Utku Ali Riza Alpaydin.Pdf (1.050Mb)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Drug and Alcohol Dependence 202 (2019) 87–92

Drug and Alcohol Dependence 202 (2019) 87–92 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Drug and Alcohol Dependence journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/drugalcdep Evidence for essential unidimensionality of AUDIT and measurement invariance across gender, age and education. Results from the WIRUS study T ⁎ Jens Christoffer Skogena,b,c, , Mikkel Magnus Thørrisend, Espen Olsene, Morten Hessef, Randi Wågø Aasc,d a Department of Health Promotion, Norwegian Institute of Public Health, Bergen, Norway b Alcohol & Drug Research Western Norway, Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger, Norway c Department of Public Health, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway d Department of Occupational Therapy, Prosthetics and Orthotics, Faculty of Health Sciences, OsloMet – Oslo Metropolitan University, Oslo, Norway e UiS Business School, University of Stavanger, Stavanger, Norway f Centre for Alcohol and Drug Research, Aarhus University, Denmark ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Introduction: Globally, alcohol use is among the most important risk factors related to burden of disease, and Alcohol screening commonly emerges among the ten most important factors. Also, alcohol use disorders are major contributors to AUDIT global burden of disease. Therefore, accurate measurement of alcohol use and alcohol-related problems is im- Factor analysis portant in a public health perspective. The Alcohol Use Identification Test (AUDIT) is a widely used, brief ten- Measurement invariance item screening instrument to detect alcohol use disorder. Despite this the factor structure and comparability Work life across different (sub)-populations has yet to be determined. Our aim was to investigate the factor structure of the Sociodemographics AUDIT-questionnaire and the viability of specific factors, as well as assessing measurement invariance across gender, age and educational level. -

Pinchbet / Spreadsheet 2015 - 2017 (24 March '15 - 31 January '17) ROI TOT.: 5.9 % B TOT.: 6,520 TOT

ROI October '16: 9.27% (398 bets), ROI November '16: -4.22% (688 bets), ROI December '16: 2.11% (381bets), ROI January 2.11% (565bets) '16: -1.05% (688bets), ROI December (398bets),-4.22% '17: ROI November 9.27% '16: '16: ROI October (283bets) -3.0% '16: (262bets), ROI September (347bets), 3.10% ROI August 6.39% (405bets), ROI July'16: 6.9% (366bets),'16: ROI JuneROI May 0.5% '16: '16: (219bets), ROI January 4.9% (642bets), ROI February '15: 7.8% (460bets) ROI December (512bets), ROI March (325bets), 0.9% ROI April-6.1% 1.4% '16: '16: '16: (323bets) (269bets), 8.5% ROI November 9.6% '15: '15: (386bets), ROI October 4.1% '15: (337bets), ROI September ROI August7.5% '15: (334bets) 24% (72 bets), ROI July 2.7% (304bets), '15: (227bets), ROI June (49ROI MayROI March9.9% bets), ROI April0.4% '15: 20.3% '15: '15: '15: ROI TOT.: 5.9 % BROI DAY:TOT.: 5.9 % EUR / 11.1 AVG. B 6,153 TOT.: 6,520 TOT.RETURN: PinchBet / SpreadSheet 2015 - 2017 PinchBet - 2017 / SpreadSheet 2015 1000 2000 3000 4000 5000 6000 7000 0 1 228 455 682 909 1136 1363 1590 1817 2044 2271 '17) January - 31 March'15 (24 2498 2725 2952 3179 3406 3633 3860 Return (EUR) Return 4087 4314 4541 4768 4995 5222 5449 5676 5903 6130 6357 6584 6811 7038 7265 7492 7719 7946 Trend line Return (EUR) No. Bets Return (EUR) January '17 January '17 December '16 December '16 November '16 November '16 October '16 October '16 September '16 September '16 August '16 August '16 July '16 July '16 June '16 June '16 May '16 May '16 April '16 April '16 March '16 March'16 February '16 February '16 No. -

