Beyond 'The Soldier and the State'

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Waltz's Theory of Theory

WALTZ’S THEORY OF THEORY 201 Waltz’s Theory of Theory Ole Wæver Abstract Waltz’s 1979 book, Theory of International Politics, is the most infl uential in the history of the discipline. It worked its effects to a large extent through raising the bar for what counted as theoretical work, in effect reshaping not only realism but rivals like liberalism and refl ectivism. Yet, ironically, there has been little attention paid to Waltz’s very explicit and original arguments about the nature of theory. This article explores and explicates Waltz’s theory of theory. Central attention is paid to his defi nition of theory as ‘a picture, mentally formed’ and to the radical anti-empiricism and anti-positivism of his position. Followers and critics alike have treated Waltzian neorealism as if it was at bottom a formal proposition about cause–effect relations. The extreme case of Waltz being so victorious in the discipline, and yet being so consistently misinterpreted on the question of theory, shows the power of a dominant philosophy of science in US IR, and thus the challenge facing any ambitious theorising. The article suggests a possible movement of fronts away from the ‘fourth debate’ between rationalism and refl ectivism towards one of theory against empiricism. To help this new agenda, the article introduces a key literature from the philosophy of science about the structure of theory, and particularly about the way even natural science uses theory very differently from the way IR’s mainstream thinks it does – and much more like the way Waltz wants his theory to be used. -

Analyzing Change in International Politics: the New Institutionalism and the Interpretative Approach

Analyzing Change in International Politics: The New Institutionalism and the Interpretative Approach - Guest Lecture - Peter J. Katzenstein* 90/10 This discussion paper was presented as a guest lecture at the MPI für Gesellschaftsforschung, Köln, on April 5, 1990 Max-Planck-Institut für Gesellschaftsforschung Lothringer Str. 78 D-5000 Köln 1 Federal Republic of Germany MPIFG Discussion Paper 90/10 Telephone 0221/ 336050 ISSN 0933-5668 Fax 0221/ 3360555 November 1990 * Prof. Peter J. Katzenstein, Cornell University, Department of Government, McGraw Hall, Ithaca, N.Y. 14853, USA 2 MPIFG Discussion Paper 90/10 Abstract This paper argues that realism misinterprets change in the international system. Realism conceives of states as actors and international regimes as variables that affect national strategies. Alternatively, we can think of states as structures and regimes as part of the overall context in which interests are defined. States conceived as structures offer rich insights into the causes and consequences of international politics. And regimes conceived as a context in which interests are defined offer a broad perspective of the interaction between norms and interests in international politics. The paper concludes by suggesting that it may be time to forego an exclusive reliance on the Euro-centric, Western state system for the derivation of analytical categories. Instead we may benefit also from studying the historical experi- ence of Asian empires while developing analytical categories which may be useful for the analysis of current international developments. ***** In diesem Aufsatz wird argumentiert, daß der "realistische" Ansatz außenpo- litischer Theorie Wandel im internationalen System fehlinterpretiere. Dieser versteht Staaten als Akteure und internationale Regime als Variablen, die nationale Strategien beeinflussen. -

