The Golden Hour > How Time Shapes Airway Management > by Charlie Eisele,BS,NREMT-P

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ABCDE Approach

The ABCDE and SAMPLE History Approach Basic Emergency Care Course Objectives • List the hazards that must be considered when approaching an ill or injured person • List the elements to approaching an ill or injured person safely • List the components of the systematic ABCDE approach to emergency patients • Assess an airway • Explain when to use airway devices • Explain when advanced airway management is needed • Assess breathing • Explain when to assist breathing • Assess fluid status (circulation) • Provide appropriate fluid resuscitation • Describe the critical ABCDE actions • List the elements of a SAMPLE history • Perform a relevant SAMPLE history. Essential skills • Assessing ABCDE • Needle-decompression for tension • Cervical spine immobilization pneumothorax • • Full spine immobilization Three-sided dressing for chest wound • • Head-tilt and chin-life/jaw thrust Intravenous (IV) line placement • • Airway suctioning IV fluid resuscitation • • Management of choking Direct pressure/ deep wound packing for haemorrhage control • Recovery position • Tourniquet for haemorrhage control • Nasopharyngeal (NPA) and oropharyngeal • airway (OPA) placement Pelvic binding • • Bag-valve-mask ventilation Wound management • • Skin pinch test Fracture immobilization • • AVPU (alert, voice, pain, unresponsive) Snake bite management assessment • Glucose administration Why the ABCDE approach? • Approach every patient in a systematic way • Recognize life-threatening conditions early • DO most critical interventions first - fix problems before moving on -

Airway – Oropharyngeal: Insertion; Maintenance; Suction; Removal

Policies & Procedures Title: AIRWAY – OROPHARYNGEAL: INSERTION; MAINTENANCE; SUCTION; REMOVAL I.D. Number: 1159 Authorization Source: Nursing Date Revised: September 2014 [X] SHR Nursing Practice Committee Date Effective: October 2002 Date Reaffirmed: January 2016 Scope: SHR Acute, Parkridge Centre Any PRINTED version of this document is only accurate up to the date of printing 30-May-16. Saskatoon Health Region (SHR) cannot guarantee the currency or accuracy of any printed policy. Always refer to the Policies and Procedures site for the most current versions of documents in effect. SHR accepts no responsibility for use of this material by any person or organization not associated with SHR. No part of this document may be reproduced in any form for publication without permission of SHR. 1. PURPOSE 1.1 To safely and effectively use Oropharyngeal Airway (OPA). 2. POLICY 2.1 The Registered Nurse (RN), Registered Psychiatric Nurse (RPN), Licensed Practical Nurse (LPN), Graduate Nurse (GN), Graduate Psychiatric Nurse (GPN), Graduate Licensed Practical Nurse (GLPN) will insert, maintain, suction and remove an oropharyngeal airway (OPA). 2.2 The OPA may be inserted to establish and assist in maintaining a patent airway. 2.3 An OPA should only be used in patients with decreased level of consciousness or decreased gag reflex. 2.4 Patients with OPAs that have been inserted for airway protection should not be left unattended due to risk of aspiration if gag reflex returns unexpectedly. Page 1 of 4 Policies and Procedures: Airway – Oropharyngeal: Insertion; Maintenance; I.D. # 1159 Suction; Removal 3. PROCEDURE 3.1 Equipment: • Oropharyngeal airway of appropriate size • Tongue blade (optional) • Clean gloves • Optional: suction equipment, bag-valve-mask device 3.2 Estimate the appropriate size of airway by aligning the tube on the side of the patient’s face parallel to the teeth and choosing an airway that extends from the ear lobe to the corner of the mouth. -