The Bologna Process and Heis Institutional Autonomy

Athens Journal of Education - Volume 7, Issue 4, November 2020 – Pages 364-384 The Bologna Process and HEIs Institutional Autonomy By Linda Helén Haukland The Bologna Process has made a strong impact on the development of European higher education, although the greatest impact has not been from the process itself, but from the national reforms introduced along with it. With a relatively young higher education system, Norway was ahead of most European countries in implementing the Bologna Process and reforms indirectly linked to it. Due to path dependencies and the Higher Education Institutions being, to a certain extent, autonomous and carriers of their own culture, we cannot draw conclusions at the local level without empirical studies. Therefore, the case of Nord University shows us how this process directly and indirectly affected Higher Education Institutions in Norway. The Higher Education Institutions (HEI) integrated horizontally in an education system that was increasingly hierarchical and competitive. The need for standardisation in order to secure equality and efficiency, and the demand for greater autonomy in the HEIs was answered by strengthening some and weakening other forms of institutional autonomy along with the establishment of a new accreditation system. Three dimensions of autonomy are touched on in this study. Firstly, the question of who has decision-making power in the HEIs defines whether they are ruled by professional or administrative autonomy. Secondly, the question of the HEIs’ mission is decided either by the HEI itself, representing substantive autonomy, or by external demands on production and external funding, representing what I call beneficial autonomy. Finally, the question of how the HEIs fulfil their mission decides whether they have individual autonomy or procedural autonomy. -

Fragmentering Eller Mobilisering? Regional Utvikling I Nordvest Er Temaet for Denne Antologien Basert På Artikler Presentert På Fjordkonferansen 2014

Regional utvikling i Nordvest Fragmentering eller mobilisering? Regional utvikling i Nordvest er temaet for denne antologien basert på artikler presentert på Fjordkonferansen 2014. Mye har endret seg på Nordvestlandet det siste året, og forslag til flere større regionalpolitiske reformer skaper stort engasjement og intens debatt. Blant annet gjelder dette områder knyttet til samarbeid, koordinering og sammenslåinger Fragmentering eller mobilisering? av politidistrikt, byer og tettsteder, høyskoler og sykehus. Parallelt med disse politiske endringene har en halvering av oljeprisen og stenging av viktige eksportmarkeder for fisk gitt skremmeskudd til næringslivet Regional utvikling i Nordvest i regionen. Dette gjør at innovasjonsevnen blir enda viktigere i tiden framover. Viktige hindringer for innovasjon i regionale Fjordantologien 2014 innovasjonssystem kan være fragmentering (mangel på samarbeid og koordinering), «lock-in» (manglende læringsevne) og «institutional thinness» (mangel på spesialiserte kunnskapsaktører).Det er derfor Redaktørar: all grunn til å stille seg spørsmålet om hvilken retning utvikling Øyvind Strand på Nordvestlandet tar: går det mot regional fragmentering eller Erik Nesset regional mobilisering? Er Nordvestlandet fremdeles «liv laga»? Disse Harald Yndestad spørsmålene blir reist både direkte og indirekte i mange av artiklene i årets antologi. Fokuset for Fjordkonferansen er faglig utvikling med mottoet «av fagfolk for fagfolk». Formålet er å være en arena for utveksling av kunnskap og erfaringer, bidra til nettverksbygging mellom fagmiljøene i regionen og stimulere til økt publisering av vitenskapelige artikler fra kunnskapsinstitusjonene i Sogn og Fjordane og Møre og Romsdal. Fjordantologien 2014 Fjordantologien Fjordkonferansen ble arrangert i Loen 19. – 20. juni 2014, med regional utvikling som det samlende temaet. Det var 29 foredrag på programmet, og av disse hadde 26 en forskningbasert karakter. -

Kvæfjord Og Tjeldsund

PROGRAM FOR MARKERING AV VERDENSUKEN FOR PSYKISK HELSE I HARSTAD, KVÆFJORD OG TJELDSUND 28. sept. – 16. oktober 2020 SPØR MER Verdensdagen for psykisk helse er Norges største opplysningskampanje for psykisk helse 10. oktober. Velkommen til markering av verdensdagen for psykisk helse 2020 Årets tema er ”Spør Mer” «Spør mer» er tema 2 under paraplyen «Oppmerksomhet og tilstedeværelse». I 2019 har vi jobbet med «Gi tid» hvor vi oppfordret folk til å gi tid til seg selv og til hverandre. La oss bruke 2020 til å bruke denne tiden til å vise interesse for hverandre. God psykisk helse starter med gode relasjoner. Gode relasjoner bygges over tid og gjennom felleskap, åpenhet, respekt og nysgjerrighet. Hvis du ønsker informasjon eller opplysninger om verdensdagsmarkeringen, kan du ta kontakt med oss. Bikuben/LPP koordinator ved VD: Ann-Kirsti Brustad Tlf: 90 89 87 88 [email protected] Alle aktivitetene er gratis. Ta med familie, venner og bekjente og benytt deg av de mange ulike og interessante arrangementene. Vi ønsker lykke til med gjennomføring av alle årets Verdensdagsarrangementer. Arbeidsgruppa Verdensdagen Harstad Ann-Kirsti Brustad Bikuben/LPP, Synnøve Larsen Bikuben, Lena kristin Madsen Fontenehuset, Viktor Brustad Mental Helse Kvæfjord, Kristoffer Rubach Biblioteket Harstad kommune, Geir Skjalmar Stedet Frelsesarmeen, Kirsti Valvik Olsen Mental Helse Harstad #Spør Alle har behov for å bli sett. Det å bli sett gir en følelse av å høre til og være viktig. Tilhørighet er grunnleggende for god psykisk helse. Det å vise interesse for et annet menneske er å gi oppmerksomhet og kan ha en positiv effekt på det mennesket. På jobben, i nabolaget, mellom venner, familie eller til og med tilfeldige medpassasjerer. -

