding author: [email protected] Hong Kong Med J 2019;25:254–6 https://doi.org/10.12809/hkmj187596 A recent study in Hong Kong documented the low lack of which is linked to poor outcomes.5 However, success rate of resuscitation after adult out-of-hospital because 60% of adult and 38% of paediatric OHCAs cardiac arrest (OHCA). Survival to hospital discharge in Hong Kong are unwitnessed,1,4 these first few with good neurological outcome was 1.5%.1 A median minutes of sufficient oxygen in the blood (for sudden delay of 12 minutes for defibrillation was one factor arrest of cardiac origin) may have already elapsed. that contributed to poor outcomes.1 In ventricular This raises the question of whether a one-size-fits- fibrillation or pulseless ventricular tachycardia, every all bystander CPR with no breathing component minute without defibrillation drastically reduces is advisable. It is not surprising that the rates of the chance of successful resuscitation.2 To partially survival with good neurological outcomes are mitigate the delayed arrival of trained personnel to low. -

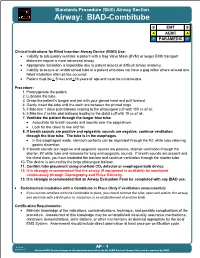

EMS Patient Care Procedure Documents for NC EMS Systems

Standards Procedure (Skill) Airway Section Airway: BIAD-Combitube B EMT B A AEMT A P PARAMEDIC P Clinical Indications for Blind Insertion Airway Device (BIAD) Use: Inability to adequately ventilate a patient with a Bag Valve Mask (BVM) or longer EMS transport distances require a more advanced airway. Appropriate intubation is impossible due to patient access or difficult airway anatomy. Inability to secure an endotracheal tube in a patient who does not have a gag reflex where at least one failed intubation attempt has occurred. Patient must be > 5 feet and >16 years of age and must be unconscious. Procedure: 1. Preoxygenate the patient. 2. Lubricate the tube. 3. Grasp the patient s tongue and jaw with your gloved hand and pull forward. 4. Gently insert the tube until the teeth are between the printed rings. 5. Inflate line 1 (blue pilot balloon) leading to the pharyngeal cuff with 100 cc of air. 6. Inflate line 2 (white pilot balloon) leading to the distal cuff with 15 cc of air. 7. Ventilate the patient through the longer blue tube. Auscultate for breath sounds and sounds over the epigastrium. Look for the chest to rise and fall. 8. If breath sounds are positive and epigastric sounds are negative, continue ventilation through the blue tube. The tube is in the esophagus. In the esophageal mode, stomach contents can be aspirated through the #2, white tube relieving gastric distention. 9. If breath sounds are negative and epigastric sounds are positive, attempt ventilation through the shorter, #2 white tube and reassess for lung and epigastric sounds.