What Produced Four Lynchings in Duluth, Minnesota in 1918 and 1920?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Studies Journal 2013

Blending Gender: Colorado Denver University of The Flapper, Gender Roles & the 1920s “New Woman” Desperate Letters: Abortion History and Michael Beshoar, M.D. Confessors and Martyrs: Rituals in Salem’s Witch Hunt The Historic American StudiesHistorical Journal Building Survey: Historical Preservation of the Built Arts Another Face in the Crowd Commemorating Lynchings Studies Manufacturing Terror: Samuel Parris’ Exploitation of the Salem Witch Trials Journal The Whigs and the Mexican War Spring 2013 . Volume 30 Spring 2013 Spring . Volume 30 Volume Historical Studies Journal Spring 2013 . Volume 30 EDITOR: Craig Leavitt PHOTO EDITOR: Nicholas Wharton EDITORIAL STAFF: Nicholas Wharton, Graduate Student Jasmine Armstrong Graduate Student Abigail Sanocki, Graduate Student Kevin Smith, Student Thomas J. Noel, Faculty Advisor DESIGNER: Shannon Fluckey Integrated Marketing & Communications Auraria Higher Education Center Department of History University of Colorado Denver Marjorie Levine-Clark, Ph.D., Thomas J. Noel, Ph.D. Department Chair American West, Art & Architecture, Modern Britain, European Women Public History & Preservation, Colorado and Gender, Medicine and Health Carl Pletsch, Ph.D. Christopher Agee, Ph.D. Intellectual History (European and 20th Century U.S., Urban History, American), Modern Europe Social Movements, Crime and Policing Myra Rich, Ph.D. Ryan Crewe, Ph.D. U.S. Colonial, U.S. Early National, Latin America, Colonial Mexico, Women and Gender, Immigration Transpacific History Alison Shah, Ph.D. James E. Fell, Jr., Ph.D. South Asia, Islamic World, American West, Civil War, History and Heritage, Cultural Memory Environmental, Film History Richard Smith, Ph.D. Gabriel Finkelstein, Ph.D. Ancient, Medieval, Modern Europe, Germany, Early Modern Europe, Britain History of Science, Exploration Chris Sundberg, M.A. -

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey

1921 Tulsa Race Riot Reconnaissance Survey Final November 2005 National Park Service U.S. Department of the Interior CONTENTS INTRODUCTION 1 Summary Statement 1 Bac.ground and Purpose 1 HISTORIC CONTEXT 5 National Persp4l<live 5 1'k"Y v. f~u,on' World War I: 1896-1917 5 World W~r I and Postw~r ( r.: 1!1t7' EarIV 1920,; 8 Tulsa RaCR Riot 14 IIa<kground 14 TI\oe R~~ Riot 18 AIt. rmath 29 Socilot Political, lind Economic Impa<tsJRamlt;catlon, 32 INVENTORY 39 Survey Arf!a 39 Historic Greenwood Area 39 Anla Oubi" of HiOlorK G_nwood 40 The Tulsa Race Riot Maps 43 Slirvey Area Historic Resources 43 HI STORIC GREENWOOD AREA RESOURCeS 7J EVALUATION Of NATIONAL SIGNIFICANCE 91 Criteria for National Significance 91 Nalional Signifiunce EV;1lu;1tio.n 92 NMiol\ill Sionlflcao<e An.aIYS;s 92 Inl~ri ly E~alualion AnalY'is 95 {"",Iu,ion 98 Potenl l~1 M~na~menl Strategies for Resource Prote<tion 99 PREPARERS AND CONSULTANTS 103 BIBUOGRAPHY 105 APPENDIX A, Inventory of Elltant Cultural Resoun:es Associated with 1921 Tulsa Race Riot That Are Located Outside of Historic Greenwood Area 109 Maps 49 The African American S«tion. 1921 51 TI\oe Seed. of c..taotrophe 53 T.... Riot Erupt! SS ~I,.,t Blood 57 NiOhl Fiohlino 59 rM Inva.ion 01 iliad. TIll ... 61 TM fighl for Standp''''' Hill 63 W.II of fire 65 Arri~.. , of the Statl! Troop< 6 7 Fil'lal FiOlrtino ~nd M~,,;~I I.IIw 69 jii INTRODUCTION Summary Statement n~sed in its history. -

