Written Moroccan Arabic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Etnolingwistyka Problemy Jêzyka I Kultury

ETNOLINGWISTYKA PROBLEMY JÊZYKA I KULTURY ETHNOLINGUISTICS ISSUES IN LANGUAGE AND CULTURE 28 MARIA CURIE-SK£ODOWSKA UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF HUMANITIES ETHNOLINGUISTIC COMMISSION INTERNATIONAL SLAVIC COMMITTEE ETHNOLINGUISTIC SECTION OF THE COMMITTEE OF LINGUISTICS, POLISH ACADEMY OF SCIENCES Editor−in−Chief JERZY BARTMIÑSKI Assistant to Editor STANIS£AWA NIEBRZEGOWSKA-BARTMIÑSKA Secretary MARTA NOWOSAD-BAKALARCZYK Translators ADAM G£AZ (project coordinator), RAFA£ AUGUSTYN, KLAUDIA DOLECKA, AGNIESZKA GICALA, AGNIESZKA MIERZWIÑSKA-HAJNOS Scientific Council DEJAN AJDAÈIÆ (Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, Ukraine) ELENA BEREZOVIÈ (Ural Federal University, Yekaterinburg, Russia) WOJCIECH CHLEBDA (University of Opole, Poland) ALOYZAS GUDAVIÈIUS (Šiauliai University, Lithuania) ALEKSEJ JUDIN (Ghent University, Belgium) JACEK MICHAEL MIKOŒ (University of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, USA) HANNA POPOWSKA-TABORSKA (Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland) ZUZANA PROFANTOVÁ (Slovak Academy of Sciences, Bratislava, Slovakia) SVETLANA TOLSTAJA (Russian Academy of Sciences, Moscow, Russia) ANNA WIERZBICKA (Australian National University, Canberra, Australia) KRZYSZTOF WROC£AWSKI (Polish Academy of Sciences, Warsaw, Poland) ETNOLINGWISTYKA PROBLEMY JÊZYKA I KULTURY ETHNOLINGUISTICS ISSUES IN LANGUAGE AND CULTURE 28 Lublin 2017 Maria Curie-Sk³odowska University Press Reviewers MACIEJ ABRAMOWICZ (University of Warsaw), DEJAN AJDAÈIÆ (Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv), NIKOLAJ ANTROPOV (National Academy of Sciences of Belarus), ENRIQUE -

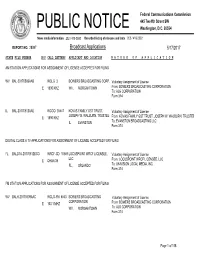

Broadcast Applications 5/17/2017

Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. 28987 Broadcast Applications 5/17/2017 STATE FILE NUMBER E/P CALL LETTERS APPLICANT AND LOCATION N A T U R E O F A P P L I C A T I O N AM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING WV BAL-20170509AAB WCLG 3 BOWERS BROADCASTING CORP. Voluntary Assignment of License E 1300 KHZ WV , MORGANTOWN From: BOWERS BROADCASTING CORPORATION To: AJG CORPORATION Form 314 IL BAL-20170512AAE WCGO 35447 KOVAS FAMILY GST TRUST, Voluntary Assignment of License JOSEPH W. WALBURN, TRUSTEE E 1590 KHZ From: KOVAS FAMILY GST TRUST, JOSEPH W. WALBURN, TRUSTEE IL , EVANSTON To: EVANSTON BROADCASTING LLC Form 314 DIGITAL CLASS A TV APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING FL BALDTA-20170512BCO WRCF-CD 10549 LOCUSPOINT WRCF LICENSEE, Voluntary Assignment of License LLC E CHAN-35 From: LOCUSPOINT WRCF LICENSEE, LLC FL , ORLANDO To: UNIVISION LOCAL MEDIA, INC. Form 314 FM STATION APPLICATIONS FOR ASSIGNMENT OF LICENSE ACCEPTED FOR FILING WV BALH-20170509AAC WCLG-FM 6553 BOWERS BROADCASTING Voluntary Assignment of License CORPORATION E 100.1 MHZ From: BOWERS BROADCASTING CORPORATION WV , MORGANTOWN To: AJG CORPORATION Form 314 Page 1 of 158 Federal Communications Commission 445 Twelfth Street SW PUBLIC NOTICE Washington, D.C. 20554 News media information 202 / 418-0500 Recorded listing of releases and texts 202 / 418-2222 REPORT NO. -

