Rethinking Rembrandt's Renaissance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520)

The Italian High Renaissance (Florence and Rome, 1495-1520) The Artist as Universal Man and Individual Genius By Susan Behrends Frank, Ph.D. Associate Curator for Research The Phillips Collection What are the new ideas behind the Italian High Renaissance? • Commitment to monumental interpretation of form with the human figure at center stage • Integration of form and space; figures actually occupy space • New medium of oil allows for new concept of luminosity as light and shadow (chiaroscuro) in a manner that allows form to be constructed in space in a new way • Physiological aspect of man developed • Psychological aspect of man explored • Forms in action • Dynamic interrelationship of the parts to the whole • New conception of the artist as the universal man and individual genius who is creative in multiple disciplines Michelangelo The Artists of the Italian High Renaissance Considered Universal Men and Individual Geniuses Raphael- Self-Portrait Leonardo da Vinci- Self-Portrait Michelangelo- Pietà- 1498-1500 St. Peter’s, Rome Leonardo da Vinci- Mona Lisa (Lisa Gherardinidi Franceso del Giacondo) Raphael- Sistine Madonna- 1513 begun c. 1503 Gemäldegalerie, Dresden Louvre, Paris Leonardo’s Notebooks Sketches of Plants Sketches of Cats Leonardo’s Notebooks Bird’s Eye View of Chiana Valley, showing Arezzo, Cortona, Perugia, and Siena- c. 1502-1503 Storm Breaking Over a Valley- c. 1500 Sketch over the Arno Valley (Landscape with River/Paesaggio con fiume)- 1473 Leonardo’s Notebooks Studies of Water Drawing of a Man’s Head Deluge- c. 1511-12 Leonardo’s Notebooks Detail of Tank Sketches of Tanks and Chariots Leonardo’s Notebooks Flying Machine/Helicopter Miscellaneous studies of different gears and mechanisms Bat wing with proportions Leonardo’s Notebooks Vitruvian Man- c. -

Baldassare Castiglione's Love and Ideal Conduct

Chapter 1 Baldassare Castiglione’s B OOK OF THE COURTIER: Love and Ideal Conduct Baldassare Castiglione’s Book of the Courtier was quite possibly the single most popular secular book in sixteenth century Europe, pub- lished in dozens of editions in all major European languages. The Courtier is a complex text that has many reasons for its vast popular- ity. Over the years it has been read as a guide to courtly conduct, a meditation on the nature of service, a celebration of an elite com- munity, a reflection on power and subjection, a manual on self- fashioning, and much else besides. But The Courtier must also be seen as a book about love. The debates about love in The Courtier are not tangential to the main concerns of the text; they are funda- mental to it. To understand the impact of The Courtier on discourses of love, one must place the text’s debates about love in the context of the Platonic ideas promulgated by Ficino, Bembo, and others, as well as the practical realities of sexual and identity politics in early modern European society. Castiglione’s dialogue attempts to define the perfect Courtier, but this ideal figure of masculine self-control is threatened by the instability of romantic love. Castiglione has Pietro Bembo end the book’s debates with a praise of Platonic love that attempts to redefine love as empowering rather than debasing, a practice of self-fulfillment rather than subjection. Castiglione’s Bembo defines love as a solitary pursuit, and rejects the social in favor of the individual. -

Raphael's Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione (1514-16) in the Context of Il Cortegiano

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Paragon/Paragone: Raphael's Portrait of Baldassare Castiglione (1514-16) in the Context of Il Cortegiano Margaret Ann Southwick Virginia Commonwealth University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd Part of the Arts and Humanities Commons © The Author Downloaded from https://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/etd/1547 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. O Margaret Ann Southwick 2005 All Rights Reserved PARAGONIPARAGONE: RAPHAEL'S PORTRAIT OF BALDASSARE CASTIGLIONE (1 5 14-16) IN THE CONTEXT OF IL CORTEGIANO A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at Virginia Cornmonwealtli University. MARGARET ANN SOUTHWICK M.S.L.S., The Catholic University of America, 1974 B.A., Caldwell College, 1968 Director: Dr. Fredrika Jacobs Professor, Department of Art History Virginia Commonwealth University Richmond, Virginia December 2005 Acknowledgenients I would like to thank the faculty of the Department of Art History for their encouragement in pursuit of my dream, especially: Dr. Fredrika Jacobs, Director of my thesis, who helped to clarify both my thoughts and my writing; Dr. Michael Schreffler, my reader, in whose classroom I first learned to "do" art history; and, Dr. Eric Garberson, Director of Graduate Studies, who talked me out of writer's block and into action. -

