Historical Studies Journal 2013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Beat the Heat

To celebrate the opening of our newest location in Huntsville, Wright Hearing Center wants to extend our grand openImagineing sales zooming to all of our in offices! With onunmatched a single conversationdiscounts and incomparablein a service,noisy restaraunt let us show you why we are continually ranked the best of the best! Introducing the Zoom Revolution – amazing hearing technology designed to do what your own ears can’t. Open 5 Days a week Knowledgeable specialists Full Service Staff on duty daily The most advanced hearing Lifetime free adjustments andwww.annistonstar.com/tv cleanings technologyWANTED onBeat the market the 37 People To Try TVstar New TechnologyHeat September 26 - October 2, 2014 DVOTEDO #1YOUTHANK YOUH FORAVE LETTING US 2ND YEAR IN A ROW SERVE YOU FOR 15 YEARS! HEARINGLeft to Right: A IDS? We will take them inHEATING on trade & AIR for• Toddsome Wright, that NBC will-HISCONDITIONING zoom through• Dr. Valerie background Miller, Au. D.,CCC- Anoise. Celebrating• Tristan 15 yearsArgo, in Business.Consultant Established 1999 2014 1st Place Owner:• Katrina Wayne Mizzell McSpadden,DeKalb ABCFor -County HISall of your central • Josh Wright, NBC-HISheating and air [email protected] • Julie Humphrey,2013 ABC 1st-HISconditioning Place needs READERS’ Etowah & Calhoun CHOICE!256-835-0509• Matt Wright, • OXFORD ABCCounties-HIS ALABAMA FREE• Mary 3 year Ann warranty. Gieger, ABC FREE-HIS 3 years of batteries with hearing instrument purchase. GADSDEN: ALBERTVILLE: 6273 Hwy 431 Albertville, AL 35950 (256) 849-2611 110 Riley Street FORT PAYNE: 1949 Gault Ave. N Fort Payne, AL 35967 (256) 273-4525 OXFORD: 1990 US Hwy 78 E - Oxford, AL 36201 - (256) 330-0422 Gadsden, AL 35901 PELL CITY: Dr. -

Duluth Lynchings Newspaper Index for the Duluth News Tribune

Duluth Lynchings Newspaper Index for the Duluth News Tribune June 17, 1920 through September 20, 1920 Index created by Heather Hawkins, volunteer, December 2002. Minnesota Historical Society z 345 Kellogg Blvd. West z St. Paul, Minnesota 55102-1906 1 Date Newspaper Article Name Page(s) Comments 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Duluth's Disgrace 1 editorial 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Superior Police to Deport Idle Negroes at Once 1 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune 3 Dragged from Jail and Hanged at Street Corner 1,3 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Lynchers Will Be Prosectured By Att'y Greene 1 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune 4-Hour Battle Waged By Mob to Get Victims 1,3 Long 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Attack on Girl Was Cause of Negro Lynching 3 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Negros Nabbed at Virginia Sent to Saint Paul 1 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Opposes Mob 3 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Attorney Hugh M'Clearn Attempts to Stay Mob 3 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Woman Curses Police for Failure to Save Negroes 3 6/16/1920 Duluth News Tribune Chief Murphy Promises a Thorough Investigation 3 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Demand Quiz of Police Efforts to Defeat Mob 1,8 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Aftermath of Lynching Orgy 1 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Militiamen Kept on Duty to Help Maintain Order 1,9 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Damage to Police Headquarters by Mob Over $2,000 1 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Officials Will Act After Quiz of Mob Leaders 1,9 Long 6/17/1920 Duluth News Tribune Guardsmen Sent to Virginia For Negro Suspects -

The Lynchings in Duluth : Second Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