Amerikos Žinios DURYS ATSIDARO

• UTHŪAKUI? wmaY #1 "DRAUGAS"! rOUSBCa £TCTJ TLlu'Sua/, UEBgB, uL \ SUBSCRIFTKKf BAT£3t Foreign Coantrie* - » - $3.00 J — ? ADYEnTCIK UJU M tfLtCJlTTOI AI DRAUGAS PUB. Coi? 1181 W, 46ū $frwi Slisip, S1 į temo. CHICAGO, l L L., KETVIRTADIENIS, 21 DIENA RŪGS, (S EPT E M B E R), 1 9 1 5. iVo.39 M ENTEEED AS SECOND CLASS MATTEB JTJLY Sth, ĮSI2 AT THB fOST OFFICE AT CHICAGO, LLL., UNDER THE ACT OF MARCB 3r3, 1897. LIETUVAI AUTONOMIJOS Amerikos Žinios DURYS ATSIDARO. jurininku sunkiai pažeista. I AUSTRIJOS PASIUNTINIS Maištininkai sugadino Goriai* SKUNDŽIASI. ves miesto vandens trubas. Suv. Viena iš -džiuginančių žinių fe-ydamies turės atsizveisrti a- Valstijų jūreiviai ėmėsi tas tru* liame liūdesio laiku benebus pie Lietuvai autonomijos su -tTM m 11 n daktaras .Austrijos pasiuntimą kas labai nepatik* Rusijos Burnos šalip kitokių teikimą. 1 oas laisvu, Kas Konstantinas Dumba pasiunt' - ant reikalavimų, pareikalavimas haitieeiams ir j izpuoie RuoSkimes ir mes prie to, Suvienyrųju Valstijų sekretoriui Lietuvai autonomijos. Lig kareivių. rengime dirvą. Drąsiau ir Lansmgui laišką, kuriame nuro kiek ji yra mums svarbi, ga do, jog >uv. Valstijų valdžia ne Dabartiniu lai mums patiems pasirodyti su lt kiekvienas numanyti, kurs turi jokio pamato jo pašalinimui jo apieliiikėse uesn^:Uui i nen i viė. savais reikalavimai. Ypač at- plačiau į visą dalyką pa- nuo užimamos vietos D-ras Dum kreijkkne aki \ rengiamąją no maištininko. •V—:--' ^-™^-_ ba savo persergėjimą Austrijos wel|p. Džiaugdavomės, veik lietuvių peticiją būsimam „jErikšteudavonae, jei kokiame pavaldiniams kad jie nedirbtų taikos kongresui. Pirma ginklu dirbtuvėse, gaminančios^ nors iš žymesnių svetimtaučių gal abejojome apie jos amuniciją talkininkams, aiškina - IsdSražčių tilpdavo straipsnio MIRĖ KATALIKŲ VYSKUPAS, pasisekimą. -

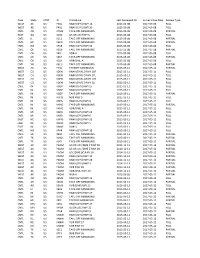

Area State CTRY ID Procedure Last Reviewed on Current Due Date Review Type WEST AK US PAVL RNAV (GPS) RWY 12 2015-05-08 2017-05

