Mapping Paths to Family Justice Resolving Family Disputes in Neoliberal Times

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

There If Often a Fine Line Between Reporting Crimes and Encouraging Criminals

Media Law: Keep Your Distance: There if Often a Fine Line Between Reporting Crimes and Encouraging Criminals By Duncan Lamont The Guardian September 20, 2004, p 10 An angry father perched on a Buckingham Palace ledge in a Batman suit may have seemed a bit of a laugh but the stunt raised some potentially uncomfortable legal issues. For a start, Batman (Jason Hatch) could easily have been shot. His sidekick, Dave Pyke (dressed as Robin), was following him up the ladder when an officer pointed a handgun at him and shouted "Come down or I will shoot". So down he came. Metropolitan police commissioner Sir John Stevens pointed out that the alarms and CCTV had operated and that if it had been thought that Batman was carrying a bomb "he would have been shot". Terrorists may now have noticed that silly clothes seem to gain the wearer free access to both Parliament and royal palaces. Thankfully, the media were not reporting shootings but providing the very oxygen of publicity that Fathers 4 Justice craved. The Daily Mirror boasted last week that its reporters were at the group's weekend summit (which apparently turned into a foul-mouthed drinking session). And they would have been aware that this was not merely boasting - Hatch is due in court later this year concerning a demonstration on Clifton Suspension Bridge in Bristol. The Daily Mail was also in the know and printed 12 photographs, showing the protesters from the moment they jumped the railings and propped a ladder against the side of the building, to Hatch's eventual descent, six hours later, in a cherry picker. -

Every Father Is a Superhero to His Children: the Gendered

bs_bs_banner POLITICAL STUDIES: 2013 doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2012.01008.x ‘Every Father is a Superhero to His Children’: The Gendered Politics of the (Real) Fathers 4 Justice Campaign Ana Jordan University of Lincoln Fathers’ rights groups have been characterised by some feminist academics as part of an anti-feminist ‘backlash’, responding to a perceived crisis of masculinity through a problematic politics of fatherhood aimed at (re)asserting control over women and children.This article analyses the construction of gender and masculinity/ies within fathers’ rights groups, specifically,the UK-based pressure group, (Real) Fathers 4 Justice.The article explores the construction of power-laden gender identity/ies within (Real) Fathers 4 Justice and, in doing so, contributes to understanding the logic and implications of fathers’ rights perspectives. The analysis is based on in-depth interviews conducted with members of the group.The qualitative case study is used to explore critically the (gender) politics of fathers’ rights. It is argued that the interviewees (re)construct multiple masculinities: bourgeois-rational masculinity, new man/new father masculinity and hypermasculinity.These masculinity frames intersect with broader constructions of gender and need to be understood in evaluating the perspectives of fathers’ rights groups which are complex in terms of their implications for gender politics broadly conceived. Overall, it is argued that each of the masculinity frames can be problematic, as they reinforce existing gendered binaries. Keywords: pressure groups; fathers’ rights; masculinities; gender politics; social movements This article critically interrogates the politics of fathers’ rights from a feminist perspective, analysing the gendered (and heteronormative) logic underpinning fathers’ rights perspec- tives.The identity of ‘father’has always been political as power-laden gendered identities are implicit within constructions of fatherhood. -

Working with Men in Health and Social Care

Featherstone(Working)-3556-Prelims.qxd 5/24/2007 10:39 AM Page i Working with Men in Health and Social Care Featherstone(Working)-3556-Prelims.qxd 5/24/2007 10:39 AM Page ii Featherstone(Working)-3556-Prelims.qxd 5/24/2007 10:39 AM Page iii Working with Men in Health and Social Care Brid Featherstone Mark Rivett and Jonathan Scourfield Featherstone(Working)-3556-Prelims.qxd 5/24/2007 10:39 AM Page iv © Brid Featherstone, Mark Rivett and Jonathan Scourfield 2007 First published 2007 Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of research or private study, or criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, this publication may be reproduced, stored or transmitted in any form, or by any means, only with the prior permission in writing of the publishers, or in the case of reprographic reproduction, in accordance with the terms of licences issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency. Enquiries concerning reproduction outside those terms should be sent to the publishers. SAGE Publications Ltd 1 Oliver’s Yard 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP SAGE Publications Inc. 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, California 91320 SAGE Publications India Pvt Ltd B 1/I 1 Mohan Cooperative Industrial Area Mathura Road New Delhi 110 044 SAGE Publications Asia-Pacific Pte Ltd 33 Pekin Street #02-01 Far East Square Singapore 048763 Library of Congress Control Number: 2006939013 British Library Cataloguing in Publication data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 978-1-4129-1849-7 ISBN 978-1-4129-1850-3 (pbk) Typeset by C&M Digitals (P) Ltd., Chennai, India Printed on paper from sustainable resources Printed in India by Replika Press Pvt. -

