The Siege of Tobruk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Medical Conditions in the Western Desert and Tobruk

CHAPTER 1 1 MEDICAL CONDITIONS IN THE WESTERN DESERT AND TOBRU K ON S I D E R A T I O N of the medical and surgical conditions encountered C by Australian forces in the campaign of 1940-1941 in the Wester n Desert and during the siege of Tobruk embraces the various diseases me t and the nature of surgical work performed . In addition it must includ e some assessment of the general health of the men, which does not mean merely the absence of demonstrable disease . Matters relating to organisa- tion are more appropriately dealt with in a later chapter in which the lessons of the experiences in the Middle East are examined . As told in Chapter 7, the forward surgical work was done in a main dressing statio n during the battles of Bardia and Tobruk . It is admitted that a serious difficulty of this arrangement was that men had to be held for some tim e in the M.D.S., which put a brake on the movements of the field ambulance , especially as only the most severely wounded men were operated on i n the M.D.S. as a rule, the others being sent to a casualty clearing statio n at least 150 miles away . Dispersal of the tents multiplied the work of the staff considerably. SURGICAL CONDITIONS IN THE DESER T Though battle casualties were not numerous, the value of being able to deal with varied types of wounds was apparent . In the Bardia and Tobruk actions abdominal wounds were few. Major J. -

Brevity, Skorpion & Battleaxe

DESERT WAR PART THREE: BREVITY, SKORPION & BATTLEAXE OPERATION BREVITY MAY 15 – 16 1941 Operation Sonnenblume had seen Rommel rapidly drive the distracted and over-stretched British and Commonwealth forces in Cyrenaica back across the Egyptian border. Although the battlefront now lay in the border area, the port city of Tobruk - 100 miles inside Libya - had resisted the Axis advance, and its substantial Australian and British garrison of around 27,000 troops constituted a significant threat to Rommel's lengthy supply chain. He therefore committed his main strength to besieging the city, leaving the front line only thinly held. Conceived by the Commander-in-Chief of the British Middle East Command, General Archibald Wavell, Operation Brevity was a limited Allied offensive conducted in mid-May 1941. Brevity was intended to be a rapid blow against weak Axis front-line forces in the Sollum - Capuzzo - Bardia area of the border between Egypt and Libya. Operation Brevity's main objectives were to gain territory from which to launch a further planned offensive toward the besieged Tobruk, and the depletion of German and Italian forces in the region. With limited battle-ready units to draw on in the wake of Rommel's recent successes, on May 15 Brigadier William Gott, with the 22nd Guards Brigade and elements of the 7th Armoured Division attacked in three columns. The Royal Air Force allocated all available fighters and a small force of bombers to the operation. The strategically important Halfaya Pass was taken against stiff Italian opposition. Reaching the top of the Halfaya Pass, the 22nd Guards Brigade came under heavy fire from an Italian Bersaglieri (Marksmen) infantry company, supported by anti-tank guns, under the command of Colonel Ugo Montemurro. -

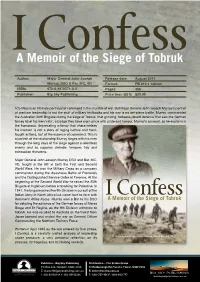

A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk

I Confess A Memoir of the Siege of Tobruk Author: Major General John Joseph Release date: August 2011 Murray, DSO & Bar, MC, VD Format: PB 210 x 148mm ISBN: 978-0-9870574-8-8 Pages: 256 Publisher: Big Sky Publishing Price (incl. GST): $29.99 I Confess is an intimate portrayal of command in the crucible of war. But Major General John Joseph Murray’s portrait of wartime leadership is not the stuff of military textbooks and his war is no set-piece battle. Murray commanded the Australian 20th Brigade during the siege of Tobruk, that grinding, tortuous desert defence that saw the German forces label his men ‘rats’, a badge they have worn since with pride and honour. Murray’s account, as he explains in the humorous, deprecating whimsy that characterises his memoir, is not a story of raging battles and hard- fought actions, but of the essence of command. This is a portrait of the relationship Murray forges with his men through the long days of the siege against a relentless enemy and as supplies dwindle, tempers fray and exhaustion threatens. Major General John Joseph Murray DSO and Bar, MC, VD, fought in the AIF in both the First and Second World Wars. He won the Military Cross as a company commander during the disastrous Battle of Fromelles and the Distinguished Service Order at Peronne. At the beginning of the Second World War he raised the 20th Brigade at Ingleburn before embarking for Palestine. In 1941, the brigade joined the 9th Division in pursuit of the Italian Army in North Africa but came face to face with Rommel’s Afrika Korps. -