Ed 393 216 Author Title Report No Pub Date Available From

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 393 216 EA 027 482 AUTHOR Scribner, Jay D., Ed.; Layton, Donald H., Ed. TITLE The Study of Educational Politics. 1994 Commemorative Yearbook of the Politics of Education Association (1969-1994). Education Policy Perspectives Series. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7507-0419-5 PUB DATE 95 NOTE 225p. AVAILABLE FROM Falmer Press, Taylor & Francis, Inc., 1900 Frost Road, Suite 101, Bristol, PA 19007 (paperback: ISBN-0-7507-0419-5; clothbound: ISBN-0-7507-0418-7). PUB TYPE Books (010) Collected Works General (020) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Educational Principles; Educational Sociology; Elementary Secondary Education; Feminism; Ideology; International Education; *Policy Analysis; *Policy Formation; Political Influences; *Politics of Education; Role of Education; Values ABSTRACT This book surveys major trends in the politics of education over the last 25 years. Chapters synthesize political and policy developments at local, national, and state levels in the United States, as well as in the international arena. The chapters examine the emerging micropolitics of education and policy-analysis, cultural, and feminist studies. The foreword is by Paul E. Peterson and the introduction by Jay D. Scribner and Donald H.Layton. Chapters include:(1) "Values: The 'What?' of the Politics of Education" (Robert T. Stout, Marilyn Tallerico, and Kent Paredes Scribner) ;(2) "The Politics of Education: From Political Science to Interdisciplinary Inquiry" (Kenneth K. Wong);(3) "The Crucible of Democracy: The Local Arena" (Laurence Iannaccone and Frank W.Lutz); (4) "State Policymaking and School Reform: Influences and Influentials" (Tim L. Mazzoni);(5) "Politics of Education at the Federal Level" (Gerald E. Sroufe) ;(6) "The International Arena: The Global Village" (Frances C. -

The London School of Economics and Political Science

The London School of Economics and Political Science Mercenaries and the State: How the hybridisation of the armed forces is changing the face of national security Caroline Varin A thesis submitted to the Department of International Relations of the London School of Economics for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, London, September 2012 ii Declaration I certify that the thesis I have presented for examination for the MPhil/PhD degree of the London School of Economics and Political Science is solely my own work other than where I have clearly indicated that it is the work of others (in which case the extent of any work carried out jointly by me and any other person is clearly identified in it). The copyright of this thesis rests with the author. Quotation from it is permitted, provided that full acknowledgement is made. This thesis may not be reproduced without my prior written consent. I warrant that this authorisation does not, to the best of my belief, infringe the rights of any third party. I declare that my thesis consists of <83,157> words. iii Abstract The military has been a symbol of nationhood and state control for the past two hundred years. As representatives of a society’s cultural values and political ambitions, the armed forces have traditionally been held within the confines of the modern state. Today, however, soldiers are expected to operate in the shadows of conflicts, drawing little attention to themselves and to their actions; they are physically and emotionally secluded from a civilian population whose governments, especially in the ‘West’, are proceeding to an unprecedented wave of demilitarisation and military budget cuts. -

FALL 1980 Published Quarterly by the American Political Science Association Volume XIII Number 4 Lbertyckssics

FALL 1980 Published quarterly by the American Political Science Association Volume XIII Number 4 LbertyCkssics E Pluribus Unum The Formation of the American Republic 1776-1790 By Forrest McDonald Having won their independence from England, ^^ the American colonies faced a new question '£ 'Pluribus ^'""§j| of paramount importance: Would this be politically one nation, or would it not? E Pluribus Unum is a provocative and spirited look at how that question came to be answered. "A fresh, vivid, and penetrating recreation of the crucial fourteen years in which a new nation was born "—New York limes Book Review. "Original and stimulating"—American Historical Review. "Highly readable and highly recommended" —Library Journal. "Will lead scholars to reassess some of their assumptions about the formative years of the American republic. As one of the most sprightly written brief accounts of this turbulent era it is also likely to gain a non-academic audience"—Annals of the American Academy. Hardcover $8.00, Paperback $3.50. We pay postage, but require prepayment, on orders from individuals. Please allow four to six weeks for delivery. To order this book, or for a copy of our catalog, write: LibertyPres.s/LibertyC/as.Hc.s 7440 North Shadeland, Dept. 718 Indianapolis, Indiana 46250 Fall 1980 Published quarterly by the American Political Science Association Volume XIII No. 4 407 PS Editorial Board Editor Chairman Walter E" Beach William S. Livingston Editorial Assistant University of Texas, Austin S. Sue Snook Kathleen Barber John Carroll University F. Chris Garcia University of New Mexico Dorothy Buckton James American University Earl Lewis Trinity University Naomi Lynn Kansas State University Published in February, May, August and November by The American Political Science Association 1 527 New Hampshire Avenue, N.W. -

