The Salem Witch Trials [Type Text] Elise Forte the Many Faces of The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Studies Journal 2013

Blending Gender: Colorado Denver University of The Flapper, Gender Roles & the 1920s “New Woman” Desperate Letters: Abortion History and Michael Beshoar, M.D. Confessors and Martyrs: Rituals in Salem’s Witch Hunt The Historic American StudiesHistorical Journal Building Survey: Historical Preservation of the Built Arts Another Face in the Crowd Commemorating Lynchings Studies Manufacturing Terror: Samuel Parris’ Exploitation of the Salem Witch Trials Journal The Whigs and the Mexican War Spring 2013 . Volume 30 Spring 2013 Spring . Volume 30 Volume Historical Studies Journal Spring 2013 . Volume 30 EDITOR: Craig Leavitt PHOTO EDITOR: Nicholas Wharton EDITORIAL STAFF: Nicholas Wharton, Graduate Student Jasmine Armstrong Graduate Student Abigail Sanocki, Graduate Student Kevin Smith, Student Thomas J. Noel, Faculty Advisor DESIGNER: Shannon Fluckey Integrated Marketing & Communications Auraria Higher Education Center Department of History University of Colorado Denver Marjorie Levine-Clark, Ph.D., Thomas J. Noel, Ph.D. Department Chair American West, Art & Architecture, Modern Britain, European Women Public History & Preservation, Colorado and Gender, Medicine and Health Carl Pletsch, Ph.D. Christopher Agee, Ph.D. Intellectual History (European and 20th Century U.S., Urban History, American), Modern Europe Social Movements, Crime and Policing Myra Rich, Ph.D. Ryan Crewe, Ph.D. U.S. Colonial, U.S. Early National, Latin America, Colonial Mexico, Women and Gender, Immigration Transpacific History Alison Shah, Ph.D. James E. Fell, Jr., Ph.D. South Asia, Islamic World, American West, Civil War, History and Heritage, Cultural Memory Environmental, Film History Richard Smith, Ph.D. Gabriel Finkelstein, Ph.D. Ancient, Medieval, Modern Europe, Germany, Early Modern Europe, Britain History of Science, Exploration Chris Sundberg, M.A. -

Gender-Related Terms in English Depositions, Examinations And

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Anglistica Upsaliensia 132 Editores Rolf Lundén, Merja Kytö & Monica Correa Fryckstedt Sara Lilja Gender-Related Terms in English Depositions, Examinations and Journals, 1670–1720 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Ihresalen, Engelska parken, Humanistiskt centrum, Thunbergsvägen 3L, Uppsala, Saturday, March 31, 2007 at 10:15 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Lilja, S. 2007. Gender-Related Terms in English Depositions, Examinations and Journals, 1670–1720. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Studia Anglistica Upsaliensia 132. 245 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 978-91-554-6801-9. This dissertation focuses on gender-related terms as well as adjectives and demonstratives in connection with these terms used in texts from the period 1670–1720. The material in the study has been drawn from both English and American sources and comes from three text categories: depositions, examinations and journals. Two of these text categories represent authentic and speech-related language use (depositions and examinations), whereas the third (journals) is representative of a non-speech-related, non-fictional text category. While previous studies of gender-related terms have primarily investigated fictional material, this study focuses on text categories which have received little attention so far. The overarching research question addressed in this study concerns the use and distribution of gender-related terms, especially with regard to referent gender. Data analyses are both quantitative and qualitative, and several linguistic and extra-linguistic factors are taken into account, such as the semantic domain to which the individual gender-related term belongs, region of origin and referent gender. -

