Spiritualism, Science, and the Supernatural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History Spiritualism

THE HISTORY of SPIRITUALISM by ARTHUR CONAN DOYLE, M.D., LL.D. former President d'Honneur de la Fédération Spirite Internationale, President of the London Spiritualist Alliance, and President of the British College of Psychic Science Volume One With Seven Plates PSYCHIC PRESS LTD First edition 1926 To SIR OLIVER LODGE, M.S. A great leader both in physical and in psychic science In token of respect This work is dedicated PREFACE This work has grown from small disconnected chapters into a narrative which covers in a way the whole history of the Spiritualistic movement. This genesis needs some little explanation. I had written certain studies with no particular ulterior object save to gain myself, and to pass on to others, a clear view of what seemed to me to be important episodes in the modern spiritual development of the human race. These included the chapters on Swedenborg, on Irving, on A. J. Davis, on the Hydesville incident, on the history of the Fox sisters, on the Eddys and on the life of D. D. Home. These were all done before it was suggested to my mind that I had already gone some distance in doing a fuller history of the Spiritualistic movement than had hitherto seen the light - a history which would have the advantage of being written from the inside and with intimate personal knowledge of those factors which are characteristic of this modern development. It is indeed curious that this movement, which many of us regard as the most important in the history of the world since the Christ episode, has never had a historian from those who were within it, and who had large personal experience of its development. -

A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion

ABSTRACT Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A., M.A. Mentor: T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D. The trouble with “definitions” is they leave no room for evolution. When a word is concretely defined, it is done so in a particular time and place. Contextual interpretations permit a better understanding of certain heavy words; Atheism as a prime example. In the post-modern world Atheism has become more accepted and popular, especially as a reaction to global terrorism. However, the current definition of Atheism is terribly inaccurate. It cannot be stated properly that pagan Atheism is the same as New Atheism. By interpreting the Atheisms from four stages in the term‟s history a clearer picture of its meaning will come out, hopefully alleviating the stereotypical biases weighed upon it. In the interpretation of the Atheisms from Pagan Antiquity, the Enlightenment, the New Atheist Movement, and the American Judicial and Civil Religious system, a defense of the theory of elastic contextual interpretations, rather than concrete definitions, shall be made. Rejecting the Definitive: A Contextual Examination of Three Historical Stages of Atheism and the Legality of an American Freedom from Religion by Ethan Gjerset Quillen, B.A., M.A. A Thesis Approved by the J.M. Dawson Institute of Church-State Studies ___________________________________ Robyn L. Driskell, Ph.D., Interim Chairperson Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Baylor University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Approved by the Thesis Committee ___________________________________ T. -

Yjyjjgl^Ji^Jihildlitr-1 What's That I Smell? the Claims of Aroma .••

NOVA EXAMINES ALIEN ABDUCTIONS • THE WEIRD WORLD WEB • DEBUNKING THE MYSTICAL IN INDIA yjyjjgl^ji^JiHildlitr-1 What's That I Smell? The Claims of Aroma .•• Fun and Fallacies with Numbers I by Marilyn vos Savant le Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL AT IHf CENIK FOR INQUKY (ADJACENT IO IME MATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director and Public Relations Director Lee Nisbet. Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock.* psychologist, York Murray Gell-Mann. professor of physics, H. Narasimhaiah, physicist, president, Univ., Toronto Santa Fe Institute; Nobel Prize laureate Bangalore Science Forum, India Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Thomas Gilovich, psychologist, Cornell Dorothy Nelkin. sociologist. New York Univ. Albany, Oregon Univ. Joe Nickell.* senior research fellow, CSICOP Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Henry Gordon, magician, columnist. Lee Nisbet.* philosopher, Medaille College Toronto Kentucky James E. Oberg, science writer Stephen Barrett. M.D., psychiatrist, Stephen Jay Gould, Museum of Loren Pankratz, psychologist, Oregon Comparative Zoology, Harvard Univ. author, consumer advocate, Allentown, Health Sciences Univ. Pa. C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist, Univ. of Wales John Paulos, mathematician, Temple Univ. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Mark Plummer, lawyer, Australia Simon Fraser Univ., Vancouver, B.C., AI Hibbs, scientist, Jet Propulsion Canada Laboratory W. V. Quine, philosopher. Harvard Univ. Irving Biederman, psychologist, Univ. of Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Milton Rosenberg, psychologist, Univ. of Chicago Southern California understanding and cognitive science, Carl Sagan, astronomer. -