Nlrcv20201.Pdf

1 2020 Nancy Lipton Rosenblum Senator Joseph S. Clark Professor of Ethics in Politics and Government, Emerita Harvard University Department of Government 1731 Cambridge St. Harvard University Cambridge, MA 02138 [email protected] Educational Background B.A., Radcliffe College, Social Studies, 1969 Ph.D., Harvard University Political Science, 1973 Teaching Positions Chair, Department of Government, Harvard University, 2004-2010 Senator Joseph S. Clark Professor of Ethics in Politics and Government, 2001 to 2016 Faculty Fellow, Safra Center for Ethics, Harvard University, 2003-4 Henry Merritt Wriston Professorship, Brown University, 1997- 2001 Chairperson, Political Science Department, Brown University, 1989-95 Professor, Brown University, 1980-2000 Liberal Arts Fellow, Harvard Law School, 1992-93 Fellow, Bunting Institute, Radcliffe College, 1988-89 Visiting Professor, Harvard University, Department of Government, Fall, 1985 Associate Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1977-80 Henry LaBarre Jayne Assistant Professor, Department of Government, Harvard University, 1973-77 Publications Books A Lot of People are Saying: The New Conspiracism and the Assault on Democracy”, with Russell Muirhead (Princeton University Press, 2019) 2 Good Neighbors: The Democracy of Everyday Life in America (Princeton University Press, 2016) On the Side of the Angels: An Appreciation of Parties and Partisanship (Princeton University Press, 2008) Membership and Morals: The Personal Uses of Pluralism in America (Princeton University -

Introduction to Political Science

Introduction to Political Science Professor Scott Williamson Fall 2021, Bocconi University e-mail: [email protected] Office hours: TBD Office: TBD Office room: TBD Class hours: TBD Class room: TBD Course Description What explains the rise of populism? How do authoritarian regimes hold onto power? Who opposes migration and why? When is the public more likely to hold political leaders accountable for poor governance? This course introduces the academic discipline of political science by exploring what its literatures have to say about these topics and others with substantive importance to global politics. We will read and discuss recent academic work utilizing a variety of methodological tools to answer these questions. In addition, the course is designed to help students navigate practical issues related to the effective conduct of political and social science research. We will review research practicalities ranging from choosing a research question to finding data and submitting articles to journals. Throughout the course, students will prepare a research proposal on a topic of their choice, which they will present to the class and submit in written format at the conclusion of the term. Course Objectives Throughout the course, students should expect: ▪ To develop knowledge about several major literatures in political science, gaining familiarity with ongoing debates and established findings. ▪ To acquire familiarity with a variety of primarily quantitative research methods used in political science and other social science disciplines. ▪ To develop understanding of how to consume and evaluate academic research, including how to recognize positive contributions, identify weaknesses, and provide constructive feedback in oral and written forms. -

Civil-Military Relations: a Comparative Analysis of the Role of the Military in the Political Transformation of Post-War Turkey and Greece: 1980-1995

CIVIL-MILITARY RELATIONS: A COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF THE ROLE OF THE MILITARY IN THE POLITICAL TRANSFORMATION OF POST-WAR TURKEY AND GREECE: 1980-1995 Dr. Gerassimos Karabelias Final Report submitted to North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) in June 1998 1 ABSTRACT This report attempts to determine the evolution of civil-military relations in Turkey and Greece during the 1980-1995 period through an examination of the role of the military in the political transformation of both countries. Since the mid-1970s and especially after the Fall of the Berlin Wall, the struggle for spreading the winds of democracy around the globe has been the goal of all western states and particularly the United States of America. However, taking into consideration the volatility in the Balkans and in Central Asia, the military institution of Turkey and Greece which gave the impression that it withdrew in the barracks after their last intervention in 1980-83 and 1967-74 respectively, could easily be forced or even tempted to assume a greater responsibility in the conduct of each country’s domestic and foreign affairs. Only through a better understanding of its role during the 1980-95 period, we would be able to determine the feasibility of such scenarios. Using a multi-factorial model as a protection from the short- sighted results which the majority of mono-factorial approaches produce, this report starts with the analysis of the distinct role which the Armed Forces of each country have had in the historical evolution of their respective civil-military relations up to 1980 (Part One of Chapters Two and Three). -

