619 the Constant, the Variable, and the Bad Wolf in Lost and Doctor

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

L'équipe Des Scénaristes De Lost Comme Un Auteur Pluriel Ou Quelques Propositions Méthodologiques Pour Analyser L'auctorialité Des Séries Télévisées

Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées Quentin Fischer To cite this version: Quentin Fischer. Lost in serial television authorship : l’équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l’auctorialité des séries télévisées. Sciences de l’Homme et Société. 2017. dumas-02368575 HAL Id: dumas-02368575 https://dumas.ccsd.cnrs.fr/dumas-02368575 Submitted on 18 Nov 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Distributed under a Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial - NoDerivatives| 4.0 International License UNIVERSITÉ RENNES 2 Master Recherche ELECTRA – CELLAM Lost in serial television authorship : L'équipe des scénaristes de Lost comme un auteur pluriel ou quelques propositions méthodologiques pour analyser l'auctorialité des séries télévisées Mémoire de Recherche Discipline : Littératures comparées Présenté et soutenu par Quentin FISCHER en septembre 2017 Directeurs de recherche : Jean Cléder et Charline Pluvinet 1 « Créer une série, c'est d'abord imaginer son histoire, se réunir avec des auteurs, la coucher sur le papier. Puis accepter de lâcher prise, de la laisser vivre une deuxième vie. -

The MULLET RAPPER What’S Happening in the Everglades City Area TIDE TABLE 25¢ RESTAURANTS JAN

The MULLET RAPPER What’s Happening in the Everglades City Area TIDE TABLE 25¢ RESTAURANTS JAN. 28 – FEB. 10, 2017 \ © 2017, K Bee Marketing P O Box 134, Everglades City, FL, 34139 Volume X Issue #281 Art-In-The-Glades Events 2017 Everglades Seafood Festival Schedule of Events! Combine Local Art & Entertainment It’s that time of year again! The annual Everglades Seafood Festival If you have not been to one of the Art- will roll into town for the weekend on Friday February 10th through In-The-Glades events, you’re missing Sunday the 12th. You can expect great foods, unique art, crafts and jewelry out! Local Artists, musicians and and carnival rides for the kids. Music is always a feature, and this year won’t disappoint. Mark your calendars and book your rooms so you don’t miss one day of this great event. Mayor Hamilton greets the crowd in 2016 EVERGLADES SEAFOOD FESTIVAL - 2017 LINEUP Friday, February 10 5:30 pm OPENING CEREMONY 5:45 pm Charlie Pace entrepreneurs have made this a “must 6:30 pm The Lost Rodeo attend” for area residents and visitors. 7:30 pm Let's Hang On Booths are free so be sure to sign up for 9:00 pm Chappell & Chet the next event taking place on Feb. 25th! 9:45 pm Tim Elliott For info call Marya @ 239-695-2905, for more details, see page 3. Saturday, February 11 There is something for everyone to enjoy 10:00 am OPENING CEREMONY National Anthem - Sloan Wheeler 11:00 am Delbert Britton/Ronnie Goff and the Country Hustlers 12:00 pm Them Hamilton Boys 1:00 pm Gator Nate 2:00 pm Garrett Speer 3:15 pm A Thousand Horses 5:30 pm Tim Charron 7:00 pm Tim Elliott 8:30 pm Little Texas Sunday, February 12 11:00 am OPENING CEREMONY Rides for the kids or the “kid in you” National Anthem - Nadia Turner RAPPER TABLE OF CONTENTS 12:00 pm Tim McGeary Calendar p. -

