Gender Differences in Descriptions and Perceptions of Slasher Films

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Friday the 13Th Part II by Simon Hawke Friday the 13Th Part 2 Review

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Friday the 13th Part II by Simon Hawke Friday the 13th part 2 review. Vickie didnt want to disturb Jeff and Sandra. She had heard the vigorous sounds coming from their bedroom, and knew they must be lying exhausted in each others arms by now. But she had to see them. She had to warn them what was happening here at Crystal Lake, as thunder crashed and lightning flashed. Timidly she opened the bedroom door and looked inside. The sheets were pulled over two figures lying on the bed. Sandra, Vickie whispered. Then the sheet was thrown back, and a hooded figure sat up. and Vickie screamed and screamed and screamed. Dr. Wolfula- "Friday the 13th Part 2" Review. User Reviews. Check out what Sophie had to say about the corresponding Freddy pic here! With Mrs. Voorhees with no head and a cliffhanger of an ending, writer Ron Kurz and director Steve Miner had a few roads to travel in unraveling more of the slasher franchise. The camp slasher foundation continues its build, but the introduction of a soon to be iconic killer makes the film feel fresh and exciting with a surprising attention to detail. Alice Hardy has survived the attacks of crazy Mrs. Voorhees and decides to gain back her normalcy in a summer vacation home. The dream of a decomposed young Jason still haunt her, as does the head of Pamela flying from her neck. Forgot your password? Don't have an account? Sign up here. By creating an account, you agree to the Privacy Policy and the Terms and Policies , and to receive email from Rotten Tomatoes and Fandango. -

Gorinski2018.Pdf

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. Automatic Movie Analysis and Summarisation Philip John Gorinski I V N E R U S E I T H Y T O H F G E R D I N B U Doctor of Philosophy Institute for Language, Cognition and Computation School of Informatics University of Edinburgh 2017 Abstract Automatic movie analysis is the task of employing Machine Learning methods to the field of screenplays, movie scripts, and motion pictures to facilitate or enable vari- ous tasks throughout the entirety of a movie’s life-cycle. From helping with making informed decisions about a new movie script with respect to aspects such as its origi- nality, similarity to other movies, or even commercial viability, all the way to offering consumers new and interesting ways of viewing the final movie, many stages in the life-cycle of a movie stand to benefit from Machine Learning techniques that promise to reduce human effort, time, or both. -

THE ULTIMATE SUMMER HORROR MOVIES LIST Summertime Slashers, Et Al

THE ULTIMATE SUMMER HORROR MOVIES LIST Summertime Slashers, et al. Summer Camp Scares I Know What You Did Last Summer Friday the 13th I Still Know What You Did Last Summer Friday the 13th Part 2 All The Boys Love Mandy Lane Friday the 13th Part III The Texas Chain Saw Massacre (1974) Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (2003) Sleepaway Camp The Texas Chainsaw Massacre: The Beginning Sleepaway Camp II: Unhappy Campers House of Wax Sleepaway Camp III: Teenage Wasteland Wolf Creek The Final Girls Wolf Creek 2 Stage Fright Psycho Beach Party The Burning Club Dread Campfire Tales Disturbia Addams Family Values It Follows The Devil’s Rejects Creepy Cabins in the Woods Blood Beach Cabin Fever The Lost Boys The Cabin in the Woods Straw Dogs The Evil Dead The Town That Dreaded Sundown Evil Dead 2 VACATION NIGHTMARES IT Evil Dead Hostel Ghost Ship Tucker and Dale vs Evil Hostel: Part II From Dusk till Dawn The Hills Have Eyes Death Proof Eden Lake Jeepers Creepers Funny Games Turistas Long Weekend AQUATIC HORROR, SHARKS, & ANIMAL ATTACKS Donkey Punch Jaws An American Werewolf in London Jaws 2 An American Werewolf in Paris Jaws 3 Prey Joyride Jaws: The Revenge Burning Bright The Hitcher The Reef Anaconda Borderland The Shallows Anacondas: The Hunt for the Blood Orchid Tourist Trap 47 Meters Down Lake Placid I Spit On Your Grave Piranha Black Water Wrong Turn Piranha 3D Rogue The Green Inferno Piranha 3DD Backcountry The Descent Shark Night 3D Creature from the Black Lagoon Deliverance Bait 3D Jurassic Park High Tension Open Water The Lost World: Jurassic Park II Kalifornia Open Water 2: Adrift Jurassic Park III Open Water 3: Cage Dive Jurassic World Deep Blue Sea Dark Tide mrandmrshalloween.com. -

