The Application of Music in Industry and Its Effect Upon the Morale and Efficiency of the Worker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A ADVENTURE C COMEDY Z CRIME O DOCUMENTARY D DRAMA E

MOVIES A TO Z MARCH 2021 Ho u The 39 Steps (1935) 3/5 c Blondie of the Follies (1932) 3/2 Czechoslovakia on Parade (1938) 3/27 a ADVENTURE u 6,000 Enemies (1939) 3/5 u Blood Simple (1984) 3/19 z Bonnie and Clyde (1967) 3/30, 3/31 –––––––––––––––––––––– D ––––––––––––––––––––––– –––––––––––––––––––––– ––––––––––––––––––––––– c COMEDY A D Born to Love (1931) 3/16 m Dancing Lady (1933) 3/23 a Adventure (1945) 3/4 D Bottles (1936) 3/13 D Dancing Sweeties (1930) 3/24 z CRIME a The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn (1960) 3/23 P c The Bowery Boys Meet the Monsters (1954) 3/26 m The Daughter of Rosie O’Grady (1950) 3/17 a The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) 3/9 c Boy Meets Girl (1938) 3/4 w The Dawn Patrol (1938) 3/1 o DOCUMENTARY R The Age of Consent (1932) 3/10 h Brainstorm (1983) 3/30 P D Death’s Fireworks (1935) 3/20 D All Fall Down (1962) 3/30 c Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961) 3/18 m The Desert Song (1943) 3/3 D DRAMA D Anatomy of a Murder (1959) 3/20 e The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) 3/27 R Devotion (1946) 3/9 m Anchors Aweigh (1945) 3/9 P R Brief Encounter (1945) 3/25 D Diary of a Country Priest (1951) 3/14 e EPIC D Andy Hardy Comes Home (1958) 3/3 P Hc Bring on the Girls (1937) 3/6 e Doctor Zhivago (1965) 3/18 c Andy Hardy Gets Spring Fever (1939) 3/20 m Broadway to Hollywood (1933) 3/24 D Doom’s Brink (1935) 3/6 HORROR/SCIENCE-FICTION R The Angel Wore Red (1960) 3/21 z Brute Force (1947) 3/5 D Downstairs (1932) 3/6 D Anna Christie (1930) 3/29 z Bugsy Malone (1976) 3/23 P u The Dragon Murder Case (1934) 3/13 m MUSICAL c April In Paris -

March 2018 New Releases

March 2018 New Releases what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately! 59 Vinyl Audio 3 CD Audio 8 RICHIE KOTZEN - TONY MACALPINE - RANDY BRECKER QUINTET - FEATURED RELEASES TELECASTERS & DEATH OF ROSES LIVEAT SWEET BASIL 1988 STRATOCASTERS: Music Video KLASSIC KOTZEN DVD & Blu-ray 35 Non-Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 39 Order Form 65 Deletions and Price Changes 63 800.888.0486 THE SOULTANGLER KILLER KLOWNS FROM BRUCE’S DEADLY OUTER SPACE FINGERS 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 [BLU-RAY + DVD] DWARVES & THE SLOTHS - DUNCAN REID & THE BIG HEADS - FREEDOM HAWK - www.MVDb2b.com DWARVES MEET THE SLOTHS C’MON JOSEPHINE BEAST REMAINS SPLIT 7 INCH March Into Madness! MVD offers up a crazy batch of March releases, beginning with KILLER KLOWNS FROM OUTER SPACE! An alien invasion with a circus tent for a spaceship and Killer Klowns for inhabitants! These homicidal clowns are no laughing matter! Arrow Video’s exclusive deluxe treatment comes with loads of extras and a 4K restoration that will provide enough eye and ear candy to drive you insane! The derangement continues with HELL’S KITTY, starring a possessed cat who cramps the style of its owner, who is beginning a romantic relationship. Call a cat exorcist, because this fiery feline will do anything from letting its master get some pu---! THE BUTCHERING finds a serial killer returning to a small town for unfinished business. What a cut-up! The King of Creepy, CHRISTOPHER LEE, stars in the 1960 film CITY OF THE DEAD, given new life with the remastered treatment. -

Download Chapter (PDF)