The Pillars of American Grand Strategy in World War II by Tami Davis Biddle

Leveraging Strength: The Pillars of American Grand Strategy in World War II by Tami Davis Biddle Tami Davis Biddle is the Hoyt S. Vandenberg Chair of Aerospace Studies at the U.S. Army War College in Carlisle, PA. She is the author of Rhetoric and Reality in Air Warfare: The Evolution of British and American Thinking about Strategic Bombing, 1914–1945, and is at work on a new book titled, Taking Command: The United States at War, 1944–1945. This article is based on a lecture she delivered in March 2010 in The Hertog Program on Grand Strategy, jointly sponsored by Temple University’s Center for Force and Diplomacy, and FPRI. Abstract: This article argues that U.S. leaders navigated their way through World War II challenges in several important ways. These included: sustaining a functional civil-military relationship; mobilizing inside a democratic, capitalist paradigm; leveraging the moral high ground ceded to them by their enemies; cultivating their ongoing relationship with the British, and embra- cing a kind of adaptability and resiliency that facilitated their ability to learn from mistakes and take advantage of their enemies’ mistakes. ooking back on their World War II experience from the vantage point of the twenty-first century, Americans are struck, first of all, by the speed L with which everything was accomplished: armies were raised, fleets of planes and ships were built, setbacks were overcome, and great victories were won—all in a mere 45 months. Between December 1941 and August 1945, Americans faced extraordinary challenges and accepted responsibilities they had previously eschewed. -

Canadian Infantry Combat Training During the Second World War

SHARPENING THE SABRE: CANADIAN INFANTRY COMBAT TRAINING DURING THE SECOND WORLD WAR By R. DANIEL PELLERIN BBA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2007 BA (Honours), Wilfrid Laurier University, 2008 MA, University of Waterloo, 2009 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Doctor of Philosophy degree in History University of Ottawa Ottawa, Ontario, Canada © Raymond Daniel Ryan Pellerin, Ottawa, Canada, 2016 ii ABSTRACT “Sharpening the Sabre: Canadian Infantry Combat Training during the Second World War” Author: R. Daniel Pellerin Supervisor: Serge Marc Durflinger 2016 During the Second World War, training was the Canadian Army’s longest sustained activity. Aside from isolated engagements at Hong Kong and Dieppe, the Canadians did not fight in a protracted campaign until the invasion of Sicily in July 1943. The years that Canadian infantry units spent training in the United Kingdom were formative in the history of the Canadian Army. Despite what much of the historical literature has suggested, training succeeded in making the Canadian infantry capable of succeeding in battle against German forces. Canadian infantry training showed a definite progression towards professionalism and away from a pervasive prewar mentality that the infantry was a largely unskilled arm and that training infantrymen did not require special expertise. From 1939 to 1941, Canadian infantry training suffered from problems ranging from equipment shortages to poor senior leadership. In late 1941, the Canadians were introduced to a new method of training called “battle drill,” which broke tactical manoeuvres into simple movements, encouraged initiative among junior leaders, and greatly boosted the men’s morale. -

![Infantry Division (1941-43)]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3816/infantry-division-1941-43-583816.webp)

Infantry Division (1941-43)]

7 February 2017 [6 (70) INFANTRY DIVISION (1941-43)] th 6 Infantry Division (1) Headquarters, 6th Infantry Division & Employment Platoon 14th Infantry Brigade (2) Headquarters, 14th Infantry Brigade & Signal Section 1st Bn. The Bedfordshire and Hertfordshire Regiment 2nd Bn. The York and Lancaster Regiment 2nd Bn. The Black Watch (Royal Highland Regiment) 16th Infantry Brigade (3) Headquarters, 16th Infantry Brigade & Signal Section 2nd Bn. The Leicestershire Regiment 2nd Bn. The Queen’s Royal Regiment (West Surrey) 1st Bn. The Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders (Princess Louise’s) (4) 23rd Infantry Brigade (5) Headquarters, 23rd Infantry Brigade & Signal Section 4th (Westmorland) Bn. The Border Regiment 1st Bn. The Durham Light Infantry (6) Czechoslovak Infantry Battalion No 11 East (7) Divisional Troops 60th (North Midland) Field Regiment, Royal Artillery (8) (H.Q., 237th (Lincoln) & 238th (Grimsby) Field Batteries, Royal Artillery) 2nd Field Company, Royal Engineers 12th Field Company, Royal Engineers 54th Field Company, Royal Engineers 219th (1st London) Field Park Company, Royal Engineers 6th Divisional Signals, Royal Corps of Signals © www.BritishMilitaryH istory.co.uk Page 1 7 February 2017 [6 (70) INFANTRY DIVISION (1941-43)] Headquarters, 6th Infantry Divisional Royal Army Service Corps (9) 61st Company, Royal Army Service Corps 145th Company, Royal Army Service Corps 419th Company, Royal Army Service Corps Headquarters, 6th Infantry Divisional Royal Army Medical Corps (10) 173rd Field Ambulance, Royal Army Medical Corps 189th -

