ABSTRACT CAMELOT, OHIO by Will Conroy This Collection of Short

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Characteristics Do All Invasive Species Share That Make Them So

Invasive Plants Facts and Figures Definition Invasive Plant: Plants that have, or are likely to spread into native or minimally managed plant systems and cause economic or environmental harm by developing self-sustaining populations and becoming dominant or disruptive to those systems. Where do most invasive species come from? How do they get here and get started? Most originate long distances from the point of introduction Horticulture is responsible for the introduction of approximately 60% of invasive species. Conservation uses are responsible for the introduction of approximately 30% of invasive species. Accidental introductions account for about 10%. Of all non-native species introduced only about 15% ever escape cultivation, and of this 15% only about 1% ever become a problem in the wild. The process that leads to a plant becoming an invasive species, Cultivation – Escape – Naturalization – Invasion, may take over 100 years to complete. What characteristics make invasive species so successful in our environment? Lack predators, pathogens, and diseases to keep population numbers in check Produce copious amounts of seed with a high viability of that seed Use successful dispersal mechanisms – attractive to wildlife Thrive on disturbance, very opportunistic Fast-growing Habitat generalists. They do not have specific or narrow growth requirements. Some demonstrate alleleopathy – produce chemicals that inhibit the growth of other plants nearby. Have longer photosynthetic periods – first to leaf out in the spring and last to drop leaves in autumn Alter soil and habitat conditions where they grow to better suit their own survival and expansion. Why do we care? What is the big deal? Ecological Impacts Impacting/altering natural communities at a startling rate. -

Lasting-Love-At-Last-By-Amari-Ice.Pdf

Lasting Love at Last The Gay Guide to Attracting the Relationship of Your Dreams By Amari Ice 2 Difference Press McLean, Virginia, USA Copyright © Amari Ice, 2017 Difference Press is a trademark of Becoming Journey, LLC All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the author. Reviewers may quote brief passages in reviews. Published 2017 ISBN: 978-1-68309-218-6 DISCLAIMER No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical or electronic, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, or transmitted by email without permission in writing from the author. Neither the author nor the publisher assumes any responsibility for errors, omissions, or contrary interpretations of the subject matter herein. Any perceived slight of any individual or organization is purely unintentional. Brand and product names are trademarks or registered trademarks of their respective owners. Cover Design: Jennifer Stimson Editing: Grace Kerina Author photo courtesy of Donta Hensley (photographer), Jay Lautner (editor) 3 To My Love: Thank you for being unapologetically and unwaveringly you, and for being a captive audience for my insatiably playful antics. #IKeep 4 Table of Contents Foreword 6 A Note About the #Hashtags 8 Introduction – Tardy for the Relationship Party 9 Chapter 1 – #OnceUponATime 16 Chapter 2 – What’s Mercury Got to Do with It? 23 Section 1 – Preparing: The Realm of #RelationshipRetrograde 38 Chapter -

Copyrighted Material

PART ON E F IS FOR FORTUNE COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL CCH001.inddH001.indd 7 99/18/10/18/10 77:13:28:13:28 AAMM CCH001.inddH001.indd 8 99/18/10/18/10 77:13:28:13:28 AAMM LOST IN LOST ’ S TIMES Richard Davies Lost and Losties have a pretty bad reputation: they seem to get too much fun out of telling and talking about stories that everyone else fi nds just irritating. Even the Onion treats us like a bunch of fanatics. Is this fair? I want to argue that it isn ’ t. Even if there are serious problems with some of the plot devices that Lost makes use of, these needn ’ t spoil the enjoyment of anyone who fi nds the series fascinating. Losing the Plot After airing only a few episodes of the third season of Lost in late 2007, the Italian TV channel Rai Due canceled the show. Apparently, ratings were falling because viewers were having diffi culty following the plot. Rai Due eventually resumed broadcasting, but only after airing The Lost Survivor Guide , which recounts the key moments of the fi rst two seasons and gives a bit of background on the making of the series. Even though I was an enthusiastic Lostie from the start, I was grateful for the Guide , if only because it reassured me 9 CCH001.inddH001.indd 9 99/18/10/18/10 77:13:28:13:28 AAMM 10 RICHARD DAVIES that I wasn’ t the only one having trouble keeping track of who was who and who had done what. -

