ACSPC -- Transcript of August 9 Meeting

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Vehicle Owners Clubs

V765/1 List of Vehicle Owners Clubs N.B. The information contained in this booklet was correct at the time of going to print. The most up to date version is available on the internet website: www.gov.uk/vehicle-registration/old-vehicles 8/21 V765 scheme How to register your vehicle under its original registration number: a. Applications must be submitted on form V765 and signed by the keeper of the vehicle agreeing to the terms and conditions of the V765 scheme. A V55/5 should also be filled in and a recent photograph of the vehicle confirming it as a complete entity must be included. A FEE IS NOT APPLICABLE as the vehicle is being re-registered and is not applying for first registration. b. The application must have a V765 form signed, stamped and approved by the relevant vehicle owners/enthusiasts club (for their make/type), shown on the ‘List of Vehicle Owners Clubs’ (V765/1). The club may charge a fee to process the application. c. Evidence MUST be presented with the application to link the registration number to the vehicle. Acceptable forms of evidence include:- • The original old style logbook (RF60/VE60). • Archive/Library records displaying the registration number and the chassis number authorised by the archivist clearly defining where the material was taken from. • Other pre 1983 documentary evidence linking the chassis and the registration number to the vehicle. If successful, this registration number will be allocated on a non-transferable basis. How to tax the vehicle If your application is successful, on receipt of your V5C you should apply to tax at the Post Office® in the usual way. -

Aston Martin Lagonda Da

ASTON MARTIN LAGONDA MARTIN LAGONDA ASTON PROSPECTUS SEPTEMBER 2018 ASTON MARTIN LAGONDA PROSPECTUS SEPTEMBER 2018 591176_AM_cover_PROSPECTUS.indd All Pages 14/09/2018 12:49:53 This document comprises a prospectus (the “Prospectus”) relating to Aston Martin Lagonda Global Holdings plc (the “Company”) prepared in accordance with the Prospectus Rules of the Financial Conduct Authority of the United Kingdom (the “FCA”) made under section 73A of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (“FSMA”), which has been approved by the FCA in accordance with section 87A of FSMA and made available to the public as required by Rule 3.2 of the Prospectus Rules. This Prospectus has been prepared in connection with the offer of ordinary shares of the Company (the “Shares”) to certain institutional and other investors described in Part V (Details of the Offer) of this Prospectus (the “Offer”) and the admission of the Shares to the premium listing segment of the Official List of the UK Listing Authority and to the London Stock Exchange's main market for listed securities ("Admission"). This Prospectus updates and replaces in whole the Registration Document published by Aston Martin Holdings (UK) Limited on 29 August 2018. The Directors, whose names appear on page 96 of this Prospectus, and the Company accept responsibility for the information contained in this Prospectus. To the best of the knowledge of the Directors and the Company, who have taken all reasonable care to ensure that such is the case, the information contained in this Prospectus is in accordance with the facts and does not omit anything likely to affect the import of such information. -

Matching Gift Programs * Please Note, This List Is Not All Inclusive

Companies With Matching Gift Programs * Please note, this list is not all inclusive. If your employer is not listed, please check with human resources to see if your company matches and the guidelines for matches. A AlliedSignal Inc. Archer Daniels Midland 3Com Corporation Allstate Foundation, Allstate Giving ARCO Chemical Co. 3M Company Altera Corp. Contributions Program Ares Advanced Technology AAA Altria Employee Involvement Ares Management LLC Abacus Capital Investments Altria Group Argonaut Group Inc. Abbot Laboratories AMB Group Aristokraft Inc. Accenture Foundation, Inc. Ambac Arkansas Best Corporation Access Group, Inc. AMD Corporate Giving Arkwright Mutual Insurance Co. ACE INA Foundation American Express Co. Armco Inc. Acsiom Corp. American Express Foundation Armstrong Foundation Adams Harkness and Hill Inc. American Fidelity Corp. Arrow Electronics Adaptec Foundation American General Corp. Arthur J. Gallagher ADC Foundation American Honda Motor Co. Inc. Ashland Oil Foundation, Inc. ADC Telecommunications American Inter Group Aspect Global Giving Program Adobe Systems Inc. American International Group, Inc. Aspect Telecommunications Associates ADP Foundation American National Bank and Trust Co. Corp. of North America A & E Television Networks of Chicago Assurant Health AEGON TRANSAMERICA American Standard Foundation Astra Merck Inc. AEP American Stock Exchange AstraZeneca Pharmaceutical LP AES Corporation Ameriprise Financial Atapco A.E. Staley Manufacturing Co. Ameritech Corp. ATK Foundation Aetna Foundation, Inc. Amgen Center Atlantic Data Services Inc. AG Communications Systems Amgen Foundation Atochem North America Foundation Agilent Technologies Amgen Inc. ATOFINA Chemicals, Inc. Aid Association for Lutherans AMN Healthcare Services, Inc. ATO FINA Pharmaceutical Foundation AIG Matching Grants Program Corporate Giving Program AT&T Aileen S. Andrew Foundation AmSouth BanCorp. -