PLATES 1. Cole Porter, Yale yearbook photograph (1913). 2. Westleigh Farms, Cole Porter’s childhood home in Indiana (2011). 3. Cole Porter’s World War I draft registration card (5 June 1917). War Department, Office of the Provost Marshal General. 4. Linda Porter, passport photograph (1919). 5. Cole Porter, Linda Porter, Bernard Berenson and Howard Sturges in Venice (c.1923). 6. Gerald Murphy, Ginny Carpenter, Cole Porter and Sara Murphy in Venice (1923). 7. Serge Diaghilev, Boris Kochno, Bronislava Nijinska, Ernest Ansermet and Igor Stravinsky in Monte Carlo (1923). Library of Congress, Music Division, Reproduction number: 200181841. 8. Letter from Cole Porter to Boris Kochno (September 1925). Courtesy of The Cole Porter Musical and Literary Property Trusts. 9. Scene from the original stage production of Fifty Million Frenchmen (1929). PHOTOFEST. 10. Irene Bordoni, star of Porter’s show Paris (1928). 11. Sheet music, ‘Love for Sale’ from The New Yorkers (1930). 12. Production designer Jo Mielziner showing a set for Jubilee (1935). PHOTOFEST. 13. Cole Porter composing as he reclines on a couch in the Ritz Hotel during out-of-town tryouts for Du Barry Was a Lady (1939). George Karger / Getty Images. 14. Cole and Linda Porter (c.1938). PHOTOFEST. 15. Ethel Merman in the New York production of Cole Porter’s Panama Hattie (1940). George Karger / Getty Images. vi PLATES 16. Sheet music, ‘Let’s Be Buddies’ from Panama Hattie (1940). 17. Draft of ‘I Am Ashamed that Women Are So Simple’ from Kiss Me, Kate (1948), Library of Congress. Courtesy of The Cole Porter Musical and Literary Property Trusts. -

Cole Albert Porter (June 9, 1891 October 15, 1964) Was An

Cole Albert Porter (June 9, 1891 October 15, 1964) was an American composer and songwriter. Born to a wealthy family in Indiana, he defied the wishes of his dom ineering grandfather and took up music as a profession. Classically trained, he was drawn towards musical theatre. After a slow start, he began to achieve succe ss in the 1920s, and by the 1930s he was one of the major songwriters for the Br oadway musical stage. Unlike many successful Broadway composers, Porter wrote th e lyrics as well as the music for his songs. After a serious horseback riding accident in 1937, Porter was left disabled and in constant pain, but he continued to work. His shows of the early 1940s did not contain the lasting hits of his best work of the 1920s and 30s, but in 1948 he made a triumphant comeback with his most successful musical, Kiss Me, Kate. It w on the first Tony Award for Best Musical. Porter's other musicals include Fifty Million Frenchmen, DuBarry Was a Lady, Any thing Goes, Can-Can and Silk Stockings. His numerous hit songs include "Night an d Day","Begin the Beguine", "I Get a Kick Out of You", "Well, Did You Evah!", "I 've Got You Under My Skin", "My Heart Belongs to Daddy" and "You're the Top". He also composed scores for films from the 1930s to the 1950s, including Born to D ance (1936), which featured the song "You'd Be So Easy to Love", Rosalie (1937), which featured "In the Still of the Night"; High Society (1956), which included "True Love"; and Les Girls (1957). -

Cole Porter Lesson Plan

COLE PORTER Gay U.S. Composer (1893-1964) Cole Porter remains one of America's all-time greatest composers and songwriters – one of the few who wrote both the lyrics and the music. His hits include the musical comedies The Gay Divorce (1932), Anything Goes (1934), Panama Hattie (1939), Kiss Me, Kate (1948) and Can-Can (1952); and featured songs like "Night and Day", "I Get a Kick out of You", "I've Got You Under My Skin" and “Begin the Beguine.” He worked with legendary stars Fred Astaire, Ethel Merman, Fanny Brice, Judy Garland, Gene Kelly, Roy Rogers, Bing Crosby, Mary Martin and the Andrews Sisters; and is considered one of the principal contributors to The Great American Songbook. He married his close friend, socialite Linda Lee Thomas, in 1919 – a union that assured her social status while increasing his chances for success in his career. They lived a happy, publicly acceptable life, but Porter’s reputation as a regular fixture at some of underground Hollywood’s most notorious gay gatherings led to hushed rumors within upper-crust circles that threatened Thomas’s social standing. They separated in the early 1930s (but did not divorce) and remained close friends. In 1937 Porter was crippled when his legs were crushed in a riding accident. He was in the hospital for months, struggling against mental and physical decline, though he continued to write with some success for the next several years. But the death of his beloved mother in 1952, followed by his wife’s passing in 1954, and the amputation of his right leg in 1958, took its toll. -

