Appendix: Yamamoto Ken (Baigai)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

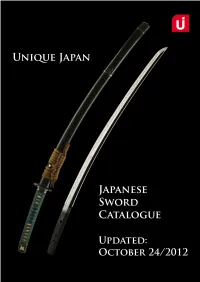

Antique Japanese Swords for Sale

! Antique Japanese Swords For Sale As of October 24, 2012 Tokyo, Japan The following pages contain descriptions of genuine antique Japanese swords currently available for ownership. Each sword can be legally owned and exported outside of Japan. Descriptions and availability are subject to change without notice. Please enquire for additional images and information on swords of interest to [email protected]. We look forward to assisting you. Pablo Kuntz Founder, unique japan Unique Japan, Fine Art Dealer Antiques license issued by Meguro City Tokyo, Japan (No.303291102398) Feel the history.™ uniquejapan.com ! Index of Japanese Swords for Sale # SWORDSMITH & TYPE CM CERTIFICATE ERA / PERIOD PRICE 1 A SADAHIDE GUNTO 68.0 NTHK Kanteisho 12th Showa (1937) ¥510,000 2 A KANETSUGU KATANA 73.0 NTHK Kanteisho Gendaito (~1940) ¥495,000 3 A KOREKAZU KATANA 68.7 Tokubetsu Hozon Shoho (1644~1648) ¥3,200,000 4 A SUKESADA KATANA 63.3 Tokubetsu Kicho 17th Eisho (1520) ¥2,400,000 5 A ‘FUYUHIRO’ TACHI 71.6 NTHK Kanteisho Tenbun (1532~1555) ¥1,200,000 6 A TADAKUNI KATANA 65.3 NBTHK Hozon Jokyo (1684~1688) ¥1,150,000 7 A MORIIE KATANA 71.0 NBTHK Hozon Eisho (1504~1521) ¥1,050,000 HOLD A TAKAHIRA KATANA 69.7 Tokubetsu Kicho 5th Kanai (1628) 9 A NOBUHIDE KATANA 72.1 NTHK Kanteisho 2nd Bunkyu (1862) ¥2,500,000 10 A KIYOMITSU KATANA 67.6 NBTHK Hozon 2nd Eiroku (1559) ¥2,500,000 SOLD A KANEUJI KATANA 69.8 NTHK Kanteisho Kyoho (1716~1735) ¥2,000,000 12 A NAOTSUNA KATANA 61.8 NTHK Kanteisho Oei (1394~1427) ¥600,000 13 A YOSHIKUNI KATANA 69.0 Keian (1648~1651) -

