About the Appearance of the Russian Border in Lapland (Some Results of the Discussion) © Pavel V

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Murmansk, Russia Yu.A.Shustov

the Exploration,of SALMON RIVERS OF THE KOLA PENINSULA. REPRODUCTIVE POTENTIAL AND STOCK STATUS OF THE ATLANTIC SALMON , FROM THE KOLA RIVER by A.V.Zubchenko The Knipovich'Polar Research Institute ofMarine Fisheries and • Oceanography (PINRO), Murmansk, Russia Yu.A.Shustov Biological Institute of the Scientific Center of the Russian Academy of Science, Petrozavodsk, Russia A.E.Bakulina Murmansk Regional Directorate of Fish Conservation and Enhancement, Murmansk, Russia INTRODUCTION The paper presented keeps the series of papers on reproductive • potential and stock status of salmon from the rivers of the Kola 'Peninsula (Zubchenko, Kuzmin, 1993; Zubchenko, 1994). Salmon rivers of this area have been affected by significant fishing pressure for a long time, and, undoubtedly, these data are of great importance for assessment of optimum abundance of spawners, necessary for spawning grounds, for estimating the exploitation rate of the stock, the optimum abundance of released farmed juveniles and for other calculations. At the same time, despite the numerous papers, the problem of the stock status of salmon from the Kola River was discussed'long aga (Azbelev, 1960), but there are no data on the reproductive potential of this river in literature. ' The Kola River is one of the most important fishing rivers of Russia. It flows out of the Kolozero Lake, situated almost in the central part of the Kola Peninsula,and falls into the Kola Bay of the Barents Sea. Locating in the hollow of the transversal break, along the line of the Imandra Lake-the Kola Bay, its basin borders on the water removing of the Imandra Lake in the south, .. -

A Handbook of Siberia and Arctic Russia : Volume 1 : General

Presented to the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO LIBRARY by the ONTARIO LEGISLATIVE LIBRARY 1980 I. D. 1207 »k.<i. 57182 g A HANDBOOK OF**' SIBERIA AND ARCTIC RUSSIA Volume I GENERAL 57182 Compiled by the Geographical Section of the Naval Intelligence Division, Naval Staff, Admiralty LONDON : PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE. To be purchased through any Bookseller or directly from H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses : Imperial House, Kingswav, London, W.C. 2, and 28 1 Abingdon Street, London, S. W. ; 37 Peter Street, Manchester ; 1 St. Andrew's Crescent, Cardiff ; 23 Forth Street, Edinburgh ; or from E. PONSONBY, Ltd., 116 Grafton Street, Dublin. Price 7s. 6d. net Printed under the authority of His Majesty's Stationery Office By Frederick Hall at the University Press, Oxford. NOTE The region covered in this Handbook includes besides Liberia proper, that part of European Russia, excluding Finland, which drains to the Arctic Ocean, and the northern part of the Central Asian steppes. The administrative boundaries of Siberia against European Russia and the Steppe provinces have been ignored, except in certain statistical matter, because they follow arbitrary lines through some of the most densely populated parts of Asiatic Russia. The present volume deals with general matters. The two succeeding volumes deal in detail respectively with western Siberia, including Arctic Russia, and eastern Siberia. Recent information about Siberia, even before the outbreak of war, was difficult to obtain. Of the remoter parts little is known. The volumes are as complete as possible up to 1914 and a few changes since that date have been noted. -