Duluth Lynchings Newspaper Index for the Duluth News Tribune

Duluth Lynchings Newspaper Index for the Duluth News Tribune June 17, 1920 through September 20, 1920 Index created by Heather Hawkins, volunteer, December 2002. Minnesota Historical Society z 345 Kellogg Blvd. West z St. Paul, Minnesota 55102-1906 1 Date Newspaper Article Name Page(s) Comments 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Duluth's Disgrace 1 editorial 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Superior Police to Deport Idle Negroes at Once 1 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune 3 Dragged from Jail and Hanged at Street Corner 1,3 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Lynchers Will Be Prosectured By Att'y Greene 1 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune 4-Hour Battle Waged By Mob to Get Victims 1,3 Long 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Attack on Girl Was Cause of Negro Lynching 3 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Negros Nabbed at Virginia Sent to Saint Paul 1 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Opposes Mob 3 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Attorney Hugh M'Clearn Attempts to Stay Mob 3 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Woman Curses Police for Failure to Save Negroes 3 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Chief Murphy Promises a Thorough Investigation 3 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Demand Quiz of Police Efforts to Defeat Mob 1,8 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Aftermath of Lynching Orgy 1 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Militiamen Kept on Duty to Help Maintain Order 1,9 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Damage to Police Headquarters by Mob Over $2,000 1 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Officials Will Act After Quiz of Mob Leaders 1,9 Long 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Guardsmen Sent to Virginia For Negro Suspects -

The Lynchings in Duluth : Second Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE LYNCHINGS IN DULUTH : SECOND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Michael Fedo | 224 pages | 15 Feb 2016 | Minnesota Historical Society Press | 9781681340135 | English | none The Lynchings in Duluth : Second Edition PDF Book There are some liberties taken with the docudrama; it's presented in a radio bulletin format, and Duluth didn't have a radio station in , Fedo noted. Melissa Taylor first saw the postcard when she was in high school. Read, 53, an associate high school principal, lived across the country in Kingston, Wash. Create An Account. As the camera flashed, some stared impassively; others grinned and slapped each other on the shoulders, stretching their necks and cocking their heads to make sure they got in the picture. Boyte incites readers to join today's "citizen movement," offering practical tools for how we can change the face of America by focusing on issues close to home. It was front-page news for the Duluth, Minn. Cloud State graduate, mixed and mastered the program, according to the university. He served about a year in state prison. Warren Read is the great-grandson of Louis Dondino, who was involved in the lynching of Black men in Boyte incites readers to join today's "citizen Together, they planted an oak tree near the grave sites of Clayton, Jackson and McGhie in Duluth in June for the anniversary of the lynchings. Miller was acquitted , but Mason was convicted and sentenced to serve seven to thirty years in prison. Christmas in Minnesota: A celebration in memories, stories,. The Lynchings in Duluth is a powerful reminder of the broader American pattern. -