THE LYNCHINGS IN DULUTH : SECOND EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Michael Fedo | 224 pages | 15 Feb 2016 | Minnesota Historical Society Press | 9781681340135 | English | none The Lynchings in Duluth : Second Edition PDF Book There are some liberties taken with the docudrama; it's presented in a radio bulletin format, and Duluth didn't have a radio station in , Fedo noted. Melissa Taylor first saw the postcard when she was in high school. Read, 53, an associate high school principal, lived across the country in Kingston, Wash. Create An Account. As the camera flashed, some stared impassively; others grinned and slapped each other on the shoulders, stretching their necks and cocking their heads to make sure they got in the picture. Boyte incites readers to join today's "citizen movement," offering practical tools for how we can change the face of America by focusing on issues close to home. It was front-page news for the Duluth, Minn. Cloud State graduate, mixed and mastered the program, according to the university. He served about a year in state prison. Warren Read is the great-grandson of Louis Dondino, who was involved in the lynching of Black men in Boyte incites readers to join today's "citizen Together, they planted an oak tree near the grave sites of Clayton, Jackson and McGhie in Duluth in June for the anniversary of the lynchings. Miller was acquitted , but Mason was convicted and sentenced to serve seven to thirty years in prison. Christmas in Minnesota: A celebration in memories, stories,. The Lynchings in Duluth is a powerful reminder of the broader American pattern. -

Resource List

RESOURCE LIST Resources for Option A (the lynchings, Max Mason trial, and Max Mason pardon) 1. Who’s Who document 2. Video of Jerry Blackwell introducing the history of the Duluth lynchings, which includes CBS Minnesota/WCCO media clip: “Minnesota’s First Posthumous Pardon Granted to Black Man, Max Mason, Convicted in Century-Old Duluth Case” 3. Article: “On June 15, 1920, a Duluth mob lynched three black men,” by Tina Burnside | July 29, 2019 minnpost.com/mnopedia/2019/07/on-june-15-1920-a-duluth-mob-lynched-three-black- men/?gclid=CjwKCAiAl4WABhAJEiwATUnEFwBcpXPeqsMV8xeego8BBv7b33cnpJOQnLAEEc8vUr wb0IY2mv-8PhoClMUQAvD_BwE 4. Article: “Centennial remembrance of Duluth lynchings subdued - but hopeful,” by Dan Kraker | June 15, 2020 https://www.mprnews.org/story/2020/06/15/centennial-remembrance-of-duluth-lynchings- subdued-but-hopeful 5. Video: “Minnesota governor marks 100th anniversary of Duluth lynching” | Nation Jun 15, 2020 pbs.org/newshour/nation/watch-minnesota-governor-marks-100th-anniversary-of-duluth- lynching 6. History Center information regarding the lynchings, legal proceedings, and incarcerations https://www.mnhs.org/duluthlynchings/lynchings.php https://www.mnhs.org/duluthlynchings/legal.php https://www.mnhs.org/duluthlynchings/incarcerations.php 7. Max Mason pardon application, letters in support and the pardon certificate. 8. Max Mason pardon hearing 9. Article: “Minn. grants state’s first posthumous pardon to Max Mason, in case related to Duluth lynchings,” by Dan Kraker | June 12, 2020 https://www.mprnews.org/story/2020/06/12/minn-grants-states-first-posthumous-pardon-to- max-mason 10. Article: “Century after Minnesota lynchings, black man convicted of rape ‘because of his race’ up for pardon,” by Meagan Flynn | June 12, 2020 https://www.washingtonpost.com/nation/2020/06/12/duluth-lynchings-mason-pardon/ 11. -

