Evaluating Violence in Slasher Films: Similarity and Social Identification with the Final Girl

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Girl in the Woods: on Fairy Stories and the Virgin Horror

Journal of Tolkien Research Volume 10 Issue 1 J.R.R. Tolkien and the works of Joss Article 3 Whedon 2020 The Girl in the Woods: On Fairy Stories and the Virgin Horror Brendan Anderson University of Vermont, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch Recommended Citation Anderson, Brendan (2020) "The Girl in the Woods: On Fairy Stories and the Virgin Horror," Journal of Tolkien Research: Vol. 10 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://scholar.valpo.edu/journaloftolkienresearch/vol10/iss1/3 This Peer-Reviewed Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Christopher Center Library at ValpoScholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Tolkien Research by an authorized administrator of ValpoScholar. For more information, please contact a ValpoScholar staff member at [email protected]. Anderson: The Girl in the Woods THE GIRL IN THE WOODS: ON FAIRY STORIES AND THE VIRGIN HORROR INTRODUCTION The story is an old one: the maiden, venturing out her door, ignores her guardian’s prohibitions and leaves the chosen path. Fancy draws her on. She picks the flow- ers. She revels in her freedom, in the joy of being young. Then peril appears—a wolf, a monster, something with teeth for gobbling little girls—and she learns, too late, there is more to life than flowers. The girl is destroyed, but then—if she is lucky—she returns a woman. According to Maria Tatar (while quoting Catherine Orenstein): “the girl in the woods embodies ‘complex and fundamental human concerns’” (146), a state- ment at least partly supported by its appearance in the works of both Joss Whedon and J.R.R. -

This Installation Explores the Final Girl Trope. Final Girls Are Used in Horror Movies, Most Commonly Within the Slasher Subgenre

This installation explores the final girl trope. Final girls are used in horror movies, most commonly within the slasher subgenre. The final girl archetype refers to a single surviving female after a murderer kills off the other significant characters. In my research, I focused on the five most iconic final girls, Sally Hardesty from A Texas Chainsaw Massacre, Laurie Strode from Halloween, Ellen Ripley from Alien, Nancy Thompson from A Nightmare on Elm Street and Sidney Prescott from Scream. These characters are the epitome of the archetype and with each girl, the trope evolved further into a multilayered social commentary. While the four girls following Sally added to the power of the trope, the significant majority of subsequent reproductions featured surface level final girls which took value away from the archetype as a whole. As a commentary on this devolution, I altered the plates five times, distorting the image more and more, with the fifth print being almost unrecognizable, in the same way that final girls have become. Chloe S. New Jersey Blood, Tits, and Screams: The Final Girl And Gender In Slasher Films Chloe S. Many critics would credit Hitchcock’s 1960 film Psycho with creating the genre but the golden age of slasher films did not occur until the 70s and the 80s1. As slasher movies became ubiquitous within teen movie culture, film critics began questioning why audiences, specifically young ones, would seek out the high levels of violence that characterized the genre.2 The taboo nature of violence sparked a powerful debate amongst film critics3, but the most popular, and arguably the most interesting explanation was that slasher movies gave the audience something that no other genre was able to offer: the satisfaction of unconscious psychological forces that we must repress in order to “function ‘properly’ in society”. -

How to Die in a Slasher Film: the Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol

Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol. 21 (Issue 1): pp. 128 – 146 Wellman, Meitl, & Kinkade Copyright © 2021 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture All rights reserved. ISSN: 1070-8286 How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization, Strength, and Flaws on Characters’ Mortality Ashley Wellman Texas Christian University & Michele Bisaccia Meitl Texas Christian University & Patrick Kinkade Texas Christian University 128 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture How to Die in a Slasher Film: The Impact of Sexualization July, 2021, Vol. 21 (Issue 1): pp. 128 – 146 Wellman, Meitl, & Kinkade Abstract Popular culture has often referenced formulaic ways to predict a character’s fate in slasher films. The cliché rules have noted only virgins live, black characters die first, and drinking and drugs nearly guarantee your death, but to what extent do characters’ basic demographics and portrayal determine whether a character lives or dies? A content analysis of forty-eight of the most influential slasher films from the 1960s – 2010s was conducted to measure factors related to character mortality. From these films, gender, race, sexualization (measured via specific acts and total sexualization), strength, and flaws were coded for 504 non killer characters. Results indicate that the factors predicting death vary by gender. For male characters, those appearing weak in terms of physical strength or courage and those males who appeared morally flawed were more likely to die than males that were strong and morally sound. Predictors of death for female characters included strength and the presence of sexual behavior (including dress, flirtatious attitude, foreplay/sex, nudity, and total sexualization). -