Religion of Science-Fantasy Cults Martin Gardner

Summer 1987 Vol. 7, No. 3 .40,11 Was the Universe Created? Victor Stenger The New Religion of Science-Fantasy Cults Martin Gardner The Relativity of Biblical Ethics Joe Edward Barnhart Plus "Pearlygate" Morality • New Directions for Humanism • Personal Paths to Humanism with Joseph Fletcher, Anne Gaylor, Rita Mae Brown, Ashley Montagu, and Mario Bunge • Tyranny of the Creed by John Allegro _- FreeC SUMMER 1987, VOL. 7, NO. 3 ISSN 0272-0701 Contents 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 9 PERSPECTIVE 10 ON THE BARRICADES 61 IN THE NAME OF GOD 62 CLASSIFIED 6 EDITORIALS "Pearlygate" Morality Paul Kurtz / New Directions for Humanism / Catholic Consistency at Any Cost Tom Flynn 12 The Tyranny of the Creed John Allegro BELIEF AND UNBELIEF AROUND THE WORLD 14 Japan and Biblical Religion Richard L. Rubenstein 21 Letter to a Missionary Ronn Nadeau ARTICLES 22 The Relativity of Biblical Ethics Joe Edward Barnhart 25 Xenoglossy and Glossolalia Don Laycock 26 Was the Universe Created? Victor Stenger 31 Science-Fantasy Religious Cults Martin Gardner PERSONAL PATHS TO HUMANISM 36 A Secular Humanist Confession Joseph Fletcher 37 Free from Religion Anne Nicol Gay!or 38 Surrender to Life Rita Mae Brown 40 As if Living and Loving Were One Ashley Montagu 42 Growing Up Agnostic in Argentina Mario Bunge 46 The Case Against Reincarnation (Part 4) Paul Edwards BOOKS 54 The Cult of Objectivism Nathaniel Branden 55 Propaganda Before Education Gordon Stein 56 Critiquing the Old Unities Robert Basil Rita Mae Brown's and Ashler Montagu's articles are adapted by permission from The Courage of Conviction, edited by Philip Berman, published in hardcover by Dodd, Mead, and Company and in paperback by Ballantine Books. -

The Science of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival

Rollins College Rollins Scholarship Online Master of Liberal Studies Theses 2009 The cS ience of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival Benjamin R. Cox III [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls Recommended Citation Cox, Benjamin R. III, "The cS ience of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival" (2009). Master of Liberal Studies Theses. 31. http://scholarship.rollins.edu/mls/31 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by Rollins Scholarship Online. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master of Liberal Studies Theses by an authorized administrator of Rollins Scholarship Online. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Science of Mediumship and the Evidence of Survival A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Liberal Studies by Benjamin R. Cox, III April, 2009 Mentor: Dr. J. Thomas Cook Rollins College Hamilton Holt School Master of Liberal Studies Winter Park, Florida This project is dedicated to Nathan Jablonski and Richard S. Smith Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................... 1 The Science of Mediumship.................................................................... 11 The Case of Leonora E. Piper ................................................................ 33 The Case of Eusapia Palladino............................................................... 45 My Personal Experience as a Seance Medium Specializing -

Gardner on Exorcisms • Creationism and 'Rare Earth' • When Scientific Evidence Is the Enemy