Area State CTRY ID Procedure Last Reviewed On Current Due Date Review Type WEST AK US PAVL RNAV (GPS) RWY 12 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 FULL WEST AK US PAVL RNAV (GPS) RWY 30 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 FULL CNTL AR US K7M4 TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 PARTIAL EAST GA US KCSG ILS OR LOC RWY 6 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 FULL CNTL IL US K1C1 TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 PARTIAL CNTL MI US K6G0 TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 PARTIAL CNTL ND US KFAR RNAV (GPS) RWY 36 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 FULL CNTL OH US K3G6 TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 PARTIAL CNTL OH US K4I9 VOR-A 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 FULL CNTL OK US K6K4 TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 PARTIAL CNTL OK US KCLK VOR/DME-A 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 FULL CNTL WI US K3CU TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-08 2017-05-08 PARTIAL WEST AK US PAVL TAKEOFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 PARTIAL WEST CO US KDEN RNAV (RNP) Z RWY 16R 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL WEST CO US KDEN RNAV (RNP) Z RWY 17L 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL WEST CO US KDEN RNAV (RNP) Z RWY 17R 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL WEST CO US KDEN RNAV (RNP) Z RWY 26 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL CNTL IN US KGGP RNAV (GPS) RWY 27 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL CNTL IN US KGGP RNAV (GPS) RWY 9 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL CNTL IN US KGGP TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 PARTIAL CNTL IN US KHHG NDB RWY 9 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL CNTL IN US KHHG RNAV (GPS) RWY 9 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL CNTL IN US KHHG TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 PARTIAL CNTL IN US KHHG VOR/DME-A 2015-05-11 2017-05-11 FULL CNTL MI US KARB RNAV (GPS) -

Lonelecn Asbbkb Kvcmm Ebtirim

f THE OT. J NEWS XOI.UMF. XXV—NO. 36 8T. jcmm, MCHIOAW. THURSDAY a. in4. ONE DCMXAR A YBAR k mkvmmmm nuiML Baekwanl. tora kaskvard. ok, Tim* la jroiir tlsbt: glY* u* a hmM* PBOIAT. •n wlUi sklrta oat ao tlsht; cN* u* a aSBBKB KVCMm girl whoa* ehanas, laaaY or foar. as* O Who «nil remaaiber to keep a # Boi ao expooad by maeb p**b a boo; # faw oMMnaata sfieace at aooa. ao # glv* no a Bialdoa aa matfr what aa*. Rt matter where you nsay be. la de* ^ # voat reaMmbraace ct Hie Croaa EBTIRim wbo woat uM tho atro*t for a raad* lonELEcn 4 and Paeeloa? Ig it aathlag to 4 Till* glYaaaaglrl not so sharp 4 you. all ye that paaa hr? BahoM 4l jaaiAff ly la tI*w. drooa bar la ahlrta tte BATH TBWIHMilP ■AMBN TBAINIB PINB im BhfB BBBfl DPVINI PABBM Wm rSALM MPBATh WABD POB ■ua caaaot shtao through; aad glr* 4 aad aee If there be any aarrow 4 .mm iPAHm. 4 llbe unto my eorrow. ” "Btamad 4| AT MFIIBAT. ■ATBB. us th« daaoos of daya aow gnM by. •P WBBBffBBH. with piracy of clochoo aad slopo aot 4 Harknir. who at tbla boar dMat 4 . — '' so hl^: put turhoy-troc oapors aad 4 haag upon the Croaa. stretching 4 t,rnr sas___________ 4 forth Thy loving arms, grant that 4 IKnL M |Ik ieIB |i IV ri riITgn Tonfiimi ^uu«nollk glMoa, th* burdygurdy Donanain nnn ’ llll^ lt*uXuitU liUMHi “f mMCSBIlul Ulu I iMc CELEWIflOII BEBIB EHRLT 4 all manktad may look unto Thee 4 M I IK ILNn 11 oth*r such baaay-huga, all oa a I*y *I, 4 aad be aaved." 4 . -

G Iid WANDELL REPUBLICAN PRIMARY TUESDAY, SEPT, 11Th .Es COFFEE HOUSE State Plans Extra Xquiz Ofruo