Peab's Annual and Sustainability Report 2016

Annual and Sustainability Report 2016 A LOCALLY ENGAGED COMMUNITY BUILDER Content 2016 in summary 1 Comments from the CEO 2–3 External circumstances and the market 4–5 Goals and strategies 6–9 Market summary – Peab’s business areas 10–11 Peab’s take on sus- P21 Our take on sustainable operations 12–35 tainable operations Attitude The Employees 16–21 changing The Business 22–25 Five initiatives that reflect our work with workshops sustainability in the focus areas The Climate and Environment 26–31 Employees, The Business, Climate and Environment and Social Engagement. Social Engagement 32–35 Board of Directors' report 36–56 The Group 36–39 Business area Construction 40–41 Business area Civil Engineering 42–43 Business area Industry 44–45 P24 P28 Business area Project Development 46–49 Everything Peab’s ECO- Risks and risk management 50–52 in order Asfalt – a better Other information and appropriation of profit 53–56 choice for the Financial reports and notes 57–109 environment Auditor's report 110–113 Corporate governance 114–117 Board of Directors 118 Executive management and auditor 119 The Peab share 120–121 Five-year overview 122 Alternative performance measures P31 P33 and definitions 123 Forward-looking The Peab School About the sustainability report 124 neighborhood with trains young Global Compact principles 124 a strong environ- immigrants mental profile Active memberships 125 GRI Index 126–127 Annual General Meeting 128 Shareholder information 128 Formal annual and Group financial reports which have been audited by company accountants, pages 36–109. Peab AB is a public company, Company ID 556061-4330. -

THE YEAR 2015 NORWEGIAN AGENCY for QUALITY ASSURANCE in EDUCATION D E a R READER Terje Mørland Director General

NOKUT THE YEAR 2015 NORWEGIAN AGENCY FOR QUALITY ASSURANCE IN EDUCATION D E A R READER Terje Mørland Director General Finding a balance between a focus on education programmes. This is part of people who have studied abroad can excellence and a broad approach is a well- NOKUT’s development work, and it will use their qualifications in the Norwegian known problem for research initiatives, be completely separate from the accred- labour market. As the national resource though somewhat less so for education. itation process. The group is expected to centre for foreign education, we provide On several occasion in 2015, we expressed come up with activities and measures to employers and educational institutions our belief that it is high time that the focus stimulate innovation and raise competence. with advice and information about the on excellent research was also accompa- Norwegian recognition schemes through nied by a focus on excellence in education. Everyone shall be happy with the quality our turbo evaluation schemes. There will The signals and funding received from the of education at the institution they are probably be a growing need for this in Ministry of Education and Research for a studying at, be it a college of tertiary voca- the time ahead. new call for applications for Centres of tional education, a university college or a Excellence in Higher Education indicate university. In order to map the status in Many immigrants arrived in Norway in a growing focus on excellence in educa- this area, we have in recent years shifted 2015, and the number of applications for tion. -