A Dark New World : Anatomy of Australian Horror Films

A dark new world: Anatomy of Australian horror films Mark David Ryan Faculty of Creative Industries, Queensland University of Technology A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the degree Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), December 2008 The Films (from top left to right): Undead (2003); Cut (2000); Wolf Creek (2005); Rogue (2007); Storm Warning (2006); Black Water (2007); Demons Among Us (2006); Gabriel (2007); Feed (2005). ii KEY WORDS Australian horror films; horror films; horror genre; movie genres; globalisation of film production; internationalisation; Australian film industry; independent film; fan culture iii ABSTRACT After experimental beginnings in the 1970s, a commercial push in the 1980s, and an underground existence in the 1990s, from 2000 to 2007 contemporary Australian horror production has experienced a period of strong growth and relative commercial success unequalled throughout the past three decades of Australian film history. This study explores the rise of contemporary Australian horror production: emerging production and distribution models; the films produced; and the industrial, market and technological forces driving production. Australian horror production is a vibrant production sector comprising mainstream and underground spheres of production. Mainstream horror production is an independent, internationally oriented production sector on the margins of the Australian film industry producing titles such as Wolf Creek (2005) and Rogue (2007), while underground production is a fan-based, indie filmmaking subculture, producing credit-card films such as I know How Many Runs You Scored Last Summer (2006) and The Killbillies (2002). Overlap between these spheres of production, results in ‘high-end indie’ films such as Undead (2003) and Gabriel (2007) emerging from the underground but crossing over into the mainstream. -

Halloween Should Be Spooky, Not Scary! Governor Cuomo Asks for Your Help to Make Sure Everyone Has a Healthy and Safe Halloween

Halloween should be spooky, not scary! Governor Cuomo asks for your help to make sure everyone has a healthy and safe Halloween. Halloween celebrations and activities, including trick-or-treating, can be filled with fun, but must be done in a safe way to prevent the spread of COVID-19. The best way to celebrate Halloween this year is to have fun with the people who live in your household. Decorating your house or apartment, decorating and carving pumpkins, playing Halloween-themed games, watching spooky movies, and trick-or-treating through your house or in a backyard scavenger hunt are all fun and healthy ways to celebrate during this time. Creative ways to celebrate more safely: • Organize a virtual Halloween costume party with costumes and games. • Have a neighborhood car parade or vehicle caravan where families show off their costumes while staying socially distanced and remaining in their cars. • In cities or apartment buildings, communities can come together to trick-or-treat around the block or other outdoor spaces so kids and families aren’t tempted to trick-or-treat inside – building residents & businesses can contribute treats that are individually wrapped and placed on a table(s) outside of the front door of the building, or in the other outdoor space for grab and go trick-or-treating. • Make this year even more special and consider non-candy Halloween treats that your trick- or-treaters will love, such as spooky or glittery stickers, magnets, temporary tattoos, pencils/ erasers, bookmarks, glow sticks, or mini notepads. • Create a home or neighborhood scavenger hunt where parents or guardians give their kids candy when they find each “clue.” • Go all out to decorate your house this year – have a neighborhood contest for the best decorated house. -

Running Head: HORROR and HALLOWEEN 1 Horror, Halloween

Running head: HORROR AND HALLOWEEN 1 Horror, Halloween, and Hegemony: A Psychoanalytical Profile and Empirical Gender Study of the “Final Girls” in the Halloween Franchise Tabatha Lehmann Department of Psychology Dr. Patrick L. Smith Thesis for completion of the Honors Program Florida Southern College April 29, 2021 HORROR AND HALLOWEEN 2 Abstract The purpose of this study is to determine how the perceptions of femininity have changed throughout time. This can be made possible through a psychoanalysis of the main character of Halloween, Laurie Strode, and other female characters from the original Halloween film released in 1978 to the more recent sequel announced in 2018. Previous research has shown that horror films from the slasher genre in the 1970s and 1980s have historically depicted men and women as displaying behaviors that are largely indicative of their gender stereotypes (Clover, 1997; Connelly, 2007). Men are typically the antagonists of these films, and display perceptible aggression, authority, and physical strength; on the contrary, women generally play the victims, and are usually portrayed as weaker, more subordinate, and often in a role that perpetuates the classic stereotypes of women as more submissive to males and as being more emotionally stricken during perceived traumatic events (Clover, 1997; Lizardi, 2010; Rieser, 2001; Williams, 1991). Research has also shown that the “Final Girl” in horror films—the last girl left alive at the end of the movie—has been depicted as conventionally less feminine compared to other female characters featured in these films (De Muzio, 2006; Lizardi, 2010). This study found that Laurie Strode in 1978 was more highly rated on a gender role scale for feminine characteristics, while Laurie Strode in 2018 was found to have had significantly higher rating for masculine word descriptors than feminine. -