Addison Richards Ç”Μå½± ĸ²È¡Œ (Ť§Å…¨)

Addison Richards 电影 串行 (大全) Reprisal! https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/reprisal%21-3930254/actors Let's Be Ritzy https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/let%27s-be-ritzy-22079442/actors Inside Information https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/inside-information-18465537/actors Always a Bridesmaid https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/always-a-bridesmaid-23020746/actors Blue, White and Perfect https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/blue%2C-white-and-perfect-20649374/actors Little Big Shot https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/little-big-shot-6649096/actors Draegerman Courage https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/draegerman-courage-10576589/actors Where Are Your Children? https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/where-are-your-children%3F-3567712/actors A Close Call for Ellery https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-close-call-for-ellery-queen-84366182/actors Queen Gateway https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/gateway-11612443/actors The Girl from Missouri https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-girl-from-missouri-1753876/actors Accidents Will Happen https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/accidents-will-happen-16038863/actors Whispering Enemies https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/whispering-enemies-4019495/actors The Gambler Wore a Gun https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/the-gambler-wore-a-gun-15599546/actors A-Haunting We Will Go https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/a-haunting-we-will-go-3005526/actors Design for Scandal https://zh.listvote.com/lists/film/movies/design-for-scandal-5264339/actors -

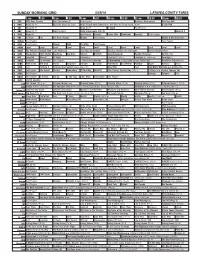

Sunday Morning Grid 5/29/16 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/29/16 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) Paid Program Nicklaus’ Masterpiece PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) (TVG) 2016 French Open Tennis Men’s and Women’s Fourth Round. (N) Å Senior PGA 5 CW News (N) Å News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å Indy Pre-Race 2016 Indianapolis 500 (N) World of X 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Pastor Mike Woodlands Amazing Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program Marley & Me ››› (PG) 13 MyNet Paid Program Paid Program 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Dr. Willar Paid Program 22 KWHY Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local Local 24 KVCR The Patient’s Playbook With Leslie Michelson Easy Yoga for Arthritis Timeless Tractors: The Collectors Forever Wisdom-Dyer 28 KCET Wunderkind 1001 Nights Bug Bites Bug Bites Edisons Biz Kid$ Aging Backwards Healthy Hormones Eat Fat, Get 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Leverage Å Leverage (TV14) Å Leverage The Inside Job. Leverage Å 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Paid Program La Rosa de Guadalupe El Barrendero (1982) Mario Moreno, María Sorté. República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Schuller In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Formula One Racing Monaco Grand Prix. -

Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection

Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection Recordings are on vinyl unless marked otherwise marked (* = Cassette or # = Compact Disc) KEY OC - Original Cast TV - Television Soundtrack OBC - Original Broadway Cast ST - Film Soundtrack OLC - Original London Cast SC - Studio Cast RC - Revival Cast ## 2 (OC) 3 GUYS NAKED FROM THE WAIST DOWN (OC) 4 TO THE BAR 13 DAUGHTERS 20'S AND ALL THAT JAZZ, THE 40 YEARS ON (OC) 42ND STREET (OC) 70, GIRLS, 70 (OC) 81 PROOF 110 IN THE SHADE (OC) 1776 (OC) A A5678 - A MUSICAL FABLE ABSENT-MINDED DRAGON, THE ACE OF CLUBS (SEE NOEL COWARD) ACROSS AMERICA ACT, THE (OC) ADVENTURES OF BARON MUNCHHAUSEN, THE ADVENTURES OF COLORED MAN ADVENTURES OF MARCO POLO (TV) AFTER THE BALL (OLC) AIDA AIN'T MISBEHAVIN' (OC) AIN'T SUPPOSED TO DIE A NATURAL DEATH ALADD/THE DRAGON (BAG-A-TALE) Bruce Walker Musical Theater Recording Collection ALADDIN (OLC) ALADDIN (OC Wilson) ALI BABBA & THE FORTY THIEVES ALICE IN WONDERLAND (JANE POWELL) ALICE IN WONDERLAND (ANN STEPHENS) ALIVE AND WELL (EARL ROBINSON) ALLADIN AND HIS WONDERFUL LAMP ALL ABOUT LIFE ALL AMERICAN (OC) ALL FACES WEST (10") THE ALL NIGHT STRUT! ALICE THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS (TV) ALL IN LOVE (OC) ALLEGRO (0C) THE AMAZING SPIDER-MAN AMBASSADOR AMERICAN HEROES AN AMERICAN POEM AMERICANS OR LAST TANGO IN HUAHUATENANGO .....................(SF MIME TROUPE) (See FACTWINO) AMY THE ANASTASIA AFFAIRE (CD) AND SO TO BED (SEE VIVIAN ELLIS) AND THE WORLD GOES 'ROUND (CD) AND THEN WE WROTE... (FLANDERS & SWANN) AMERICAN -