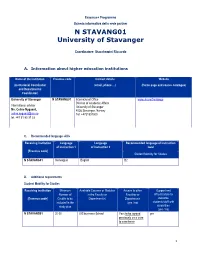

N STAVANG01 University of Stavanger

Erasmus+ Programme Scheda informativa della sede partner N STAVANG01 University of Stavanger Coordinatore: Stacchezzini Riccardo A. Information about higher education institutions Name of the institution Erasmus code Contact details Website (Institutional Coordinator (email, phone …) (Home page and course catalogue) and Departmental Coordinator) University of Stavanger N STAVANG01 International Office www.uis.no/frontpage Division of Academic Affairs International advisor University of Stavanger Ms. Celine Nygaard, 4036 Stavanger. Norway [email protected] Tel. +4751831000 tel. +47 51 83 37 33 C. Recommended language skills Receiving institution Language Language Recommended language of instruction of instruction 1 of instruction 2 level [Erasmus code] Student Mobility for Studies N STAVANG01 Norwegian English B2 D. Additional requirements Student Mobility for Studies Receiving institution Minimum Available Courses or Modules Access to other Support and Number of in the Faculty or Faculties or infrastructure to [Erasmus code] Credits to be Department(s) Departments welcome included in the (yes / no) students/staff with study plan disabilities (yes / no) N STAVANG01 20-30 UIS business School Yes (to be agreed yes previously on a case to case basis 1 N STAVANG01 For information on UiS’ services for mobile participants with special needs/disabilities, please see this web page: http://www.uis.no/studies/practical-information/additional-needs/ E. Calendar Receiving Autumn term Spring term institution APPLICATION DEADLINE APPLICATION DEADLINE -

Faculty for Biosciences and Aquaculture Annual Report 2016

FACULTY FOR BIOSCIENCES AND AQUACULTURE ANNUAL REPORT 2016 We educate for the future! MILESTONES IN 2016 NEW UNIVERSITY FIRST CLASS TO GRADUATE AS DOCTORS Nord University was established on 1 January 2016 as OF VETERINARY MEDICINE AT UVMP a result of a merger between the former University of The cooperation with the University of Veterinary Nordland, Nesna University College and Nord-Trøn- Medicine and Pharmacy (UVMP) in Slovakia is part of delag University College. It was a big milestone. The FBA’s international profile. The joint degree of Joint Board adopted a new faculty structure with five Bachelor in Animal Science constitutes the corner- faculties in June 2016. The “old FBA” in Bodø and stone of the cooperation. The first 11 veterinarians the “green” sectors in animal science and nature graduated in 2016. They started their studies in Bodø management at Steinkjer became a new Faculty of in 2010 and completed their bachelor’s degree in Biosciences and Aquaculture (FBA). Formally, the 2013. In June 2016 they got their degree in veteri- new faculty was established on 1.1.2017, and gave nary medicine, and were ready to start practice in FBA a solid growth both in number of employees Norway or other countries they wish to work. All and students. graduates had relevant work to go to the day they received their diploma. In the coming years, this Several processes and meetings among new collea- cooperation between FBA and UVMP, with study gues were carried out at both university and faculty starting in Bodø, will educate ± 25 veterinarians - a level during 2016. -

Norsk Bokfortegnelse / Norwegian National Bibliography Nyhetsliste / List of New Books

NORSK BOKFORTEGNELSE / NORWEGIAN NATIONAL BIBLIOGRAPHY NYHETSLISTE / LIST OF NEW BOOKS Utarbeidet ved Nasjonalbiblioteket Published by The National Library of Norway 2015: 06 : 1 Alfabetisk liste / Alphabetical bibliography Registreringsdato / Date of registration: 2015.06.01-2015.06.14 100 inspirerende mønster til å fargelegge selv Dahlström, Pontus, 1970- Kreativitet og mindfulness : fargelegging som gir ro i sjelen / [idé og prosjektledelse: Alexandra Lidén ; formgivning, billedresearch og billedbearbeiding: Eric Thunfors ; tekst: Pontus Dahlström]. - [Oslo] : Cappelen Damm faktum, 2015. - 2 b. : ill. ; 26 cm. Originaltittel: Kreativitet och mindfulness. - 100 inspirerende mønster til å fargelegge selv. 2015. - [118] s. Originaltittel: 100 bilder på inspirerande mönster att färglägga själv. ISBN 978-82-02-48360-9 (ib.) Dewey: 100 mønstre av planter og dyr til å fargelegge selv Dahlström, Pontus, 1970- Kreativitet og mindfulness : fargelegging som gir ro i sjelen / [idé og prosjektledelse: Alexandra Lidén ; formgivning, billedresearch og billedbearbeiding: Eric Thunfors ; tekst: Pontus Dahlström]. - [Oslo] : Cappelen Damm faktum, 2015. - 2 b. : ill. ; 26 cm. Originaltittel: Kreativitet och mindfulness. - 100 mønstre av planter og dyr til å fargelegge selv. 2015. - [120] s. Originaltittel: 100 bilder på växter och djur att färglägga själv. ISBN 978-82-02-48366-1 (ib.) Dewey: [5. trinn] Salto / [bilderedaktør: Kari Anne Hoen]. - Bokmål[utg.]. - [Oslo] : Gyldendal undervisning, 2013- . - b. : ill. Norsk for barnetrinnet. - [5. trinn] / Marianne Teigen ... [et al.]. 2015- . - b. Tittel laget av katalogisator. Dewey: [6. trinn] Ordriket 1-7 / Christian Bjerke ... [et al.]. - Nynorsk[utg.]. - Bergen : Fagbokforl., 2013- . - b. : ill. For lærerveiledninger, se bokmålutg. Tittel hentet fra omslaget. Dewey: 1 Abdel-Samad, Hamed 1972-: Den islamske fascismen Abdel-Samad, Hamed, 1972- Den islamske fascismen / Hamed Abdel-Samad ; oversatt av Lars Rasmussen Brinth og Christian Skaug. -