Olga Zorzi Pugliese Castiglione's the Book of the Courtier (Il Libro Del

138 Book Reviews Olga Zorzi Pugliese Castiglione’s The Book of the Courtier (Il Libro del Cortegiano): A Classic in the Making Viaggio d’Europa 10. Naples: Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, 2008. Pp 382. The five extant manuscripts of Baldassare Castiglione’s Libro del Cortegiano, docu- menting what Olga Zorzi Pugliese terms his “propensity for endless revision,” offer an unique opportunity to trace the stylistic and ideological development of one of the most influential books of the entire early modern period. For the fifteen years prior to its publication in 1528, as Castiglione’s own career path intersected with the trajectory of the crises of the Italian peninsula that culminated in the Sack of Rome, the courtier and diplomat continuously rewrote his ambitious treatise. An invaluable addition to Amadeo Quondam’s recent work on the textual history of the Cortegiano, Pugliese’s stimulating monograph is the fruit of a research project that exploited modern database technology to collate and search all five manuscripts. The extent of the divergences between consecutive drafts, a corollary of the manner in which Castiglione excised, shifted, revised, and reinstated individual passages over a series of manuscripts, has made it difficult for past scholars to track the complexity of his writing process. Vittorio Cian established the basic chronological order of the manu- scripts in the first half of the twentieth century, but the identification and analysis of specific variants remain an ongoing concern. Given the limited access provided by Castiglione’s descendants in Mantua to the autograph material in the family archive, comprising fragments of the first draft, the starting point of most contemporary criti- cism has been Ghino Ghinassi’s 1968 edition of the so-called seconda redazione that records the intermediate stage in the evolution of the treatise. -

III. RAPHAEL (1483-1520) Biographical and Background Information 1. Raffaello Santi Born in Urbino, Then a Small but Important C

III. RAPHAEL (1483-1520) Biographical and background information 1. Raffaello Santi born in Urbino, then a small but important cultural center of the Italian Renaissance; trained by his father, Giovanni Santi. 2. Influenced by Perugino, Leonardo da Vinci, and Michelangelo; worked in Florence 1504-08, in Rome 1508-20, where his chief patrons were Popes Julius II and Leo X. 3. Pictorial structures and concepts: the picture plane, linear and atmospheric perspective, foreshortening, chiaroscuro, contrapposto. 4. Painting media a. Tempera (egg binder and pigment) or oil (usually linseed oil as binder); support: wood panel (prepared with gesso ground) or canvas. b. Fresco (painting on wet plaster); cartoon, pouncing, giornata. Selected works 5. Religious subjects a. Marriage of the Virgin (“Spozalizio”), 1504 (oil on roundheaded panel, 5’7” x 3’10”, Pinacoteca de Brera, Milan) b. Madonna of the Meadow, c. 1505 (oil on panel, 44.5” x 34.6”, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna) c. Madonna del Cardellino (“Madonna of the Goldfinch”), 1506 (oil on panel, 3’5” x 2’5”, Uffizi Gallery, Florence) d. Virgin and Child with St. Sixtus and St. Barbara (“Sistine Madonna”), 1512-13 (oil on canvas, 8’8” x 6’5”, Gemäldegalerie, Dresden) 6. Portraits a. Agnolo Doni, c.1506 (oil on panel, 2’ ¾” x 1’5 ¾”, Pitti Palace, Florence) b. Maddalena Doni, c.1506 (oil on panel, 2’ ¾” x 1’5 ¾”, Pitti Palace, Florence) c. Cardinal Tommaso Inghirami, c. 1510-14 (oil on panel, 2’11 ¼” x 2’, Pitti Palace, Florence) d. Baldassare Castiglione, c. 1514-15 (oil on canvas, 2’8” x 2’2”, Louvre Museum, Paris) e. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Culturele ondernemers in de Gouden Eeuw: De artistieke en sociaal- economische strategieën van Jacob Backer, Govert Flinck, Ferdinand Bol en Joachim von Sandrart Kok, E.E. Publication date 2013 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Kok, E. E. (2013). Culturele ondernemers in de Gouden Eeuw: De artistieke en sociaal- economische strategieën van Jacob Backer, Govert Flinck, Ferdinand Bol en Joachim von Sandrart. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:03 Oct 2021 Summary Jacob Backer (1608/9-1651), Govert Flinck (1615-1660), Ferdinand Bol (1616-1680), and Joachim von Sandrart (1606-1688) belong among the most successful portrait and history painters of the Golden Age in Amsterdam. -

