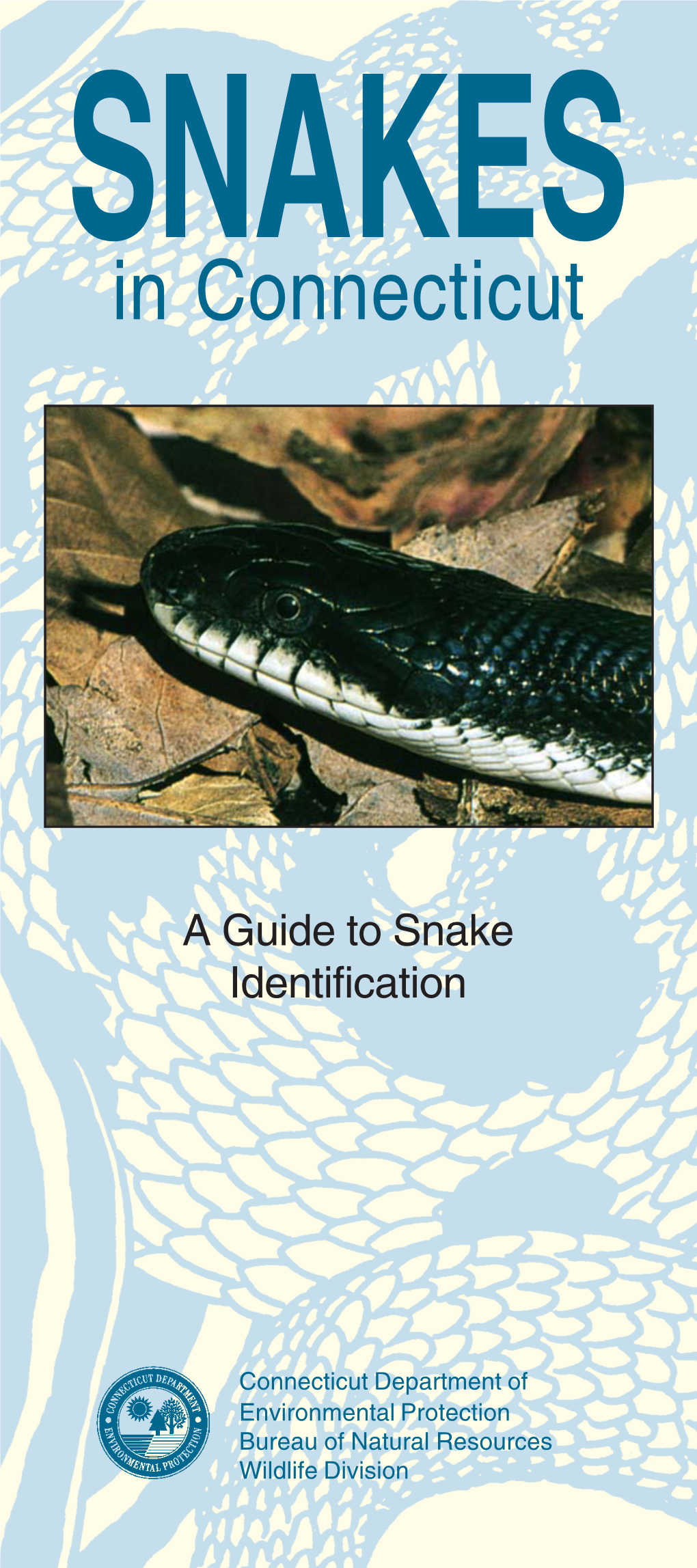

SNAKES in Connecticut

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Timber Rattlesnake: Pennsylvania’S Uncanny Mountain Denizen