Click Here to Download The

FREE EXAM Complete Physical Exam Included New Clients Only Must present coupon. Offers cannot be combined 4 x 2” ad Wellness Plans Extended Hours Multiple Locations www.forevervets.com Your Community Voice for 50 Years PONTEYour Community Voice VED for 50 YearsRA RRecorecorPONTE VEDRA dderer entertainment EEXXTRATRA! ! Featuring TV listings, streaming information, sports schedules, puzzles and more! October 8 - 14, 2020 has a new home at THE LINKS! Other stars 1361 S. 13th Ave., Ste. 140 make music for Jacksonville Beach ‘GRAMMY Salute’ Offering: · Hydrafacials on PBS special · RF Microneedling · Body Contouring Jimmy Jam hosts “Great · B12 Complex / Performances: GRAMMY Lipolean Injections Salute to Music Legends” INSIDE: Sports listings, Friday on PBS. sports quiz and Get Skinny with it! player profile (904) 999-09771 x 5” ad Pages 18-19 www.SkinnyJax.com Now is a great time to It will provide your home: List Your Home for Sale • Complimentary coverage while the home is listed • An edge in the local market Kathleen Floryan LIST IT because buyers prefer to purchase a Broker Associate home that a seller stands behind • Reduced post-sale liability with [email protected] ListSecure® 904-687-5146 WITH ME! https://www.kathleenfloryan.exprealty.com BK3167010 I will provide you a FREE https://expressoffers.com/exp/kathleen-floryan America’s Preferred Ask me how to get cash offers on your home! Home Warranty for your home when we put it on the market. 4 x 3” ad BY JAY BOBBIN A new ‘GRAMMY Salute to Music Legends’ honors John What’s Available NOW On Prine, Chicago and others Each year, several music icons get a special their horn parts. -

Anes Murnane

•\ K, Volume 27, Number 7 Marist College, Poughkeepsle, N.Y. November 4,1982 J in anes by Joe Pared Petacchi despersed the crowd Marist freshman Kevin Eng, of residents that had gathered as 18, has been charged with word spread and finally per burglarizing the Sheahan Hall suaded Eng to come out. "He mailroom and stealing mail said the door was open and that containing cash and checks over he was just looking around," said the past two months, according to Petacchi. Detective - James McDowell, Eng and Petacchi talked in Town of Poughkeepsie police. Petacchi's room when, according Eng, who lived in the basement to Petacchi, Eng "took off when I of Sheahan, was arrested last told hirae to wait outside my Thursday'.'-'following the in room. I didn't want him in the vestigation of several complaints room when I called security." from Sheahan residents regarding After security notified missing mail. Police. have Poughkeepsie police of the in recovered about 100 pieces of cident, Petacchi and Jason mail and $300 in cash from a Hawkins, the freshman who first check Eng is accused of forging. heard somebody in the mailroom, /John Petacchi, resident were asked by McDowell to make assistant : on Sheahan second an official statement. floor, was downstairs Wednesday Eng was arrested the following doing laundry when Mark day. Cassano, Eng's roommate,, Eng is charged with third- approached him. "Mark was degree burglary, second-degree saying 'We got him, we got him. possession of stolen property and He's in the mailroom,' or second-degree forgery, all something to that effect," felonies, McDowell said. -