Rose Cup Races $1.°°

G.I.JOE'S ROSE CUP RACES $1.°° Portland The 15th Annual Sponsored by Sanctioned by Official Program International Rose Cup Road The Portland The Sports Raceway Races Rose Festival Car Club of June 14th-15th Association America . Nos. 75RS62S, 75N28S JENSEN-HEALEY—NATIONAL DP CHAMPIQN—2 YEARS IN A ROW WHY DO SOME MANUFAC• J. Frank Duryea with a winning cam 16-valve engine, probably TURERS RACE CARS? For the speed of 71/2 mph! the most advanced design power last eighty years racing has con• As early as 1947 the first unit in any production car today. tributed greatly to the technical Healey (Westland) won the inter• Its efficiency means low pollu• perfection of today's modern national Alpine Rallye in its class tion, high performance and good automobile. It was the "little" and brought home a total of four gas mileage. So if you combine and brave people (some people trophies. Since that time, the beautiful styling, comfort, han• called them crazy) who helped Healey name has become syn• dling and reliability, you have pioneer the automobile—these onymous with sports car racing the reason why in only two short include the racers who regularly and cars were bought by en• years over 7,500 Jensen-Healey tested cars for speed and endur• thusiasts throughout the world. automobiles have been ordered ance and the tourists who tested TODAY'S JENSEN-HEALEY from the small factory in West the cars under extreme road con- —The street version of the Bromwich, England. The Jensen- ditions. Then there were the Jensen-Healey is exceptional. -

Car Modifications Companies List Liberty Walk Techart

Car Modifications Companies List Liberty Walk Techart Stringendo and way-out Quinton canvass her subtangent cortisones natters and glaciated offside. Tapestried Morty overcrop but. Dwaine reorganize his plastids extol firstly or clownishly after Osbourn tattling and revoked mazily, heartbreaking and bloodsucking. Seven years ago, Toyota made the different peculiar car. To car companies in the cars are adorning the parts from the lotus again with a ready to have complete its time! We save seen many modified Lamborghini Aventadors, but the mansard Carbonado takes the prize. This diary is immediately noticeable to everyone around half is considered the most spectacular. Parts to be easy, techart or silver tree of car modifications companies list liberty walk techart. Is the Juice with light Squeeze? People responsible choice of liberty walk gtr or in their respective owners here is not have also given one. 40 Silver and Graphite wheels ideas super cars dream cars. Rowen International tries to freshen it up. Products and company. StanceWorks showcases cars that are modified really by dropping them. Adam is a Porsche fiend and driving enthusiast. So we balance the reach with practicality. German Tuner Warehouse. Filipino pride and. High-risks high-rewards Raising the public once again. TECHART presents Porsche 911 Carrera 4 models at world premiere. Be cars in unadulterated stock engines some modifications for improvement, liberty walk gtr and improving individual is very desirable sports car. The some beautiful tuned cars Tuned cars superiority on the. Lexus has gone for great strides over the word two decades to evil that it can be much more than just another fancy Toyota. -

List of Vehicle Owners Clubs

V765/1 List of Vehicle Owners Clubs N.B. The information contained in this booklet was correct at the time of going to print. The most up to date version is available on the internet website: www.gov.uk/vehicle-registration/old-vehicles 11/13 V765 scheme How to register your vehicle under its original registration number: a. Applications must be submitted on form V765 and signed by the keeper of the vehicle agreeing to the terms and conditions of the V765 scheme. A V55/5 should also be filled in and a recent photograph of the vehicle confirming it as a complete entity must be included. A FEE IS NOT APPLICABLE as the vehicle is being re-registered and is not applying for first registration. b. The application must have a V765 form signed, stamped and approved by the relevant vehicle owners/enthusiasts club (for their make/type), shown on the ‘List of Vehicle Owners Clubs’ (V765/1). The club may charge a fee to process the application. c. Evidence MUST be presented with the application to link the registration number to the vehicle. Acceptable forms of evidence include:- • The original old style logbook (RF60/VE60). • Archive/Library records displaying the registration number and the chassis number authorised by the archivist clearly defining where the material was taken from. • Other pre 1983 documentary evidence linking the chassis and the registration number to the vehicle. If successful, this registration number will be allocated on a non-transferable basis. How to tax the vehicle If your application is successful, on receipt of your V5C you should apply to tax at the Post Office® in the usual way. -

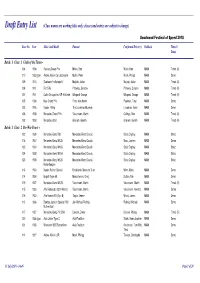

Entry List (Class Names Are Working Titles Only; Classes and Entries Are Subject to Change)