Resource List

RESOURCE LIST Resources for Option A (the lynchings, Max Mason trial, and Max Mason pardon) 1. Who’s Who document 2. Video of Jerry Blackwell introducing the history of the Duluth lynchings, which includes CBS Minnesota/WCCO media clip: “Minnesota’s First Posthumous Pardon Granted to Black Man, Max Mason, Convicted in Century-Old Duluth Case” 3. Article: “On June 15, 1920, a Duluth mob lynched three black men,” by Tina Burnside | July 29, 2019 minnpost.com/mnopedia/2019/07/on-june-15-1920-a-duluth-mob-lynched-three-black- men/?gclid=CjwKCAiAl4WABhAJEiwATUnEFwBcpXPeqsMV8xeego8BBv7b33cnpJOQnLAEEc8vUr wb0IY2mv-8PhoClMUQAvD_BwE 4. Article: “Centennial remembrance of Duluth lynchings subdued - but hopeful,” by Dan Kraker | June 15, 2020 https://www.mprnews.org/story/2020/06/15/centennial-remembrance-of-duluth-lynchings- subdued-but-hopeful 5. Video: “Minnesota governor marks 100th anniversary of Duluth lynching” | Nation Jun 15, 2020 pbs.org/newshour/nation/watch-minnesota-governor-marks-100th-anniversary-of-duluth- lynching 6. History Center information regarding the lynchings, legal proceedings, and incarcerations https://www.mnhs.org/duluthlynchings/lynchings.php https://www.mnhs.org/duluthlynchings/legal.php https://www.mnhs.org/duluthlynchings/incarcerations.php 7. Max Mason pardon application, letters in support and the pardon certificate. 8. Max Mason pardon hearing 9. Article: “Minn. grants state’s first posthumous pardon to Max Mason, in case related to Duluth lynchings,” by Dan Kraker | June 12, 2020 https://www.mprnews.org/story/2020/06/12/minn-grants-states-first-posthumous-pardon-to- max-mason 10. Article: “Century after Minnesota lynchings, black man convicted of rape ‘because of his race’ up for pardon,” by Meagan Flynn | June 12, 2020 https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/06/12/duluth-lynchings-mason-pardon/ 11. -

Politics and the 1920S Writings of Dashiell Hammett 77

Politics and the 1920s Writings of Dashiell Hammett 77 Politics and the 1920s Writings of Dashiell Hammett J. A. Zumoff At first glance, Dashiell Hammett appears a common figure in American letters. He is celebrated as a left-wing writer sympathetic to the American Communist Party (CP) in the 1930s amid the Great Depression and the rise of fascism in Europe. Memories of Hammett are often associated with labor and social struggles in the U.S. and Communist “front groups” in the post-war period. During the period of Senator Joseph McCarthy’s anti-Communism, Hammett, notably, refused to collaborate with the House Un-American Activities Committee’s (HUAC) investigations and was briefly jailed and hounded by the government until his death in 1961. Histories of the “literary left” in the twentieth century, however, ignore Hammett.1 At first glance this seems strange, given both Hammett’s literary fame and his politics. More accurately, this points to the difficulty of turning Hammett into a member of the “literary left” based on his literary work, as opposed to his later political activity. At the same time, some writers have attempted to place Hammett’s writing within the context of the 1930s, some even going so far as to posit that his work had underlying left-wing politics. Michael Denning, for example, argues that Hammett’s “stories and characters . in a large part established the hard-boiled aesthetic of the Popular Front” in the 1930s.2 This perspective highlights the danger of seeing Hammett as a writer in the 1930s, instead of the 1920s. -

Cohen, Michael. “The Ku Klux Government”: Vigilantism, Lynching

JSR_v01i:JSR 12/20/06 8:14 AM Page 31 “The Ku Klux Government”: Vigilantism, Lynching, and the Repression of the IWW ■ Michael Cohen, University of California, Berkeley It is almost always the case that a “spontaneous” movement of the subaltern classes is accompanied by a reactionary movement of the right-wing of the dom- inant class, for concomitant reasons. An economic crisis, for instance, engenders on the one hand discontent among the subaltern classes and spontaneous mass movements, and on the other conspiracies among the reactionary groups, who take advantage of the objective weakening of the government in order to attempt coup d’Etat. —Antonio Gramsci 1 When the true history of this decade shall be written in other and less troubled times; when facts not hidden come to light in details now rendered vague and obscure; truth will show that on some recent date, in a secluded office on Wall Street or luxurious parlor of some wealthy club on lower Manhattan, some score of America’s kings of industry, captains of commerce and Kaisers of finance met in secret conclave and plotted the enslavement of millions of workers. Today details are obscured. The paper on which these lines are penciled is criss-crossed by the shadow of prison bars; my ears are be-set by the clang of steel doors, the jangle of fetters and the curses of jail guards. Truth, before it can speak, is stran- gled by power. Yet the big fact looms up, like a mountain above the morning mists; organ- ized wealth has conspired to enslave Labor, and—in enforcing its will—it stops at nothing, not even midnight murders and wholesale slaughter. -

America's Biggest Mass Trial, the Rise of the Justice Department, and the Fall of the IWW