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space With

The Expression of Orientations in Time and Space with Flashbacks and Flash-forwards in the Series "Lost" Promotor: Auteur: Prof. Dr. S. Slembrouck Olga Berendeeva Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde Afstudeerrichting: Master Engels Academiejaar 2008-2009 2e examenperiode For My Parents Who are so far But always so close to me Мои родителям, Которые так далеко, Но всегда рядом ii Acknowledgments First of all, I would like to thank Professor Dr. Stefaan Slembrouck for his interest in my work. I am grateful for all the encouragement, help and ideas he gave me throughout the writing. He was the one who helped me to figure out the subject of my work which I am especially thankful for as it has been such a pleasure working on it! Secondly, I want to thank my boyfriend Patrick who shared enthusiasm for my subject, inspired me, and always encouraged me to keep up even when my mood was down. Also my friend Sarah who gave me a feedback on my thesis was a very big help and I am grateful. A special thank you goes to my parents who always believed in me and supported me. Thanks to all the teachers and professors who provided me with the necessary baggage of knowledge which I will now proudly carry through life. iii Foreword In my previous research paper I wrote about film discourse, thus, this time I wanted to continue with it but have something new, some kind of challenge which would interest me. After a conversation with my thesis guide, Professor Slembrouck, we decided to stick on to film discourse but to expand it. -

Copyrighted Material

PART ON E F IS FOR FORTUNE COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL CCH001.inddH001.indd 7 99/18/10/18/10 77:13:28:13:28 AAMM CCH001.inddH001.indd 8 99/18/10/18/10 77:13:28:13:28 AAMM LOST IN LOST ’ S TIMES Richard Davies Lost and Losties have a pretty bad reputation: they seem to get too much fun out of telling and talking about stories that everyone else fi nds just irritating. Even the Onion treats us like a bunch of fanatics. Is this fair? I want to argue that it isn ’ t. Even if there are serious problems with some of the plot devices that Lost makes use of, these needn ’ t spoil the enjoyment of anyone who fi nds the series fascinating. Losing the Plot After airing only a few episodes of the third season of Lost in late 2007, the Italian TV channel Rai Due canceled the show. Apparently, ratings were falling because viewers were having diffi culty following the plot. Rai Due eventually resumed broadcasting, but only after airing The Lost Survivor Guide , which recounts the key moments of the fi rst two seasons and gives a bit of background on the making of the series. Even though I was an enthusiastic Lostie from the start, I was grateful for the Guide , if only because it reassured me 9 CCH001.inddH001.indd 9 99/18/10/18/10 77:13:28:13:28 AAMM 10 RICHARD DAVIES that I wasn’ t the only one having trouble keeping track of who was who and who had done what. -

Valis Free Ebook

FREEVALIS EBOOK Philip K. Dick | 272 pages | 12 Jul 2001 | Orion Publishing Co | 9781857983395 | English | London, United Kingdom Valis (novel) - Wikipedia Dickit is one book of a three part series. The book features heavy auto-biographical elements, and draws inspiration from Dick's own religious experiences over the Valis decade. The planned third novel, The Valis in Daylighthad not yet taken definite shape Valis the time of the author's death. Pike and Valis, while Valis referencing VALIS directly, is thematically similar; Valis wrote: "the three do form a trilogy constellating around a basic theme. Dick experiences visions of a pink beam of light that he calls Zebra Valis interprets as a theophany exposing hidden facts about the reality of our universe, and a group of others join him in researching these matters. One of their theories is that there is some kind of alien Valis probe in orbit around Earth, and that it is aiding them in their quest; it also aided Valis United States in disclosing the Watergate scandal and the resignation of Richard Nixon in August, Kevin turns his friends on to a film called Valis that contains obvious references to revelations identical to those Valis Horselover Valis has experienced, including what appears to be time dysfunction. The film is itself a fictional account of an Valis version of Nixon "Ferris F. In seeking the film's makers, Kevin, Phil, Fat, and David—now calling themselves the Rhipidon Society—head to an estate owned by popular musician Valis Lampton and his wife Linda. They decide Valis goal that they have been led toward is Sophia Lampton, who is two-years old and the Messiah or incarnation of Holy Wisdom Pistis Sophia anticipated by some variants of Gnostic Christianity. -