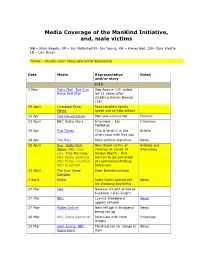

Media Coverage of the Mankind Initiative, And, Male Victims

Media Coverage of the ManKind Initiative, and, male victims MB – Mark Brooks, IM – Ian McNicholl,IY- Ian Young, KB – Kieron Bell, SW- Sara Westle LB – Lori Busch Yellow – denote court cases and initial disclosures Date Media Representative Detail and/or story 2018 3 May Daily Mail, The Sun, Zoe Adams (19) jailed News and Star for 11 years after stabbing Kieran Bewick (18) 29 April Liverpool Echo, Paul Lavelle’s family Metro speak out to help others 26 Apr The Conversation Men are victims too Feature 23 April BBC Radio Worc Interview – Ian Interview McNicholl 19 Apr The Times This is what it is like Article when your wife hits you 18 Apr The Sun Male victims statistics News 16 April Sun, Daily Mail, Alex Skeel victim of Articles and Metro, BBC Five violence at hands of interviews Live, This Morning, Jordan Worth - first BBC Radio Scotland, woman to be convicted BBC Three Counties, of coercive/controlling BBC Breakfast behaviour 13 April The Sun (Dear Dear Deirdre column Deirdre) 7 April Mirror Jodie Owen spared jail News for stabbing boyfriend 29 Mar Mail Nasreen Knight attacked husband Julian knight 27 Mar BBC Lavinia Woodward News appeal refused 27 Mar Wales Online New refuge in Bridgend News being set up 26 Mar BBC Radio Somerset Interview with Mark Interview Brooks 23 Mar Kent online, BBC ManKind call for refuge in News Radio Kent Kent 14-16 Mar Stoke Sentinel, BBC Pete Davegun fundraiser Radio Stoke, Crewe Guardian, Staffs Live 19 Mar Victoria Derbyshire Mark Brooks interview Interview 12 Mar Somerset Live ManKind Initiative appeal -

Whole Day Download the Hansard

Wednesday Volume 622 1 March 2017 No. 117 HOUSE OF COMMONS OFFICIAL REPORT PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) Wednesday 1 March 2017 © Parliamentary Copyright House of Commons 2017 This publication may be reproduced under the terms of the Open Parliament licence, which is published at www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/. 277 1 MARCH 2017 278 deliver that and it is for them to choose how they use House of Commons them, but they do have to account for their use to the people of Scotland. Wednesday 1 March 2017 Simon Hoare: Does my hon. Friend share my confusion that the Scottish Government prefer the narrative of The House met at half-past Eleven o’clock whinge, whine and waffle to using the powers that this Parliament has given them to prove their competence in running the country? PRAYERS Jane Ellison: As I am sure many hon. Members also know, I am very aware from many of my conversations [MR SPEAKER in the Chair] with businesses—particularly those thinking about their plans for the future, especially since the referendum last BUSINESS BEFORE QUESTIONS year—that they often see competitiveness through the prism of tax and that they want to know the Government MIDDLE LEVEL BILL (BY ORDER) are entirely focused on creating the conditions in which Second Reading opposed and deferred until Wednesday businesses can grow and thrive. I really think that all of 8 March (Standing Order No. 20). us need to focus on pursuing our plans to make our respective countries very competitive. In Scotland, the Government have to understand that the decisions they take about using their powers are part of such a package Oral Answers to Questions for businesses. -

The Operation of the Family Courts

House of Commons Constitutional Affairs Committee Family Justice: the operation of the family courts Fourth Report of Session 2004–05 Volume II Oral and written evidence Ordered by The House of Commons to be printed 23 February 2005 HC 116-II [Incorporating HC 1247-i, Session 2003-04 and HC 116-i to iv] Published on 2 March 2005 by authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited £20.50 Witnesses Tuesday 9 November 2004 Rt Hon Dame Elizabeth Butler-Sloss DBE, President, High Court, Family Division, Rt Hon Lord Justice Wall Hon Mr Justice Munby Ev 1 His Honour Judge Meston QC District Judge Michael Walker District Judge Nicholas Crichton Ev 14 Tuesday 7 December 2004 Christina Blacklaws and Hilary Lloyd, The Law Society Kim Beatson and Christopher Goulden, The Solicitors Family Law Association Philip Moor QC, The Family Law Bar Association Ev 22 Tuesday 14 December 2004 Hilary Saunders, Women’s Aid Ruth Aitken, Refuge Phillip Noyes and Barbara Esam, NSPCC Ev 34 Mavis Maclean CBE and John Eekelaar, Oxford University Ev 40 Anthony Douglas and Baroness Pitkeathley OBE, CAFCASS Ev 44 Tuesday 11 January 2005 Caroline Abrahams and Susannah Weekes, NCH Margaret Pendlebury, National Family Mediation Ev 49 Tony Coe, Equal Parenting Council John Baker, Families Need Fathers Celia Conrad, former law practitioner and a legal consultant Ev 54 Tuesday 18 January 2005 Baroness Ashton of Upholland, Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State, Department for Constitutional Affairs Rt Hon Margaret Hodge MBE MP, Minister of State for Children, -