The Golden Hour of Trauma

Lecture 4 Feb 27, 2018 THE GOLDEN HOUR OF TRAUMA DAVID KALB, MD MERCY HOSPITAL, COON RAPIDS, MN DR. R ADAMS COWLEY • July 25, 1917 – October 27,1991 • American surgeon • Pioneer in emergency medicine and trauma care • “Father of Trauma Medicine” • Founder of U.S’s first trauma center at U of MD, 1958 • Leader in use of helicopters for med evac of civilians, from 1969 • Founded the nation’s first statewide EMS system in 1972 ©AllinaHealthSystem Lecture 4 Feb 27, 2018 DR. R ADAMS COWLEY GOLDEN HOUR • Coined by Dr. Cowley • “There is a golden hour between life and death. If you are critically injured you have less than 60 minutes to survive. You might not die right then; it may be three days or two weeks later – but something has happened to your body that is irreparable.” (from U of MD website) • “the first hour after injury will largely determine a critically-injured person’s chances for survival” (MD State Medical Journal 1975) ©AllinaHealthSystem Lecture 4 Feb 27, 2018 GOLDEN HOUR GOLDEN HOUR ©AllinaHealthSystem Lecture 4 Feb 27, 2018 •What does the data show?? EVIDENCE IN FAVOR OF THE GOLDEN HOUR • 1993 Journal of Trauma Sampalis et al • Total prehospital time over 60 minutes was associated with significant increase in odds of mortality • 1999 Journal of Trauma Sampalis et al • Reduced prehospital time associated with reduced odds of dying • When outcomes controlled for • Severity of injury • Age of population ©AllinaHealthSystem Lecture 4 Feb 27, 2018 EVIDENCE IN FAVOR OF THE GOLDEN HOUR • Acad Emerg Med 2002 Blackwell et al • EMS response -

Strategies to Support the COVID-19 Response in Lmics a Virtual Seminar Series Screening, Triage and Patient Flow

Strategies to support the COVID-19 response in LMICs A virtual seminar series Screening, Triage and Patient Flow Bhakti Hansoti, MBChB, MPH, PhD - Associate Professor in Emergency Medicine, Johns Hopkins University OBJECTIVES 1. Clinical Features 2. Preparing the Department 3. Initial Management 4. Other Management Considerations 5. Summary Clinical Features Severity • Most people with COVID-19 develop mild or uncomplicated illness • Approximately 14% develop severe disease requiring hospitalization and oxygen support • 5% require admission to an intensive care unit • In severe cases, COVID-19 can be complicated by • Acute respiratory disease syndrome (ARDS) • Sepsis and septic shock • Multiorgan failure, including acute kidney injury and cardiac injury. Preparing the Department Elements to be assessed have been divided into the following areas: • Establishment of a core team and key internal and external contact points • Human, material and facility capacity • Communication and data protection • Hand hygiene, personal protective equipment (PPE), and waste management • Triage, first contact and prioritization • Patient placement, moving of the patients in the facility, and visitor access • Environmental cleaning https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/checklist- hospitals-preparing-reception-and-care-coronavirus-2019-covid-19 Split flow Protecting Yourself These videos can help with PPE donning and doffing technique: • Donning and doffing PPE https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I94l IH8xXg8 • Recommended PPE during care https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oPL -

High Performance CPR Update

High Performance CPR Update Page | 1 Final Revision 8/8/2012 As part of our ongoing Quality Assurance in Cardiac Arrest incidents, Skagit County EMS under the direction of Dr. Don Slack, MPD is making changes to the way that ALS and BLS providers perform CPR. Overview: CPR quality has a dramatic impact on pt survival when done according to these guidelines. Minimal breaks in compressions, full chest recoil, adequate compression depth and adequate compression rate are all components of CPR that an increase survival from sudden cardiac arrest. Together these components go together to create High Performance CPR (HP CPR). Roles: As a rule for the unconscious, unresponsive, pulseless patient the FIRST person to the patient starts compressions. SECOND person does defibrillation (If there are only 2 responders to begin with, ventilations should begin after the rhythm analysis and shock if indicated). THIRD person should start ventilating the patient, placing a King Airway as soon as is practical. A timekeeper needs to be assigned to ensure high quality CPR, minimal interruption and help track the ALS interventions. Principles of HP CPR 1. EMT’s own CPR!! 2. Minimize interruption in CPR at all times, use a timekeeper 3. Ensure proper depth of compressions (>2 inches) 4. Ensure full chest recoil/decompression 5. Ensure proper chest compression rate (100-120/min) 6. Rotate compressors at least every 2 minutes 7. Do not interrupt compressions to ventilate patient, even if an advanced airway is not placed 8. Hands off the chest only during analysis and shock delivery, hover hands over chest during shock delivery and be ready to resume compressions 9. -