2006 Volkswagen Pro Tour Grand Finals Participating Players List (Updated As at 13/12/2006)

2006 Volkswagen Pro Tour Grand Finals Participating Players List (updated as at 13/12/2006) Men’s Singles Women’s Singles 01 MA Lin (CHN) ZHANG Yining (CHN) 02 WANG Liqin (CHN) WANG Yue Gu (SIN) 03 BOLL Timo (GER) *TIE Yana (HKG) 04 CHEN Qi (CHN) WANG Nan (CHN) 05 SAMSONOV Vladimir (BLR) LI Jia Wei (SIN) 06 WANG Hao (CHN) *JIANG Huajun (HKG) 07 HOU Yingchao (CHN) GUO Yan (CHN) 08 OH Sang Eun (KOR) LI Xiaoxia (CHN) 09 JOO Se Hyuk (KOR) LIU Jia (AUT) 10 CHEN Weixing (AUT) HIRANO Sayaka (JPN) 11 CHUAN Chih-Yuan (TPE) GAO Jun (USA) 12 SCHLAGER Werner (AUT) SHEN Yanfei (ESP) 13 *LI Ching (HKG) HIURA Reiko (JPN) 14 ELOI Damien (FRA) LI Jiao (NED) 15 GARDOS Robert (AUT) *ZHANG Rui (HKG) 16 KORBEL Petr (CZE) TAN MONFARDINI Wenling (ITA) Men’s Doubles Women’s Doubles 01 CHEN Qi / MA Lin (CHN) WANG Nan / ZHANG Yining (CHN) 02 CHEN Weixing / GARDOS Robert (AUT) *TIE Yana / ZHANG Rui (HKG) 03 *CHEUNG Yuk / LEUNG Chu Yan (HKG) GUO Yue / LI Xiaoxia (CHN) 04 *KO Lai Chak / LI Ching (HKG) LI Jia Wei / SUN Bei Bei (SIN) 05 BOLL Timo / SUSS Christian (GER) GAO Jun (USA) / SHEN Yanfei (ESP) 06 HAO Shuai / MA Long (CHN) HIRANO Sayaka / HIURA Reiko (JPN) 07 GAO Ning / YANG Zi (SIN) HEINE Veronika / LIU Jia (AUT) 08 AXELQVIST Johan / SVENSSON Robert (SWE) *LAU Sui Fei / LIN Ling (HKG) U21 Boys’ Singles U21 Girls’ Singles 01 *JIANG Tianyi (HKG) LI Qiangbing (AUT) 02 AXELQVIST Johan (SWE) POTA Georgina (HUN) 03 BAUM Patrick (GER) GRUNDISCH Carole (FRA) 04 BOBILLIER Loïc (FRA) RAMIREZ Sara (ESP) 05 JAKAB Janos (HUN) VACENOVSKA Iveta (CZE) 06 KIM Tae Hoon (KOR) *YU Kwok See (HKG) 07 MATSUMOTO Cazuo (BRA) HEINE Veronika (AUT) 08 DURAN Marc (ESP) PROKHOROVA Yulia (RUS) . -

TABLE TENNIS Ολυµπιακό Γυµναστήριο Γαλατσίου Επιτραπέζια Αντισφαίριση / TENNIS DE TABLE Gymnase Olympique De Galatsi

Galatsi Olympic Hall TABLE TENNIS Ολυµπιακό Γυµναστήριο Γαλατσίου Επιτραπέζια Αντισφαίριση / TENNIS DE TABLE Gymnase Olympique de Galatsi Medallists by Event Κάτοχοι Μεταλλίων ανά Αγώνισµα / Médaillés par épreuve AFTER 4 OF 4 EVENTS As of 23 AUG 2004 NOC Event Name Date Medal Name Code WANG Nan Women's Doubles 20 AUG 2004 GOLD CHN ZHANG Yining LEE Eun Sil SILVER KOR SEOK Eun Mi GUO Yue BRONZE CHN NIU Jianfeng CHEN Qi Men's Doubles 21 AUG 2004 GOLD CHN MA Lin KO Lai Chak SILVER HKG LI Ching MAZE Michael BRONZE DEN TUGWELL Finn Women's Singles 22 AUG 2004 GOLD ZHANG Yining CHN SILVER KIM Hyang Mi PRK BRONZE KIM Kyung Ah KOR Men's Singles 23 AUG 2004 GOLD RYU Seung Min KOR SILVER WANG Hao CHN BRONZE WANG Liqin CHN TT0000000_C93.4.0 Report Created MON 23 AUG 2004 14:50 Page 1/1 Galatsi Olympic Hall TABLE TENNIS Ολυµπιακό Γυµναστήριο Γαλατσίου Επιτραπέζια Αντισφαίριση / TENNIS DE TABLE Gymnase Olympique de Galatsi Medal Standings Κατάταξη Μεταλλίων / Répartition des médailles AFTER 4 OF 4 EVENTS As of MON 23 AUG 2004 Men Women Total Rank Rank NOC By G S B Tot G S B Tot G S B Tot Total 1 CHN - China 1 1 1 3 2 1 3 3 1 2 6 1 2 KOR - Korea 1 1 1 1 2 1 1 1 3 2 3 HKG - Hong Kong 1 1 1 1 =3 3 PRK - DPR Korea 1 1 1 1 =3 5 DEN - Denmark 1 1 1 1 =3 Total 2 2 2 6 2 2 2 6 4 4 4 12 Legend: G - Gold S - Silver B - Bronze Tot - Total '=' - Equal sign indicates that two or more player's NOCs share the same rank by total TT_C95 4.0 Report Created MON 23 AUG 2004 14:50 Page 1/1 Galatsi Olympic Hall TABLE TENNIS Ολυµπιακό Γυµναστήριο Γαλατσίου Επιτραπέζια Αντισφαίριση / TENNIS DE TABLE Gymnase Olympique de Galatsi 22 Aug. -