GARDNER ON EXORCISMS • CREATIONISM AND 'RARE EARTH' • WHEN SCIENTIFIC EVIDENCE IS THE ENEMY THE MAGAZINE FOR SCIENCE AND REASON Volume 25, No. 6 • November/December 2001 THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION OF CLAIMS OF THE PARANORMAL AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAL (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy. State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist. York Univ., Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts Loren Pankratz, psychologist. Oregon Health Toronto and Sciences, prof, of philosophy. University Sciences Univ. Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, of Miami John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Oregon C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist. Univ. of Wales Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist. MIT Marcia Angell, M.D.. former editor-in-chief, Al Hibbs, scientist. Jet Propulsion Laboratory Massimo Polidoro, science writer, author, New England Journal of Medicine Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human under executive director CICAP, Italy Robert A. Baker, psychologist. Univ. of standing and cognitive science, Indiana Univ. Milton Rosenberg, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Chicago Stephen Barrett M.D., psychiatrist, author, Physics and professor of history of science. Wallace Sampson, M.D., clinical professor of consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. Harvard Univ. Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist. Simon Ray Hyman,* psychologist. Univ. of Oregon medicine, Stanford Univ., editor. Scientific Fraser Univ.. Vancouver, B.C., Canada Leon Jaroff, sciences editor emeritus, Time Review of Alternative Medicine Irving Biederman, psychologist Univ. -

Palmistry: Science Or Hand-Jive?

the Skeptical Inquirer PALMISTRY: SCIENCE OR HAND-JIVE? SRI GELLER TEST / LOCHNESS TREE TRUNK / A PILOT'S UFO WHY SKEPTICS ARE SKEPTICAL VOL. VII No. 2 WINTER 191 Published by the Committee lor the Scientific Investigation of :of the Paranormal Skeptical Inquirer THE SKEPTICAL. INQUIRER is the official journal of the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal. Editor Kendrick Frazier. Editorial Board George Abell. Martin Gardner. Ray Hyman. Philip J. Klass, Paul Kurtz, James Randi. Consulting Editors James E. Alcock, Isaac Asimov, William Sims Bainbridge. John Boardman, Milbourne Christopher. John R. Cole. Richard de Mille, C.E.M. Hansel, E.C. Krupp. James Oberg. Robert Sheaffer. Assistant Editor Doris Hawley Doyle. Production Editor Belsy Offermann. Business Manager Lynette Nisbet. Office Manager Mary Rose Hays Staff Idelle Abrams. Judy Hays. Alfreda Pidgeon Cartoonist Rob Pudim The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal Paul Kurtz, Chairman; philosopher. State University of New York at Buffalo. Lee Nisbet, Executive Director; philosopher, Medaille College. Fellows of the Committee: George Abed, astronomer, UCLA; James E. Alcock, psychologist, York Univ., Toronto; Isaac Asimov, chemist, author; Irving Biederman, psychologist. SUNY at Buffalo; Brand Blanshard, philosopher, Yale; Bart J. Bok, astronomer. Steward Observatory, Univ. of Arizona; Bette Chambers, A.H.A.; Milbourne Christopher, magician, author; L. Sprague de Camp, author, engineer; Bernard Dixon, European Editor, Omni; Paul Edwards, philosopher. Editor, Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Charles Fair, author, Antony Flew, philosopher, Reading Univ., O.K.: Kendrick Frazier, science writer. Editor. THE SKEPTICAL. INQUIRER; Yves Galifret, Exec. Secretary, I'Union Rationaliste; Martin Gardner, author. -

The Incredible Story of Father Ernetti's Chronovisor

Dowsing and Archaeology • The Onion Humor: 'Skeptic Pitied' Saddam's Giant Scorpions mrp ^^^ Hypnosis, Airplanes and Strongly Held Belief's PMS and Menstrual Disorder Myths A Patently False Patent Myth Wired to the Kitchen Sink 03 Mediumship Claims: Schwart z and Hyman Respond Published by the Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal THE COMMITTEE FOR THE SCIENTIFIC INVESTIGATION of Claims off the Paranormal AT THE CENTER FOR INQUIRY-INTERNATIONAL (ADJACENT TO THE STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK AT BUFFALO) • AN INTERNATIONAL ORGANIZATION Paul Kurtz, Chairman; professor emeritus of philosophy, State University of New York at Buffalo Barry Karr, Executive Director Joe Nickell, Senior Research Fellow Massimo Polidoro, Research Fellow Richard Wiseman, Research Fellow Lee Nisbet, Special Projects Director FELLOWS James E. Alcock,* psychologist, York Univ. Susan Haack, Cooper Senior Scholar in Arts and Loren Pankratz, psychologist, Oregon Health Toronto Sciences, prof, of philosophy, University of Miami Sciences Univ. Jerry Andrus, magician and inventor, Albany, C. E. M. Hansel, psychologist, Univ. of Wales John Paulos, mathematician. Temple Univ. Oregon Al Hibbs, scientist, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Steven Pinker, cognitive scientist MIT Marcia Angell. M.D., former editor-in-chief. New Douglas Hofstadter, professor of human Massimo Polidoro, science writer, author, execu England Journal of Medicine understanding and cognitive science, tive director CICAP Italy Robert A. Baker, psychologist, Univ. of Kentucky Indiana Univ. Milton Rosenberg, psychologist, Univ. of Stephen Barrett M.D., psychiatrist, author, Gerald Holton, Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics Chicago consumer advocate, Allentown, Pa. and professor of history of science. Harvard Wallace Sampson, M.D., clinical professor of Barry Beyerstein,* biopsychologist, Simon Univ. -

