Canis Mesomelas – Black-Backed Jackal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Yellow Mongoose Cynictis Penicillata in the Great Fish River Reserve (Eastern Cape, South Africa)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by South East Academic Libraries System (SEALS) Spatio-temporal ecology of the yellow mongoose Cynictis penicillata in the Great Fish River Reserve (Eastern Cape, South Africa) By Owen Akhona Mbatyoti A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE (ZOOLOGY) in the Faculty of Science and Agriculture at the University of Fort Hare August 2012 Supervisor: Dr Emmanuel Do Linh San DECLARATION 1. This is to declare that this dissertation entitled “Spatio-temporal ecology of the yellow mongoose Cynictis penicillata in the Great Fish River Reserve (Eastern Cape, South Africa)” is my own work and has not been previously submitted to another institute. 2. I know that plagiarism means taking and using the ideas, writings, work or inventions of another person as if they were one’s own. I know that plagiarism not only includes verbatim copying, but also extensive use of another person’s ideas without proper acknowledgement (which sometimes includes the use of quotation marks). I know that plagiarism covers this sort of material found in textual sources (e.g. books, journal articles and scientific reports) and from the Internet. 3. I acknowledge and understand that plagiarism is wrong. 4. I understand that my research must be accurately referenced. I have followed the academic rules and conventions concerning referencing, citation and the use of quotations. 5. I have not allowed, nor will I in the future allow, anyone to copy my work with the intention of passing it off as their own work. -

Felis Silvestris, Wild Cat

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T60354712A50652361 Felis silvestris, Wild Cat Assessment by: Yamaguchi, N., Kitchener, A., Driscoll, C. & Nussberger, B. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Yamaguchi, N., Kitchener, A., Driscoll, C. & Nussberger, B. 2015. Felis silvestris. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T60354712A50652361. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T60354712A50652361.en Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; Microsoft; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; Wildscreen; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information -

Mammals of Jordan

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mammals of Jordan Z. AMR, M. ABU BAKER & L. RIFAI Abstract: A total of 78 species of mammals belonging to seven orders (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Carni- vora, Hyracoidea, Artiodactyla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia) have been recorded from Jordan. Bats and rodents represent the highest diversity of recorded species. Notes on systematics and ecology for the re- corded species were given. Key words: Mammals, Jordan, ecology, systematics, zoogeography, arid environment. Introduction In this account we list the surviving mammals of Jordan, including some reintro- The mammalian diversity of Jordan is duced species. remarkable considering its location at the meeting point of three different faunal ele- Table 1: Summary to the mammalian taxa occurring ments; the African, Oriental and Palaearc- in Jordan tic. This diversity is a combination of these Order No. of Families No. of Species elements in addition to the occurrence of Insectivora 2 5 few endemic forms. Jordan's location result- Chiroptera 8 24 ed in a huge faunal diversity compared to Carnivora 5 16 the surrounding countries. It shelters a huge Hyracoidea >1 1 assembly of mammals of different zoogeo- Artiodactyla 2 5 graphical affinities. Most remarkably, Jordan Lagomorpha 1 1 represents biogeographic boundaries for the Rodentia 7 26 extreme distribution limit of several African Total 26 78 (e.g. Procavia capensis and Rousettus aegypti- acus) and Palaearctic mammals (e. g. Eri- Order Insectivora naceus concolor, Sciurus anomalus, Apodemus Order Insectivora contains the most mystacinus, Lutra lutra and Meles meles). primitive placental mammals. A pointed snout and a small brain case characterises Our knowledge on the diversity and members of this order. -