Japonica Humboldtiana 8 (2004)

JAPONICA HUMBOLDTIANA 8 (2004) Contents MARKUS RÜTTERMANN Ein japanischer Briefsteller aus dem ‘Tempel zu den hohen Bergen’ Übersetzung und Kommentar einer Heian-zeitlichen Handschrift (sogenanntes Kôzanjibon koôrai). Zweiter und letzter Teil ............ 5 GERHILD ENDRESS Ranglisten für die Regierungsbeamten des Hofadels Ein textkritischer Bericht über das Kugyô bunin ............................. 83 STEPHAN KÖHN Alles eine Frage des Geschmacks Vom unterschiedlichen Stellenwert der Illustration in den vormodernen Literaturen Ost- und Westjapans .................... 113 HARALD SALOMON National Policy Films (kokusaku eiga) and Their Audiences New Developments in Research on Wartime Japanese Cinema.............................................................................. 161 KAYO ADACHI-RABE Der Kameramann Miyagawa Kazuo................................................ 177 Book Reviews SEPP LINHART Edo bunko. Die Edo Bibliothek. Ausführlich annotierte Bibliographie der Blockdruckbücher im Besitz der Japanologie der J. W. Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main als kleine Bücherkunde und Einführung in die Verlagskultur der Edo-Zeit Herausgegeben von Ekkehard MAY u.a............................................ 215 4 Contents REGINE MATHIAS Zur Diskussion um die “richtige” Geschichte Japans Steffi RICHTER und Wolfgang HÖPKEN (Hg.): Vergangenheit im Gesellschaftskonflikt. Ein Historikerstreit in Japan; Christopher BARNARD: Language, Ideology, and Japanese History Textbooks ........................................................................... -

No. Venue Year Men's Team Women's Team Men's Singles

Asian Championships Results 1972 to 2007 No. Venue Year Men's Team Women's Men's Team Singles 1. Beijing 1972 Japan China HASEGAWA Nabuhiko (JPN) bt China bt Japan bt XI Enting (CHN) 2. Yokohama 1974 China Japan HASEGAWA Nabuhiko (JPN) Bt Japan Bt China bt XI Enting (CHN) 3. Pyongyang 1976 China Korea DPR LIANG Geliang (CHN) bt Japan bt China bt GUO Yuehua (CHN) 4. Kuala Lumpur 1978 China China GUO Yuehua(CHN) Bt Korea DPR Bt Korea DPR bt LIANG Geliang (CHN) 5. Calcutta 1980 China China SHI Zhihao (CHN) bt Japan bt Korea DPR bt XIE Saike (CHN) 6. Jakarta 1982 China China CAI Zhenhua (CHN) bt Japan bt Japan bt XIE Saike (CHN) 7. Islamabad 1984 China China XIE Saike (CHN) bt Korea DPR bt Korea DPR bt CHEN Longcan (CHN) 8. Shenzhen 1986 China China J1ANG Jialiang (CHN) bt Korea DPR bt Korea DPR bt TENG Yi (CHN) 9. Niigata 1988 China Korea R CHEN Longcan (CHN) bt Korea DPR bt Korea DPR Bt YOO Nam Kyu (KOR) 10. Kuala Lumpur 1990 China Korea R WANG Tao (CHN) bt Korea DPR bt Korea DPR bt MA Wenge (CHN) 11. New Delhi 1992 China Hong Kong XIE Chaojie (CHN) bt Korea DPR bt China bt KANG Hee Chan (KOR) 12. Tianjin 1994 China China KONG Linghui (CHN) bt Korea DPR bt Hong Kong bt LIU Guoliang (CHN) 13 Singapore 1996 Korea China Kong Linghui(CHN) Bt China Bt Hong Kong Bt Liu Guoliang(CHN) 14 Osaka 1998 China China WANG Liqin(CHN) Bt Korea R Bt Korea DPR Bt Seiko Iseki(JPN) 15 Doha 2000 China China CHIANG Peng-Lung(TPE) Bt Korea Bt Korea Bt MA Lin(CHN) 16 Bangkok 2003 China Bt China Bt Wang Hao(CHN) Chinese Taipei Hongkong,China Bt Tang Peng(CHN) 17 -

Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J

Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei mandara Talia J. Andrei Submitted in partial fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences Columbia University 2016 © 2016 Talia J.Andrei All rights reserved Abstract Mapping Sacred Spaces: Representations of Pleasure and Worship in Sankei Mandara Talia J. Andrei This dissertation examines the historical and artistic circumstances behind the emergence in late medieval Japan of a short-lived genre of painting referred to as sankei mandara (pilgrimage mandalas). The paintings are large-scale topographical depictions of sacred sites and served as promotional material for temples and shrines in need of financial support to encourage pilgrimage, offering travelers worldly and spiritual benefits while inspiring them to donate liberally. Itinerant monks and nuns used the mandara in recitation performances (etoki) to lead audiences on virtual pilgrimages, decoding the pictorial clues and touting the benefits of the site shown. Addressing themselves to the newly risen commoner class following the collapse of the aristocratic order, sankei mandara depict commoners in the role of patron and pilgrim, the first instance of them being portrayed this way, alongside warriors and aristocrats as they make their way to the sites, enjoying the local delights, and worship on the sacred grounds. Together with the novel subject material, a new artistic language was created— schematic, colorful and bold. We begin by locating sankei mandara’s artistic roots and influences and then proceed to investigate the individual mandara devoted to three sacred sites: Mt. Fuji, Kiyomizudera and Ise Shrine (a sacred mountain, temple and shrine, respectively). -

A New Interpretation of the Bakufu's Refusal to Open the Ryukyus To

Volume 16 | Issue 17 | Number 3 | Article ID 5196 | Sep 01, 2018 The Asia-Pacific Journal | Japan Focus A New Interpretation of the Bakufu’s Refusal to Open the Ryukyus to Commodore Perry Marco Tinello Abstract The Ryukyu Islands are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to In this article I seek to show that, while the Taiwan. The former Kingdom of Ryukyu was Ryukyu shobun refers to the process by which formally incorporated into the Japanese state the Meiji government annexed the Ryukyu as Okinawa Prefecture in 1879. Kingdom between 1872 and 1879, it can best be understood by investigating its antecedents in the Bakumatsu era and by viewing it in the wider context of East Asian and world history. I show that, following negotiations with Commodore Perry, the bakufu recognized the importance of claiming Japanese control over the Ryukyus. This study clarifies the changing nature of Japanese diplomacy regarding the Ryukyus from Bakumatsu in the late 1840s to early Meiji. Keywords Tokugawa bakufu, Bakumatsu, Ryukyu shobun, Commodore Perry, Japan From the end of the fourteenth century until the mid-sixteenth century, the Ryukyu kingdom was a center of trade relations between Japan, China, Korea, and other East Asian partners. According to his journal, when Commodore Matthew C. Perry demanded that the Ryukyu Islands be opened to his fleet in 1854, the Tokugawa shogunate replied that the Ryukyu Kingdom “is a very distant country, and the opening of its harbor cannot be discussed by us.”2 The few English-language studies3 of this encounter interpret this reply as evidence that 1 16 | 17 | 3 APJ | JF the bakufu was reluctant to become involved in and American sources relating to the discussions about the international status of negotiations between Perry and the bakufu in the Ryukyus; no further work has been done to 1854, I show that Abe did not draft his guide investigate the bakufu’s foreign policy toward immediately before, but rather after the Ryukyus between 1854 and the early Meiji negotiations were held at Uraga in 1854/2. -