Time Travel and Free Will in the Television Show Lost

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Directory of Open Access Journals Praxes of popular culture No. 1 - Year 9 12/2018 - LC.1 Kevin Drzakowski, University of Wisconsin-Stout, USA Paradox Lost: Time Travel and Free Will in the Television Show Lost Abstract The television series Lost uses the motif of time travel to consider the problem of human free will, following the tradition of Humean compatibilism in asserting that human beings possess free will in a deterministic universe. This paper reexamines Lost’s final mystery, the “Flash Sideways” world, presenting a revisionist view of the show’s conclusion that figures the Flash Sideways as an outcome of time travel. By considering the perspectives of observers who exist both within time and outside of it, the paper argues that the characters of Lost changed their destinies, even though the rules of time travel in Lost’s narrative assert that history cannot be changed. Keywords: Lost, time travel, Hume, free will, compatibilism My purpose in this paper is twofold. First, I intend to argue that ABC’s Lost follows a tradition of science fiction in using time travel to consider the problem of human free will, making an original contribution to the debate by invoking a narrative structure previously unseen in time travel stories. I hope to show that Lost, a television show that became increasingly invested in questions over free will and fate as the series progressed, makes a case for free will in the tradition of Humean compatibilism, asserting that human beings possess free will even in a deterministic world. -

Weed Control Guide for Ohio, Indiana and Illinois

Pub# WS16 / Bulletin 789 / IL15 OHIO STATE UNIVERSITY EXTENSION Tables Table 1. Weed Response to “Burndown” Herbicides .............................................................................................19 Table 2. Application Intervals for Early Preplant Herbicides ............................................................................... 20 Table 3. Weed Response to Preplant/Preemergence Herbicides in Corn—Grasses ....................................30 WEED Table 4. Weed Response to Preplant/Preemergence Herbicides in Corn—Broadleaf Weeds ....................31 Table 5. Weed Response to Postemergence Herbicides in Corn—Grasses ...................................................32 Table 6. Weed Response to Postemergence Herbicides in Corn—Broadleaf Weeds ..................................33 2015 CONTROL Table 7. Grazing and Forage (Silage, Hay, etc.) Intervals for Herbicide-Treated Corn ................................. 66 OHIO, INDIANA Table 8. Rainfast Intervals, Spray Additives, and Maximum Crop Size for Postemergence Corn Herbicides .........................................................................................................................................................68 AND ILLINOIS Table 9. Herbicides Labeled for Use on Field Corn, Seed Corn, Popcorn, and Sweet Corn ..................... 69 GUIDE Table 10. Herbicide and Soil Insecticide Use Precautions ......................................................................................71 Table 11. Weed Response to Herbicides in Popcorn and Sweet Corn—Grasses -

Chapter 9 Page 1 of 40 02/25/2020 Ord. 865

CHAPTER 9 ORDERLY CONDUCT, PUBLIC NUISANCE, HEALTH AND SANITATION 9.01 Intent and Purpose 9.02 Public Nuisance Defined 9.03 Health Department 9.04 Abatement of Health Nuisances 9.05 Rules and Regulations 9.06 Communicable Diseases 9.07 Public Nuisances Affecting Health and Welfare (1) Adulterated and Unsafe Food (2) Unburied Carcasses (3) Breeding Places for Vermin, etc. (4) Water Pollution (5) Noxious Odors, etc. (6) Street Pollution (7) Air Pollution (8) Surface Waters Prohibited in the Sewage Disposal System (9) Noise Pollution, Regulation of Excessive Noise, Loud and Unnecessary Noise Prohibited (10) Offensive Industries (11) Property Maintenance, Vehicle Parking, Storage and Non Abandonment Code (12) Recycling, Compost, Garbage and Rubbish Removal Standards 9.08 Public Nuisances Offending Morals and Decency (1) Obscene Materials, Devices or Performances (2) Prostitution Prohibited (3) Disorderly Houses Prohibited (4) Gambling, Lotteries, Fraudulent Devices and Practices Prohibited (5) Alcohol and Drug Restrictions (6) Prohibition Against Possession Of Marijuana (7) Prohibition of the Sale, Possession, Manufacture, Delivery And Advertisement of Drug Paraphernalia 9.09 Public Nuisances Affecting Peace and Safety (1) Discharging and Carrying Firearms and Guns; Prohibitions (2) Throwing or Shooting of Arrows, Stones and Other Missiles Prohibited (3) Disorderly Conduct Prohibited (4) Alarm System Requirements and False Alarms Prohibited (5) Obedience to Officers (6) Destruction of Property Prohibited (7) Regulations Regarding School Property (8) Truancy Prohibited (9) Loitering Prohibited (10) Loitering of Minors (11) Civil Trespass (12) Theft or Retaining Possession of Library Materials Chapter 9 Page 1 of 40 02/25/2020 Ord. 865 (13) Illegal Buildings (14) Dangerous Trees and Tree Limbs (15) Regulation of Fireworks (16) Animals or Fowl (17) Obstruction of Streets, Sidewalks, and Public Spaces (18) Distribution of Handbills Prohibited (19) Open Cisterns, Wells, Basements Or Other Dangerous Excavations Prohibited. -