Sarah Vibber: the Accuser Who Managed to Stay on the Right Side of Wrong During

1 Annie Roman Professor Norton Hist. 2090 November 29, 2017 Sarah Vibber: The Accuser Who Managed to Stay on the Right Side of Wrong During the Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692 Introduction The Salem witchcraft crisis began in January 1692 when two young girls named Abigail Williams and Betty Parris fell ill. Betty’s father, the Reverend Samuel Parris, consulted the only doctor in Salem Village, who diagnosed the girls as being “under an Evil Hand.”1 Soon after that, Abigail and Betty accused Parris’ slave of bewitching them, thus setting off a chain of accusations and arrests that would result in the deaths of twenty innocent people. Although most of the accusers were girls and teenagers, older women also claimed to be afflicted. Four married women, including Bathshua Pope, Ann Putnam, Sr., Margaret Goodale, and Sarah Vibber, joined the girls in claiming to be tormented by the apparitions of supposed witches. At thirty-six, Sarah Vibber was the oldest afflicted person who made formal legal complaints during the witchcraft crisis, and she was a crucial witness for the court. Mary Beth Norton noted in In the Devil’s Snare that adult men played a critical role in legitimizing the complaints of the afflicted girls and women. During the Salem witchcraft crisis, accusations made by afflicted women and children only resulted in legal action if adult male “gatekeepers” found those accusations credible. According to Norton, female accusers 1 Mary Beth Norton, In the Devil’s Snare: The Salem Witchcraft Crisis of 1692, (NY: Alfred A. Knopf, 2002), 19. 2 confronted three levels of male gatekeepers (heads of households, examining magistrates, and judges and jurors) when seeking justice.2 Bathshua Pope, for example, claimed to be afflicted during examinations, but made no depositions or statements. -

The Nature of Knowledge: Evidence and Evidentiality in the Witness Depositions from the Salem Witch Trials.” American Speech 87(1): 7–38

KU ScholarWorks | http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Please share your stories about how Open Access to this article benefits you. The Nature of Knowledge: Evidence and Evidentiality in the Witness Depositions from the Salem Witch Trials by Peter Grund 2012 This is the author’s accepted manuscript, post peer-review. The original published version can be found at the link below. Grund, Peter. 2012. “The Nature of Knowledge: Evidence and Evidentiality in the Witness Depositions from the Salem Witch Trials.” American Speech 87(1): 7–38. Published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/00031283-1599941 Terms of Use: http://www2.ku.edu/~scholar/docs/license.shtml This work has been made available by the University of Kansas Libraries’ Office of Scholarly Communication and Copyright. Peter J. Grund. 2012. “The Nature of Knowledge: Evidence and Evidentiality in the Witness Depositions from the Salem Witch Trials.” American Speech 87(1): 7–38. (accepted manuscript version, post-peer review) The Nature of Knowledge: Evidence and Evidentiality in the Witness Depositions from the Salem Witch Trials PETER J. GRUND University of Kansas Abstract: This article explores evidentiality (or the linguistic marking of source of information), a topic that has received little attention in studies on the history of English. Using witness depositions from the witch trials in Salem, MA, in 1692–1693 as material, the article reveals that a number of linguistic features are used to indicate source of information, especially verb phrases (e.g. see, hear, tell) and prepositional phrases (e.g. to my knowledge, in my sight). It also shows that direct sensory experience and reports are the most common semantic categories of evidentiality in the documents, while inference and assumption are relatively uncommon. -

The Anatomy of Correction: Additions

KU ScholarWorks | http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Please share your stories about how Open Access to this article benefits you. The Anatomy of Correction: Additions, Cancellations, and Changes in the Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Trials by Peter Grund 2007 This is the author’s accepted manuscript, post peer-review. The original published version can be found at the link below. Peter Grund. 2007. “The Anatomy of Correction: Additions, Cancellations, and Changes in the Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Trials.” Studia Neophilologica 79(1): 3–24. Published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00393270701287439 Terms of Use: http://www2.ku.edu/~scholar/docs/license.shtml This work has been made available by the University of Kansas Libraries’ Office of Scholarly Communication and Copyright. Peter Grund. 2007. “The Anatomy of Correction: Additions, Cancellations, and Changes in the Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Trials.” Studia Neophilologica 79(1): 3–24. (accepted manuscript version, post-peer review) The Anatomy of Correction: Additions, Cancellations, and Changes in the Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Trials1 Peter Grund, Uppsala University 1. Introduction The Salem witchcraft trials of 1692 hold a special place in early American history. Though limited in comparison with many European witch persecutions, the Salem trials have reached mythical proportions, particularly in the United States. The some 1,000 extant documents from the trials and, in particular, the pre-trial hearings have been analyzed from various perspectives by (social) historians, anthropologists, biologists, medical doctors, literary scholars, and linguists (see e.g. Rosenthal 1993: 33–36; Mappen 1996; Grund, Kytö and Rissanen 2004: 146). But despite this intense interest in the trials, very little research has been carried out on the actual manuscript documents that have survived from the trials. -