Publics Short Memory (Pdf)

A search using the words social services and family court in the Guardian, Mail and Times revealed the short memories of the Public, the revamping of issues year after year and yet despite promises to improve the system is getting worse....enjoy.... 1 Media access to make family courts 'accountable' 11/07/2006 10:47:30 Family courts could be opened up to the Press under Government proposals designed to make them more 'accountable'. Children would also be able to access details of judgments when they reach the age of 18.....read 2 Family murder convictions quashed by appeal court 03/05/2005 12:41:50 A former scrap metal dealer who was jailed for life for the brutal murder of three generations of one family in Wales had his convictions quashed today by the appeal court. David Morris mouthed the word 'yes' as the appeal court in Cardiff ruled that a conflict of interest made his four convictions for murder unsafe.....read 3 Family anger as right-to-life baby Luke dies 12/11/2004 10:13:42 The family of a terminally-ill baby whose life-saving treatment was withheld by order of the courts today demanded an inquiry into the medical care he received in his final hours. The mother of the ten- month-old, who had been given only days to live after birth, said it was 'the end of my world'.....read 4 Judge: Family justice failed father 01/04/2004 14:50:12 A High Court judge has launched an astonishing attack on the family justice system which he said had failed a father who has not seen his daughter since October 2001......read 6 Protesting fathers' court occupation 13/06/2003 17:20:12 A civil rights group campaigning to give fathers a louder voice in law staged a protest occupation of a court room in the Family Division of the High Court......read 1 You can't silence justice 01/11/2006 09:12:38 As a judge threatens to censor reporting of family courts, blaming the Mail's coverage of a heart- rending case.. -

Fathers 4 Justice, Law and the New Politics of Fatherhood

Page 1 3 of 206 DOCUMENTS © Jordan Publishing Limited 2005 Child and Family Law Quarterly 1 December 2005 CFam 17 4 (511) LENGTH: 9874 words TOPIC: CHILDREN AND YOUNG PERSONS TITLE: Fathers 4 Justice, law and the new politics of fatherhood AUTHOR: Richard Collier n* LEGISLATION REFERRED TO: the Children Act 1989; The Family Law Reform Act 1995 TEXT: Who are those guys? What does it all mean --the Marvel Comics costumes, the orchestrated gantry stunts, the banners, the Santa outfits, the nooses, the desperate measures? n1 If you give a father no options, you leave him no choice. Fatherhood is under attack in a way inconceivable 30 years ago. n2 INTRODUCTION Divorce law has long been a site of contestation and struggle. The question of how law responds to the 'transformations of intimacy' n3 which frame family practices n4 has been, in a sense, the very stuff of family law. There are signs, however, that the nature of these struggles may be changing in the area of post--divorce/separation contact. The legal status, responsibilities and rights of men who are fathers --married or unmarried, cohabiting or separated, biological or social in nature --is a topic with a long and well--documentedhistory. Yet recent events in the UK and elsewhere suggest a heightening of concern about --and, in particular, a growing politicisation of --the relationship between law and fatherhood. n5 This article seeks to address the arguments presented by, and possible impact of, fathers' rights organisations in seeking to set a reform agenda in this area of law in the UK. -