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection a Handlist

The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection A Handlist A wide-ranging collection of c. 4000 individual popular songs, dating from the 1920s to the 1970s and including songs from films and musicals. Originally the personal collection of the singer Rita Williams, with later additions, it includes songs in various European languages and some in Afrikaans. Rita Williams sang with the Billy Cotton Club, among other groups, and made numerous recordings in the 1940s and 1950s. The songs are arranged alphabetically by title. The Rita Williams Popular Song Collection is a closed access collection. Please ask at the enquiry desk if you would like to use it. Please note that all items are reference only and in most cases it is necessary to obtain permission from the relevant copyright holder before they can be photocopied. Box Title Artist/ Singer/ Popularized by... Lyricist Composer/ Artist Language Publisher Date No. of copies Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Dans met my Various Afrikaans Carstens- De Waal 1954-57 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Careless Love Hart Van Steen Afrikaans Dee Jay 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Ruiter In Die Nag Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1963 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Van Geluk Tot Verdriet Gideon Alberts/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs Wye, Wye Vlaktes Martin Vorster/ Anton De Waal Afrikaans Impala 1970 1 Afrikaans, Czech, French, Italian, Swedish Songs My Skemer Rapsodie Duffy -

Copyrighted Material

335 Index a “After You Get What You Want, You “Aba Daba Honeymoon” 151 Don’t Want It” 167 ABBA 313 Against All Odds (1984) 300 Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein “Age of Not Believing, The” 257 (1948) 155 Aguilera, Christina 323, 326 Abbott, Bud 98–101, 105, 109, 115 “Ah Still Suits Me” 87 ABC 229–230 “Ah, Sweet Mystery of Life” 78 Abdul, Paula 291 AIDS 317–318 About Face (1953) 151 “Ain’t There Anyone Here for “Abraham” 110–111 Love?” 170 Absolute Beginners (1986) 299 Aladdin (1958) 181 Academy Awards 46, 59, 73–74, 78, 82, Aladdin (1992) 309–310, 312, 318, 330 89, 101, 103, 107, 126, 128, 136, 140, Aladdin II, The Return of Jafar 142, 148–149, 151, 159, 166, 170, 189, (1994) 309 194, 200, 230, 232–233, 238, 242, 263, Alamo, The (1960) 187 267, 271, 282, 284, 286, 299, 308–309, Alexander’s Ragtime Band (1938) 83, 319, 320–321 85–88 Ackroyd, Dan 289 Alice in Wonderland (1951) 148 Adler, Richard 148 Alice in Wonderland: An X‐Rated Admiral Broadway Revue (1949) 180 Musical Fantasy (1976) 269 Adorable (1933) 69 All‐Colored Vaudeville Show, An Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the (1935) 88 Desert, The (1994) 319 “All God’s Chillun Got Rhythm” 88–89 African AmericansCOPYRIGHTED 13–17, 21, 24, 28, 40, All New MATERIAL Mickey Mouse Club, The 43, 54–55, 78, 87–89, 109–111, 132, (1989–94) 326 163–164, 193–194, 202–203, 205–209, “All Out for Freedom” 102 213–216, 219, 226, 229, 235, 237, All‐Star Revue (1951–53) 179 242–243, 258, 261, 284, 286–287, 289, All That Jazz (1979) 271–272, 292, 309, 293–295, 314–315, 317–319 320, 322 “After the Ball” 22 “All You Need Is Love” 244 Free and Easy? A Defining History of the American Film Musical Genre, First Edition. -