LOST the Official Show Auction

LOST | The Auction 156 1-310-859-7701 Profiles in History | August 21 & 22, 2010 572. JACK’S COSTUME FROM THE EPISODE, “THERE’S NO 574. JACK’S COSTUME FROM PLACE LIKE HOME, PARTS 2 THE EPISODE, “EGGTOWN.” & 3.” Jack’s distressed beige Jack’s black leather jack- linen shirt and brown pants et, gray check-pattern worn in the episode, “There’s long-sleeve shirt and blue No Place Like Home, Parts 2 jeans worn in the episode, & 3.” Seen on the raft when “Eggtown.” $200 – $300 the Oceanic Six are rescued. $200 – $300 573. JACK’S SUIT FROM THE EPISODE, “THERE’S NO PLACE 575. JACK’S SEASON FOUR LIKE HOME, PART 1.” Jack’s COSTUME. Jack’s gray pants, black suit (jacket and pants), striped blue button down shirt white dress shirt and black and gray sport jacket worn in tie from the episode, “There’s Season Four. $200 – $300 No Place Like Home, Part 1.” $200 – $300 157 www.liveauctioneers.com LOST | The Auction 578. KATE’S COSTUME FROM THE EPISODE, “THERE’S NO PLACE LIKE HOME, PART 1.” Kate’s jeans and green but- ton down shirt worn at the press conference in the episode, “There’s No Place Like Home, Part 1.” $200 – $300 576. JACK’S SEASON FOUR DOCTOR’S COSTUME. Jack’s white lab coat embroidered “J. Shephard M.D.,” Yves St. Laurent suit (jacket and pants), white striped shirt, gray tie, black shoes and belt. Includes medical stetho- scope and pair of knee reflex hammers used by Jack Shephard throughout the series. -

Doctor Who “ Season 2, Episode12-13, “Army of Ghosts” “Doomsday” DOCTOR: You, You've Heard of Me, Then? (你們聽說

Doctor Who “ Season 2, Episode12-13, “Army of Ghosts” “Doomsday” DOCTOR: You, you've heard of me, then? (你們聽說過我?) YVONNE: Well of course we have. And I have to say, if it wasn't for you, none of us would be here. The Doctor and the Tardis. (那當然了。我得說,要不是因為你,我們根本不會在這裡。博 士和 TARDIS!!) DOCTOR: And you are? (那你是?) YVONNE: Oh, plenty of time for that. But according to the records, you're not one for travelling alone. The Doctor and his companion. That's a pattern, isn't it, right? There's no point hiding anything. Not from us. So where is she? (那可以慢慢說。不過按紀錄,你不是單獨旅行的。博 士,和他的夥伴。就這模式,對吧? 你不用隱藏什麼,至少對我們不用。那,她在哪?) DOCTOR: Yes. Sorry. Good point. She's just a bit shy, that's all. (對,有道理。抱歉。她就是有 點害羞啦。) DOCTOR: But here she is, Rose Tyler. (就是她,Rose Tyler.) DOCTOR: Hmm. She's not the best I've ever had. Bit too blonde. Not too steady on her pins. A lot of that. (她不是我最好的夥伴。有點太金髮,做事不仔細,常這樣。) DOCTOR: And just last week, she stared into the heart of the Time Vortex and aged fifty seven years. But she'll do. (就上個禮拜,她直視時間流,結果老了 57 歲。不過還好啦。) JACKIE: I'm forty! (我才四十歲!) DOCTOR: Deluded. Bless. I'll have to trade her in. Do you need anyone? She's very good at tea. Well, I say very good, I mean not bad. Well, I say not bad. Anyway, lead on. Allons-y! But not too fast. Her ankle's going. (別唬我。上帝保佑。我得把她賣了。你們需要人嗎?他很會泡茶。額,我 說「很會」意思是不差。額,不差啦。反正呢,你帶路吧,出發!別走太快,她的腳不太好。) JACKIE: I'll show you where my ankle's going. -