Gender Differences in Descriptions and Perceptions of Slasher Films

Sex Roles, Vol. 42, Nos. 1/2, 2000 Fear and Loathing at the Cineplex: Gender Differences in Descriptions and Perceptions of Slasher Films Justin M. Nolan1,2 and Gery W. Ryan1 University of Missouri This study investigates gender-specific descriptions and perceptions of slasher films. Sixty Euro-American university students (30 males and 30 females) were asked to recount in a written survey the details of the most memorable slasher film they remember watching and describe the emotional reactions evoked by that film. A text analysis approach was used to examine and interpret informant responses. Males recall a high percentage of descriptive images associated with what is called rural terror, a concept tied to fear of strangers and rural landscapes, whereas females display a greater fear of family terror, which includes themes of betrayed intimacy, stalkings, and spiritual possession. It is found that females report a higher level and a greater number of fear reactions than males, who report more anger and frustration responses. Gender-specific fears as personalized through slasher film recall are discussed with relation to socialization practices and power- control theory. The Texas Chainsaw Massacre scared me to death. It was intensely unpleasant, even though it’s a cheap splatter flick about some teenagers who get slaughtered by some deranged lunatics in rural Texas somewhere. I guess the most freaky thing about the movie is all the screaming. The one girl who barely escapes the chainsaw guy screams all throughout the movie. She is terrorized unrelentlessly, and after a series of close calls with the chainsaw she is finally rescued by a trucker. -

Proquest Dissertations

RECYCLED FEAR: THE CONTEMPORARY HORROR REMAKE AS AMERICAN CINEMA INDUSTRY STANDARD A Dissertation by JAMES FRANCIS, JR. Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UMI Number: 3430304 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMT Dissertation Publishing UMI 3430304 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Approved as to style and content by: ^aJftLtfv^ *3 tu.^r TrsAAO^p P, M&^< David Lavery Martha Hixon Chair of Committee Reader Cyt^-jCc^ C. U*-<?LC<^7 Wt^vA AJ^-i Linda Badley Tom Strawman Reader Department Chair (^odfrCtau/ Dr. Michael D. Allen Dean of Graduate Studies August 2010 Major Subject: English RECYCLED FEAR: THE CONTEMPORARY HORROR REMAKE AS AMERICAN CINEMA INDUSTRY STANDARD A Dissertation by JAMES FRANCIS, JR. Submitted to the Office of Graduate Studies of Middle Tennessee State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2010 Major Subject: English DEDICATION Completing this journey would not be possible without the love and support of my family and friends. -