Migratory Fish Stock Management in Trans-Boundary Rivers

Title Migratory fish stock management in trans-boundary rivers Author(s) Erkinaro, Jaakko フィンランド-日本 共同シンポジウムシリーズ : 北方圏の環境研究に関するシンポジウム2012(Joint Finnish- Citation Japanese Symposium Series Northern Environmental Research Symposium 2012). 2012年9月10日-14日. オウル大学 、オウランカ研究所, フィンランド. Issue Date 2012-09-10 Doc URL http://hdl.handle.net/2115/51370 Type conference presentation File Information 07_JaakkoErkinaro.pdf Instructions for use Hokkaido University Collection of Scholarly and Academic Papers : HUSCAP Migratory fish stock management in trans-boundary rivers Jaakko Erkinaro Finnish Game and Fisheries Research Institute, Oulu Barents Sea Atlantic ocean White Sea Baltic Sea Finland shares border river systems with Russia, Norway and Sweden that discharge to the Baltic Sea or into the Atlantic Ocean via White Sea or Barents Sea Major trans-boundary rivers between northern Finland and neighbouring countries Fin-Swe: River Tornionjoki/ Torneälven Fin-Nor: River Teno / Tana Fin-Rus: River Tuuloma /Tuloma International salmon stock management • Management of fisheries in international waters: International fisheries commissions, European Union • Bilateral management of trans-boundary rivers: Bilateral agreements between governments • Regional bilateral management Bilateral agreements between regional authorities Advice from corresponding scientific bodies International and bilateral advisory groups International Council for the Exploration of the Sea - Advisory committee for fisheries management - Working groups: WG for Baltic salmon and sea trout -

Moscow Defense Brief Your Professional Guide Inside # 2, 2011

Moscow Defense Brief Your Professional Guide Inside # 2, 2011 Troubled Waters CONTENTS Defense Industries #2 (24), 2011 Medium-term Prospects for MiG Corporation PUBLISHER After Interim MMRCA Competition Results 2 Centre for Russian Helicopter Industry: Up and Away 4 Analysis of Strategies and Technologies Arms Trade CAST Director & Publisher Exports of Russian Fighter Jets in 1999-2010 8 Ruslan Pukhov Editor-in-Chief Mikhail Barabanov International Relations Advisory Editors Georgian Lesson for Libya 13 Konstantin Makienko Alexey Pokolyavin Researchers Global Security Ruslan Aliev Polina Temerina Missile Defense: Old Problem, No New Solution 15 Dmitry Vasiliev Editorial Office Armed Forces 3 Tverskaya-Yamskaya, 24, office 5, Moscow, Russia 125047 Reform of the Russian Navy in 2008-2011 18 phone: +7 499 251 9069 fax: +7 495 775 0418 http://www.mdb.cast.ru/ Facts & Figures To subscribe, contact Incidents Involving Russian Submarines in 1992-2010 23 phone: +7 499 251 9069 or e-mail: [email protected] 28 Moscow Defense Brief is published by the Centre for Analysis of Strategies Our Authors and Technologies All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical or photocopying, recording or otherwise, without reference to Moscow Defense Brief. Please note that, while the Publisher has taken all reasonable care in the compilation of this publication, the Publisher cannot accept responsibility for any errors or omissions in this publication or for any loss arising therefrom. Authors’ opinions do not necessary reflect those of the Publisher or Editor Translated by: Ivan Khokhotva Computer design & pre-press: B2B design bureau Zebra www.zebra-group.ru Cover Photo: K-433 Svyatoy Georgiy Pobedonosets (Project 667BDR) nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine at the Russian Pacific Fleet base in Vilyuchinsk, February 25, 2011. -