Webfile121848.Pdf

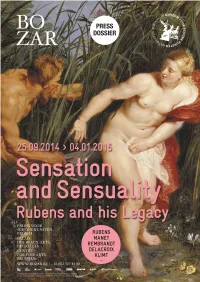

0 TABLE OF CONTENTS Press release ................................................................................................................................................... 2 Catalogue text: Nico Van Hout - Curator ...................................................................................................... 6 Gallery texts ................................................................................................................................................... 11 Transversal Activities ................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR MUSIC ......................................................................................................................................... 14 BOZAR LITERATURE ............................................................................................................................. 17 BOZAR EXPO ........................................................................................................................................... 17 BOZAR CINEMA ...................................................................................................................................... 18 Rubens for families ...................................................................................................................................... 19 Disovery trails for families (6>12) ........................................................................................................... 19 -

Honthorst, Gerrit Van Also Known As Honthorst, Gerard Van Gherardo Della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656

National Gallery of Art NATIONAL GALLERY OF ART ONLINE EDITIONS Dutch Paintings of the Seventeenth Century Honthorst, Gerrit van Also known as Honthorst, Gerard van Gherardo della Notte Dutch, 1592 - 1656 BIOGRAPHY Gerrit van Honthorst was born in Utrecht in 1592 to a large Catholic family. His father, Herman van Honthorst, was a tapestry designer and a founding member of the Utrecht Guild of St. Luke in 1611. After training with the Utrecht painter Abraham Bloemaert (1566–1651), Honthorst traveled to Rome, where he is first documented in 1616.[1] Honthorst’s trip to Rome had an indelible impact on his painting style. In particular, Honthorst looked to the radical stylistic and thematic innovations of Caravaggio (Roman, 1571 - 1610), adopting the Italian painter’s realism, dramatic chiaroscuro lighting, bold colors, and cropped compositions. Honthorst’s distinctive nocturnal settings and artificial lighting effects attracted commissions from prominent patrons such as Cardinal Scipione Borghese (1577–1633), Cosimo II, the Grand Duke of Tuscany (1590–1621), and the Marcheses Benedetto and Vincenzo Giustiniani (1554–1621 and 1564–1637). He lived for a time in the Palazzo Giustiniani in Rome, where he would have seen paintings by Caravaggio, and works by Annibale Carracci (Bolognese, 1560 - 1609) and Domenichino (1581–-1641), artists whose classicizing tendencies would also inform Honthorst’s style. The contemporary Italian art critic Giulio Mancini noted that Honthorst was able to command high prices for his striking paintings, which decorated -