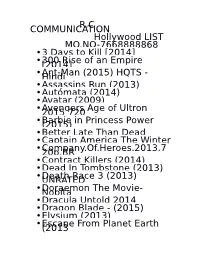

R.C COMMUNICATION Hollywood LIST MO.NO-7668888868 •3

COMMUNICATION R.C Hollywood LIST MO.NO-7668888868 •3 Days to Kill [2014] •[2014]300 Rise of an Empire •HindiAnt-Man (2015) HQTS - •Assassins Run (2013) •Autómata (2014) •Avatar (2009) •2015Avengers 720 Age of Ultron •(2015)Barbie in Princess Power •Better Late Than Dead •Captain America The Winter •20p.BRCompany.Of.Heroes.2013.7 •Contract Killers (2014) •Dead In Tombstone (2013) •UNRATEDDeath Race 3 (2013) •NobitaDoraemon The Movie- •Dracula Untold 2014 •Dragon Blade - (2015) •Elysium (2013) •(2013Escape From Planet Earth •Escape Plan (2013) •Evil Dead (2013) •(2014)Exodus Gods and Kings •Falcon Rising (2014) •Fantastic Four (2015) •Final Destination 2000 •Final Girl (2015) •Free Birds (2013) •Friday The 13th Part III 3D •Furious 7 2015 •Fury (2014) •Gangster Squad (2013) •TicketGolden Rules - Golden •Gravity (2013) •Grown Ups 2 (2013) •(2014)Guardians of the Galaxy •Gutshot Straight (2014) •HuntersHansel and Gretel Witch •Hercules (2014) •Hercules Reborn (2014 •Homefront (2013 •I Frankenstein (2014 •(2007)In The Name Of The King •Irumbu Kuthirai (2014) •(2014)Jack Ryan Shadow Recruit •Jack the Giant Slayer 2013 •(2014)Jarhead 2 Field of Fire •HuntersHansel and Gretel Witch •Hercules (2014) •Hercules Reborn (2014) •Homefront (2013) •I Frankenstein (2014) •I Frankenstein (2014) •I Frankenstein (2014) •I Frankenstein (2014) •Hercules (2014) •Homefront (2013) •I Frankenstein (2014) 720p •(2007)In The Name Of The King •Irumbu Kuthirai •(2014)Jack Ryan Shadow Recruit •Jack the Giant Slayer 2013 •(2014)Jarhead 2 Field of Fire •John Wick (2014) -

1. Needs to Have at Least Four Theatrically Released Films in the Series (Jaws I-III, Jaws: the Revenge)

Horror Franchise List Below you will find 24 franchises. Here is the criteria for the list. 1. Needs to have at least four theatrically released films in the series (Jaws I-III, Jaws: The Revenge). Compiling data on direct to DVD movies would be impossible because of lack of data/reviews/box office. Click here to see all the franchises. 2. I took sequels (Texas Chainsaw Massacre 2), remakes (The Texas Chainsaw Massacre) and prequels (Texas Chainsaw: the Beginning) into account. I also added the Romero Zombie franchise and the Hannibal films because they feature the same world, characters and cannibals. 3. Critical and audience data was collected from Rotten Tomatoes, IMDb and Amazon. Metacritic did not have enough data so we excluded it from the MFFM. 4. I am looking only at domestic box office and had to leave out several international series due to lack of data.The toughest omission was the [Rec] series. I Also had to leave out the Universal Monster films because there is a lack of consistent box-office data. Viva la Bride of Frankenstein though! 5. I added Alien vs. Predator and Alien vs. Predator Requiem to the Alien and Predator lists. It felt kinda obvious. Here are the franchises and films within them. Alien Alien, Aliens, Alien 3, Alien Resurrection, AVP, AVPR, Prometheus Amityville Horror Amityville Horror, Amityville Horror II, The Possession, Amityville 3D, Amityville Horror FInal Destination Final Destination, Final Destination 2, Final Destination 3, The Final Destination, Final Destination 5 Friday the 13th Friday the 13th, Friday the 13th: Part Two, Friday the 13th: Part III, Friday the 13th: The Final Chapter, Friday the 13th: A New Beginning, Friday the 13th: Part VI: Jason Lives, Friday the 13th: Part VII: The New Blood, Friday the 13th: Part VIII: Jason Takes Manhattan, Jason Goes to Hell: The FInal Friday, Jason X, Freddy vs. -

KILLING the SAD FAT GUY and the PREGNANT LADY: UNCOMFORTABLE DEATH in FRIDAY the 13TH PART III – 3D Wickham Clayton