Red List of Bangladesh Volume 2: Mammals

Red List of Bangladesh Volume 2: Mammals Lead Assessor Mohammed Mostafa Feeroz Technical Reviewer Md. Kamrul Hasan Chief Technical Reviewer Mohammad Ali Reza Khan Technical Assistants Selina Sultana Md. Ahsanul Islam Farzana Islam Tanvir Ahmed Shovon GIS Analyst Sanjoy Roy Technical Coordinator Mohammad Shahad Mahabub Chowdhury IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature Bangladesh Country Office 2015 i The designation of geographical entitles in this book and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature concerning the legal status of any country, territory, administration, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The biodiversity database and views expressed in this publication are not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, Bangladesh Forest Department and The World Bank. This publication has been made possible because of the funding received from The World Bank through Bangladesh Forest Department to implement the subproject entitled ‘Updating Species Red List of Bangladesh’ under the ‘Strengthening Regional Cooperation for Wildlife Protection (SRCWP)’ Project. Published by: IUCN Bangladesh Country Office Copyright: © 2015 Bangladesh Forest Department and IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holders, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holders. Citation: Of this volume IUCN Bangladesh. 2015. Red List of Bangladesh Volume 2: Mammals. IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh Country Office, Dhaka, Bangladesh, pp. -

Social Mongoose Vocal Communication: Insights Into the Emergence of Linguistic Combinatoriality

Zurich Open Repository and Archive University of Zurich Main Library Strickhofstrasse 39 CH-8057 Zurich www.zora.uzh.ch Year: 2017 Social Mongoose Vocal Communication: Insights into the Emergence of Linguistic Combinatoriality Collier, Katie Abstract: Duality of patterning, language’s ability to combine sounds on two levels, phonology and syntax, is considered one of human language’s defining features, yet relatively little is known about its origins. One way to investigate this is to take a comparative approach, contrasting combinatoriality in animal vocal communication systems with phonology and syntax in human language. In my the- sis, I took a comparative approach to the evolution of combinatoriality, carrying out both theoretical and empirical research. In the theoretical domain, I identified some prevalent misunderstandings in re- search on the emergence of combinatoriality that have propagated across disciplines. To address these misconceptions, I re-analysed existing examples of animal call combinations implementing insights from linguistics. Specifically, I showed that syntax-like combinations are more widespread in animal commu- nication than phonology-like sequences, which, combined with the absence of phonology in some human languages, suggested that syntax may have evolved before phonology. Building on this theoretical work, I empirically explored call combinations in two species of social mongooses. I first investigated social call combinations in meerkats (Suricata suricatta), demonstrating that call combinations represented a non-negligible component of the meerkat vocal communication system and could be used flexibly across various social contexts. Furthermore, I discussed a variety of mechanisms by which these combinations could be produced. Second, I considered call combinations in predation contexts. -

Follow-Up Visits to Alatash – Dinder Lion Conservation Unit Ethiopia

Follow-up visits to Alatash – Dinder Lion Conservation Unit Ethiopia & Sudan Hans Bauer, Ameer Awad, Eyob Sitotaw and Claudio Sillero-Zubiri 1-20 March 2017, Alatash National Park, Ethiopia 30 April - 16 May 2017, Dinder National Park, Sudan Report published in Oxford, September 2017 Wildlife Conservation Research Unit - University of Oxford (WildCRU); Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme (EWCP); Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority (EWCA); Mekele University (MU); Sudan Wildlife Research Centre (SWRC). Funded by the Born Free Foundation and Born Free USA. 1 Contents Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Teams ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Methods .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Area description - Alatash ....................................................................................................................... 6 Area description - Dinder ........................................................................................................................ 7 Results - Alatash ..................................................................................................................................... -

Glimpse of an African… Wolf? Cécile Bloch

$6.95 Glimpse of an African… Wolf ? PAGE 4 Saving the Red Wolf Through Partnerships PAGE 9 Are Gray Wolves Still Endangered? PAGE 14 Make Your Home Howl Members Save 10% Order today at shop.wolf.org or call 1-800-ELY-WOLF Your purchases help support the mission of the International Wolf Center. VOLUME 25, NO. 1 THE QUARTERLY PUBLICATION OF THE INTERNATIONAL WOLF CENTER SPRING 2015 4 Cécile Bloch 9 Jeremy Hooper 14 Don Gossett In the Long Shadow of The Red Wolf Species Survival Are Gray Wolves Still the Pyramids and Beyond: Plan: Saving the Red Wolf Endangered? Glimpse of an African…Wolf? Through Partnerships In December a federal judge ruled Geneticists have found that some In 1967 the number of red wolves that protections be reinstated for of Africa’s golden jackals are was rapidly declining, forcing those gray wolves in the Great Lakes members of the gray wolf lineage. remaining to breed with the more wolf population area, reversing Biologists are now asking: how abundant coyote or not to breed at all. the USFWS’s 2011 delisting many golden jackals across Africa The rate of hybridization between the decision that allowed states to are a subspecies known as the two species left little time to prevent manage wolves and implement African wolf? Are Africa’s golden red wolf genes from being completely harvest programs for recreational jackals, in fact, wolves? absorbed into the expanding coyote purposes. If biological security is population. The Red Wolf Recovery by Cheryl Lyn Dybas apparently not enough rationale for Program, working with many other conservation of the species, then the organizations, has created awareness challenge arises to properly express and laid a foundation for the future to the ecological value of the species. -