Arctotheca Prostrata (Asteraceae: Arctotideae), a South African Species Now Present in Mexico

Botanical Sciences 93 (4): 877-880, 2015 TAXONOMY AND FLORISTICS DOI: 10.17129/botsci.223 ARCTOTHECA PROSTRATA (ASTERACEAE: ARCTOTIDEAE), A SOUTH AFRICAN SPECIES NOW PRESENT IN MEXICO OSCAR HINOJOSA-ESPINOSA1,2,3 Y JOSÉ LUIS VILLASEÑOR1 1Instituto de Biología, Departamento de Botánica, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México, D. F. 2Facultad de Ciencias, Departamento de Biología Comparada, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, México D.F. 3Corresponding author: [email protected] Abstract: Arctotheca prostrata is a South African species that has been introduced in other parts of the world, such as California and Australia. Here we report the presence of A. prostrata for the fi rst time in Mexico. To date we have detected the species in nine sites south of Mexico City. The species shows weedy tendencies at each site. It is possible that A. prostrata arrived to Mexico through horticulture and later escaped from cultivation. This species needs to be included in the list of Mexican prohibited weeds, thus permitting the implementation of preventive strategies to avoid its spreading in the country. Key words: Arctotidinae, escaped from cultivation, introduced weeds, South African weeds. Resumen: Arctotheca prostrata es una especie sudafricana que se encuentra introducida en otras partes del mundo, tales como California y Australia. En este artículo se da a conocer por primera vez la presencia de A. prostrata en México. Hasta el momento la especie se ha detectado en nueve sitios al sur de la Ciudad de México. En cada localidad, la especie se comporta como maleza. Es posible que A. prostrata haya llegado a México a través de la horticultura y posteriormente escapara de cultivo. -

History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Ireland Since 1840

Brigham Young University BYU ScholarsArchive Theses and Dissertations 1968 History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Ireland Since 1840 Brent A. Barlow Brigham Young University - Provo Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd Part of the European History Commons, History of Christianity Commons, and the Mormon Studies Commons BYU ScholarsArchive Citation Barlow, Brent A., "History of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints in Ireland Since 1840" (1968). Theses and Dissertations. 4503. https://scholarsarchive.byu.edu/etd/4503 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by BYU ScholarsArchive. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of BYU ScholarsArchive. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. 4119 HISTORY OF THE CHURCH OF JESUS CHRIST OF UTTERUTTERDAYLATTERDAYLATTER DAY SAINTS IN IRELANDD SINCE 18101840 A thesis presented to the department of graduate studies in religious instruction brigham young university provo utah in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree master of arts by brent aaAa& barlow may 1968 acknowledgments I1 would like to express ravmyraysincere appreciation to the following people for thetheirir valuable assistance and help dr richard 0 cofanocowanocowan chairman of the advisory colitcomitcommitteetee fforroror his many timely suggestions and genuine interest in this research pro- ject dr rodney turner member of the advisory committee -

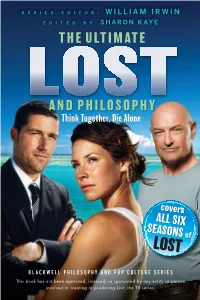

The Ultimate and Philosophy

PHILOSOPHY/POP CULTURE IRWIN SERIES EDITOR: WILLIAM IRWIN What are the metaphysics of time travel? EDITED BY SHARON KAYE How can Hurley exist in two places at the same time? THE ULTIMATE What does it mean for something to be possibly true in the fl ash-sideways universe? Does Jack have a moral obligation to his father? THE ULTIMATE What is the Tao of John Locke? Dude. So there’s, like, this island? And a bunch of us were on Oceanic fl ight 815 and we crashed on it. I kinda thought it was my fault, because of those numbers. I thought they were bad luck. We’ve seen the craziest things here, like a polar bear and a Smoke Monster, and we traveled through time back to the 1970s. And we met the Dharma dudes. Arzt even blew himself up. For a long time, I thought I was crazy. But now, I think it might have been destiny. The island’s made me question a lot of things. Like, why is it that Locke and Desmond have the same names as real philosophers? Why do so many of us have AND PHILOSOPHY trouble with our dads? Did Jack have a choice in becoming our leader? And what’s up Think Together, Die Alone with Vincent? I mean, he’s gotta be more than just a dog, right? I dunno. We’ve all felt pretty lost. I just hope we can trust Jacob, otherwise . whoa. With its sixth-season series fi nale, Lost did more than end its run as one of the most AND PHILOSOPHY talked-about TV programs of all time; it left in its wake a complex labyrinth of philosophical questions and issues to be explored. -