British and Commonwealth Society of North America

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH SOCIETY OF NORTH AMERICA PRESENTS May 31st 2014—Saturday 12:30 pm till!! FISH ˂ ˂ AND PUB LUNCH with Barry!!! At a British Pub (order off CHIPS the menu): At Public House No 7, 6315 Leesburg Pike (near Seven Corners), Falls Church, Virginia 22044 (www.publichouseno7.com) POC: Barry Kelly SAUSAGE ([email protected]) or 703-403-8785 ˂ ˂ ROLLS June 22nd 2014, Sunday 11:30 am to 2:30 pm Annual Commonwealth/AGM Champagne Brunch Fort Myer Officer’s Club, 214 Jackson Avenue, Fort Myer, Virginia 22211. Election of Board—can we get some volunteers for the B&CSNA Board? Very short AGM, it’s mostly enjoyment Cost: $30.00 for members & $33.00 for non members. Cheques must be received NLT June 16th 2014, no refunds after June 16th POC: Regina ([email protected]) 703-892-6522. Send cheques to Regina (made payable to B&CSNA) at: Regina Barker-Barzel, Box 100298, Arlington, Virginia 22210-0864 June 28th 2014 Saturday British Players 50th ANNIVERSARY OLD TIME MUSIC HALL Kensington, Mary- land. With songs of 1914’s WW1 (100 years ago). B&CSNA day will be June 28th (details later). BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH SOCIETY OF NORTH AMERICA—NEWSLETTER MAY—JUNE Page 1 of 12 Editorial Note: property. franchise, was established. In 1953, min- Settlers, using slave labour, devel- isters from the council took over most Articles with By-Lines, sources, items oped sugar, cocoa, indigo and later portfolios, and Bustamante became chief made available to the Editor are pub- coffee estates. The island was very minister. Manley followed, in 1955. -

Manufacturing Dissent Single-Issue Protest, the Public and the Press

Protest is migrating from the streets in to the newspapers. Instead of simply reporting dissent, the media is starting to manufacture it Manufacturing Dissent Single-issue protest, the public and the press Kirsty Milne About Demos Demos is a greenhouse for new ideas which can improve the quality of our lives. As an independent think tank, we aim to create an open resource of knowledge and learning that operates beyond traditional party politics. We connect researchers, thinkers and practitioners to an international network of people changing politics. Our ideas regularly influence government policy, but we also work with companies, NGOs, colleges and professional bodies. Demos knowledge is organised around five themes, which combine to create new perspectives. The themes are democracy, learning, enterprise, quality of life and global change. But we also understand that thinking by itself is not enough. Demos has helped to initiate a number of practical projects which are delivering real social benefit through the redesign of public services. We bring together people from a wide range of backgrounds to cross-fertilise ideas and experience. By working with Demos, our partners develop a sharper insight into the way ideas shape society. For Demos, the process is as important as the final product. www.demos.co.uk First published in 2005 © Demos Some rights reserved – see copyright licence for details ISBN 1 84180 141 0 Typeset by Land & Unwin, Bugbrooke Printed by HenDI Systems, London For further information and subscription details please contact: Demos Magdalen House 136 Tooley Street London SE1 2TU telephone: 0845 458 5949 email: [email protected] web: www.demos.co.uk Manufacturing Dissent Single-issue protest, the public and the press Kirsty Milne Open access.Some rights reserved. -

JIGSAW READINGS OVERVIEW Information on Five Pressure Groups

TASK 1: WHAT IS A PRESSURE GROUP? ACTIVITY 2: JIGSAW READINGS OVERVIEW Information on five pressure groups is presented here. Each organisation has different aims, objectives and views. Further information is available on each organisation’s website. 1 TASK 1: READINGS GREENPEACE Today Greenpeace is a global organisation, campaigning on a range of issues including environmental conservation, nuclear power, whaling, forests, fishing and environmental pollution, weapons disarmament and peace. It seeks to change attitudes and behaviour and promotes the use of sustainable resources and sustainable agriculture. Global warming is a major issue for Greenpeace. Their campaigns have included sailing a ship into an ‘exclusion zone’ in the South Pacific to disrupt nuclear testing in 1972, combined with civil disobedience protests. In 1974 the organisation began anti-whaling protests, followed by an anti fur trade campaign in 1976, and further disruption to whaling ships. The group has also used the courts to fight restrictions on what it can do. Greenpeace has used lobbying (of the United Nations) and direct action, when activists climbed on top of a British airways plane at London’s Heathrow airport in protest at plans for a new runway. The Greenpeace website says… ‘Greenpeace stands for positive change through action. We defend the natural world and promote peace. We investigate, expose and confront environmental abuse by governments and corporations around the world. We champion environmentally responsible and socially just solutions, including -

House of Lords Official Report

Vol. 748 Wednesday No. 53 16 October 2013 PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) HOUSE OF LORDS OFFICIAL REPORT ORDER OF BUSINESS Introduction: Lord Whitby...............................................................................................533 Questions Alcohol: Late Night Drinking .....................................................................................533 EU: Northern Cyprus...................................................................................................535 Identity Cards................................................................................................................537 Northern Ireland: Abortion..........................................................................................540 Anti-social Behaviour, Crime and Policing Bill First Reading..................................................................................................................542 Examiner of Petitions for Private Bills Motion to Appoint.........................................................................................................542 Care Bill [HL] Report (3rd Day)..........................................................................................................543 Probation Service Question for Short Debate............................................................................................606 Care Bill [HL] Report (3rd Day) (Continued) ....................................................................................621 Grand Committee Children and Families Bill Committee (3rd