The Ideal of the Well-Rounded Man by Castiglione

World History – Kelemen The Ideal of the Well-Rounded Man by Castiglione The Greeks believed that a man ought to be “well-rounded” meaning that he should develop every aspect of his personality. Count Baldassare Castiglione, a sixteenth-century Italian diplomat, combined this ideal with new Renaissance ideals in a book called The Courtier. As the title implies, Castiglione was writing for the people in the courts of the nobility, but his ideas did influence the middle class merchants and craftsmen. For this evening's game, let us select someone to portray a perfect courtier. Characteristics of a He should explain all of the conditions and special qualities that a courtier Renaissance Man must have; if he mentions something that is not correct, anyone may correct him… Since doing the same thing over and over again is tiresome, we must vary out life with different occupations. For this reason, I would have our courtier sometimes take part in quiet and peaceful exercises. If he is to escape envy and appear agreeable to everyone, the courtier should join others in what they are doing. Yet he should always be careful to do those things that are praiseworthy. He must use good judgment to see that he never appears foolish. But let him laugh, joke, banter, frolic, and dance, yet in such a way that he shall always appear genial and discreet. And in whatever he does or says, let him do it with grace. I would have the courtier know literature, in particular those studies known as the humanities. He should be able to speak not only Latin but Greek, as well. -

Information to Users

INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy subm itted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs included in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6’ x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI directly to order. ProQuest Information and Learning 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. NOTE TO USERS Copyrighted materials in this document have not been filmed at the request of the author. They are available for consultation at the author’s university library. -

New Patterns of Renaissance Thought: Secularism and Humanism

World History – Kelemen New Patterns of Renaissance Thought: Secularism and Humanism The word Renaissance means "rebirth." Historically, it refers to a time in Western civilization from about 1400 to 1600 that was characterized by the revival of three things: international commerce, interest in Classical ideas, and a belief in the potential of human achievement. For reasons that are both geographical and social, the Renaissance began in Italy where renewed trade with the East flowed into Europe via the Mediterranean Sea and, therefore, through the Italian peninsula. The Italian Renaissance flowered until, as a result of invasions from France and Great Britain, Renaissance ideals flowed into the rest of Western Europe. The main themes at the heart of the Renaissance, secularism and humanism, had significant impacts on Western Civilization. Secularism comes from the word secular, meaning “of this world”. Before the Renaissance, medieval Christian civilization had been largely concerned with faith and salvation in the afterlife. The new economic and political opportunities opening up for Western Europe in the Late Middle Ages encouraged more people to take an interest in life in this world. During the Renaissance, people started to see life on Earth as worth living for its own sake, not just as an ordeal to endure before going to heaven. The art of the period in particular exhibited this secular spirit, showing detailed and accurate scenery, anatomy, and nature. Medieval artists generally ignored such realistic aspects in their paintings which focused only on the glory of God. This is not to say that Renaissance people had lost faith in God. -

Barbarigo' by Titian in the National Gallery, London

MA.JAN.MAZZOTTA.pg.proof.corrs_Layout 1 08/12/2011 15:31 Page 12 A ‘gentiluomo da Ca’ Barbarigo’ by Titian in the National Gallery, London by ANTONIO MAZZOTTA ‘AT THE TIME he first began to paint like Giorgione, when he was no more than eighteen, [Titian] made the portrait of a gen- tleman of the Barbarigo family, a friend of his, which was held to be extremely fine, for the representation of the flesh-colour was true and realistic and the hairs were so well distinguished one from the other that they might have been counted, as might the stitches in a doublet of silvered satin which also appeared in that work. In short the picture was thought to show great diligence and to be very successful. Titian signed it in the shadow, but if he had not done so, it would have been taken for Giorgione’s work. Meanwhile, after Giorgione himself had executed the principal façade of the Fondaco de’ Tedeschi, Titian, through Barbarigo’s intervention, was commissioned to paint certain scenes for the same building, above the Merceria’.1 Vasari’s evocative and detailed description, which would seem to be the result of seeing the painting in the flesh, led Jean Paul Richter in 1895 to believe that it could be identified with Titian’s Portrait of a man then in the collection of the Earl of Darnley at Cobham Hall and now in the National Gallery, London (Fig.15).2 Up to that date it was famous as ‘Titian’s Ariosto’, a confusion that, as we shall see, had been born in the seventeenth century.