Richie Kotzen Wave of Emotion Mp3, Flac, Wma

Richie Kotzen Wave Of Emotion mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Funk / Soul Album: Wave Of Emotion Country: US Released: 2000 Style: Hard Rock MP3 version RAR size: 1786 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1220 mb WMA version RAR size: 1830 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 698 Other Formats: APE FLAC TTA MIDI MPC DTS MP3 Tracklist Hide Credits Wave Of Emotion 1 3:07 Written-By – Deanna Eve, Richie Kotzen Times Gonna Tell 2 4:44 Written-By – Richie Kotzen, Robert Hazzard* No Reason 3 5:04 Written-By – Richie Kotzen Breakdown 4 2:55 Written-By – Richie Kotzen I'm Comin' Out 5 2:50 Written-By – Richie Kotzen Moonshine 6 3:46 Written-By – Richie Kotzen Stoned 7 3:46 Written-By – Glenn Hughes, Richie Kotzen Sovereign 8 3:20 Written-By – Richie Kotzen World Affair 9 3:18 Written-By – Richie Kotzen Degeneration 10 4:39 Written-By – Richie Kotzen Air 11 4:34 Written-By – Richie Kotzen Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – Eagle Rock Entertainment PLC Copyright (c) – Eagle Rock Entertainment PLC Licensed To – Spitfire Records Inc. Recorded At – Trist A' Whirl Mixed At – Trist A' Whirl Published By – Richie Kotzen Music Published By – Wb Music Corp. Credits Backing Vocals [Additional] – Deanna Eve (tracks: 1), Glenn Hughes (tracks: 7) Bass – Melvin Brandon Jr. (tracks: 2) Co-producer – Atma Anur (tracks: 6, 8) Coordinator – Micah "lucky g" Smith Design, [Additional] – Chuck Wright Drums – Richie Kotzen (tracks: 3) Drums, Percussion – Atma Anur Lead Vocals, Backing Vocals, Guitar, Piano, Organ, Clavinet, Synthesizer, Mandolin, Bass – Richie Kotzen Management – Larry Mazer Photography, Art Direction – William Hames Producer – Richie Kotzen Recorded By, Mixed By – Dexter Smittle, Lole Diro Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Text): 6 70211 50602 0 Matrix / Runout: [WEA Mfg. -

Kiss Me, Kate Music and Lyrics by Cole Porter Book by Sam & Bella Spewack

Kiss Me, Kate Music and lyrics by Cole Porter Book by Sam & Bella Spewack Teaching resources researched and written by Simon Pollard 1 Kiss Me, Kate – teaching ResouRces Kiss Me, Kate Contents Kiss Me, Kate at The Old Vic 3 Cole Porter: His Story 4 Sam and Bella Spewack: Their Story 5 Cole Porter Chronology 6 Kiss Me, Kate: Notable Productions 7 Another Op’nin, Another Show: The Story Behind Kiss Me, Kate 8 Kiss Me, Kate Synopsis 9 Character Breakdown 10 Musical Numbers 11 The Taming of the Shrew Synopsis 13 I Hate Men: Gender politics in Kiss Me, Kate & The Taming of the Shrew 14 ‘Breaking the color line’: Integrating the theatre in 1940s America 15 If Music Be the Food of Love: Musicals Based on Shakespeare Plays 16 In conversation with... Hannah Waddingham 17 Adam Garcia 18 Clive Rowe 19 Gareth Valentine, Musical Director 20 Bibliography 21 2 3 Kiss Me, Kate – teaching ResouRces Cole Porter His Story Cole Albert Porter was born on 9 June 1891 in Peru, Indiana. His father, Sam Porter, was a local pharmacist and his mother, Kate Cole, was the daughter of James Omar ‘J. O.’ Cole allegedly ‘the richest man in Indiana’. Porter proved a talented musician from an early age, learning the violin and piano from the age of six, and he composed his first operetta with the help of his mother when he was just ten years old. In 1905, he enrolled at the Worcester Academy in Massachusetts, where his musical skills made him very popular and he was elected class valedictorian.