DRAINAGE BASINS of the WHITE SEA, BARENTS SEA and KARA SEA Chapter 1

38 DRAINAGE BASINS OF THE WHITE SEA, BARENTS SEA AND KARA SEA Chapter 1 WHITE SEA, BARENTS SEA AND KARA SEA 39 41 OULANKA RIVER BASIN 42 TULOMA RIVER BASIN 44 JAKOBSELV RIVER BASIN 44 PAATSJOKI RIVER BASIN 45 LAKE INARI 47 NÄATAMÖ RIVER BASIN 47 TENO RIVER BASIN 49 YENISEY RIVER BASIN 51 OB RIVER BASIN Chapter 1 40 WHITE SEA, BARENT SEA AND KARA SEA This chapter deals with major transboundary rivers discharging into the White Sea, the Barents Sea and the Kara Sea and their major transboundary tributaries. It also includes lakes located within the basins of these seas. TRANSBOUNDARY WATERS IN THE BASINS OF THE BARENTS SEA, THE WHITE SEA AND THE KARA SEA Basin/sub-basin(s) Total area (km2) Recipient Riparian countries Lakes in the basin Oulanka …1 White Sea FI, RU … Kola Fjord > Tuloma 21,140 FI, RU … Barents Sea Jacobselv 400 Barents Sea NO, RU … Paatsjoki 18,403 Barents Sea FI, NO, RU Lake Inari Näätämö 2,962 Barents Sea FI, NO, RU … Teno 16,386 Barents Sea FI, NO … Yenisey 2,580,000 Kara Sea MN, RU … Lake Baikal > - Selenga 447,000 Angara > Yenisey > MN, RU Kara Sea Ob 2,972,493 Kara Sea CN, KZ, MN, RU - Irtysh 1,643,000 Ob CN, KZ, MN, RU - Tobol 426,000 Irtysh KZ, RU - Ishim 176,000 Irtysh KZ, RU 1 5,566 km2 to Lake Paanajärvi and 18,800 km2 to the White Sea. Chapter 1 WHITE SEA, BARENTS SEA AND KARA SEA 41 OULANKA RIVER BASIN1 Finland (upstream country) and the Russian Federation (downstream country) share the basin of the Oulanka River. -

Kola Oleneostrovskiy Grave Field: a Unique Burial Site in the European Arctic

Kola Oleneostrovskiy Grave Field: A Unique Burial Site in the European Arctic Anton I. Murashkin, Evgeniy M. Kolpakov, Vladimir Ya. Shumkin, Valeriy I. Khartanovich & Vyacheslav G. Moiseyev Anton I. Murashkin, Department of Archaeology, St Petersburg State University, Mendeleyevskaya liniya 5, RU-199034 St Petersburg, Russia: [email protected], [email protected] Evgeniy M. Kolpakov, Department of Palaeolithic, Institute for the History of Material Culture, Russian Academy of Sciences, Dvortsovaya nab. 18, RU-191186 St Petersburg, Russia: [email protected] Vladimir ya. Shumkin, Department of Palaeolithic, Institute for the History of Material Culture, Russian Academy of Sciences, Dvortsovaya nab. 18, RU-191186 St Petersburg, Russia: [email protected] Valeriy I. Khartanovich, Department of Anthropology, Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera), Russian Academy of Sciences, Universitetskaya nab. 3, RU-199034 St Petersburg, Russia: [email protected] Vyacheslav G. Moiseyev, Department of Anthropology, Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera), Russian Academy of Sciences, Universitetskaya nab. 3, RU-199034 St Petersburg, Russia: [email protected] Abstract The Kola Oleneostrovskiy grave field (KOG) is the main source of information for the physical and cultural anthropology of the Early Metal Period population of the Kola Peninsula and the whole northern Fennoscandia.1 Excavations were conducted here in 1925, 1928, 1947–1948, and 2001–2004 by A. Shmidt, N. Gurina, and V. Shumkin. Altogether 32 burials containing the remains of 43 individuals were investigated. During the excavations, also remains of wooden grave constructions were found. The site is exceptionally rich in burial goods, including numerous bone, antler, stone, ceramic, and bronze items. -