H-HOAC Review: Shapiro on Strang, Keep the Wretches in Order: America's Biggest Mass Trial, the Rise of the Justice Department, and the Fall of the IWW Discussion published by John Haynes on Monday, August 9, 2021 Dean A. Strang. Keep the Wretches in Order: America's Biggest Mass Trial, the Rise of the Justice Department, and the Fall of the IWW. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2019. 344 pp. $36.95 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-299-32330-1. Reviewed by Shelby Shapiro (Independent Scholar)Published on H-Socialisms (August, 2021) Commissioned by Gary Roth (Rutgers University - Newark) Printable Version: https://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=56024 Destroying the IWW Interest in the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), or Wobblies, seems to come in waves: the 1950s saw Fred Thompson’s The I.W.W.: Its First Fifty Years (1955) while the 1960s brought Joyce Kornbluh’s Rebel Voices: An IWW Anthology (1964), Robert Tyler’s Rebels of the Woods: The I.W.W. in the Pacific Northwest (1967), Patrick Renshaw’s The Wobblies: The Story of the IWW and Syndicalism in the United States (1967), Ian Turner’s Sydneys’s Burning (1967), and Melvyn Dubofsky’s We Shall Be All (1969), to cite but a few. Entries for the twenty-first century include Lucien van der Walt’s PhD dissertation, “Anarchism and Syndicalism in South Africa, 1904-1921: Rethinking the History of Labour and the Left” (2007); Wobblies of the World: A Global History of the IWW, edited by Peter Cole, David Struthers, and Kenyon Zimmer (2017), and Peter Cole’sBen Fletcher: The Life and Times of a Black Wobbly(2021). -

Ocoee Election Day Violence – November 1920

Ocoee Election Day Violence – November 1920 Report No. 19-15 November 2019 November 2019 Report No. 19-15 Ocoee Election Day Violence – November 1920 As directed by the Legislature, OPPAGA conducted a historical review of the 1920 Election Day violence in Ocoee, Florida to provide information on the scope and effects of the incident. To complete the research for this brief, OPPAGA reviewed academic papers and books, maps, oral histories recorded by the Works Progress Administration, congressional testimony, census records, property deeds, interview notes from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) officials, death certificates from the Florida Department of Health’s Bureau of Vital Statistics, draft cards from World War I, collections at the Orange County Regional History Center, mortuary records, and hundreds of newspaper articles. In cases where there were conflicting accounts of the events, this review favors those accounts provided by eyewitnesses or people with first-hand knowledge of the event. BACKGROUND Ocoee, Florida, is a city in Orange County with a 2019 population of about 47,500 people. The city is approximately 10 miles west of Orlando and is located near the southeastern edge of Lake Apopka, between Apopka and Winter Garden and surrounding Starke Lake. (See Exhibit 1.) Exhibit 1 Map of Ocoee, Orange County, Florida Source: Google Maps. 1 The area was incorporated in the early 1920s and became the City of Ocoee in 1925. Early white settlers began to establish homesteads near Starke Lake in the 1850s, after the Seminole Indians had been resettled west of the Mississippi River or fled to South Florida. -

America Without the Death Penalty

................................ America without the Death Penalty .................................. America without the Death Penalty States Leading John F. Galliher the Way Larry W. Koch David Patrick Keys Teresa J. Guess Northeastern University Press Boston published by university press of new england hanover and london To Hugo Adam Bedau Northeastern University Press Published by University Press of New England One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766 www.upne.com ᭧ 2002 by John F. Galliher First Northeastern University Press/UPNE paperback edition 2005 Printed in the United States of America 54321 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Members of educational institutions and organizations wishing to photocopy any of the work for classroom use, or authors and publishers who would like to obtain permission for any of the material in the work, should contact Permissions, University Press of New England, One Court Street, Lebanon, NH 03766. ISBN for the paperback edition 1–55553–639–5 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data America without the death penalty : states leading the way / John F. Galliher . [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 1–55553–529–1 (cloth : alk. paper) Capital punishment—United States—States. I. Galliher, John F. HV8699.U5 G35 2002 364.66Ј0973—dc21 2002004923 -