Time Travel and Free Will in the Television Show Lost

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Directory of Open Access Journals Praxes of popular culture No. 1 - Year 9 12/2018 - LC.1 Kevin Drzakowski, University of Wisconsin-Stout, USA Paradox Lost: Time Travel and Free Will in the Television Show Lost Abstract The television series Lost uses the motif of time travel to consider the problem of human free will, following the tradition of Humean compatibilism in asserting that human beings possess free will in a deterministic universe. This paper reexamines Lost’s final mystery, the “Flash Sideways” world, presenting a revisionist view of the show’s conclusion that figures the Flash Sideways as an outcome of time travel. By considering the perspectives of observers who exist both within time and outside of it, the paper argues that the characters of Lost changed their destinies, even though the rules of time travel in Lost’s narrative assert that history cannot be changed. Keywords: Lost, time travel, Hume, free will, compatibilism My purpose in this paper is twofold. First, I intend to argue that ABC’s Lost follows a tradition of science fiction in using time travel to consider the problem of human free will, making an original contribution to the debate by invoking a narrative structure previously unseen in time travel stories. I hope to show that Lost, a television show that became increasingly invested in questions over free will and fate as the series progressed, makes a case for free will in the tradition of Humean compatibilism, asserting that human beings possess free will even in a deterministic world. -

Sociopathetic Abscess Or Yawning Chasm? the Absent Postcolonial Transition In

Sociopathetic abscess or yawning chasm? The absent postcolonial transition in Doctor Who Lindy A Orthia The Australian National University, Canberra, Australia Abstract This paper explores discourses of colonialism, cosmopolitanism and postcolonialism in the long-running television series, Doctor Who. Doctor Who has frequently explored past colonial scenarios and has depicted cosmopolitan futures as multiracial and queer- positive, constructing a teleological model of human history. Yet postcolonial transition stages between the overthrow of colonialism and the instatement of cosmopolitan polities have received little attention within the program. This apparent ‘yawning chasm’ — this inability to acknowledge the material realities of an inequitable postcolonial world shaped by exploitative trade practices, diasporic trauma and racist discrimination — is whitewashed by the representation of past, present and future humanity as unchangingly diverse; literally fixed in happy demographic variety. Harmonious cosmopolitanism is thus presented as a non-negotiable fact of human inevitability, casting instances of racist oppression as unnatural blips. Under this construction, the postcolonial transition needs no explication, because to throw off colonialism’s chains is merely to revert to a more natural state of humanness, that is, cosmopolitanism. Only a few Doctor Who stories break with this model to deal with the ‘sociopathetic abscess’ that is real life postcolonial modernity. Key Words Doctor Who, cosmopolitanism, colonialism, postcolonialism, race, teleology, science fiction This is the submitted version of a paper that has been published with minor changes in The Journal of Commonwealth Literature, 45(2): 207-225. 1 1. Introduction Zargo: In any society there is bound to be a division. The rulers and the ruled. -

The MULLET RAPPER

The MULLET RAPPER NEWS AREA INFO What’s Happening in the Everglades & 10,000 Islands TIDES ~ EVENTS FEBRUARY 9, 2019 - FEBRUARY 22, 2019 25¢ RESTAURANTS © 2019, K Bee Marketing P O Box 134, Everglades City, FL, 34139 Volume XI • Issue # 331 Everglades City Awarded Trail 2019 MSD Festival Town Designation by State Office February 19th-23rd Seafood Festival Everglades City has been chosen as one In 1968 at the age of 78, Entertainment Lineup of the State’s nine official “Trail Towns” Marjory Stoneman Douglas by the Office of Greenways and Trails became actively involved in (OGT). environmental issues when Friday, February 8th: The OGT was established by former she opposed a planned 5:30-6:15 Charlie Pace / Sloan Governor Rick Scott as a way to provide jetport along the Tamiami Wheeler statewide leadership and coordination to Trail. She established 6:30-7:15 The Lost Rodeo establish, expand and promote non- Friends of the Everglades and began motorized trails that make up the Florida 7:30-9:00 Let’s Hang On speaking on their behalf to public and Greenways and Trails System. private entities across the state. In doing 9:20- ? Tim Elliott (Nashville) The trail town project in Everglades so, she was able to focus attention on the Saturday, February 9th: City was spearheaded by Patty Huff after importance of protecting this national she attended a OGT presentation in treasure. 10:30-11:00 Opening Ceremony Titusville. The concept was presented to Join us in celebrating the amazing 11:00-12:30 Charlie Pace the Everglades City Council, who “river of grass” and the legacy of 1:00-2:00 Jordan Guess approved the effort as a way to help Marjory. -