" .-WT, ■ > V ‘- ^1: ' ' 1' ■'■ I rf t r 1'. ?.<- '' ,1. .X "' - at. SATUlTDAt,: SEPTEMBER 8, 19W X AveragM^Hp PrcM Run X. i^ndtjeater iEnanlng -X ■.V.-,,. ’ -For the Woekv^Epded ^ FereeSlt at V. •t..l.'lD56- ' V - X. X: ^'Not BO cool 'iealght.' ihg the town's excellent new Hlgb T w o . school, w* must note it is not with, Cotttmet Signed fo r New Regioiud .Schtsol 1,823 x ; 56.' Tnooday, ehsaeo out minor'Slip-ups.. hCeailMXf'Uie Audit Rgfet' a h o w ^ deairUig : .1 J? ■- But the classic one'--|s fileJ Sc1|Ooj[ of Kur»iiig<; 1 otxartreolatlon afternoon. High anmad 76. Heard' Along Main.:StFeet petition they won't* be able to .un X /■ « t the 'V.v • V-, • ‘ ‘'x ■ , ‘ fold until toe light fixtrue is n^oved. City d f Village Charm ^ Cbmmtmlty SepUet t«>urch w-lH -Miw Jgifla Koriedh. 1814 Bissau —ir— ^Bt;, end Carpt-X^. Mlehaud, 62 Nor- V 'jmeet Tomd^y^ ® * P ^ ^ At^ Qn Somi of MancheUei^t Side Streets, Too : ' Interviewed Is Utolsnd »t t t » home ef Mr*. George Itobm- . A recent- copy of the . Belfast \^U''enter the Wkterbury LXXV, NO. 290 (SiXl^EN PAGESy MANCHESTER, CONN., M ON^Y, SEmM BER tO, 1959 (CUmflaR ertlallig m Pag* 14) PRICE .IP ^ C E M gM , ji3 Deepwoed Dr^ On the Hememadei Sipw Beetrictieae -ynumeiicei designation,, for the gov Weekly Tsiegrsph which reached' H o ^ a i Schiol ©( Nursing on SatM d*y end Ume, the group h( We received a communication emment' before making wine;- and QUr desk pontaj^ an itent in the jdpnday. -

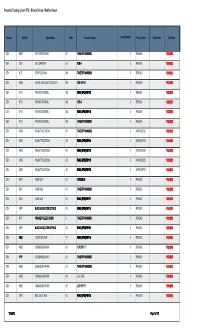

Procedure Tracking System (PTS) - Biennial Review - Workflow Report

Procedure Tracking System (PTS) - Biennial Review - Workflow Report Branch ICAO IDAirport Name State Procedure Name Amend Number Project Satus Review Date Due Date CEN KHSR HOT SPRINGS MUNI SD TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 0 PENDING 10/15/2013 CEN KJSV SALLISAW MUNI OK NDB-A 0 PENDING 10/16/2013 CEN KLJF LITCHFIELD MUNI MN TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 0 PENDING 10/18/2013 CEN KMZH MOOSE LAKE CARLTON COUNTY MN NDB RWY 04 0 PENDING 10/21/2013 CEN KFYG WASHINGTON RGNL MO RNAV (GPS) RWY 33 0 PENDING 10/22/2013 CEN KFYG WASHINGTON RGNL MO VOR-A 0 PENDING 10/22/2013 CEN KFYG WASHINGTON RGNL MO RNAV (GPS) RWY 15 0 PENDING 10/22/2013 CEN KFYG WASHINGTON RGNL MO TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 0 PENDING 10/22/2013 CEN KARG WALNUT RIDGE RGNL AR TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 0 IN PROGRESS 10/31/2013 CEN KARG WALNUT RIDGE RGNL AR RNAV (GPS) RWY 36 0 IN PROGRESS 10/31/2013 CEN KARG WALNUT RIDGE RGNL AR RNAV (GPS) RWY 04 0 IN PROGRESS 10/31/2013 CEN KARG WALNUT RIDGE RGNL AR RNAV (GPS) RWY 18 0 IN PROGRESS 10/31/2013 CEN KARG WALNUT RIDGE RGNL AR RNAV (GPS) RWY 22 0 IN PROGRESS 10/31/2013 CEN KMIO MIAMI MUNI OK VOR/DME-A 0 PENDING 10/31/2013 CEN KMIO MIAMI MUNI OK TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 0 PENDING 10/31/2013 CEN KMIO MIAMI MUNI OK RNAV (GPS) RWY 17 0 PENDING 10/31/2013 CEN KSPF BLACK HILLS-CLYDE ICE FIELD SD RNAV (GPS) RWY 13 0 PENDING 10/31/2013 CEN KPJY PINCKNEYVILLE-DU QUOIN IL TAKE-OFF MINIMUMS 0 PENDING 10/31/2013 CEN KSPF BLACK HILLS-CLYDE ICE FIELD SD RNAV (GPS) RWY 31 0 PENDING 10/31/2013 CEN K6R3 CLEVELAND MUNI TX RNAV (GPS) RWY 16 0 PENDING 10/31/2013 CEN KHSD SUNDANCE AIRPARK OK VOR RWY 17 0 -