Dato: 09.09.2021 Sted: Bodø

Dato: 09.09.2021 Sted: Bodø Øyvind Fylling-Jensen styreleder Anders Söderholm medlem Lise Dahl Karlsen medlem Eva Maria Kristoffersen medlem Ellen Sæthre-McGuirk medlem Oddbjørn Johansen medlem Elisabeth Suzen medlem Tone Elisabeth Berg medlem Sissel Marit Jensen medlem Synne Witzø medlem Tord Apalvik medlem Øyvind Fylling-Jensen styreleder 1 Saksliste Vedtakssaker 62/21 Styrets konstituering og oppnevning av nestleder 3 63/21 Godkjenning av protokoll fra møtet 10.-11. juni 11 64/21 Rektor rapporterer 9. september 31 65/21 Forretningsorden for styret ved Nord universitet 32 66/21 Instruks for rektor ved Nord universitet 37 67/21 Delegasjonsreglement 2021 41 68/21 Budsjettforslag 2023 - Satsing utenfor rammen 51 69/21 Oppfølging av etatsstyring 2021 67 70/21 Statusrapport for forskning ved Nord universitet, 2020 75 71/21 Høringsinnspill til Langtidsplan for forskning og høyere utdanning, 2021 83 72/21 Klagenemndas årsrapport 2020 97 73/21 Lokale lønnsforhandlinger - 2021 107 74/21 Internrevisjon 2022, forslag til tema 111 75/21 Møteplan for styret for Nord universitet 2022 114 76/21 Langtidsorden 9. september 115 77/21 Referater 9. september 117 2 62/21 Styrets konstituering og oppnevning av nestleder - 21/00120-6 Styrets konstituering og oppnevning av nestleder : Styrets konstituering og oppnevning av nestleder Arkivsak-dok. 21/00120-6 Saksansvarlig Hanne Solheim Hansen Saksbehandler Linda Therese Kristiansen Møtedato 09.09.2021 STYRETS KONSTITUERING OG OPPNEVNING AV NESTLEDER Forslag til vedtak: Styret for Nord universitet konstitueres og oppnevner Anders Söderholm som styrets nestleder i perioden 01.08.2021 – 31.07.2025. 3 62/21 Styrets konstituering og oppnevning av nestleder - 21/00120-6 Styrets konstituering og oppnevning av nestleder : Styrets konstituering og oppnevning av nestleder Saksframstilling Nord universitets styresammensetning er regulert av Lov om universiteter og høyskoler (UH- loven) § 9-3. -

Annual and Sustainability Report 2019

Peab Annual and Sustainability Report 2019 Report Annual and Sustainability Peab Annual and Sustainability Report 2019 LOCALLY ENGAGED COMMUNITY BUILDER The Nordic Community Builder Peab is one of the leading construction and civil engineering companies in the Nordic area with operations in Sweden, Norway and Finland. Peab affects society and the environment for the Peab’s business contributes to society by developing people who now and in the future will live with and building new homes and offices, public functions what we develop, build and construct. Peab is and infrastructure. This is how we are useful and make also a big employer with local roots and with a difference in daily life in big and small places in this comes big responsibility. Sweden, Norway and Finland. Peab is engaged in developing a more sustainable Long- term relationships with customers and suppliers society. Our goal is to meet the demands and result in better social, environmental and economic expectations from others and at the same time conditions. Stable profitability generates the funds create new business opportunities. necessary to develop our business and provide returns for our shareholders. Construction Business model Four collaborating business Most satisfied customer Project areas create added value Development Best workplace Civil Most profitable company Engineering Peab is characterized by a decentralized and cost- efficient organization with four complementary business areas whose operations are based on local entrepreneurship close to customers. Our business model with four collaborating business areas creates opportunities throughout the value chain in our projects. Industry Our three strategic goals Most satisfied customers, Best workplace and Most profitable company frame our prioritized investments in the business plan period 2018- 2020.