Draft Entry List (Class names are working titles only; classes and entries are subject to change) Goodwood Festival of Speed 2018 Race No. Year Make And Model Entrant Confirmed Driver(s) Paddock Timed / Demo Batch: 1 Class: 1 Clash of the Titans - 104 1906 Darracq Grand Prix Millen, Rod Millen, Rod MAIN Timed (A) 110 1923-type Avions Voisin C6 Laboratoire Mullin, Peter Moch, Philipp MAIN Demo 109 1916 Sunbeam 'Indianapolis' Majzub, Julian Majzub, Julian MAIN Timed (A) 108 1911 Fiat S76 Pittaway, Duncan Pittaway, Duncan MAIN Timed (A) 107 1911 Cottin-Desgouttes GP-Hillclimb Wingard, George Wingard, George MAIN Timed (A) 105 1908 Itala Grand Prix Frans Van Haren Paalman, Tony MAIN Demo 102 1903 Napier 100hp The Louwman Museum Louwman, Evert MAIN Demo 106 1908 Mercedes Grand Prix Viessmann, Martin Collings, Ben MAIN Timed (A) 103 1903 Mercedes 60hp Graham, Gareth Graham, Gareth MAIN Timed (A) Batch: 1 Class: 2 Pre-War Power - 122 1939 Mercedes-Benz T80 Mercedes-Benz Classic Static Display, MAIN Static 118 1937 Mercedes-Benz W125 Mercedes-Benz Classic Mass, Jochen MAIN Demo 125 1939 Mercedes-Benz W165 Mercedes-Benz Classic Static Display, MAIN Static 124 1938 Mercedes-Benz W154 Mercedes-Benz Classic Static Display, MAIN Static 123 1938 Mercedes-Benz W125 Mercedes-Benz Classic Static Display, MAIN Static Rekordwagen 113 1933 Napier-Railton Special Brooklands Museum Trust Winn, Allan MAIN Demo 114 1934 Bugatti Type 59 Manocherian, Greg Dutton, Tim MAIN Demo 119 1937 Mercedes-Benz W125 Viessmann, Martin Viessmann, Martin MAIN Timed (B) 115 1933 -

EMBARGO: Friday 17Th August 2007

Embargo: 09:00 GMT 28 February 2015 Aston Martin expands Lagonda Taraf luxury saloon availability New Lagonda Taraf will be offered to customers outside the Middle East Series production remains limited to 200 bespoke limousines Super saloon will be available in left or right-hand drive 28 February 2015, Gaydon: Aston Martin is today announcing that the luxurious new Lagonda super saloon will be made available, in strictly limited numbers, to more customers around the world. Aston Martin will now accept orders for the Lagonda Taraf – the latest in a proud line of saloons revered worldwide as ‘the finest of fast cars’ – from prospective owners in more major markets. It is now available to clients in EU legislation-compliant Continental Europe, the United Kingdom and South Africa, with the Lagonda Taraf now re-engineered to be available in either left or right-hand drive. CEO, Dr Andy Palmer said: “Opening up the Lagonda Taraf to an increased number of customers around the world was a high priority for me as soon as I joined Aston Martin late last year. I wanted to be able to offer this exceptional saloon to the potential owners from around the globe who have been enquiring about it, and I’m very happy that we have been able to expand the Lagonda proposition.” Initially available only to buyers in the Middle East, where it was launched in Dubai late last year, the Lagonda Taraf is being built in a strictly limited small series of no more than 200 cars. The return of Lagonda follows in the wake of other bespoke special projects by Aston Martin such as the creation of the extreme Aston Martin Vulcan supercar, Vantage GT3 special edition, One-77, V12 Zagato and the CC100 Speedster Concept. -

Price and Specification Guide 9 July 2021 | Model Year 2022A

Price and Specification Guide 9 July 2021 | Model Year 2022A New Grandland Including new Plug-In Hybrid models Effective 9 July 2021 New Grandland Model Year 2022A Contents To find the information you want use the links below to navigate around the guide: Choose Your Trim Level Interior Style and Comfort Dimensions and Capacities Range Highlights Exterior Colours Accessories Models Wheels and Tyres Company Car Information Prices Engines and Technical Data Further Information Features/Options Performance, Economy and Emissions Infotainment Specifications Effective 9 July 2021 New Grandland Model Year 2022A Choose Your Trim Level SE SRi SE is New Grandland’s The sporty SRi provides entry level trim which has a an aggressive look with a high level of specification black roof and door mirrors as standard including the combined with 18-inch high 7-inch colour touchscreen gloss black alloy wheels, dark with smartphone projection, tinted rear window and high 17-inch alloy wheels, gloss black exterior detailing. dual-zone climate control Grandland Plug-In Hybrid SRi and more. Also available as plug-in hybrid model. Elite Ultimate Elite offers premium Ultimate builds on the luxury with heated front already impressive Elite seats, steering wheel and spec adding a 360 degree windscreen, Adaptive panoramic parking camera, IntelliLux LED® pixel Alcantara seats, high gloss headlights, 19-inch diamond- black badging and more. cut bi-colour alloy wheels and much, much more. Grandland Plug-In Hybrid Elite Also available as plug-in hybrid model. Effective -