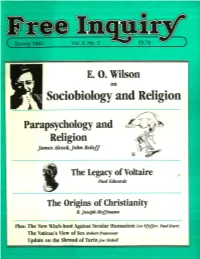

Update on the Shroud of Turin Joe Nickell SPRING 1985 ~In ISSN 0272-0701

LmAA_____., Fir ( Spring 1985 E. O. Wilson on Sociobiology and Religion Parapsychology and Religion James Alcock, John Beloff The Legacy of Voltaire Paul Edwards The Origins of Christianity R. Joseph Hoffmann Plus: The New Witch-hunt Against Secular Humanism Leo Pfeffer, Paul Kurtz The Vatican's View of Sex Robert Francoeur Update on the Shroud of Turin joe Nickell SPRING 1985 ~In ISSN 0272-0701 VOL. 5, NO. 2 Contents 3 LETTERS TO THE EDITOR 4 EDITORIALS 8 ON THE BARRICADES ARTICLES 10 Update on the Shroud of Turin Joe Nickell 11 The Vatican's View of Sex: The Inaccurate Conception Robert T. Francoeur 15 An Interview with E. O. Wilson on Sociobiology and Religion Jeffrey Saver RELIGION AND PARAPSYCHOLOGY 25 Parapsychology: The "Spiritual" Science James E. Alcock 36 Science, Religion and the Paranormal John Beloff 42 The Legacy of Voltaire (Part I) Paul Edwards 50 The Origins of Christianity: A Guide to Answering Fundamentalists R. Joseph Hoffmann BOOKS 57 Humanist Solutions Vern Bullough 58 Doomsday Environmentalism and Cancer Rodger Pirnie Doyle 59 IN THE NAME OF GOD 62 CLASSIFIED Editor: Paul Kurtz Associate Editors: Gordon Stein, Lee Nisbet, Steven L. Mitchell, Doris Doyle Managing Editor: Andrea Szalanski Contributing Editors: Lionel Abel, author, critic, SUNY at Buffalo; Paul Beattie, president, Fellowship of Religious Humanists; Jo-Ann Boydston, director, Dewey Center; Laurence Briskman, lecturer, Edinburgh University, Scotland; Vern Bullough, historian, State University of New York College at Buffalo; Albert Ellis, director, -

Magicians on the Paranormal: an Essay with a Review of Three Books

Magicians on the Paranormal: An Essay with a Review of Three Books GEORGE P. HANSEN’ ABSTRACT: Conjurors have written books on the paranormal since the 1500s. A number of these books are listed and briefly discussed herein, including those of both skeptics and proponents. Lists of magicians on both sides of the psi controversy are provided. Although many people perceive conjurors to be skeptics and debunkers, some of the most prominent magicians in history have endorsed the reality of psychic phenomena. The reader is warned that conjurors’ public statements asserting the reality of psi are sometimes difficult to eval- uate. Some mentalists publicly claim psychic abilities but privately admit that they do not believe in them; others privately acknowledge their own psychic experiences. Thme current books are fully reviewed: EntraSensory Deception by Henry Gordon (1987), Forbidden Knowledge by Bob Couttie (1988), and Secrets of the Supernatural by Joe Nickel1 (with Fischer, 1988). The books by Gordon and Couttie contain serious errors and are of little value, but the work by Nickel1 is a worthwhile contribution, though only partially concerned with psi. Magicians have been involved with paranormal controversies for cen- turies, and their participation has been far more complex and multifaceted than the usual stereotype of magicians as skeptical debunkers. In this paper, I review three fairly recent skeptical books by magicians, but before these are discussed, some remarks are in order concerning conjurors’ in- volvement with psi and psi research because there has been little useful discussion of the topic in the parapsychology literature.’ It is important to understand this background because several magicians have had an impact on scientists’ and the general public’s perception of psychical research, and some have played a major role in the modem-day skeptical movement (Hansen, 1992). -