Nuclear Reactors in Arctic Russia

NUCLEAR REACTORS IN ARCTIC RUSSIA Scenario 2035 The nuclearification of Russian Arctic territories is by Moscow given highest priority for development in shipping, infrastructure and exploration of natural resources. Additionally, the number of navy military reactors in the north will increase substantially over the next 15 years. This scenario paper gives an overview of the situation. The paper is part of the Barents Observer’s analytical popular science studies on developments in the Euro-Arctic Region. Thomas Nilsen June 2019 June 2019 The Barents Observer – Nuclear Reactors in Northern Russia, June 2019 1 June 2019 Published by: The Independent Barents Observer Address: Storgata 5, 9900 Kirkenes, Norway E-mail: [email protected] thebarentsobserver.com (English, Russian and Chinese versions of the news-portal) Twitter @BarentsNews Instagram: @BarentsObserver Facebook.com/BarentsObserver/ Author: Thomas Nilsen, E-mail: [email protected] Twitter: @NilsenThomas Photos and illustrations: Rosatom, Rosatomflot, Thomas Nilsen, Oleg Kuleshov, H I Sutton, Atle Staalesen, Alexey Mkrtchyan, Wikimedia Commons. Keywords: Nuclear, Reactors, Icebreakers, Submarines, Northern Fleet, Russia, Arctic, Northern Sea Route, Nuclear Power, Kola Peninsula, Siberia, Arkhangelsk, Severodvinsk, Severomorsk, Murmansk, Pevek, Barents Sea, Kara Sea, White Sea. This publication is financially supported with a grant from the Norwegian Government’s Nuclear Action Plan administrated by the Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority. (www.dsa.no/en/). The Barents Observer – Nuclear Reactors in Northern Russia, June 2019 2 June 2019 Introduction At the peak of the Cold War some 150 nuclear-powered submarines were based on the Barents Sea coast of the Kola Peninsula. Many ships were transporting and storing nuclear waste and at shipyards and bases, spent nuclear fuel and radioactive waste was accumulated. -

Riessler/Wilbur: Documenting the Endangered Kola Saami Languages

BERLINER BEITRÄGE ZUR SKANDINAVISTIK Titel/ Språk og språkforhold i Sápmi title: Autor(in)/ Michael Riessler/Joshua Wilbur author: Kapitel/ »Documenting the endangered Kola Saami languages« chapter: In: Bull, Tove/Kusmenko, Jurij/Rießler, Michael (Hg.): Språk og språkforhold i Sápmi. Berlin: Nordeuropa-Institut, 2007 ISBN: 973-3-932406-26-3 Reihe/ Berliner Beiträge zur Skandinavistik, Bd. 11 series: ISSN: 0933-4009 Seiten/ 39–82 pages: Diesen Band gibt es weiterhin zu kaufen. This book can still be purchased. © Copyright: Nordeuropa-Institut Berlin und Autoren. © Copyright: Department for Northern European Studies Berlin and authors. M R J W Documenting the endangered Kola Saami languages . Introduction The present paper addresses some practical and a few theoretical issues connected with the linguistic field research being undertaken as part of the Kola Saami Documentation Project (KSDP). The aims of the paper are as follows: a) to provide general informa- tion about the Kola Saami languages und the current state of their doc- umentation; b) to provide general information about KSDP, expected project results and the project work flow; c) to present certain soft- ware tools used in our documentation work (Transcriber, Toolbox, Elan) and to discuss other relevant methodological and technical issues; d) to present a preliminary phoneme analysis of Kildin and other Kola Saami languages which serves as a basis for the transcription convention used for the annotation of recorded texts. .. The Kola Saami languages The Kola Saami Documentation Project aims at documenting the four Saami languages spoken in Russia: Skolt, Akkala, Kildin, and Ter. Ge- nealogically, these four languages belong to two subgroups of the East Saami branch: Akkala and Skolt belong to the Mainland group (together with Inari, which is spoken in Finland), whereas Kildin and Ter form the Peninsula group of East Saami. -

Russian Federation - Support to the National Programme of Action for the Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment”