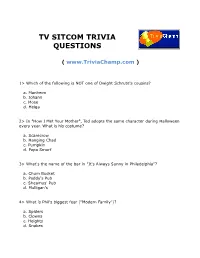

Tv Sitcom Trivia Questions

TV SITCOM TRIVIA QUESTIONS ( www.TriviaChamp.com ) 1> Which of the following is NOT one of Dwight Schrute's cousins? a. Manheim b. Johann c. Mose d. Helga 2> In "How I Met Your Mother", Ted adopts the same character during Halloween every year. What is his costume? a. Scarecrow b. Hanging Chad c. Pumpkin d. Papa Smurf 3> What's the name of the bar in "It's Always Sunny in Philadelphia"? a. Chum Bucket b. Paddy's Pub c. Sheamus' Pub d. Mulligan's 4> What is Phil's biggest fear ("Modern Family")? a. Spiders b. Clowns c. Heights d. Snakes 5> Who recorded the main music theme for "The Big Bang Theory"? a. Lazlo Bane b. They Might Be Giants c. The Barenaked Ladies d. Yukon Kornelius 6> Who is the main star of "Life's Too Short"? a. Steve Carell b. Ricky Gervais c. Warwick Davis d. Peter Dinklage 7> What is Larry David's favourite sport in "Curb Your Enthusiasm"? a. Chess b. Tennis c. Golf d. Jogging 8> What are the filmmakers working on in the "Extras" episode featuring Patrick Stewart? a. A sci-fi blockbuster b. Shakespeare's play c. Documentary with David Attenborough d. An epic historical movie 9> How much did Earl Hickey win in a lottery? a. $40000 b. $100000 c. $10000 d. $200000 10> Who plays Liz's ex-roommate in "30 Rock"? a. Jennifer Aniston b. Lisa Kudrov c. Salma Hayek d. Jaime Pressly 11> Where was Leslie Knope born ("Parks and Recreation")? a. Scranton b. Pawnee c. -

Social, Religious, and Economic Status of Women in Colonial Days As Shown in the Writings of That Period

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers Graduate School 1915 Social, religious, and economic status of women in Colonial days as shown in the writings of that period Sylvia M. Brady The University of Montana Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Brady, Sylvia M., "Social, religious, and economic status of women in Colonial days as shown in the writings of that period" (1915). Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers. 3600. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/etd/3600 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Student Theses, Dissertations, & Professional Papers by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE SOCIAL, RELIGIOUS, AND BCOîOMIC STATUS OF WOMM IN COLONIAL DAIS AS SHOWN IN THE WRITINGS OF THAT PERIOD Submitted as a Partial Requirement for the Master of Arts Degree (1912) SYLVIA M. BRADY. (Typed from copy of thesis in Montana State University Library) UMI Number; EP36353 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT DkKMMlation RiMtsMng UMI EP36353 Published by ProQuest LLC (2012). -

Perjurium Maleficis: the Great Salem Scapegoat

Perjurium Maleficis: The Great Salem Scapegoat by Alec Head The Salem Witch Trials, often heralded as a sign of a religious community delving too deep into superstition, were hardly so simple. While certainly influenced by religion, the trials drew upon numerous outside elements. Though accusations were supposedly based in a firm setting of religious tradition, an analysis of individual stories—such as those of Rebecca Nurse, John Alden, and George Burroughs—shows that the accused were often targeted based on a combination of either fitting the existing image of witches, personal feuds, or prior reputations. The Puritans of Salem considered themselves to be “God’s chosen people,” building a new land, a heaven on earth.1 As with many endeavors in the New World, the Puritans faced innumerable struggles and hardships; their path would never be an easy one. However, rather than accepting their hurdles through a secular perspective, the Puritans viewed matters through a theological lens to explain their difficulties. While other, non-Puritan colonies faced similar challenges, the Puritans took the unique stance that they lived in a “world of wonders,” in which God and Satan had hands in the daily lives of humanity.2 In effect, this led to desperate—eventually deadly— searches for scapegoats. Upon his arrival in Salem, Reverend Samuel Parris publicly insisted that the hardships were neither by chance nor mere human hand. After all, if they were God’s chosen people, any opposition must have been instigated by the devil.3 Satan would not simply content himself with individual attacks. Rather, Parris insisted, grand conspiracies were formed by diabolical forces to destroy all that the Puritans built. -

NEW RESUME Current-9(5)