Read an Excerpt

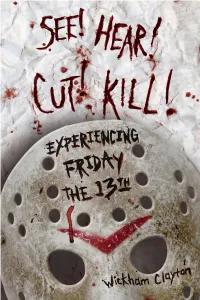

Univer�it y Pre� of Mis �is �ipp � / Jacks o� Contents u Preface: This book could be for you, depending on how you read it . ix. Acknowledgments . .xiii Chapter 1 Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy . 3 Chapter 2 Jason’s Mechanical Eye . 45 Chapter 3 Hearing Cutting . .83 . Chapter 4 Have You Met Jason? . 119. Chapter 5 The Importance of Being Jason . 153 .. Appendix 1 Plot Summaries for the Friday the 13th Films . 179 Appendix 2 List and Description of Characters in the Friday the 13th Films . 185 Works Cited . 199 Index . 217. Chapter 1 u Meet Jason Voorhees: An Autopsy Sometimes the weirdest movies strike you in unexpected ways. In the winter of 1997, I attended a late-night screening of Friday the 13th (1980) at the campus theater at James Madison University in Harrisonburg, Virginia. I’d never seen the film before, but I was aware of its cultural significance. I expected a generic slasher film with extensive violence and nudity. I expected something ultimately forgettable. Having watched it seventeen years after its initial release, I found it generic; it did have violence and nudity, and was entertaining. However, I did not find it forgettable. Walking home with the first flecks of a winter snow weaving around me in the dark, I found myself thinking over it. I continually recalled images, sounds, and narrative moments that were vivid in my mind. Friday the 13th wormed into my brain, with its haunting and atmospheric style. After watching the original film several more times, I started in on the sequels, preparing myself for disappointment each time. -

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Friday the 13Th Part II by Simon Hawke Friday the 13Th Part 2 Review

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Friday the 13th Part II by Simon Hawke Friday the 13th part 2 review. Vickie didnt want to disturb Jeff and Sandra. She had heard the vigorous sounds coming from their bedroom, and knew they must be lying exhausted in each others arms by now. But she had to see them. She had to warn them what was happening here at Crystal Lake, as thunder crashed and lightning flashed. Timidly she opened the bedroom door and looked inside. The sheets were pulled over two figures lying on the bed. Sandra, Vickie whispered. Then the sheet was thrown back, and a hooded figure sat up. and Vickie screamed and screamed and screamed. Dr. Wolfula- "Friday the 13th Part 2" Review. User Reviews. Check out what Sophie had to say about the corresponding Freddy pic here! With Mrs. Voorhees with no head and a cliffhanger of an ending, writer Ron Kurz and director Steve Miner had a few roads to travel in unraveling more of the slasher franchise. The camp slasher foundation continues its build, but the introduction of a soon to be iconic killer makes the film feel fresh and exciting with a surprising attention to detail. Alice Hardy has survived the attacks of crazy Mrs. Voorhees and decides to gain back her normalcy in a summer vacation home. The dream of a decomposed young Jason still haunt her, as does the head of Pamela flying from her neck. Forgot your password? Don't have an account? Sign up here. By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes and Fandango. -

Gender Differences in Descriptions and Perceptions of Slasher Films

Fear and Loathing at the Cinemaplex: Gender Differences in Descriptions and Perceptions of Slasher Films Justin M. Nolan Gery W. Ryan Department of Anthropology University of Missouri – Columbia ã May 1999 Submitted to: Sex Roles Please do not cite without authors’ permission. Direct Comments to: Justin Nolan Dept of Anthropology 107 Swallow Hall University of Missouri Columbia, MO 65211 Phone: (573)445-4625 Email: [email protected] Abstract This study investigates gender-specific descriptions and perceptions of slasher films. Sixty American undergraduate and graduate students, 30 males and 30 females, were asked to recount in a written survey the details of the most memorable slasher film they remember watching, and to describe the emotional reactions evoked by that film. A text analysis approach was used to examine and interpret informant responses. Males recall a high percentage of descriptive images associated with what is called “rural terror,” a a concept tied to fear of strangers and rural places, while females display greater fear of “family terror,” including the themes of betrayed intimacy and spiritual possession. It is found that females report a higher level and a greater number of fear reactions than males, who report more anger and frustration responses. Gender-specific fears as personalized through slasher film recall are discussed with relation to socialization practices and power-control theory. 2 Introduction "Sally is the only survivor of a night of murder and madness; she is captured and tortured by the cannibals in a grisly parody of the Mad Tea Party, but manages to escape and, after a harrowing pursuit down a back road, is rescued by a passing truck driver. -