A Grammar of Jahai

A grammar of lahai PacificLinguistics REFERENCE COpy Not to be removed Burenhult, N. A grammar of Jahai. PL-566, xiv + 245 pages. Pacific Linguistics, The Australian National University, 2005. DOI:10.15144/PL-566.cover ©2005 Pacific Linguistics and/or the author(s). Online edition licensed 2015 CC BY-SA 4.0, with permission of PL. A sealang.net/CRCL initiative. Pacific Linguistics 566 Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, East Timor, southeast and south Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant fr om the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Publications are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise, who are usually not members of the editorial board. FOUNDINGEDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: John Bowden, Malcolm Ross and Darrell Tryon (Managing Editors), I Wayan Arka, David Nash, Andrew Pawley, Paul Sidwell, Jane Simpson EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Karen Adams, Arizona State University Lillian Huang, National Taiwan Normal Peter Austin, School of Oriental and African University Studies Bambang Kaswanti Purwo, Universitas Atma Alexander Adelaar, University of Melbourne Jaya Byron Bender, University of Hawai 'i Marian Klamer, Universiteit -

Aloe'''io in the \Iatter 01' MAR 2 G ZOOZ L'tilifllai

OOCKET FILE COPY ORIGINAl Before the Federal Communications Commission Washington, D.C. 20554 Aloe'''IO In the \Iatter 01' MAR 2 G ZOOZ l'tilIfllAI. ~I'" ",,,_ Rules and Policies Concerning MI!JE fE lItE SB:IlETAAr \Iultiple Ownership orRadio Broadcast .\1\1 Docket No. 01-317 Stations in Local Markets Dctinition or Radio Markets \Il'vl Docket No. 00-244 COMMENTS OF TIlE OFFICE OF COMMUNICATION, INC. OF TIlE UNITED CHURCH OF CHRIST Of Counsel: Christopher R. Day Angela 1. Campbell Institute for Public Representation Janelle Hu, Law Student Georgetown University Law Center Georgetown University Law Center 600 New Jersey Avenue, N.W. Suite 312 Washington, D.C. 20001 Phone: (202) 662-9535 Dated: March 27, 2002 ------------ SL:\L\I.\RY The Omee ol"Communieation, fnL of the Lnited Church of Christ ("LCC") is extremely C<lnccrned ahoutlhe massivc consolidation that has <lccurred in many local radio markets in rceent years. ;\s detailed helmv, diversity and c<lmpditi<ln have declined dramatically in m'II1\' l<lealradio markets. Furthermore, the ('ommlssi<ln and the DO.!'s "case-hy-case" analysis 01' many mergers has ,'ailed to protect diversity or serve the public IIltercst. Accordingly, UCC urges the Commission to adopt a "hright-line" test Illr radio mergers in order to protect the puhlic interest. while ensuring that radio l11cr~crs arc rroccsscd in a expeditious manner. III response 10 the Commission rClJuest Il)r methods to measure the characteristics of [<leal radi<l markets, LJCC urges the Commission to analyze diversity and competition in local radio markets hy counting the numher of inderendently-owned radio stations within the geograrhie houndaries of local Arhitron ,vktro Markets. -