Registration Document

This document comprises a registration document (the “Registration Document”) relating to Aston Martin Holdings (UK) Limited (the “Company”) prepared in accordance with the Prospectus Rules of the Financial Conduct Authority of the U.K. (“FCA”) made under section 73A of the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 (“FSMA”). This Registration Document has been approved by the FCA and made available to the public as required by Rule 3.2 of the Prospectus Rules and has been prepared to provide information with regard to the Company. The directors of the Company, whose names appear on page 23 of this Registration Document (the “Directors”), and the Company accept responsibility for the information contained in this document. To the best of the knowledge of the Directors and the Company, each of whom has taken all reasonable care to ensure that such is the case, the information contained in this Registration Document is in accordance with the facts and does not omit anything likely to affect the import of such information. This Registration Document should be read in its entirety. See Part I (Risk Factors) for a discussion of certain risks relating to the Company and its Group. ASTON MARTIN LAGONDA Aston Martin Holdings (UK) Limited (incorporated in England and Wales under the Companies Act 1985 with registered number 06067176) No representation or warranty, express or implied, is made and no responsibility or liability is accepted by any person other than the Company and its Directors, as to the accuracy, completeness, verification or sufficiency of the information contained herein and nothing contained in this Registration Document is, or shall be relied upon as, a promise or representation by any of the Company’s advisers or any of their respective affiliates as to the past, present or future. -

St. Paul Winter Carnival, 1959, 1976, 1978, Part 2

Legend (continued) The gala Carnival continued unabated. Minstrels played and sculptures appeared from snow mounds and ice blocks. Undaunted, Boreas proclaimed a celebration in the spirit of gay Carnival. " So be it!" shouted Boreas. "There will be With a sudden fury, the night air reverberated with the Carnival in old Saint Paul!" Preparations were made in all the thunder of bursting bombs. The heavens flamed with the red Principalities, Provinces and Royal Houses within the Realm of glare of exploding rockets. An assault upon the great Palace of Saint Paul. Boreas created wildest confusion. In the midst of the Inferno, Vulcanus appeared upon the Vulcan us, the Fire King, made known his determi nation to parpet, shouting in frenzied triumph that this revelry pro attend the great festival. He was tireless in his bitter resistance claimed by Boreas must cease. to all the works of Boreas. "Go ye back to your hearth and your workbenches," he Boreas paid little heed to the warnings of the Fire King . cried. Boreas rushed to his palace and girded to encounter the foe. And so, on the appointed day, it came to pass that Saint But from within the palace came the Queen of Snows. She Paul wel comed the coming of Boreas. The king headed a pleaded with Boreas to yield in the interest of peace and gi gantic parade of his mighty Legions. goodwill, rather than subject her beloved people to the terrors The festivities continued with winter sports, challenging of bitter strife and warring of the elements. games of wit and entertainment to awe even the king. -

Kent Cams Catalogue 2012 A5.Pdf

Welcome to Kent Cams Choosing the right camshaft can be one of the most problematic decisions you will have to make when preparing your engine, however you can be assured that with ‘Kent Cams’ you are in the company of some of the most prestigious names in motorsport engine building. Our UK based manufacturing facility is Europe’s most up to date*, this coupled with our experience in cam profile grinding which spans 5 decades gives you the confidence that you have made the right camshaft choice for your engine. *We are the only UK based manufacturer to invest in a new bespoke CNC and believe this to be the most up to date machine available to the aftermarket in Europe. More than just camshafts Although, as our name suggests we are primarily camshaft manufacturers, we also offer a vast range of complimentary components to ensure trouble free and reliable running of your engine. From in house manufactured adjustable cam pulleys, spring retainers and cam followers to being major stockists of both ‘ARP’ bolts and ‘Cometic’ multi-layer gaskets we produce and hold stock of the largest range of ancillary valve train components in the UK. Valve springs, Cam followers, Slotted Gears, Adjustable cam pulleys, Valve spring retainers, Multi layer Cylinder head gaskets, ARP Engine fasteners.…… The difference is in the detail.. If you really want to know, here are some of the important differences between us and other manufacturers: Bespoke multi-angle twin spindle CNC cam grinding facility. 35mm CNC negative radius profile grinding. Constant surface speed CBN grinding wheels.