Gorinski2018.Pdf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Automatic Movie Analysis and Summarisation Philip John Gorinski I V N E R U S E I T H Y T O H F G E R D I N B U Doctor of Philosophy Institute for Language, Cognition and Computation School of Informatics University of Edinburgh 2017 Abstract Automatic movie analysis is the task of employing Machine Learning methods to the field of screenplays, movie scripts, and motion pictures to facilitate or enable vari- ous tasks throughout the entirety of a movie’s life-cycle. From helping with making informed decisions about a new movie script with respect to aspects such as its origi- nality, similarity to other movies, or even commercial viability, all the way to offering consumers new and interesting ways of viewing the final movie, many stages in the life-cycle of a movie stand to benefit from Machine Learning techniques that promise to reduce human effort, time, or both. -

Volume 8, Number 1

POPULAR CULTURE STUDIES JOURNAL VOLUME 8 NUMBER 1 2020 Editor Lead Copy Editor CARRIELYNN D. REINHARD AMY DREES Dominican University Northwest State Community College Managing Editor Associate Copy Editor JULIA LARGENT AMANDA KONKLE McPherson College Georgia Southern University Associate Editor Associate Copy Editor GARRET L. CASTLEBERRY PETER CULLEN BRYAN Mid-America Christian University The Pennsylvania State University Associate Editor Reviews Editor MALYNNDA JOHNSON CHRISTOPHER J. OLSON Indiana State University University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Associate Editor Assistant Reviews Editor KATHLEEN TURNER LEDGERWOOD SARAH PAWLAK STANLEY Lincoln University Marquette University Associate Editor Graphics Editor RUTH ANN JONES ETHAN CHITTY Michigan State University Purdue University Please visit the PCSJ at: mpcaaca.org/the-popular-culture-studies-journal. Popular Culture Studies Journal is the official journal of the Midwest Popular Culture Association and American Culture Association (MPCA/ACA), ISSN 2691-8617. Copyright © 2020 MPCA. All rights reserved. MPCA/ACA, 421 W. Huron St Unit 1304, Chicago, IL 60654 EDITORIAL BOARD CORTNEY BARKO KATIE WILSON PAUL BOOTH West Virginia University University of Louisville DePaul University AMANDA PICHE CARYN NEUMANN ALLISON R. LEVIN Ryerson University Miami University Webster University ZACHARY MATUSHESKI BRADY SIMENSON CARLOS MORRISON Ohio State University Northern Illinois University Alabama State University KATHLEEN KOLLMAN RAYMOND SCHUCK ROBIN HERSHKOWITZ Bowling Green State Bowling Green State -

Friday the 13Th: Resurrection Table of Contents TABLE of CONTENTS

Friday the 13th Resurrection V0.5 By Michael Tresca D20 System and D&D is a trademark of Wizards of the Coast, Inc.©. All original Friday the 13th images and logos are copyright of their respected companies: © 2000/2001 Crystal Lake Entertainment / New Line Cinema. All Rights Reserved. Trademarks and copyrights are cited in this document without permission. This usage is not meant in any way to challenge the rightful ownership of said trademarks/copyrights. All copyrights are acknowledged and remain the property of the owners. Epic Undead Jason Voorhees, Corpse template, and the Slasher class were created by DarkSoldier's D20 Modern Netbook of Famous Characters. This game is for entertainment only. This document utilizes the Friday the 13th and Ghosttown fonts. You can get the latest version of this document at Talien's Tower, under the Freebies section. WARNING: This document contains spoilers of the movies and games. There. You've been warned! 2 - Friday the 13th: Resurrection Table of Contents TABLE OF CONTENTS................................................................................................................................3 INTRODUCTION...........................................................................................................................................6 SUMMARY ....................................................................................................................................................6 CAMPAIGN IN BRIEF......................................................................................................................................6