Biography of Harold Dwight Lasswell

NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES H A R O L D D W I G H T L ASS W ELL 1902—1978 A Biographical Memoir by GA BRIEL A. ALMOND Any opinions expressed in this memoir are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Academy of Sciences. Biographical Memoir COPYRIGHT 1987 NATIONAL ACADEMY OF SCIENCES WASHINGTON D.C. HAROLD DWIGHT LASSWELL February 13, 1902-December 18, 1978 BY GABRIEL A. ALMOND AROLD D. LASSWELL ranks among the half dozen cre- Hative innovators in the social sciences in the twentieth century. Few would question that he was the most original and productive political scientist of his time. While still in his twenties and early thirties, he planned and carried out a re- search program demonstrating the importance of personal- ity, social structure, and culture in the explanation of political phenomena. In the course of that work he employed an array of methodologies that included clinical and other kinds of interviewing, content analysis, para-experimental tech- niques, and statistical measurement. It is noteworthy that two decades were to elapse before this kind of research program and methodology became the common property of a disci- pline that until then had been dominated by historical, legal, and philosophical methods. Lasswell was born in 1902 in Donnellson, Illinois (popu- lation ca. 300). His father was a Presbyterian clergyman, his mother, a teacher; an older brother died in childhood. His early family life was spent in small towns in Illinois and In- diana as his father moved from one pulpit to another, and it stressed intellectual and religious values. -

Giving Hands and Feet to Morality

Perspectives Forum on the Chicago School of Political Science Giving Hands and Feet to Morality By Michael Neblo f you look closely at the stone engraving that names the Social the increasing sense of human dignity on the other, makes possible a Science Research building at the University of Chicago, you far more intelligent form of government than ever before in history.2 Ican see a curious patch after the e in Science. Legend has it the By highlighting their debt to pragmatism and progressivism, I patch covers an s that Robert Maynard Hutchins ordered do not mean to diminish Merriam’s and Lasswell’s accom- stricken; there is only one social science, Hutchins insisted. plishments, but only to situate and explain them in a way con- I do not know whether the legend is true, but it casts in an gruent with these innovators’ original motivations. Merriam interesting light the late Gabriel Almond’s critique of intended the techniques of behavioral political science to aug- Hutchins for “losing” the ment and more fully realize Chicago school of political the aims of “traditional” polit- science.1 Lamenting the loss, Political science did not so much “lose” the ical science—what we would Almond tries to explain the now call political theory. rise of behavioral political sci- Chicago school as walk away from it. Lasswell agreed, noting that ence at Chicago and its subse- the aim of the behavioral sci- quent fall into institutional entist “is nothing less than to give hands and feet to morality.”3 neglect. Ironically, given the topic, he alights on ideographic Lasswell’s protégé, a young Gabriel Almond, went even explanations for both phenomena, locating them in the per- further: sons of Charles Merriam and Hutchins, respectively. -

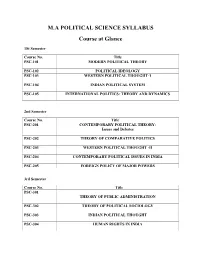

M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE SYLLABUS Course at Glance