C464c4 1920.Pdf

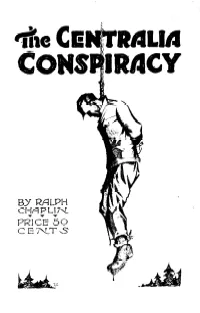

l11111111111111111111llllllllllllllllllnllnlliilllullululllullllllllulllllllllllllllllllilllilllllllllllllllllllullllllllllllllllulllulull~lllllulllllllluulll~lnlulllnlllulllllllllullilllill~lllllulllllllu~nU 6 e a aongue of JFlam q The martyr cannot be dishonored. Every lash inflicted is a tongue of flame; every prison a more illustrious abode; every burned book or house en- lightens the world; every suppres- sed or expunged word reverberates through the earth from side to side. The minds of men are at last aroused; reason looks out and justifies her own, and malice finds all her work is ruin. It is the whipper who is whipped and the tyrant who is undone.-Emerson. 8 . I1III~llUlll~ll~IIllUllllUlll~lllUUUl~llllUllllUlllllUllllllllllllllUllllllllillll~lllllllliIIUIIIIIIIIIIIIIHIIIlllllll!lllllllllllilllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllllll~ MURDER OR SELF-DEFENSE? HIS BOOKLET is not an apology for murder. It is an honest effort to unravel the tangled mesh of circumstances that led up to the Armistice Day tragedy in Centralia, Washington. The writer is one of those who believe that the tak- ing of human life is justifiable .only in self-defense. Even then the act is a horrible reversion to the brute-to the low plane of savagery. Civilization, to be worthy of the name, must afford other methods of settling human differences than those of blood letting. The nation was shocked on November 11, 1919, to read of the killing of four American Legion men by members of the In- dustrial Workers of the World in Centralia. The capitalist news- papers announced to the world that these unoffending paraders were killed in cold blood-that they were murdered from ambush without’provocation of any kind. If the author were convinced that there was even a slight possibility of this being true, he would not raise ‘his voice to defend the perpetrators of such a coward1 y crime. -

Bert Williams

he MessengerFIFTEEN CENTS A COPY . 00.000,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,00 0,000,0 A Voice From The Dead X Bert Williams An Interpretation ODHOHOHODODO - O ODCHOCHCHOCHDHOODHO THE MESSENGER [April, 1922 . Royal Theatre 15th & SOUTH STS . PHILADELPHIA WHEN IN PHILADELPHIA The Most Handsome Colored Photoplay House in Go to the America . Olympia Philadelphia Stands in a class by itself in . Prominent for the high class Photoplays shown here and the high grado music fur. Organ Theatre by our $ 30,000 Moller . nished CO-OPERATION FOR For information on organistas cooperative spelaties apply to CO -OPERATIVE LEAGUE OF AMERICA 2 Weet 13th Street New York the finest, most gripping THE MESSENGER Published Monthly by the MESSENGER PUBLISHING CO ., Inc , York . Main Office : 2305 Seventh Avenue New Telephone , Morningside 1996 Largest Motion Picture 16e. per Copy $1.50 per Year 446 TOAD ) U. S. U. S. 20. Outoldo House of its kind in $2 Outside , . No. 4. VOL . IV . APRIL 1922 South Philadelphia . CO N T E N TS I. EDITORIALS 385 388 2. EcoxOMICS AND POLITICS STS . 389 BROAD & BAINBRIDGE 3 . EDUCATION AND LITERATURE 394 4 . Who's Who 394 5. OPEN FORUM , July , , at the Entered as Second Class Mail 27 1919 , of March 3, 1879 . Post Office at New York , N.Y. under Act Editors : OWEN A. PHILIP RANDOLPH CHANDLER Contributing editor : GEORGE FRAZIER MILLER W. A. DOMINGO 385 April , 1922. ) THE MESSENGER Editorials ANTI LYNCHING LEGISLATION AND LABOR RUSSIAN CHILDREN STARVING . , Lynching labor , , THE Dyer Anti- Bill should interest WHILE the farmers in the West use corn for fuel , Out of the four thousand or more persons who millions of innocent helpless Russian children , country , be .