File: 2008 2108Tawschanges.Txt 7/27/2021, 5:10:12 PM TAWS

File: 2010_2110TAWSChanges.txt 9/21/2021, 3:07:49 PM TAWS Airport Database comparison between Cycle 2010 and 2110. Region APT_ID AIRPORT_NAME Difference ________________________________________________________________________________ AFR DAAP TAKHAMALT Airport Changed AFR DAAP TAKHAMALT Runway RW09 Changed AFR DAAP TAKHAMALT Runway RW27 Changed AFR DAAT AGUENAR-HADJ BEY AKHAMOK Runway RW08 Changed AFR DAAT AGUENAR-HADJ BEY AKHAMOK Runway RW26 Changed AFR DAAV FERHAT ABBAS Airport Changed AFR DAAV FERHAT ABBAS Runway RW17 Changed AFR DAAV FERHAT ABBAS Runway RW35 Changed AFR DAOF TINDOUF Airport Changed AFR DAOF TINDOUF Runway RW08L Changed AFR DAOF TINDOUF Runway RW08R Changed AFR DAOF TINDOUF Runway RW26L Changed AFR DAOF TINDOUF Runway RW26R Changed AFR DAON ZENATA-MESSALI EL HADJ Runway RW07 Changed AFR DAON ZENATA-MESSALI EL HADJ Runway RW25 Changed AFR DAOY EL BAYADH Runway RW04 Changed AFR DAOY EL BAYADH Runway RW22 Changed AFR DAUK SIDI MAHDI Runway RW01 Changed AFR DAUK SIDI MAHDI Runway RW19 Changed AFR DAUU AIN BEIDA Airport Changed AFR DAUU AIN BEIDA Runway RW18 Changed AFR DAUU AIN BEIDA Runway RW36 Changed AFR DBBB CARDINAL BERNARDIN GANTIN INTL Airport Changed AFR DBBB CARDINAL BERNARDIN GANTIN INTL Runway RW06 Changed AFR DBBB CARDINAL BERNARDIN GANTIN INTL Runway RW24 Changed AFR DFFD OUAGADOUGOU Airport Changed AFR DFFD OUAGADOUGOU Runway RW04 Changed AFR DFFD OUAGADOUGOU Runway RW22 Changed AFR DGAA KOTOKA INTL Runway RW03 Changed AFR DGAA KOTOKA INTL Runway RW21 Changed AFR DGAH HO Airport Added AFR DGAH HO Runway RW04 -