Small Adult CPR-2 Bag with Litesaver Manometer Brochure

ORDERING INFORMATION Your Need ... Our Innovation® O Manometer 2 Detector 2 AerosolTubing Reservoir Infant Cushion Mask Expandable Large Bore Color-Coded Mask PEEP w/Filter StatCO Manometer LiteSaverTiming Light with CPR (Synthetic Rubber) CPR-2 (PVC) Light Blue Oxygen Bag Reservoir (22mm) Adult Cushion Mask SmallAdult Cushion Mask with Flange #3 Pediatric Cushion Mask Child Cushion Mask PEEP Valve Pop-Off Dark Blue Oxygen Reservoir 0-60 cm H PART # OTHER #10-56402 X X X X X X #10-56403 X X X X #10-56404 X X X X X #10-56411 X X X X #10-56412 X X X X X #10-56423 X X X X X X #10-56424 X X X X X X CPR-2 Small Adult Bag with Manometer #10-56432 X X X X X #10-56435 X X X X X X X #10-56437 X X X X #10-56438 X X X X X #10-56440 X X X X #10-58500 X X X X #10-58501 X X X X X #10-58502 X X X X X #10-58503 X X X X X X #10-58506 X X X X X X #10-58507 X X X X X #10-58509 X X X X X #10-58512 X X X X X X X #10-55901 X X X #10-55904 X X X #10-55907 X X X #10-55909 X X X X #10-55910 X X X X #10-55912 X X X #10-55913 X X X X X X No lock clip #10-55915 X X X X X #10-55916 X X X #10-55917 X X X X X #10-55918 X X X X X X #10-55922 X X X X X X X #10-55923 X X X X #10-55924 X X X X X #10-55928 X X X #10-58400 X X X X #10-55365 LiteSaver Manometer Assy 20/Box 0-60 cm H2O, Adult Frequency 10 BPM #10-55366 LiteSaver Manometer Assy 20/Box Assembly 0-60 cm H2O In-Line Tee Right Orientation, Adult Frequency 10 BPM #10-55367 LiteSaver Manometer Assy 20/Box Assembly 0-60 cm H2O In-Line Tee Left Orientation, Adult Frequency 10 BPM = CPR-2 Small Adult Bags *References Can EMS Providers Provide Appropriate Tidal Volumes in a Simulated Adult-sized Patient with a Pediatric-sized Bag-Valve-Mask? Journal Pre-hospital Emergency Care, Volume 21, 2017, Issue 1, Jeffery Siegler, MD, EMT-P, Melissa Kroll, MD, Susan Wojcik, PhD, ATC & Hawnwan Philip May, MD Avoid Airway Catastrophes on the Extremes of Minute Ventilation, Acepnow.com, January 20, 2015, Richard M. -

Ischemic Time in Patients Treated with Primary Angioplasty

Journal of the American College of Cardiology Vol. 54, No. 23, 2009 © 2009 by the American College of Cardiology Foundation ISSN 0735-1097/09/$36.00 Published by Elsevier Inc. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2009.08.023 et al. (1). De Luca et al. (3) also reported on the time EDITORIAL COMMENT dependence of survival with relation to ischemic time in patients treated with primary angioplasty. The infarct size curve in Figure 1A in Francone et al. (1) was very Ischemic Time similar to the curve reported by De Luca et al. (3)in terms of rate of mortality. With the paper by Francone et The New Gold Standard al. (1), we now have hard physiologic evidence that for ST-Segment Elevation ischemic times Ͼ90 min result in relatively little myo- Myocardial Infarction Care* cardial salvage. As we begin to consider other treatment strategies that could potentially reduce ischemic times, we must also Richard W. Smalling, MD, PHD consider whether there are patient subsets that should Houston, Texas have the most aggressive therapy, namely “high-risk patients.” De Luca et al. (4) found that survival was inversely proportional to ischemic time in high-risk patients but was not correlated with ischemic times in In this issue of the Journal, Francone et al. (1) report an low-risk patients. Additionally, in patients with patent analysis of the relationship between time from the onset infarct-related arteries on initial angiography, there was a of symptoms to reperfusion (ischemic time) in ST- low mortality rate, which was not related to ischemic segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) pa- time. -

Capnography (ILS/ALS)