Tetsugaku International Journal of the Philosophical Association of Japan

ISSN 2432-8995 Tetsugaku International Journal of the Philosophical Association of Japan Volume 2 2018 Special Theme Philosophy and Translation The Philosophical Association of Japan The Philosophical Association of Japan PRESIDENT KATO Yasushi (Hitotsubashi University) CHIEF OF THE EDITORIAL COMITTEE ICHINOSE Masaki (Musashino University) Tetsugaku International Journal of the Philosophical Association of Japan EDITORIAL BOARD CHIEF EDITOR NOTOMI Noburu (University of Tokyo) DEPUTY CHIEF EDITORS Jeremiah ALBERG (International Christian University) BABA Tomokazu (University of Nagano) SAITO Naoko (Kyoto University) BOARD MEMBERS DEGUCHI Yasuo (Kyoto University) FUJITA Hisashi (Kyushu Sangyo University) MURAKAMI Yasuhiko (Osaka University) SAKAKIBARA Tetsuya (University of Tokyo) UEHARA Mayuko (Kyoto University) ASSISTANT EDITOR TSUDA Shiori (Hitotsubashi University) SPECIAL THANKS TO Beverly Curran (International Christian University), Andrea English (University of Edingburgh), Enrico Fongaro (Tohoku University), Naomi Hodgson (Liverpool Hope University), Leah Kalmanson (Drake University), Sandra Laugier (Paris 1st University Sorbonne), Áine Mahon (University College Dublin), Mathias Obert (National University of Kaohsiung), Rossen Roussev (University of Veliko Tarnovo), Joris Vlieghe (University of Aberdeen), Yeong-Houn Yi (Korean University), Emma Williams (University of Warwick) Tetsugaku International Journal of the Philosophical Association of Japan Volume 2, Special Theme: Philosophy and Translation April 2018 Edited and published -

The Making of Modern Japan

The Making of Modern Japan The MAKING of MODERN JAPAN Marius B. Jansen the belknap press of harvard university press Cambridge, Massachusetts London, England Copyright © 2000 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America Third printing, 2002 First Harvard University Press paperback edition, 2002 Book design by Marianne Perlak Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jansen, Marius B. The making of modern Japan / Marius B. Jansen. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 0-674-00334-9 (cloth) isbn 0-674-00991-6 (pbk.) 1. Japan—History—Tokugawa period, 1600–1868. 2. Japan—History—Meiji period, 1868– I. Title. ds871.j35 2000 952′.025—dc21 00-041352 CONTENTS Preface xiii Acknowledgments xvii Note on Names and Romanization xviii 1. SEKIGAHARA 1 1. The Sengoku Background 2 2. The New Sengoku Daimyo 8 3. The Unifiers: Oda Nobunaga 11 4. Toyotomi Hideyoshi 17 5. Azuchi-Momoyama Culture 24 6. The Spoils of Sekigahara: Tokugawa Ieyasu 29 2. THE TOKUGAWA STATE 32 1. Taking Control 33 2. Ranking the Daimyo 37 3. The Structure of the Tokugawa Bakufu 43 4. The Domains (han) 49 5. Center and Periphery: Bakufu-Han Relations 54 6. The Tokugawa “State” 60 3. FOREIGN RELATIONS 63 1. The Setting 64 2. Relations with Korea 68 3. The Countries of the West 72 4. To the Seclusion Decrees 75 5. The Dutch at Nagasaki 80 6. Relations with China 85 7. The Question of the “Closed Country” 91 vi Contents 4. STATUS GROUPS 96 1. The Imperial Court 97 2. -

Japanese Confucianism Kiri Paramore Index More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-05865-1 — Japanese Confucianism Kiri Paramore Index More Information Index Action Française, 189 religious and political vision, 30 agricultural innovation and reform, 51 rise of, 44 alternate attendance system social reading, 89 (sankinko¯tai),70 Tendai Buddhism, 38 American Civil War, 124 Way of Heaven texts and, 50 Amino Yoshihiko, 23 Zen Buddhism, 17, 31, 32–35, 38 anti-Christian tradition in bunbu ryo¯do¯, 72, 82 Japan, 148 Bushi practice, 136 anti-elitism, 176 anti-Semitism, 9 capitalism, 119, 130–136, 188 anti-Siniticism, 9. see also Sinophobia carnal desire, 80 anti-Western sentiment, 119 Catholicism, 47. see also Christianity Arai Hakuseki, 47, 101 “Central Kingdom” (chu¯goku), 64, 175 Asai no So¯zui, 96 Cheng Hao, 45, 52, 111 Association for the Propagation of Japanese Cheng Yi, 45, 52, 60, 111 Confucianism Nihon jukyo¯senyo¯ Cheng Ziming, 96, 99 kai, 157 Chiang Kai-shek, 160, 165, 188, 189 authoritarianism, 166, 191 Chikamatsu Monzaemon, 75–77 China, occupied, 161–162 Ban Gu, 5 Chinese Civil War, 174 Bansho wage goyo¯ (barbarian document Chinese Communist Party (CCP), 10, translation service), 108 159, 186 Barbarian Documents Research Center Chinese Confucianism, 185–191. see also (bansho shirabesho). see Shogunal East Asian Confucianism Institute of Western Learning Chinese dynastic codes, 26 barbarian identity, 22–23 Chinese Nationalist Party (KMT), 159, Bencao (Herb Canon), 109 161–162, 186 Bingo Mihara Rebellion, 91 Choson Korea, 66, 163 Bito¯Jishu¯, 78, 87, 88, 92 Christianity Bodart-Bailey, -