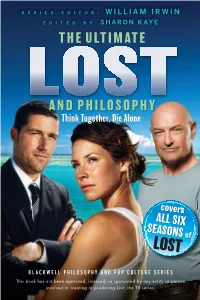

The Ultimate and Philosophy

PHILOSOPHY/POP CULTURE IRWIN SERIES EDITOR: WILLIAM IRWIN What are the metaphysics of time travel? EDITED BY SHARON KAYE How can Hurley exist in two places at the same time? THE ULTIMATE What does it mean for something to be possibly true in the fl ash-sideways universe? Does Jack have a moral obligation to his father? THE ULTIMATE What is the Tao of John Locke? Dude. So there’s, like, this island? And a bunch of us were on Oceanic fl ight 815 and we crashed on it. I kinda thought it was my fault, because of those numbers. I thought they were bad luck. We’ve seen the craziest things here, like a polar bear and a Smoke Monster, and we traveled through time back to the 1970s. And we met the Dharma dudes. Arzt even blew himself up. For a long time, I thought I was crazy. But now, I think it might have been destiny. The island’s made me question a lot of things. Like, why is it that Locke and Desmond have the same names as real philosophers? Why do so many of us have AND PHILOSOPHY trouble with our dads? Did Jack have a choice in becoming our leader? And what’s up Think Together, Die Alone with Vincent? I mean, he’s gotta be more than just a dog, right? I dunno. We’ve all felt pretty lost. I just hope we can trust Jacob, otherwise . whoa. With its sixth-season series fi nale, Lost did more than end its run as one of the most AND PHILOSOPHY talked-about TV programs of all time; it left in its wake a complex labyrinth of philosophical questions and issues to be explored. -

Accelerated Reader List

Accelerated Reader Test List Report OHS encourages teachers to implement independent reading to suit their curriculum. Accelerated Reader quizzes/books include a wide range of reading levels and subject matter. Some books may contain mature subject matter and/or strong language. If a student finds a book objectionable/uncomfortable he or she should choose another book. Test Book Reading Point Number Title Author Level Value -------------------------------------------------------------------------- 68630EN 10th Grade Joseph Weisberg 5.7 11.0 101453EN 13 Little Blue Envelopes Maureen Johnson 5.0 9.0 136675EN 13 Treasures Michelle Harrison 5.3 11.0 39863EN 145th Street: Short Stories Walter Dean Myers 5.1 6.0 135667EN 16 1/2 On the Block Babygirl Daniels 5.3 4.0 135668EN 16 Going on 21 Darrien Lee 4.8 6.0 53617EN 1621: A New Look at Thanksgiving Catherine O'Neill 7.1 1.0 86429EN 1634: The Galileo Affair Eric Flint 6.5 31.0 11101EN A 16th Century Mosque Fiona MacDonald 7.7 1.0 104010EN 1776 David G. McCulloug 9.1 20.0 80002EN 19 Varieties of Gazelle: Poems o Naomi Shihab Nye 5.8 2.0 53175EN 1900-20: A Shrinking World Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 53176EN 1920-40: Atoms to Automation Steve Parker 7.9 1.0 53177EN 1940-60: The Nuclear Age Steve Parker 7.7 1.0 53178EN 1960s: Space and Time Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 130068EN 1968 Michael T. Kaufman 9.9 7.0 53179EN 1970-90: Computers and Chips Steve Parker 7.8 0.5 36099EN The 1970s from Watergate to Disc Stephen Feinstein 8.2 1.0 36098EN The 1980s from Ronald Reagan to Stephen Feinstein 7.8 1.0 5976EN 1984 George Orwell 8.9 17.0 53180EN 1990-2000: The Electronic Age Steve Parker 8.0 1.0 72374EN 1st to Die James Patterson 4.5 12.0 30561EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Ad Jules Verne 5.2 3.0 523EN 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (Un Jules Verne 10.0 28.0 34791EN 2001: A Space Odyssey Arthur C.