8.5 X12.5 Doublelines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-66166-9 - Records of the Salem Witch-Hunt Edited by Bernard Rosenthal Frontmatter More information RECORDS OF THE SALEM WITCH-HUNT This book represents the first comprehensive record of all legal documents per- taining to the Salem witch trials, in chronological order. Numerous newly dis- covered manuscripts, as well as records published in earlier books that were over- looked in other editions, offer a narrative account of the much-written-about episode in 1692–93. The book may be used as a reference book or read as an unfolding narrative. All legal records are newly transcribed, and errors in previous editions have been corrected. Included in this edition is a historical introduction, a legal introduction, and a linguistic introduction. Manuscripts are accompanied by notes that, in many cases, identify the person who wrote the record. This has never been attempted, and much is revealed by seeing who wrote what, when. Bernard Rosenthal has written widely on American literature and culture. His monographs include City of Nature and Salem Story, and he has also edited many published volumes, including The Oregon Trail by Francis Parkman, Jr. He is also the author of numerous articles and reviews. Rosenthal has received at different times four grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities as well as a grant from the National Historical Publications and Records Commission in support of this book. One of his NEH grants was in collaboration with Benjamin Ray, partially in support of this book; another was to support this book’s comple- tion. -

Syllabus for My Salem Witch Trials Graduate Course

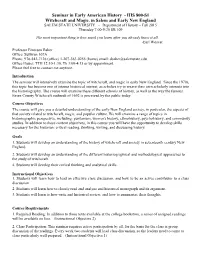

Seminar in Early American History - HIS 800-S1 Witchcraft and Magic, in Salem and Early New England SALEM STATE UNIVERSITY - Department of History – Fall 2015 Thursday 7:00-9:20 SB 109 The most important thing is how much you learn after you already know it all. -Earl Weaver Professor Emerson Baker Office: Sullivan 107A Phone: 978-542-7126 (office) 1-207-363-0255 (home) email: [email protected] Office Hours: TTH 12:10-1:30, Th 3:00-4:15 or by appointment. Please feel free to contact me anytime. Introduction The seminar will intensively examine the topic of witchcraft, and magic in early New England. Since the 1970s, this topic has become one of intense historical interest, as scholars try to weave their own scholarly interests into the historiography. The course will examine these different schools of history, as well as the way the famous Essex County Witchcraft outbreak of 1692 is perceived by the public today. Course Objectives The course will give you a detailed understanding of the early New England society, in particular, the aspects of that society related to witchcraft, magic, and popular culture. We will examine a range of topics in historiographic perspective, including: puritanism, women's history, ethnohistory, psychohistory, and community studies. In addition to these content objectives, in this course you will have the opportunity to develop skills necessary for the historian: critical reading, thinking, writing, and discussing history. Goals 1. Students will develop an understanding of the history of witchcraft and society in seventeenth century New England. 2. Students will develop an understanding of the different historiographical and methodological approaches to the study of witchcraft. -

Male Witches in Colonial New England

Western Washington University Western CEDAR WWU Graduate School Collection WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship 2011 Unruly men, improper patriarchs: male witches in colonial New England Rachel E. (Rachel Elizabeth) Lilley Western Washington University Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet Part of the Archival Science Commons Recommended Citation Lilley, Rachel E. (Rachel Elizabeth), "Unruly men, improper patriarchs: male witches in colonial New England" (2011). WWU Graduate School Collection. 163. https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwuet/163 This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Graduate School Collection by an authorized administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Unruly Men, Improper Patriarchs: Male Witches in Colonial New England By Rachel Elizabeth Lilley Accepted in Partial Completion Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts Moheb A. Ghali, Dean of the Graduate School ADVISORY COMMITTEE Chair, Dr. Susan Amanda Eurich Dr. Laurie Hochstetler Dr. Kathleen Kennedy MASTER’S THESIS In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master‟s degree at Western Washington University, I grant to Western Washington University the non- exclusive royalty-free right to archive, reproduce, distribute, and display the thesis in any and all forms, including electronic format, via any digital library mechanisms maintained by WWU. I represent and warrant this is my original work, and does not infringe or violate any rights of others. I warrant that I have obtained written permissions from the owner of any third party copyrighted material in these files. -