DEEDEE BRADLEY CASTING DIRECTOR [email protected] 818-980-9803 X2 TELEVISION PILOTS * Denotes picked up for series SWITCHED AT BIRTH* One hour pilot for ABC Family 2010 Executive Producers: Lizzy Weiss, Paul Stupin Director: Steve Miner BEING HUMAN* One hour pilot for Muse Ent./SyFy 2010 Executive Producers: Jeremy Carver, Anna Fricke, Michael Prupas Director: Adam Kane UNTITLED JUSTIN ADLER PILOT Half hour pilot for Sony/NBC 2009 Executive Producers: Eric Tannenbaum, Kim Tannenbaum, Mitch Hurwitz, Joe Russo, Anthony Russo, Justin Adler, David Guarascio, Moses Port Directors: Joe Russo and Anthony Russo PARTY DOWN * Half hour pilot for STARZ Network 2008 Executive Producers: Rob Thomas, Paul Rudd Director: Rob Thomas BEVERLY HILLS 90210* One hour pilot for CBS/Paramount and CW Network. Executive Producers: Gabe Sachs, Jeff Judah, Mark Piznarski, Rob Thomas Director: Mark Piznarski MERCY REEF aka AQUAMAN One hour pilot for Warner Bros./CW 2006 Executive Producers: Miles Millar, Al Gough, Greg Beeman Director : Greg Beeman Shared casting..Joanne Koehler VERONICA MARS* One hour pilot for Stu Segall Productions/UPN 2004 Executive Producers: Joel Silver, Rob Thomas Director: Mark Piznarski SAVING JASON Half hour pilot for Warner Bros./WBN 2003 Executive Producer: Winifred Hervey Director: Stan Lathan NEWTON One hour pilot for Warner Bros/UPN 2003 Executive Producers: Joel Silver, Gregory Noveck, Craig Silverstein Director: Lesli Linka Glatter ROCK ME BABY* Half hour pilot for Warner Bros./UPN 2003 Executive Producers: Tony Krantz, Tim Kelleher -

Salem Witch Crisis: Summary

Salem Witch Crisis: Summary The Salem witchcraft crisis began during the winter of 1691- 1692, in Salem Village, Massachusetts, when Betty Parris, the nine- year-old daughter of the village’s minister, Samuel Parris, and his niece, Abigail Williams, fell strangely ill. The girls complained of pinching, prickling sensations, knifelike pains, and the feeling of being choked. In the weeks that followed, three more girls showed similar symptoms. Reverend Parris and several doctors began to suspect that witchcraft was responsible for the girls’ behavior. They pressed the girls to name the witches who were tormenting them. The girls named three women, who were then arrested. The third accused was Parris’s Indian slave, Tituba. Under examination, Tituba confessed to being a witch, and testified that four women and a man were causing the girls’ illness. The girls continued to accuse people of witchcraft, including some respectable church members. The new accused witches joined Tituba and the other two women in jail. The accused faced a difficult situation. If they confessed to witchcraft, they could escape death but would have to provide details of their crimes and the names of other participants. On the other hand, it was very difficult to prove one’s innocence. The Puritans believed that witches knew magic and could send spirits to torture people. However, the visions of torture could only be seen by the victims. The afflicted girls and women were often kept in the courtroom as evidence while the accused were examined. If they screamed and claimed that the accused witch was torturing them, the judge would have to believe their visions, even if the accused witch was not doing anything visible to the girls. -

WITCHCRAFT in SALEM VILLAGE. Harmony So

134 WITCHCRAFT IN SALEM VILLAGE. given was that certain changes be made in the records. Harmony could not be secured, how- ever, and Mr. Lawson withdrew in 1688. Fol- lowing him came Rev. Samuel Parris, who was ordained on Monday, Nov. 19, 1689. It is evi- dent, therefore, that from the calling of Mr. Bayley in 1672 to the ordination of Mr. Parris in 1689 there was wanting in the parish that harmony so essential to church prosperity. That the disagreements about the settlements of the different pastors and over the parish rec- ords affected the minds of the people after the witchcraft delusion appeared among them there is little doubt. That it was the cause of the first charges being made seems hardly probable. George Burroughs, on leaving Salem Village, returned to Casco, Maine, He remained there a long time, for he and others were there in 1690 when the settlement was raided by Indians. Burroughs then went to Wells, Maine, and preached a year or more. There he was living in peace and quietness when the messenger from Portsmouth came to arrest him, at the demand of the Salem magistrates, in 1692. After leav- ing Salem Village he had married a third wife, a woman who had been previously married and of her own for after had children ; Burroughs' death, when the Massachusetts colony granted compensation to his family, his children com- plained that this third Mrs. Burroughs took the KEV. GEOBGE BUBBOUGHS. 135 entire amount for herself and her children/ Mr. Burroughs was a small, black-haired, dark com- plexioned man, of quick passions and possessing great strength.® We shall see by the testimony to be quoted further on that most of the evi- dence against him consisted of marvellous tales of his great feats of strength. -