Capnography (ILS/ALS) Clinical Indications: 1. Capnography shall be used as soon as possible in conjunction with any airway management adjunct, including endotracheal, Blind Insertion Airway Devices (BIAD) or Bag Valve Mask (BVM). 2. Capnography should also be used on all patients treated with CPAP or epinephrine for respiratory distress. 3. Acute respiratory distress. 4. Assisted ventilations. 5. Sustained altered mental status. Procedure: 1. Attach capnography sensor to the BIAD, endotracheal tube, or oxygen delivery device. 2. Note CO2 level and waveform changes. These will be documented on each respiratory failure, cardiac arrest, or respiratory distress patient. 3. The capnometer shall remain in place with the airway and be monitored throughout the prehospital care and transport. 4. Any loss of CO2 detection or waveform indicates an airway problem and should be documented. 5. The capnogram should be monitored as procedures are performed to verify or correct the airway problem. 6. Document the procedure and results on/with the Patient Care Report (PCR) and the Airway Evaluation Form. 7. In all patients with a pulse, an ETCO2 >20 is anticipated. In the post-resuscitation patient, no effort should be made to lower ETCO2 by modification of the ventilatory rate. Further, in post- resuscitation patients without evidence of ongoing, severe bronchospasm, ventilatory rate should never be < 6 breaths per minute. 8. In the pulseless patient, and ETCO2 waveform with an ETCO2 value >10 may be utilized to confirm the adequacy of an airway to include BVM and advanced devices when Sp02 will not register. Critical Comment: • When CO2 is NOT detected, three factors must be quickly assessed : 1. -

Lights and Siren Use by Emergency Medical Services (EMS): Above All Do No Harm

U. S. Department of Transportation National Highway Traffic Safety Administration Office of Emergency Medical Services (EMS) Lights and Siren Use by Emergency Medical Services (EMS): Above All Do No Harm Author: Douglas F. Kupas, MD, EMT-P, FAEMS, FACEP Submitted by Maryn Consulting, Inc. For NHTSA Contract DTNH22-14-F-00579 About the Author Dr. Douglas Kupas is an EMS physician and emergency physician, practicing at a tertiary care medical center that is a Level I adult trauma center and Level II pediatric trauma center. He has been an EMS provider for over 35 years, providing medical care as a paramedic with both volunteer and paid third service EMS agencies. His career academic interests include EMS patient and provider safety, emergency airway management, and cardiac arrest care. He is active with the National Association of EMS Physicians (former chair of Rural EMS, Standards and Practice, and Mobile Integrated Healthcare committees) and with the National Association of State EMS Officials (former chair of the Medical Directors Council). He is a professor of emergency medicine and is the Commonwealth EMS Medical Director for the Pennsylvania Department of Health. Disclosures The author has no financial conflict of interest with any company or organization related to the topics within this report. The author serves as an unpaid member of the Institutional Research Review Committee of the International Academy of Emergency Dispatch, Salt Lake City, UT. The author is employed as an emergency physician and EMS physician by Geisinger Health System, Danville, PA. The author is employed part-time as the Commonwealth EMS Medical Director by the Pennsylvania Department of Health, Bureau of EMS, Harrisburg, PA. -

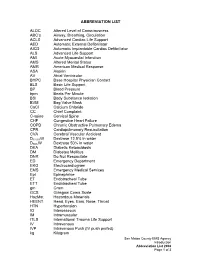

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC's Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Suppo