Newsletter August 2007 B Engl.Pmd

In this issue: NEWS Interview Shunsaku Yamada 02 Butterfly World Chef 08 2007 News/WRL July 2007 04 www.timo-boll.de now also in Chinese writing Timo Boll´s Column - News 05 The development of his career and a request from China, the mother country of the table Stars under the magnifer 06 tennis sport lead Timo Boll to a complete Timo Boll: Forehand with a wide sidestep II revision of his internet appearance on www.timo-boll.de. Major parts of the contents are now on offer in Chinese writing. Products of the month 10 The technical realisation is in the hands of kaliber5 GmbH, Hamburg. Bernhard Schmittenbecher who is responsible for the media work for Timo Boll produces Tips and Tricks: 12 the content. This re-launch is the result of the increasing interest in Timo Boll in World Champion Werner Schlager China. Butterfly Inside 14 Interview: Zhang Mo, Canada www.butterfly-world.com Redaktion/Editor - Am Schürmannshütt 30 h - D-47441 Moers - Germany - Phone: +49 2841 90532-0 - Mail: [email protected] 02 Interview Interview Shunsaku Yamada Butterfly World 23. August - 26. August 2007 Shunsaku Yamada, 54, married and father of two daughters has been Pro Tour: Chinese Taipei Open working for Tamasu Butterfly Co. Ltd for 30 years. Before he was elected president of the Tamasu Company in December 2005 he was 30. August - 02. September 2007 chief of production and leader of the factory of the well-known Pro Tour: Panasonic China Open Japanese company. In the 57 year old history of the company he is rd only the 3 president whose name is not Tamasu. -

CHINA VANKE CO., LTD.* 萬科企業股份有限公司 (A Joint Stock Company Incorporated in the People’S Republic of China with Limited Liability) (Stock Code: 2202)

Hong Kong Exchanges and Clearing Limited and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited take no responsibility for the contents of this announcement, make no representation as to its accuracy or completeness and expressly disclaim any liability whatsoever for any loss howsoever arising from or in reliance upon the whole or any part of the contents of this announcement. CHINA VANKE CO., LTD.* 萬科企業股份有限公司 (A joint stock company incorporated in the People’s Republic of China with limited liability) (Stock Code: 2202) 2019 ANNUAL RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT The board of directors (the “Board”) of China Vanke Co., Ltd.* (the “Company”) is pleased to announce the audited results of the Company and its subsidiaries for the year ended 31 December 2019. This announcement, containing the full text of the 2019 Annual Report of the Company, complies with the relevant requirements of the Rules Governing the Listing of Securities on The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited in relation to information to accompany preliminary announcement of annual results. Printed version of the Company’s 2019 Annual Report will be delivered to the H-Share Holders of the Company and available for viewing on the websites of The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (www.hkexnews.hk) and of the Company (www.vanke.com) in April 2020. Both the Chinese and English versions of this results announcement are available on the websites of the Company (www.vanke.com) and The Stock Exchange of Hong Kong Limited (www.hkexnews.hk). In the event of any discrepancies in interpretations between the English version and Chinese version, the Chinese version shall prevail, except for the financial report prepared in accordance with International Financial Reporting Standards, of which the English version shall prevail.