Pest Risk Assessment

PEST RISK ASSESSMENT Meerkat Suricata suricatta (Photo: Fir0002. Image from Wikimedia Commons under a GNU Free Documentation License, Version 1.2) March 2011 Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Resource Management and Conservation Division Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment 2011 Information in this publication may be reproduced provided that any extracts are acknowledged. This publication should be cited as: DPIPWE (2011) Pest Risk Assessment: Meerkat (Suricata suricatta). Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment. Hobart, Tasmania. About this Pest Risk Assessment This pest risk assessment is developed in accordance with the Policy and Procedures for the Import, Movement and Keeping of Vertebrate Wildlife in Tasmania (DPIPWE 2011). The policy and procedures set out conditions and restrictions for the importation of controlled animals pursuant to s32 of the Nature Conservation Act 2002. This pest risk assessment is prepared by DPIPWE for the use within the Department. For more information about this Pest Risk Assessment, please contact: Wildlife Management Branch Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment Address: GPO Box 44, Hobart, TAS. 7001, Australia. Phone: 1300 386 550 Email: [email protected] Visit: www.dpipwe.tas.gov.au Disclaimer The information provided in this Pest Risk Assessment is provided in good faith. The Crown, its officers, employees and agents do not accept liability however arising, including liability for negligence, for any loss resulting from the use of or reliance upon the information in this Pest Risk Assessment and/or reliance on its availability at any time. Pest Risk Assessment: Meerkat Suricata suricatta 2/22 1. -

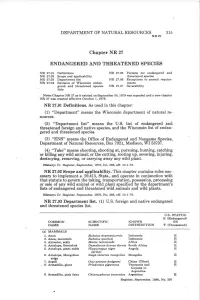

Endangered and Threatened Species

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 315 NR27 Chapter NR 27 ENDANGERED AND THREATENED SPECIES NR 27.01 Definitions NR 27 .05 Permits for endangered and NR 27.02 Scope end applicability threatened species NR 27.03 Department list NR 27 .06 Exceptions to permit require NR 27.04 Revision of Wisconsin endan ments gered and threatened species NR 27.07 Severability lists Note: Chapter NR 27 es it existed on September 30, 1979 was repealed and a new chapter NR 27 was created effective October 1, 1979. NR 27.01 Definitions. As used in this chapter: (1) "Department" means the Wisconsin department of natural re sources. (2) "Department list" means the U.S. list of endangered and threatened foreign and native species, and the Wisconsin list of endan gered and threatened species. (3) "ENS" means the Office of Endangered and Nongame Species, Department of Natural Resources, Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707. (4) "Take" means shooting, shooting at, pursuing, hunting, catching or killing any wild animal; or the cutting, rooting up, severing, injuring, destroying, removing, or carrying away any wild plant. Hlotory: Cr. Register, September, 1979, No. 285, eff. 10-1-79. NR 27.02 Scope and applicability. This chapter contains rules nec essary to implement s. 29.415, Stats., and operate in conjunction with that statute to govern the taking, transportation, possession, processing or sale of any wild animal or wild plant specified by the department's lists of endangered and threatened wild animals and wild plants. Hlotory: Cr. Register, September, 1979, No. 285, eff. 10-1-79. NR 27.03 Department list. -

The Role of Small Private Game Reserves in Leopard Panthera Pardus and Other Carnivore Conservation in South Africa