M.A POLITICAL SCIENCE SYLLABUS Course at Glance 1St Semester Course No. Title PSC-101 MODERN POLITICAL THEORY PSC-102 POLITICAL IDEOLOGY PSC-103 WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT-1 PSC-104 INDIAN POLITICAL SYSTEM PSC-105 INTERNATIONAL POLITICS: THEORY AND DYNAMICS 2nd Semester Course No. Title PSC-201 CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL THEORY: Issues and Debates PSC-202 THEORY OF COMPARATIVE POLITICS PSC-203 WESTERN POLITICAL THOUGHT -II PSC-204 CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL ISSUES IN INDIA PSC-205 FOREIGN POLICY OF MAJOR POWERS 3rd Semester Course No. Title PSC-301 THEORY OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION PSC-302 THEORY OF POLITICAL SOCIOLOGY PSC-303 INDIAN POLITICAL THOUGHT PSC-304 HUMAN RIGHTS IN INDIA PSC-305 INDIA IN WORLD AFFAIRS 4th Semester Course No. Title PSC-401 CHANGING DIMENSIONS OF PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION IN INDIA PSC-402 INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZIATION AND ADMINISTRIATION PSC-403 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY PSC-404 COMPUTER BASICS: THEORY AND PRACTICE Elective CONTEMPORARY POLITICAL THOUGHT PSC-405 (i) 405 (ii) LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN INDIA 405 (iii) ETHICS AND POLITICS 405 (iv) COMPARATIVE FEDERALISM 405 (v) SOCIAL EXCLUSION IN INDIA Courses of Studies for M.A. in Political Science (Under Semester System of Teaching & Examination Effective from the Academic Session 2016-17) SEMESTER-I Course No. PSC-101 MODERN POLITICAL THEORY Unit-I (i) Political Theory- Evolution, The Traditional Approach; Nature and Scope of Traditional Political Theory; Prime Concerns. (ii) Modern Political Theory- Genesis and Evolution; The Modern Behavioural Approach; Nature and Scope of Modern Political Theory; Prime Concerns. Unit-II (i) Political Decision-making Theory of Harold. D. Laswell – The Concept of Politics as the Societal Decision-making Process; Classification of Societal Values; Role of Elites in the Societal Decision-making Process; Effectiveness and Legitimacy of the Societal Decision-making Structure. -

1 Extending the Legacy of Morris Janowitz: Pragmatism, International

Extending the Legacy of Morris Janowitz: Pragmatism, International Relations and Peacekeeping Patricia Shields Texas State University [email protected] Joseph Soeters Netherlands Defence Academy Tilburg University [email protected] Presented at the European Group on Military and Society (ERGOMAS) Biannual Conference, June 4-7, 2013, Madrid 1 Introduction The use of force in international relations has been so altered that it seems appropriate to speak of constabulary forces, rather than of military forces. The constabulary concept provides a continuity with past military experiences and traditions ….. The constabulary outlook is grounded in, and extends, pragmatic doctrine Janowitz, 1971 p. 418 “Peacekeeping is intended to assist in the creation and maintenance of conditions conducive to long-term conflict resolution” (Bellamy et al, p.95). The resolution of these conflicts, however, is often facilitated by mediation efforts within and between nations and may not adhere to any particular traditional theory of international relations (IR). Peace support operations are carried out by dynamic international coalitions mostly under the aegis of the United Nations (UN), sometimes headed by other alliances such as NATO, the European Union or the African Union. Unfortunately, their record is mixed at best. They represent an important type of sub-national nexus event, which requires the development of new approaches to international relations theories. Throughout Europe, for example, nations are reshaping their militaries to take on new missions (Furst and Kummel 2011). Peace support and stability operations are chief among them. Conventional international relations theory, however, is weakly suited for making sense of and explaining these missions. Long-established approaches to international relations such as realism and liberal internationalism share assumptions about how the world operates.1 Unfortunately, in many international disputes strict adherence to fundamentalist thinking tends to reinforce 1 E.g.