Apple Harvest Day Kicks Off Saturday

In This Issue: Friday, October 6, 2017 Apple Harvest Day kicks off Saturday Apple Harvest Day parking and traffic restrictions Clerk's office unable to process motor vehicle registrations during state computer upgrade City offices closed on Columbus Day City Council to hold Keno games public hearing Oct. 11 Catch up with the mayor and superintendent over coffee Filing period for municipal election opens Sept. 11 Chamber, Dover Listens to host "Conversation with the Candidates" Apple Harvest Day Sunday hours at the Recycling Center begin Oct. 22 kicks off Saturday Check it Out! at the Dover Library The 33rd annual Apple Harvest Day kicks off Saturday, from 9 a.m. to 4 p.m. Apple Harvest Day is filled with Article Title food, fun, and festivities. The annual event draws more City of Dover employment than 50,000 people to downtown Dover. opportunities Stay informed with City of Apple Harvest Day this year features children's activities, Dover special announcements a 5k Road Race, Apple Pie Contest, entertainment on City boards and commissions multiple stages, pancake breakfast, food, handcrafted seek to fill several vacancies arts, and much more. Discover Dover with Peek at the Week Apple Harvest Day festivities will take place in several locations in the central downtown area. Much of the activities will be located near the intersection of Washington Street and Central Street. A number of Meetings this week: designated parking areas will be available for visitors. City Council, Oct. 11, 7 For more information, a complete schedule of events, to p.m. register for the 5k or apple pie contest, or a Apple Harvest Day map, visit https://www.dovernh.org/apple- The City Council will hold a harvest-day. -

Santoro 1 Emily Santoro History 2090 Professor Norton 6 December 2010

Santoro 1 Emily Santoro History 2090 Professor Norton 6 December 2010 Samuel Parris as a Recorder The Salem witchcraft crisis of 1692 developed from a fairly common circumstance into a unique and complicated event. Fortunately court records, town records, and letters from the time period survived to assist contemporary scholars to understand and explain its occurrence. Recently, handwriting analysis on these documents identified some recorders and enabled a closer analysis of these papers. This knowledge can answer the questions of why a recorder wrote specific documents and what his judicial role was on a certain day. The Salem Village minister, Samuel Parris, actively participated in the Salem witch trials. His daughter, Elizabeth Parris, and his niece Abigail Williams, were two of the first afflicted girls and accusers during the crisis. Further, Parris recorded several judicial documents in 1692 and an obvious pattern emerged. Samuel Parris’s role as a recorder in the Salem witchcraft trials depended on the involvement of his niece, Abigail Williams, and his church members. In addition, the accused mentioned in the documents written by Parris and their families tended not to sign the petition supporting him in 1695 which suggests continued animosity. Out of the 980 documents concerning the Salem witch trials, Samuel Parris’s handwriting has been identified on 48.1 Why had Parris written these particular documents? Since he did not record a majority of them, he did not have an official role recording all of the trials and associated papers. On the other hand, the figure indicates his recording was not done on rare occasions. -

Additions, Cancellations, and Changes in the Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Trials.” Studia Neophilologica 79(1): 3–24

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by KU ScholarWorks KU ScholarWorks | http://kuscholarworks.ku.edu Please share your stories about how Open Access to this article benefits you. The Anatomy of Correction: Additions, Cancellations, and Changes in the Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Trials by Peter Grund 2007 This is the author’s accepted manuscript, post peer-review. The original published version can be found at the link below. Peter Grund. 2007. “The Anatomy of Correction: Additions, Cancellations, and Changes in the Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Trials.” Studia Neophilologica 79(1): 3–24. Published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00393270701287439 Terms of Use: http://www2.ku.edu/~scholar/docs/license.shtml This work has been made available by the University of Kansas Libraries’ Office of Scholarly Communication and Copyright. Peter Grund. 2007. “The Anatomy of Correction: Additions, Cancellations, and Changes in the Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Trials.” Studia Neophilologica 79(1): 3–24. (accepted manuscript version, post-peer review) The Anatomy of Correction: Additions, Cancellations, and Changes in the Documents of the Salem Witchcraft Trials1 Peter Grund, Uppsala University 1. Introduction The Salem witchcraft trials of 1692 hold a special place in early American history. Though limited in comparison with many European witch persecutions, the Salem trials have reached mythical proportions, particularly in the United States. The some 1,000 extant documents from the trials and, in particular, the pre-trial hearings have been analyzed from various perspectives by (social) historians, anthropologists, biologists, medical doctors, literary scholars, and linguists (see e.g.