Internetsownboy Transcri

[Music] >>A cofounder of the social, news and entertainment website Reddit has been found dead. >>He certainly was a prodigy, although he never kind of thought of himself like that. >>He was totally unexcited about starting businesses and making money. >>There's a profound sense of loss tonight in Highland Park, Aaron Swartz's hometown, as loved ones say goodbye to one of the Internet's brightest lights. >>Freedom, open access, and computer activists are mourning his loss. >>An astonishing intellect, if you talk to people who knew him. >>He was killed by the government, and MIT betrayed all of its basic principles. >>They wanted to make an example out of him, okay? >>Governments have an insatiable desire to control. >>He was potentially facing 35 years in prison and a one million dollar fine. >>Raising questions of prosecutorial zeal, and I would say even misconduct. Have you looked into that particular matter and reached any conclusions? >>Growing up, you know, I slowly had this process of realizing that all the things around me that people had told me were just the natural way things were, the way things always would be. They weren't natural at all, they were things that could be changed and they were things that, more importantly were wrong and should change. And once I realized that, there was really kind of no going back. >>Welcome to story reading time. The name of the book is "Paddington at the Fair". >>Well, he was born in Highland Park and grew up here. Aaron came from a family of three brothers, all extraordinarily bright. -

WHY DIVERSITY IS GOOD for Intentional Community by Kara Huntermoon

Power, Gender, Class, and Race WHY DIVERSITY IS GOOD for Intentional Community By Kara Huntermoon Eight Heart-Culture Farm Community children, ranging in age from two to 13. hy is diversity good for intentional communities? Challeng- beaten until they complied. While these laws have been repealed, and ing systems of oppression takes place on all levels, from the today Oregon is known as a liberal state, we are still living in strongly micro to the macro. Understanding the macro dynamics, the segregated communities. White liberal people have little opportunity patternsW of the wider society, lends significance to interactions on the to learn, through relationships with people of color, about their own personal level. The work of linking the macro to the micro can help privilege and racism. This leads to a kind of white denial, where we are us make personal choices that affect our bigger society. In my life, as a genuinely liberal and anti-racist, but unaware of our own privilege, so white woman in an intentional community in Oregon, I can tie these we perpetuate the institutions of racism without even knowing it. levels together through three vignettes from different levels of reality: Intentional communities in Oregon are generally white dominated macro (Oregon history and politics), micro (personal feelings and rela- and attract mostly white middle class people. If we want to change this tionships), and community-scale (interpersonal decision-making). (and I do!) we have to reach across color lines to create diverse com- munities. For communities to succeed in retaining residents long-term, Macro Level: Oregon History and Politics we have to develop an awareness of the larger societal dynamics that Segregation practices over 500-plus years have succeeded in making affect our personal relationships. -

Jack's Costume from the Episode, "There's No Place Like - 850 H

Jack's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 572 Jack's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 850 H... 300 Jack's suit from "There's No Place Like Home, Part 1" 200 573 Jack's suit from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 950 Home... 300 200 Jack's costume from the episode, "Eggtown" 574 - 800 Jack's costume from the episode, "Eggtown." Jack's bl... 300 200 Jack's Season Four costume 575 - 850 Jack's Season Four costume. Jack's gray pants, stripe... 300 200 Jack's Season Four doctor's costume 576 - 1,400 Jack's Season Four doctor's costume. Jack's white lab... 300 Jack's Season Four DHARMA scrubs 200 577 Jack's Season Four DHARMA scrubs. Jack's DHARMA - 1,300 scrub... 300 Kate's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 578 Kate's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 1,100 H... 300 Kate's costume from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 579 Kate's costume from the episode, "There's No Place Like - 900 H... 300 Kate's black dress from "There's No Place Like Home" 200 580 Kate's black dress from the episode, "There's No Place - 950 Li... 300 200 Kate's Season Four costume 581 - 950 Kate's Season Four costume. Kate's dark gray pants, d... 300 200 Kate's prison jumpsuit from the episode, "Eggtown" 582 - 900 Kate's prison jumpsuit from the episode, "Eggtown." K... 300 200 Kate's costume from the episode, "The Economist 583 - 5,000 Kate's costume from the episode, "The Economist." Kat..