The 'World of the Infinitely Little'

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE The 'world of the infinitely little': connecting physical and psychical realities circa 1900 AUTHORS Noakes, Richard JOURNAL Studies In History and Philosophy of Science Part A DEPOSITED IN ORE 01 December 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/41635 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication THE ‘WORLD OF THE INFINITELY LITTLE’: CONNECTING PHYSICAL AND PSYCHICAL REALITIES IN BRITAIN C. 1900 RICHARD NOAKES I: INTRODUCTION In 1918 the ageing American historian Henry Adams recalled that from the 1890s he had received a smattering of a scientific education from Samuel Pierpont Langley, the eminent astrophysicist and director of the Smithsonian Institution. Langley managed to instil in Adams his ‘scientific passion for doubt’ which undoubtedly included Langley’s sceptical view that all laws of nature were mere hypotheses and reflections of the limited and changing human perspective on the cosmos.1 Langley also pressed into the hands of his charge several works challenging the supposedly robust laws of ‘modern’ physics.2 These included the notorious critiques of mechanics, J. B. Stallo’s Concepts and Theories of Modern Physics (1881) [AND] Karl Pearson’s Grammar of Science (1892), and several recent numbers of the Smithsonian Institution’s -

Spiritualism : Is Communication with the Spirit World an Established Fact?

ti n Is Communhatm with Be an established fact? flRH ^H^^^^^H^K^^^^^^^^^^I^^B^^H^^^I^^^^^^^B^^^^HI^^^^^H bl™' ^^^^^H^^HHS^^ffiiyS^^H^^^^^^^^^I^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^BH^^BiHwv^ 1 f \ 1 PRO—WAKE COOK^H hi ''^KSBm 1 CON FRANK P0DM0rE9I i 1 l::| - ; Hodgson, AMEfilC^^ secret; ^, FLAub, B BOYLSTOtl BOSTOxM, MASS. Boston Medical Library 8 The Fenway The Pro and Con Series EDITED BY HENRY MURRAY VOL. II. /l 6 Br SPIRITUALISM " ^ SPIRITUALISM IS COMMUNICATION WITH THE SPIRIT WORLD AN ESTABLISHED FACT? PRO—E. WAKE COOK AUTHOR OF '•' THE OEGANISATION OF MAlfKIND " 'THE INCREASING PURPOSE" ETC. CON—FRANK PODMORE AUTHOR OF " MODERN SPIRITUALISM " " STUDIES IN PSYCHICAL RESEARCH" ETC. AUDI ALTERAM PARTEM LONDON ISBISTER AND COMPANY LIMITED 15 & 16 TAVISTOCK ST. COVENT GARDEN 1903 / 9. cA:/d9, Printed by Ballantyne, Hanson &> Co. London <&» Edinburgh '-OCIETY FO.- KEbt-i^i^^^- f5 BOVi-^S-V.ss. BOSTON. SPIRITUALISM—PRO BY E. WAKE COOK A Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Open Knowledge Commons and Harvard Medical School http://www.archive.org/details/spiritualismiscoOOcook SPIRITUALISM IS COMMUNICATION WITH THE SPIRIT-WORLD AN ESTABLISHED FACT? PRO PAKT I The mystery of Existence deepens. Physical Science, whose splendid advance promised to make all things clear, is taking us into mys- terious wonder-worlds, revealing profounder depths than were ever dreamt of in our philosophies, and making greater and greater demands on our powers of belief. Materialism, never either philosophically or scientifically sound, seems now to be suspended in mid-air like Mahomet's coffin. What is matter ? No one can tell us ; Sir Oliver Lodge asserting that we know more of electricity than of matter.