Soldiers and Statesmen

, SOLDIERS AND STATESMEN For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402 - Price $2.65 Stock Number008-070-00335-0 Catalog Number D 301.78:970 The Military History Symposium is sponsored jointly by the Department of History and the Association of Graduates, United States Air Force Academy 1970 Military History Symposium Steering Committee: Colonel Alfred F. Hurley, Chairman Lt. Colonel Elliott L. Johnson Major David MacIsaac, Executive Director Captain Donald W. Nelson, Deputy Director Captain Frederick L. Metcalf SOLDIERS AND STATESMEN The Proceedings of the 4th Military History Symposium United States Air Force Academy 22-23 October 1970 Edited by Monte D. Wright, Lt. Colonel, USAF, Air Force Academy and Lawrence J. Paszek, Office of Air Force History Office of Air Force History, Headquarters USAF and United States Air Force Academy Washington: 1973 The Military History Symposia of the USAF Academy 1. May 1967. Current Concepts in Military History. Proceedings not published. 2. May 1968. Command and Commanders in Modem Warfare. Proceedings published: Colorado Springs: USAF Academy, 1269; 2d ed., enlarged, Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1972. 3. May 1969. Science, Technology, and Warfare. Proceedings published: Washington, b.C.: Government Printing Office, 197 1. 4. October 1970. Soldiers and Statesmen. Present volume. 5. October 1972. The Military and Society. Proceedings to be published. Views or opinions expressed or implied in this publication are those of the authors and are not to be construed as carrying official sanction of the Department of the Air Force or of the United States Air Force Academy. -

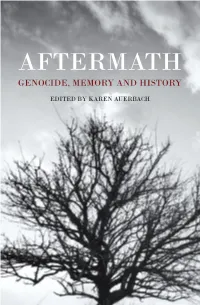

Genocide, Memory and History

AFTERMATH GENOCIDE, MEMORY AND HISTORY EDITED BY KAREN AUERBACH AFTERMATH AFTERMATH GENOCIDE, MEMORY AND HISTORY EDITED BY KAREN AUERBACH Aftermath: Genocide, Memory and History © Copyright 2015 Copyright of the individual chapters is held by the chapter’s author/s. Copyright of this edited collection is held by Karen Auerbach. All rights reserved. Apart from any uses permitted by Australia’s Copyright Act 1968, no part of this book may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission from the copyright owners. Inquiries should be directed to the publisher. Monash University Publishing Matheson Library and Information Services Building 40 Exhibition Walk Monash University Clayton, Victoria, 3800, Australia www.publishing.monash.edu Monash University Publishing brings to the world publications which advance the best traditions of humane and enlightened thought. Monash University Publishing titles pass through a rigorous process of independent peer review. www.publishing.monash.edu/books/agmh-9781922235633.html Design: Les Thomas ISBN: 978-1-922235-63-3 (paperback) ISBN: 978-1-922235-64-0 (PDF) ISBN: 978-1-876924-84-3 (epub) National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Title: Aftermath : genocide, memory and history / editor Karen Auerbach ISBN 9781922235633 (paperback) Series: History Subjects: Genocide. Genocide--Political aspects. Collective memory--Political aspects. Memorialization--Political aspects. Other Creators/Contributors: Auerbach, Karen, editor. Dewey Number: 304.663 CONTENTS Introduction ............................................... -

World War Ii (1939–1945) 56 57

OXFORD BIG IDEAS HISTORY 10: AUSTRALIAN CURRICULUM 2 WORLD WAR II (1939–1945) 56 57 depth study World War II In this depth study, students will investigate wartime experiences through a study of World War II. is includes coverage of the causes, events, outcome and broad impact of the con ict as a part of global history, as well as the nature and extent of Australia’s involvement in the con ict. is depth study MUST be completed by all students. 2.0 World War II (1939–1945) The explosion of the USS Shaw during the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, 7 December 1941 SAMPLE OXFORD BIG IDEAS HISTORY 10: AUSTRALIAN CURRICULUM 2 WORLD WAR II (1939–1945) 58 59 Australian Curriculum focus HISTORICAL KNOWLEDGE AND UNDERSTANDING • An overview of the causes and course of World War II • An examination of significant events of World War II, including the Holocaust and use of the atomic bomb depth study • The experiences of Australians during World War II (such as Prisoners of War (POWs), the Battle of Britain, World War II Kokoda, the Fall of Singapore) (1939–1945) • The impact of World War II, with a particular emphasis on the Australian home front, including the changing roles of women and use of wartime government World War II was one of the de ning events of the 20th century. e war was controls (conscription, manpower controls, rationing played out all across Europe, the Paci c, the Middle East, Africa and Asia. and censorship) e war even brie y reached North America and mainland Australia. -

The Greatest Military Reversal of South African Arms: the Fall of Tobruk 1942, an Avoidable Blunder Or an Inevitable Disaster?