The Timber Rattlesnake: Pennsylvania’s Uncanny Mountain Denizen photo-Steve Shaffer by Christopher A. Urban breath, “the only good snake is a dead snake.” Others are Chief, Natural Diversity Section fascinated or drawn to the critter for its perceived danger- ous appeal or unusual size compared to other Pennsylva- Who would think that in one of the most populated nia snakes. If left unprovoked, the timber rattlesnake is states in the eastern U.S., you could find a rattlesnake in actually one of Pennsylvania’s more timid and docile the mountains of Penn’s Woods? As it turns out, most snake species, striking only when cornered or threatened. timber rattlesnakes in Pennsylvania are found on public Needless to say, the Pennsylvania timber rattlesnake is an land above 1,800 feet elevation. Of the three venomous intriguing critter of Pennsylvania’s wilderness. snakes that occur in Pennsylvania, most people have heard about this one. It strikes fear in the hearts of some Description and elicits fascination in others. When the word “rattler” The timber rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus) is a large comes up, you may hear some folks grumble under their (up to 74 inches), heavy-bodied snake of the pit viper www.fish.state.pa.us Pennsylvania Angler & Boater, January-February 2004 17 family (Viperidae). This snake has transverse “V”-shaped or chevronlike dark bands on a gray, yellow, black or brown body color. The tail is completely black with a rattle. The head is large, flat and triangular, with two thermal-sensitive pits between the eyes and the nostrils. The timber rattlesnake’s head color has two distinct color phases. -

Resource Selection by an Ectothermic Predator in a Dynamic Thermal Landscape

Received: 2 May 2017 | Revised: 16 August 2017 | Accepted: 17 August 2017 DOI: 10.1002/ece3.3440 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Resource selection by an ectothermic predator in a dynamic thermal landscape Andrew D. George1 | Grant M. Connette2 | Frank R. Thompson III3 | John Faaborg1 1Division of Biological Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO, USA Abstract 2Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute, Predicting the effects of global climate change on species interactions has remained Front Royal, VA, USA difficult because there is a spatiotemporal mismatch between regional climate models 3U.S.D.A. Forest Service Northern Research and microclimates experienced by organisms. We evaluated resource selection in a Station, Columbia, MO, USA predominant ectothermic predator using a modeling approach that permitted us to Correspondence assess the importance of habitat structure and local real- time air temperatures within Andrew D. George, Department of Biology, Pittsburg State University, Pittsburg, KS USA. the same modeling framework. We radio- tracked 53 western ratsnakes (Pantherophis Email: [email protected] obsoletus) from 2010 to 2013 in central Missouri, USA, at study sites where this spe- cies has previously been linked to prey population demographics. We used Bayesian discrete choice models within an information theoretic framework to evaluate the sea- sonal effects of fine- scale vegetation structure and thermal conditions on ratsnake resource selection. Ratsnake resource selection was influenced most by canopy cover, canopy cover heterogeneity, understory cover, and air temperature heterogeneity. Ratsnakes generally preferred habitats with greater canopy heterogeneity early in the active season, and greater temperature heterogeneity later in the season. This sea- sonal shift potentially reflects differences in resource requirements and thermoregula- tion behavior. -

Downloaded from Brill.Com10/06/2021 09:29:00AM Via Free Access 42 Luiselli Et Al

Contributions to Zoology, 74 (1/2) 41-49 (2005) Analysis of a herpetofaunal community from an altered marshy area in Sicily; with special remarks on habitat use (niche breadth and overlap), relative abundance of lizards and snakes, and the correlation between predator abundance and tail loss in lizards Luca Luiselli1, Francesco M. Angelici2, Massimiliano Di Vittorio3, Antonio Spinnato3, Edoardo Politano4 1 F.I.Z.V. (Ecology), via Olona 7, I-00198 Rome, Italy. E-mail: [email protected] 2 F.I.Z.V. (Mammalogy), via Cleonia 30, I-00152 Rome, Italy. 3 Via Jevolella 2, Termini Imprese (PA), Italy. 4 Centre of Environmental Studies ‘Demetra’, via Tomassoni 17, I-61032 Fano (PU), Italy Abstract relationships, thus rendering the examination of the relationships between predators and prey an extreme- A field survey was conducted in a highly degraded barren en- ly complicated task for the ecologist (e.g., see Con- vironment in Sicily in order to investigate herpetofaunal com- nell, 1975; May, 1976; Schoener, 1986). However, munity composition and structure, habitat use (niche breadth and there is considerable literature (both theoretical and overlap) and relative abundance of a snake predator and two spe- empirical) indicating that case studies of extremely cies of lizard prey. The site was chosen because it has a simple community structure and thus there is potentially less ecological simple communities, together with the use of appropri- complexity to cloud any patterns observed. We found an unexpect- ate minimal models, can help us to understand the edly high overlap in habitat use between the two closely related basis of complex patterns of ecological relationships lizards that might be explained either by a high competition for among species (Thom, 1975; Arditi and Ginzburg, space or through predator-mediated co-existence i.e. -