UNEP/GEF Project “Russian Federation - Support to the National Programme of Action for the Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment” 5th Steering Committee Meeting 24-25 March 2011 UN Building, 9 Leontyevskiy Lane, Moscow Report On the Fifth Meeting of the Project Steering Committee ______________________________________________ Prepared by: the Project Office Status: approved 1 Table of Annexes Annex I List of Participants Annex II Revised Agenda of the Meeting Annex III Summary of the Project Implementation versus the bench marks stipulated in the original Project Document and supplemented by the Project Steering Committee Annex IV Main results of pre-investment studies in the Russian Arctic Annex V Report on Environmental protection System Component Implementation Annex VI Main results of demo and pilot projects implemented on the NPA-Arctic Project life time 2 Report On the Fifth Meeting of the Project Steering Committee Introduction The 5th meeting of the Steering Committee (StC) for the UNEP/GEF Project “Russian Federation - Support to the National Programme of Action for the Protection of the Arctic Marine Environment” was convened on 24-25 March 2011 in the UN Building in Moscow, Russian Federation. The meeting was chaired by Mr. Boris Morgunov, the Assistant to the Minister of Economic Development of the Russian Federation and the representative of the Project Executing Agency. The meeting started at 10.00 on March 24, 2011. The list of participants is presented in Annex I of this report. AGENDA ITEM 1: OPENING OF THE MEETING AND ADOPTION OF THE AGENDA The Chairman welcomed participants and informed the StC members that this meeting would be the final meeting of the StC for the UNEP/GEF RF NPA-Arctic Project. -

Nuclear Reactors in Arctic Russia

NUCLEAR REACTORS IN ARCTIC RUSSIA Scenario 2035 The nuclearification of Russian Arctic territories is by Moscow given highest priority for development in shipping, infrastructure and exploration of natural resources. Additionally, the number of navy military reactors in the north will increase substantially over the next 15 years. This scenario paper gives an overview of the situation. The paper is part of the Barents Observer’s analytical popular science studies on developments in the Euro-Arctic Region. Thomas Nilsen June 2019 0 June 2019 The Barents Observer – Nuclear Reactors in Northern Russia, June 2019 1 June 2019 Published by: The Independent Barents Observer Address: Storgata 5, 9900 Kirkenes, Norway E-mail: [email protected] thebarentsobserver.com (English, Russian and Chinese versions of the news-portal) Twitter @BarentsNews Instagram: @BarentsObserver Facebook.com/BarentsObserver/ Author: Thomas Nilsen, E-mail: [email protected] Twitter: @NilsenThomas Photos and illustrations: Rosatom, Rosatomflot, Thomas Nilsen, Oleg Kuleshov, H I Sutton, Atle Staalesen, Alexey Mkrtchyan, Wikimedia Commons. Keywords: Nuclear, Reactors, Icebreakers, Submarines, Northern Fleet, Russia, Arctic, Northern Sea Route, Nuclear Power, Kola Peninsula, Siberia, Arkhangelsk, Severodvinsk, Severomorsk, Murmansk, Pevek, Barents Sea, Kara Sea, White Sea. This publication is financially supported with a grant from the Norwegian Government’s Nuclear Action Plan administrated by the Norwegian Radiation and Nuclear Safety Authority. (www.dsa.no/en/). The Barents Observer – Nuclear Reactors in Northern Russia, June 2019 2 June 2019 Introduction At the peak of the Cold War some 150 nuclear-powered submarines were based on the Barents Sea coast of the Kola Peninsula. Many ships were transporting and storing nuclear waste and at shipyards and bases, spent nuclear fuel and radioactive waste was accumulated. -