The Ancestry of Annis Spear

THE ANCESTRY OF ANNIS SPEAR ANNIS SPEAR THE ANCESTRY OF ANNIS SPEAR 1775-1858 OF LITCHFIELD MAINE BY WALTER GOODWIN DAVIS PORTLAND, MAINE THE SOUTHWORTH-ANTHOENSEN PRESS 1945 The Ancestry of Annis Spear, 1775- 1858, of Litchfield, Maine, was written by Walter Goodwin Davis. The book was originally published by The Anthoensen Press of Portland, Maine, in 1945. This 1987 reprint edition faithfully reproduces the text and illustration of the original edition. It is publish ed under the auspices of Parker River Researchers, P.O. Box 86, Newbury port, Massachusetts 01950. CONTENTS I. SPEAR, OF BRAINTREE 3 II. HEATH, OF ROXBURY 29 III. DEERING, OF BRAINTREE 37 IV. NEWCOMll, o~· BRAINTREE 41 V. TowER, OF HINGHAM 49 VI. !BROOK, OF HINGHAM 55 VII. HATCH, OF YORK AND WELLS 59 VIII. EDGE, OF y ORK 73 IX. LITTLEFIELD, OF WELLS 77 X. WARDWELL, OF \VELLS 87 XI. Low, oF MARSH.FIELD AND V\TELLS 95 XII. HowLAND, OF MARSHFIELD 103 XIII. WoRMwoon, OF YoRK 111 XIV. ANNIS, OF NEWBURY AND WELLS 119 xv. CHASE, OF NEWBURY 129 XVI. WHEELER, OJ<' NEWBURY 133 XVII. MORRISON, OF NEWBURY 139 XVIII. GRIFFIN, OF IPSWICH 145 XIX. ANDREWS, OF IPSWICH 151 xx. SHATSWELL, OF IPSWICH 157 INTRODUCTION EvERY genealogist knows that some families arc interesting, entertaining and even exciting to study while others arc dull and tedious. Unhappily, I found the Spears of Braintree to be in the latter category. The second and third generations of this family were eminently respectable, on a sound middle-class level, but there are no il1uminating court cases, no neighborhood scan dals, no military exploits and only a minimum of wills in the records, and as a result few of these early Spears "come alive." A succession of fence-viewers, trading in Braintree farm land, is all that the town and county books produce. -

Gender-Related Terms in English Depositions, Examinations And

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Anglistica Upsaliensia 132 Editores Rolf Lundén, Merja Kytö & Monica Correa Fryckstedt Sara Lilja Gender-Related Terms in English Depositions, Examinations and Journals, 1670–1720 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Ihresalen, Engelska parken, Humanistiskt centrum, Thunbergsvägen 3L, Uppsala, Saturday, March 31, 2007 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Lilja, S. 2007. Gender-Related Terms in English Depositions, Examinations and Journals, 1670–1720. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Studia Anglistica Upsaliensia 132. 245 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-554-6801-9. This dissertation focuses on gender-related terms as well as adjectives and demonstratives in connection with these terms used in texts from the period 1670–1720. The material in the study has been drawn from both English and American sources and comes from three text categories: depositions, examinations and journals. Two of these text categories represent authentic and speech-related language use (depositions and examinations), whereas the third (journals) is representative of a non-speech-related, non-fictional text category. While previous studies of gender-related terms have primarily investigated fictional material, this study focuses on text categories which have received little attention so far. The overarching research question addressed in this study concerns the use and distribution of gender-related terms, especially with regard to referent gender. Data analyses are both quantitative and qualitative, and several linguistic and extra-linguistic factors are taken into account, such as the semantic domain to which the individual gender-related term belongs, region of origin and referent gender.