Pressure Ulcer Staging Cards and Skin Inspection Opportunities.Indd

Pressure Ulcer Staging Pressure Ulcer Staging Suspected Deep Tissue Injury (sDTI): Purple or maroon localized area of discolored Suspected Deep Tissue Injury (sDTI): Purple or maroon localized area of discolored intact skin or blood-fi lled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure intact skin or blood-fi lled blister due to damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure and/or shear. The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, fi rm, mushy, boggy, and/or shear. The area may be preceded by tissue that is painful, fi rm, mushy, boggy, warmer or cooler as compared to adjacent tissue. warmer or cooler as compared to adjacent tissue. Stage 1: Intact skin with non- Stage 1: Intact skin with non- blanchable redness of a localized blanchable redness of a localized area usually over a bony prominence. area usually over a bony prominence. Darkly pigmented skin may not have Darkly pigmented skin may not have visible blanching; its color may differ visible blanching; its color may differ from surrounding area. from surrounding area. Stage 2: Partial thickness loss of Stage 2: Partial thickness loss of dermis presenting as a shallow open dermis presenting as a shallow open ulcer with a red pink wound bed, ulcer with a red pink wound bed, without slough. May also present as without slough. May also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum- an intact or open/ruptured serum- fi lled blister. fi lled blister. Stage 3: Full thickness tissue loss. Stage 3: Full thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible but Subcutaneous fat may be visible but bone, tendon or muscle are not exposed. -

WHO Guidance on Management of Snakebites

GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition GUIDELINES FOR THE MANAGEMENT OF SNAKEBITES 2nd Edition 1. 2. 3. 4. ISBN 978-92-9022- © World Health Organization 2016 2nd Edition All rights reserved. Requests for publications, or for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications, whether for sale or for noncommercial distribution, can be obtained from Publishing and Sales, World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia, Indraprastha Estate, Mahatma Gandhi Marg, New Delhi-110 002, India (fax: +91-11-23370197; e-mail: publications@ searo.who.int). The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising from its use. -

Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon

Journal of Book of Mormon Studies Volume 10 Number 2 Article 8 7-31-2001 Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon Andrew C. Skinner Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Skinner, Andrew C. (2001) "Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon," Journal of Book of Mormon Studies: Vol. 10 : No. 2 , Article 8. Available at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/jbms/vol10/iss2/8 This Feature Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Journals at BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Book of Mormon Studies by an authorized editor of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Title Serpent Symbols and Salvation in the Ancient Near East and the Book of Mormon Author(s) Andrew C. Skinner Reference Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 10/2 (2001): 42–55, 70–71. ISSN 1065-9366 (print), 2168-3158 (online) Abstract The serpent is often used to represent one of two things: Christ or Satan. This article synthesizes evi- dence from Egypt, Mesopotamia, Phoenicia, Greece, and Jerusalem to explain the reason for this duality. Many scholars suggest that the symbol of the serpent was used anciently to represent Jesus Christ but that Satan distorted the symbol, thereby creating this para- dox. The dual nature of the serpent is incorporated into the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the Book of Mormon. erpent ymbols & SSalvation in the ancient near east and the book of mormon andrew c. -

A Visual Guide to Identifying Cats

A Visual Guide to Identifying Cats When cats have similar colors and patterns, like two gray tabbies, it can seem impossible to tell them apart! That is, until you take note of even the smallest details in their appearance. Knowledge is power, whether you’re an animal control officer or animal Coat Length shelter employee who needs to identify cats regularly, or you want to identify your own cat. This guide covers cats’ traits from their overall looks, like coat pattern, to their tiniest features, like whisker color. Let’s use our office cats as examples: • Oliver (left): neutered male, shorthair, solid black, pale green eyes, black Hairless whiskers, a black nose, and black Hairless cats have no fur. paw pads. • Charles (right): neutered male, shorthair, brown mackerel tabby with spots toward his rear, yellow-green eyes, white whiskers with some black at the roots, a pink-brown nose, and black paw pads. Shorthair Shorthair cats have short fur across As you go through this guide, remember that certain patterns and markings the entire body. originated with specific breeds. However, these traits now appear in many cats because of random mating. This guide covers the following features: Coat Length ...............................................................................................3 Medium hair Coat Color ...................................................................................................4 Medium hair cats have longer fur around the mane, tail, and/or rear. Coat Patterns ..............................................................................................6 -