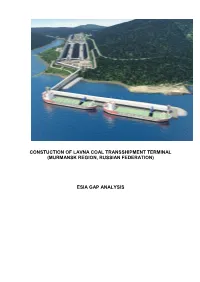

Lavna Coal Transshipment Terminal Gap-Analysis

CONSTUCTION OF LAVNA COAL TRANSSHIPMENT TERMINAL (MURMANSK REGION, RUSSIAN FEDERATION) ESIA GAP ANALYSIS CONSTUCTION OF LAVNA COAL TRANSSHIPMENT TERMINAL (MURMANSK REGION, RUSSIAN FEDERATION) ESIA GAP ANALYSIS Prepared by: Ecoline Environmental Assessment Centre (Moscow, Russia) Director: Dr. Marina V. Khotuleva ___________________________ Tel./Fax: +7 495 951 65 85 Address: 21, Build.8, Bolshaya Tatarskaya, 115184, Moscow, Russian Federation Mobile: +7 903 5792099 e-mail: [email protected] Prepared for: Black Sea Trade and Development Bank (BSTDB) © Ecoline EA Centre NPP, 2018 CONSTUCTION OF LAVNA COAL TRANSSHIPMENT TERMINAL (MURMANSK REGION, RUSSIAN FEDERATION). ESIA GAP ANALYSIS REPORT DETAILS OF DOCUMENT PREPARATION AND ISSUE Version Prepared by Reviewed Authorised for Issue Date Description by issue 0 Dr. Marina Dr. Olga Dr. Marina 23/11/2018 Version for Khotuleva Demidova Khotuleva BSTDB’s Dr. Tatiana internal review Laperdina Anna Kuznetsova 3 CONSTUCTION OF LAVNA COAL TRANSSHIPMENT TERMINAL (MURMANSK REGION, RUSSIAN FEDERATION). ESIA GAP ANALYSIS REPORT LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS BAT Best Available Techniques BREF BAT Reference Document BSTDB Black Sea Trade and Development Bank CLS Core Labour Standards CTS Conveyor transport system CTT Coal Transshipment Terminal E&S Environmental and Social EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development EEC European Economic Council EES Environmental and Engineering Studies EHS Environmental, Health and Safety EIA Environmental Impact Assessment EIB European Investment Bank EPC Engineering, -

Seabird Harvest in Iceland Aever Petersen, the Icelandic Institute of Natural History

CAFF Technical Report No. 16 September 2008 SEABIRD HARVEST IN THE ARCTIC CAFFs CIRCUMPOLAR SEABIRD GROUP Acknowledgements CAFF Designated Agencies: • Directorate for Nature Management, Trondheim, Norway • Environment Canada, Ottawa, Canada • Faroese Museum of Natural History, Tórshavn, Faroe Islands (Kingdom of Denmark) • Finnish Ministry of the Environment, Helsinki, Finland • Icelandic Institute of Natural History, Reykjavik, Iceland • Ministry of the Environment and Nature, Greenland Homerule, Greenland (Kingdom of Denmark) • Russian Federation Ministry of Natural Resources, Moscow, Russia • Swedish Environmental Protection Agency, Stockholm, Sweden • United States Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Anchorage, Alaska This publication should be cited as: Merkel, F. and Barry, T. (eds.) 2008. Seabird harvest in the Arctic. CAFF International Secretariat, Circumpolar Seabird Group (CBird), CAFF Technical Report No. 16. Cover photo (F. Merkel): Thick-billed murres, Saunders Island, Qaanaaq, Greenland. For more information please contact: CAFF International Secretariat Borgir, Nordurslod 600 Akureyri, Iceland Phone: +354 462-3350 Fax: +354 462-3390 Email: [email protected] Internet: http://www.caff.is ___ CAFF Designated Area Editing: Flemming Merkel and Tom Barry Design & Layout: Tom Barry Seabird Harvest in the Arctic Prepared by the CIRCUMPOLAR SEABIRD GROUP (CBird) CAFF Technical Report No. 16 September 2008 List of Contributors Aever Petersen John W. Chardine The Icelandic Institute of Natural History Wildlife Research Division Hlemmur 3, P.O. Box 5320 Environment Canada IS-125 Reykjavik, ICELAND P.O. Box 6227 Email: [email protected], Tel: +354 5 900 500 Sackville, NB E4L 4K2 CANADA Bergur Olsen Email: [email protected], Tel: +1-506-364-5046 Faroese Fisheries Laboratory Nóatún 1, P.O.