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27

1 HANSON BRIDGETT LLP NEAL L. WOLF, SBN 202129 2 [email protected] ANTHONY J. DUTRA, SBN 277706 3 [email protected] 425 Market Street, 26th Floor 4 San Francisco, California 94105 Telephone: (415) 777-3200 5 Facsimile: (415) 541-9366 6 Proposed Attorneys for Debtors and Debtors in Possession 7 8 UNITED STATES BANKRUPTCY COURT 9 NORTHERN DISTRICT OF CALIFORNIA 10 OAKLAND DIVISION 11 12 In re Case Nos. 20-40857 (RLE) 13 20-40858 (RLE) GALILEO LEARNING, LLC, 14 Chapter 11 15 Debtor.1 (Jointly Administered) 16 DEBTORS’ APPLICATION SEEKING In re ENTRY OF AN ORDER (I) AUTHORIZING 17 THE RETENTION AND EMPLOYMENT GALILEO LEARNING FRANCHISING OF HANSON BRIDGETT LLP AS THE 18 LLC, DEBTORS’ COUNSEL PURSUANT TO SECTION 327(a) OF THE BANKRUPTCY 19 CODE AND BANKRUPTCY RULES Debtor. 2014(a) AND 2016, RETROACTIVE TO 20 MAY 6, 2020; AND (II) GRANTING RELATED RELIEF 21 22 23 24 25 26 1 These cases are being jointly administered, and all documents for either case should be filed in lead case number 20-40857 (RLE). The last four digits of each Debtor’s 27 federal tax identification number, are as follows: Galileo Learning, LLC (9453) and Galileo 28 Learning Franchising LLC (5638). The mailing address for the Debtors is 1021 3rd Street, Oakland, CA 94607. 16535810.1Case: 20-40857DEBTORS ’ APPLICATIONDoc# 69 Filed: TO EMPLOY 06/03/20 HANSON Entered: BRIDGETT 06/03/20 LLP AS17:05:49 THE DEBTORS Page’ 1COUNSEL of 82 1 Galileo Learning, LLC (“Galileo Learning”) and Galileo Learning Franchising, LLC, 2 (“Galileo Franchising”), debtors and debtors in possession (collectively, the “Debtors”) in 3 the above-captioned chapter 11 cases (the “Chapter 11 Cases”), seek entry of an order 4 (the “Order”), substantially in the form attached hereto as Exhibit A, (i) appointing Hanson 5 Bridgett LLP (“Hanson”), as legal counsel for the Debtors in their Chapter 11 Cases 6 effective as of May 6, 2020 (the “Petition Date”); and (ii) granting related relief. -

ACW Network Delivery List the Air Culinaire Worldwide Network Services the Following Locations for In-Flight Catering

ACW Network Delivery List The Air Culinaire Worldwide Network services the following locations for in-flight catering. To view our interactive map, please visit www.airculinaireworldwide.com/map AFRICA HESN Aswan NamibiaACW_pref_A_hor_4CP (hor_tag) Algeria Equatorial Guinea FYWE Windhoek DAAB Blida FGSL Malabo FYWH Khomas DAAG Dar El Beida Ethiopia Nigeria DAAS Setif Ain Arnat HAAB Addis Ababa DNAA Nnamdi Azikiwe DAAT Tamanrasset Gabon DNBE Benin DABC Constantine FOOL Libreville DNMM Murtala Mohammed DAOO Oran Ghana Rwanda Angola DGAA Accra HRYR Kigali FNLU Luanda Kenya São Tomé and Príncipe Botswana HKJK Nairobi FPST São Tomé Island FBKE Kasane Liberia Senegal FBMN Maun GLMR Monrovia GOOY Dakar FBSK Gaborone GLRB Harbel Seychelles Burkina Faso Malawi FSIA Seychelles DFFD Ouagadougou FWCL Blantyre FACT Cape Town Cameroon Mauritania FAGC Midrand FKKD Douala GQNN Nouakchott FAGG George Cape Verde Mauritius FAGM Johannesburg GVAC Espargos FIMP Plaine Magnien FALA Lanseria Chad Morocco FALE La Mercy FTTJ N’Djamena GMAA Agadir FAOR Johannesburg Congo GMAD Agadir FAWK Pretoria FCBB Brazzaville GMAT Tan Tan FAYP Cape Town FCPP Pointe-Noire GMFF Fes South Africa FZAA Kinshasa GMFK Errachidia FAGC Midrand Cote D’Ivoire GMFO Oujda FANS Nelspruit DIAP Abidjan GMME Rabat–Salé FALE La Mercy Egypt GMMH Dakhla FAYP Cape Town HEAL Al Alamein GMMI Essaouira FACT Cape Town HEBA Alexandria GMMN Nouasseur FALA Lanseria HEBL Abu Simbel GMMW Al-Aroui FAOR Johannesburg HECA Cairo GMMX Marrakesh FAWK Pretoria HETB South Sinai Governorate GMMZ Ouarzazate Tanzania HEGN Hurghada GMTN Tetouan HTDA Dar Es Salaam HELX Luxor GMTT Boukhalef HTKJ Kilimanjaro HEMA Marsa Alam Mozambique Togo HESH Sharm El Sheikh FQMA Maputo DXXX Lome To Order: N.