211356675.Pdf

306.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE STORERIA DEKA YI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. and western Honduras. There apparently is a hiatus along the Suwannee River Valley in northern Florida, and also a discontin• CHRISTMAN,STEVENP. 1982. Storeria dekayi uous distribution in Central America . • FOSSILRECORD. Auffenberg (1963) and Gut and Ray (1963) Storeria dekayi (Holbrook) recorded Storeria cf. dekayi from the Rancholabrean (pleisto• Brown snake cene) of Florida, and Holman (1962) listed S. cf. dekayi from the Rancholabrean of Texas. Storeria sp. is reported from the Ir• Coluber Dekayi Holbrook, "1836" (probably 1839):121. Type-lo• vingtonian and Rancholabrean of Kansas (Brattstrom, 1967), and cality, "Massachusetts, New York, Michigan, Louisiana"; the Rancholabrean of Virginia (Guilday, 1962), and Pennsylvania restricted by Trapido (1944) to "Massachusetts," and by (Guilday et al., 1964; Richmond, 1964). Schmidt (1953) to "Cambridge, Massachusetts." See Re• • PERTINENT LITERATURE. Trapido (1944) wrote the most marks. Only known syntype (Acad. Natur. Sci. Philadelphia complete account of the species. Subsequent taxonomic contri• 5832) designated lectotype by Trapido (1944) and erroneously butions have included: Neill (195Oa), who considered S. victa a referred to as holotype by Malnate (1971); adult female, col• lector, and date unknown (not examined by author). subspecies of dekayi, Anderson (1961), who resurrected Cope's C[oluber] ordinatus: Storer, 1839:223 (part). S. tropica, and Sabath and Sabath (1969), who returned tropica to subspecific status. Stuart (1954), Bleakney (1958), Savage (1966), Tropidonotus Dekayi: Holbrook, 1842 Vol. IV:53. Paulson (1968), and Christman (1980) reported on variation and Tropidonotus occipito-maculatus: Holbrook, 1842:55 (inserted ad- zoogeography. Other distributional reports include: Carr (1940), denda slip). -

Avoiding and Treating Timber Rattlesnake Bites Updated 2020

Avoiding and Treating Timber Rattlesnake Bites Updated 2020 Timber rattlesnakes live in the blufflands of southeastern Minnesota. They are not found anywhere else in the state. They can be distinguished from nonvenomous snakes by a pronounced off white rattle at the end of a black tail; by their head, which is solid brown/tan, triangular shaped, and noticeably larger than their slender neck; and by the dark, black bands or chevrons running across their body. The bands often resemble the black stripe on the cartoon character Charlie Brown’s shirt. The question that often arises when the word rattlesnake comes up is, “What if one bites me?” The likelihood of being bitten by a rattlesnake is quite small. Timber rattlesnakes are generally very docile snakes and typically bite as a last resort. Instead, its instincts are to avoid danger by retreating to cover or by hiding using its camouflage coloration to blend into its surroundings. If cornered and provoked, a timber rattlesnake may respond aggressively. It will usually rattle its tail to let you know it is getting agitated. The snake may even puff itself up to appear bigger. Upon further provocation, the snake may bluff strike, where it lunges out, but doesn’t open its mouth or it may strike with an open mouth. Because venom is costly for a rattlesnake to produce, and you are not considered food, a snake often will not actively inject venom when it bites. In fact, nearly half of all timber rattlesnake bites to humans contain little to no venom, commonly referred to as dry or medically insignificant bites. -

ISSN 2330-6025 SWCHR BULLETIN Published Quarterly by the SOUTHWESTERN CENTER for HERPETOLOGICAL RESEARCH (SWCHR) P.O