ABBREVIATION LIST ALOC Altered Level of Consciousness ABC’s Airway, Breathing, Circulation ACLS Advanced Cardiac Life Support AED Automatic External Defibrillator AICD Automatic Implantable Cardiac Defibrillator ALS Advanced Life Support AMI Acute Myocardial Infarction AMS Altered Mental Status AMR American Medical Response ASA Aspirin AV Atrial Ventricular BHPC Base Hospital Physician Contact BLS Basic Life Support BP Blood Pressure bpm Beats Per Minute BSI Body Substance Isolation BVM Bag Valve Mask CaCl Calcium Chloride CC Chief Complaint C-spine Cervical Spine CHF Congestive Heart Failure COPD Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Edema CPR Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation CVA Cerebral Vascular Accident D12.5%W Dextrose 12.5% in water D50%W Dextrose 50% in water DKA Diabetic Ketoacidosis DM Diabetes Mellitus DNR Do Not Resuscitate ED Emergency Department EKG Electrocardiogram EMS Emergency Medical Services Epi Epinephrine ET Endotracheal Tube ETT Endotracheal Tube gm Gram GCS Glasgow Coma Scale HazMat Hazardous Materials HEENT Head, Eyes, Ears, Nose, Throat HTN Hypertension IO Interosseous IM Intramuscular ITLS International Trauma Life Support IV Intravenous IVP Intravenous Push (IV push prefed) kg Kilogram San Mateo County EMS Agency Introduction Abbreviation List 2008 Page 1 of 3 J Joule LOC Loss of Consciousness Max Maximum mcg Microgram meds Medication mEq Milliequivalent min Minute mg Milligram MI Myocardial Infarction mL Milliliter MVC Motor Vehicle Collision NPA Nasopharyngeal Airway NPO Nothing Per Mouth NS Normal Saline NT Nasal Tube NTG Nitroglycerine NS Normal Saline O2 Oxygen OB Obstetrical OD Overdose OPA Oropharyngeal Airway OPQRST Onset, Provoked, Quality, Region and Radiation, Severity, Time OTC Over the Counter PAC Premature Atrial Contraction PALS Pediatric Advanced Life Support PEA Pulseless Electrical Activity PHTLS Prehospital Trauma Life Support PID Pelvic Inflammatory Disease PO By Mouth Pt. -

Information on Defibrillation and Ventilation with the LUCAS® Chest Compression System

® LUCAS CHEST COMPRESSION SYSTEM Information on Defibrillation and Ventilation with the LUCAS® Chest Compression System The goal when using the LUCAS device is to provide effective, After Defibrillation consistent, and uninterrupted chest compressions. When an After the shock is delivered it is important to verify the position of the interruption to chest compressions occurs, the patient’s coronary suction cup to see it has not moved out of place. This is easier to do perfusion pressure (CPP) drops rapidly. CPP is the measure of the if an ink marker line was marked where the suction cup was originally pressure that drives blood flow through the coronary arteries to the positioned on the patient. Readjust as necessary. heart muscle. The heart normally maintains a CPP of 60 millimeters of mercury (mmHg) or more. During cardiac arrest, the CPP drops dramatically, threatening the heart muscle’s blood supply. As it can take Oxygenation with Ventilation some time to build up CPP again, interruptions to chest compressions should be minimized. To supply adequate concentrations of oxygen in the blood, ensure the patient is properly ventilated. Ventilations should be provided in The current American Heart Association Guidelines emphasize conjunction with mechanical chest compressions. Interruptions to 1 minimizing interruptions when delivering high quality CPR: chest compressions should be minimized to maintain the level of • Minimize pre- and post-shock pauses (class I), oxygen delivered to tissues. During the first few minutes of sudden cardiac arrest, chest compressions to improve blood flow have been • Pause compressions for less than 10 seconds when delivering two shown to be more important than ventilations because oxygen blood breaths (class IIa), levels remain high initially.4 • Maximize the time with chest compressions (class IIb). -

Best Airway and Ventilation Strategy During CPR and After Resuscitation

Best airway and ventilation strategy during CPR and after resuscitation After cardiac arrest a combination of basic and advanced airway and ventilation techniques are used during cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and after a return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). Current guidelines are based predominantly on evidence from observational studies and expert consensus; thus, the optimal combination of airway techniques and oxygen and ventilation targets during CPR and after ROSC is uncertain, according to a review article in the journal Critical Care. Current evidence supports a stepwise approach to airway management based on patient factors, rescuer skills and the stage of resuscitation. Observational data suggest that early lay-bystander compression-only CPR can improve survival after sudden cardiac arrest. Chest compressions are easy to learn and do for most rescuers and do not require special equipment. Studies show that lay rescuer compression-only CPR is better than no CPR. During CPR, airway interventions range from compression-only CPR with or without airway opening, mouth-to-mouth ventilation, mouth-to-mask ventilation, bag-mask ventilation (with or without an oropharyngeal airway) or advanced airways (supraglottic airways [SGAs] and tracheal intubation using direct or video laryngoscopy). On arrival of trained rescuers, bag-mask ventilation with supplemental oxygen is the most common initial approach and can be aided with an oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airway. During CPR, the bag-mask is used to give two breaths after every 30 compressions. A pre-specified per-protocol analysis reported a significantly higher survival to discharge among those who actually received conventional CPR (30:2) compared with those who received continuous compressions.