The role of small private game reserves in leopard Panthera pardus and other carnivore conservation in South Africa Tara J. Pirie Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of The University of Reading for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of Biological Sciences November 2016 Acknowledgements I would first like to thank my supervisors Professor Mark Fellowes and Dr Becky Thomas, without whom this thesis would not have been possible. I am sincerely grateful for their continued belief in the research and my ability and have appreciated all their guidance and support. I especially would like to thank Mark for accepting this project. I would like to acknowledge Will & Carol Fox, Alan, Lynsey & Ronnie Watson who invited me to join Ingwe Leopard Research and then aided and encouraged me to utilize the data for the PhD thesis. I would like to thank Andrew Harland for all his help and support for the research and bringing it to the attention of the University. I am very grateful to the directors of the Protecting African Wildlife Conservation Trust (PAWct) and On Track Safaris for their financial support and to the landowners and participants in the research for their acceptance of the research and assistance. I would also like to thank all the Ingwe Camera Club members; without their generosity this research would not have been possible to conduct and all the Ingwe Leopard Research volunteers and staff of Thaba Tholo Wilderness Reserve who helped to collect data and sort through countless images. To Becky Freeman, Joy Berry-Baker -

The Need to Address Black-Backed Jackal and Caracal Predation in South Africa

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Wildlife Damage Management Conferences -- Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center Proceedings for 2013 The Need to Address Black-backed Jackal and Caracal Predation in South Africa David L. Bergman United States Department of Agriculture, [email protected] HO De Waal University of the Free State Nico L. Avenant University of the Free State Michael J. Bodenchuk Texas Wildlife Services Program, [email protected] Michael C. Marlow United States Department of Agriculture See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_wdmconfproc Bergman, David L.; Waal, HO De; Avenant, Nico L.; Bodenchuk, Michael J.; Marlow, Michael C.; and Nolte, Dale L., "The Need to Address Black-backed Jackal and Caracal Predation in South Africa" (2013). Wildlife Damage Management Conferences -- Proceedings. 165. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/icwdm_wdmconfproc/165 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Wildlife Damage Management, Internet Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Wildlife Damage Management Conferences -- Proceedings by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors David L. Bergman, HO De Waal, Nico L. Avenant, Michael J. Bodenchuk, Michael C. Marlow, and Dale L. Nolte This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ icwdm_wdmconfproc/165 The Need to Address Black-backed Jackal and Caracal Predation in South Africa David L. Bergman United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service, Wildlife Services, Phoenix, Arizona HO De Waal Department of Animal Wildlife and Grassland Sciences, African Large Predator Research Unit, Universi- ty of the Free State, Bloemfontein, South Africa Nico L. -

Caracal Caracal – Caracal

Caracal caracal – Caracal Common names: Caracal, African Caracal, Asian Caracal, Desert Lynx (English), Rooikat, Lynx (Afrikaans), Indabutshe (Ndebele), Thwane (Setswana), Thooane, Thahalere (Sotho), Nandani (Tsonga), Thwani (Venda), Ingqawa, Ngada (Xhosa), Indabushe (Zulu) Taxonomic status: Species Taxonomic notes: The Caracal has been classified variously with Lynx and Felis in the past, but molecular evidence supports a monophyletic genus. It is closely allied with the African Golden Cat (Caracal aurata) and the Serval (Leptailurus serval), having diverged around 8.5 mya (Janczewski et al. 1995; Johnson & O’Brien 1997; Johnson et al. 2006). Seven subspecies have been recognised in Africa (Smithers 1975), of which two occur in southern Africa: C. c. damarensis from Namibia, the Northern Cape, southern Botswana and southern and central Angola; and the nominate C. c. caracal from the remainder of the species’ range in southern Africa (Meester et al. 1986). According to Stuart and Stuart (2013), however, these subspecies should best be considered as geographical variants. Assessment Rationale Caracals are widespread within the assessment region. They are considered highly adaptable and, within their distribution area, are found in virtually all habitats except the driest part of the Namib. They also tolerate high levels Marine Drouilly of human activity, and persist in most small stock areas in southern Africa, despite continuously high levels of Regional Red List status (2016) Least Concern persecution over many decades. In some regions it is National Red List status (2004) Least Concern even expected that Caracal numbers might have increased. Thus, the Least Concern listing remains. The Reasons for change No change use of blanket control measures over vast areas and the uncontrolled predation management efforts over virtually Global Red List status (2016) Least Concern the total assessment region are, however, of concern.