THE GREATEST MILITARY REVERSAL OF SOUTH AFRICAN ARMS: THE FALL OF TOBRUK 1942, AN AVOIDABLE BLUNDER OR AN INEVITABLE DISASTER? David Katz1 Abstract The surrender of Tobruk 70 years ago was a major catastrophe for the Allied war effort, considerably weakening their military position in North Africa, as well as causing political embarrassment to the leaders of South Africa and the United Kingdom. This article re-examines the circumstances surrounding and leading to the surrender of Tobruk in June 1942, in what amounted to the largest reversal of arms suffered by South Africa in its military history. By making use of primary documents and secondary sources as evidence, the article seeks a better understanding of the events that surrounded this tragedy. A brief background is given in the form of a chronological synopsis of the battles and manoeuvres leading up to the investment of Tobruk, followed by a detailed account of the offensive launched on 20 June 1942 by the Germans on the hapless defenders. The sudden and unexpected surrender of the garrison is examined and an explanation for the rapid collapse offered, as well as considering what may have transpired had the garrison been better prepared and led. Keywords: South Africa; HB Klopper; Union War Histories; Freeborn; Gazala; Eighth Army; 1st South African Division; Court of Enquiry; North Africa. Sleutelwoorde: Suid-Afrika; HB Klopper; Uniale oorlogsgeskiedenis; Vrygebore; Gazala; Agste Landmag; Eerste Suid-Afrikaanse Bataljon; Hof van Ondersoek; Noord-Afrika. 1. INTRODUCTION This year marks the 70th anniversary of the fall of Tobruk, the largest reversal of arms suffered by South Africa in its military history. -

Montgomery and Eisenhower's British Officers

MONTGOMERY AND SHAEF Montgomery and Eisenhower’s British Officers MALCOLM PILL Independent Scholar Email: [email protected] ABSTRACT When the British and American Governments established an Allied Expeditionary Force to liberate Nazi occupied Western Europe in the Second World War, General Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Commander and General Montgomery appointed to command British ground forces and, for the initial stages of the operation, all ground forces. Senior British Army officers, Lieutenant-General F. E. Morgan, formerly Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC), and three officers from the Mediterranean theatre, Lieutenant-General K. Strong, Major-General H. Gale and Major-General J. Whiteley, served at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). The purpose of this article is to demonstrate the aggressively hostile attitude of Montgomery towards the British officers, to analyse the reasons for it and to consider whether it was justified. The entry of the United States into the Second World War in December 1941 provided an opportunity for a joint command to undertake a very large and complex military operation, the invasion of Nazi occupied Western Europe. Britain would be the base for the operation and substantial British and American forces would be involved. At the Casablanca Conference in January 1943 Winston Churchill and Franklin Roosevelt set up an integrated Allied planning staff with a view to preparing the invasion. In April 1943, Lieutenant-General Frederick Morgan was appointed Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander (COSSAC) for the operation, an appointment approved by Churchill following a lunch with Morgan at Chequers. Eight months later, in December 1943, General Eisenhower was appointed Supreme Commander and the staff at COSSAC, including Morgan, merged into Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF). -

Book a Facilitated Program for 2011 and We Will Provide a Much Deeper

EDUCATION SERVICES 2 011 Tobruk Ray Ewers and George Browning, 1954-56 AWM ART41035 Book a facilitated program for 2011 and we will provide a much deeper learning experience. RelAWM31948.004 Tobruk 1941 – A Gallant Information For Teachers and Tenacious Defence Book a facilitated program for your school group; a program will provide a much deeper learning experience. New programs, aligned to the Australian The whole empire is watching your steadfast and Curriculum for History, are now available. spirited defence … with gratitude and admiration. Prime Minister Winston Churchill The Australian War Memorial provides a wide range of REL07652 Teacher’s checklist educational programs aligned with the new Australian Curriculum for History. These programs are designed to Log on to www.awm.gov.au/education and read about the Memorial’s curriculum-based programs and choose The fate of the war in North Africa hung on the possession protect it ran in a rough semicircle across the desert suit your classroom and curriculum needs. which program best suits the needs of your students. of a small harbour town in the far corner of the Libyan desert from coast to coast, and consisted of dozens of concrete- When you visit the Memorial, and book a facilitated – Tobruk. It was vital for the Allies’ defence of Egypt and the sided strong-points protected by barbed-wire fences and program, students gain a much deeper learning Book your visit online and record your booking Suez Canal to hold the town with its harbour, as this forced anti-tank ditches. experience. Our trained educators draw on personal reference number.