KILLING THE SAD FAT GUY AND THE PREGNANT LADY: UNCOMFORTABLE DEATH IN FRIDAY THE 13TH PART III – 3D Wickham Clayton Co-creator and director, Sean S. Cunningham, describes Friday the 13th (1980) as “a roller- coaster ride, a funhouse sort of thing.”[i] It is artificial, visceral fun that spikes adrenalin, provides thrills, but doesn’t aspire to much in the way of intellectual engagement or emotional connection (beyond terror and horror) with characters or story. The success of the first film drove the development of the sequel. In Friday the 13th Part 2 (1981), director Steve Miner decided to embellish slightly without veering too far from the formula of the original. According to Miner, along with the other creators, he attempted to “improve upon some of the character and dialogue flaws [of Friday the 13th]. We attempted to make the characters a little more realistic. We did avoid ‘strip monopoly.’”[ii] Part 2 saw further success, so inevitably the producers began work on Friday the 13th Part III 3-D. “With the Friday the 13th films,” Miner declared, “we had always made a conscious decision to make the same movie over again, only each one would be slightly different. And I had always been intrigued with the concept of 3- D.”[iii] Miner, however, toyed with more changes than merely the use of 3-D: “I spent a lot of time developing a number of different storylines and approaches that would be a breakaway from the other films. Finally, we all decided that it would have been a mistake. -

Community Chest Spaces

Compilation of movies shown at Muncie Public Library from January 1, 2018 to present to fulfill Community Chest Spaces Attack of the Movie! Film series at Kennedy that showcases movies so bad they are good ● Faster, Pussycat! Kill! Kill! (1965) ● Xanadu (1980) ● True Stories (1986) ● Master of the Flying Guillotine ● The Deadly M antis (1957) (1976) ● I’m Gonna Git You Sucka (1988) ● Adventures of Baron Munchausen ● Ladies and Gentlemen, The (1988) Fabulous Stains (1982) ● Black Christmas (1974) ● Frankenstein Created Bikers (1967) ● Runaway (1984) ● Tom Waits: Big Time (1988) ● Hardware (1990) ● Pink Flamingos (1972) ● Bugsy Malone (1976) ● They Live (1988) ● Dark Side of the Rainbow (2000) ● Dead Alive (1992) ● The Lost Skeleton of Cadavra (2001) ************************************************************************************************************* Films of 1923 Film series at Kennedy that celebrated movies that entered the public domain ● Safety Last! (1923) ● Hunchback of Notre Dame (1923) ● The Ten Commandments (1923) ● Our Hospitality (1923) ************************************************************************************************************************ Horror Fest Horror film series at Kennedy held on every Friday the 13th each year ● Friday the 13th (1980) ● The Witch (2016) ● Friday the 13th Part II (1981) ● Society (1989) ● Friday the 13th Part III (1982) ● Cat People (1982) ● Creature from the Black Lagoon ● Horror of Dracula (1958) (1954) ● The Thing (1982) -

Fabricating Freddy Vs. Jason: Understanding a Motion Picture As a Social Encounter Between Fans and Filmmakers

Western Michigan University ScholarWorks at WMU Dissertations Graduate College 4-2007 Fabricating Freddy vs. Jason: Understanding a Motion Picture as a Social Encounter between Fans and Filmmakers Jason M. Rapelje Western Michigan University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations Part of the Film and Media Studies Commons, Social Psychology and Interaction Commons, and the Sociology of Culture Commons Recommended Citation Rapelje, Jason M., "Fabricating Freddy vs. Jason: Understanding a Motion Picture as a Social Encounter between Fans and Filmmakers" (2007). Dissertations. 910. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/910 This Dissertation-Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at ScholarWorks at WMU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at WMU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FABRICATING FREDDY VS. JASON: UNDERSTANDING A MOTION PICTURE AS A SOCIAL ENCOUNTER BETWEEN FANS AND FILMMAKERS by Jason M. Rapelje A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Graduate College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Sociology Dr. Paula S. Brush, Advisor Western Michigan University Kalamazoo, Michigan April 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. FABRICATING FREDDY VS JASON: UNDERSTANDING A MOTION PICTURE AS A SOCIAL ENCOUNTER BETWEEN FANS AND FILMMAKERS Jason M. Rapelje, Ph.D. Western Michigan University, 2007 The break in the mass communicative chain, which separates producers and receivers from one another in both time and space, impedes researchers from studying motion pictures as social encounters.