ISSN 2330-6025 SWCHR BULLETIN Published Quarterly by THE SOUTHWESTERN CENTER FOR HERPETOLOGICAL RESEARCH (SWCHR) P.O. Box 624 Seguin TX 78156 www.southwesternherp.com ISSN 2330-6025 OFFICERS 2010-2012 COMMITTEE CHAIRS PRESIDENT COMMITTEE ON COMMON AND Tom Lott SCIENTIFIC NAMES Tom Lott VICE PRESIDENT Todd Hughes RANGE MAP COMMITTEE Tom Lott SECRETARY AWARDS AND GRANTS COMMITTEE Diego Ortiz (vacant) EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR COMMUNICATIONS COMMITTEE Gerald Keown Gerald Keown BOARD MEMBERS ACTIVITIES AND EVENTS COMMITTEE Toby Brock Diego Ortiz Riley Campbell NOMINATIONS COMMITTEE Hans Koenig Gerald Keown EDITORIAL STAFF EDUCATION COMMITTEE (vacant) EDITOR Chris McMartin MEMBERSHIP COMMITTEE Toby Brock TECHNICAL EDITOR Linda Butler CONSERVATION COMMITTEE (vacant) ABOUT SWCHR Originally founded by Gerald Keown in 2007, SWCHR is a Texas non-profit association created under the provisions of the Texas Uniform Unincorporated Non-Profit Association Act, Chapter 252 of the Texas Business Organizations Code, governed by a board of directors and dedicated to promoting education of the Association’s members and the general public relating to the natural history, biology, taxonomy, conservation and preservation needs, field studies, and captive propagation of the herpetofauna indigenous to the American Southwest. SWCHR BULLETIN 1 Fall 2011 TABLE OF CONTENTS A Message from the President, Tom Lott . 2 Upcoming Event: Sanderson Snake Days . 3 Summary of July 17, 2011 Board Meeting, Gerald Keown . 4 TPWD Reptile & Amphibian Stamp FAQ, Scott Vaca . .6 Amended Texas Parks and Wildlife Code Pertaining to Reptiles and Amphibians, with Commentary by Dr. Andy Gluesenkamp. 8 An Annotated Checklist of the Snakes of Atascosa County, Texas, Tom Lott . 10 2011 Third Quarter Photographs of the Month . -

Myths Surrounding Snakes

MYTHS SURROUNDING SNAKES MYTH 1: Bites from baby venomous snakes are more dangerous than those from adults because they always deliver a full dose of venom. The legend goes that young snakes have not yet learned how to control the amount of venom they inject. They are therefore more dangerous than adult snakes, which will restrict the amount of venom they use in a bite or “dry bite”. This is simply untrue and all the evidence points towards bites from adults being more severe. Tests have shown that juvenile snakes can control their venom just as much as adults. Furthermore lets consider the following factors: adults have significantly larger fangs to deliver their venom and considerably more venom available than a juvenile. Therefore if a juvenile has venom glands only big enough to hold a 2ml of venom compared to an adult that can hold 30ml or more, then the bite from an adult will always have the potential to be more severe. I presume the reason this myth came into existence was to dissuade people from having a carefree attitude towards the potential dangers of a juvenile snake. The moral of the story is to treat every snake as a potentially dangerous and never expose your self to a situation where a snake of any size can bite you. MYTH 2: If you see a snake they’ll always be more Although it is possible to see more than one snake, for the most part this statement is untrue. Snakes are solitary animals for most of their lives so generally you will only ever encounter individuals. -

Common Species

Common Species on District Lands The Southwest Florida Water Management District (District) manages water resources in the west- central portion of Florida according to legislative mandates. The District uses public land acquisition funds to protect key lands for water resources. The natural communities, plants and animals on these lands also benefi t from a level of protection that can be experienced and enjoyed through recreational opportunities made available on District lands. Every year, approximately 2.5 million people visit the more than 436,000 acres of public conservation lands acquired by the District and its partners. The lands are open to the public for activities such as hiking, bicycling, hunting, horseback riding, fi shing, camping, picnicking and studying nature. The District provides these recreational opportunities so that residents may experience healthy natural communities. An array of natural landscapes is available from the meandering Outstanding Florida Southwest Florida Water Management District Waters riverine systems, the cypress domes and strands, swamps and hammocks, to the scrub, sandhill, and pine fl atwoods. The Common Species on District Lands brochure provides insight to what you may experience while recreating on public lands managed by the District. CONSERVATION LANDS Southwest Florida Water Management District Mammals Southwest Florida Water Management District iStock W Barbour - Smithsonian Institute Roger Virginia Brazilian Opossum Free-Tailed Bat Didelphis virginiana Tadarida brasiliensis iStock Ivy