Leptailurus Serval, Serval

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Felis Silvestris, Wild Cat

The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ ISSN 2307-8235 (online) IUCN 2008: T60354712A50652361 Felis silvestris, Wild Cat Assessment by: Yamaguchi, N., Kitchener, A., Driscoll, C. & Nussberger, B. View on www.iucnredlist.org Citation: Yamaguchi, N., Kitchener, A., Driscoll, C. & Nussberger, B. 2015. Felis silvestris. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2015: e.T60354712A50652361. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-2.RLTS.T60354712A50652361.en Copyright: © 2015 International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale, reposting or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission from the copyright holder. For further details see Terms of Use. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species™ is produced and managed by the IUCN Global Species Programme, the IUCN Species Survival Commission (SSC) and The IUCN Red List Partnership. The IUCN Red List Partners are: BirdLife International; Botanic Gardens Conservation International; Conservation International; Microsoft; NatureServe; Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew; Sapienza University of Rome; Texas A&M University; Wildscreen; and Zoological Society of London. If you see any errors or have any questions or suggestions on what is shown in this document, please provide us with feedback so that we can correct or extend the information -

Mammals of Jordan

© Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Mammals of Jordan Z. AMR, M. ABU BAKER & L. RIFAI Abstract: A total of 78 species of mammals belonging to seven orders (Insectivora, Chiroptera, Carni- vora, Hyracoidea, Artiodactyla, Lagomorpha and Rodentia) have been recorded from Jordan. Bats and rodents represent the highest diversity of recorded species. Notes on systematics and ecology for the re- corded species were given. Key words: Mammals, Jordan, ecology, systematics, zoogeography, arid environment. Introduction In this account we list the surviving mammals of Jordan, including some reintro- The mammalian diversity of Jordan is duced species. remarkable considering its location at the meeting point of three different faunal ele- Table 1: Summary to the mammalian taxa occurring ments; the African, Oriental and Palaearc- in Jordan tic. This diversity is a combination of these Order No. of Families No. of Species elements in addition to the occurrence of Insectivora 2 5 few endemic forms. Jordan's location result- Chiroptera 8 24 ed in a huge faunal diversity compared to Carnivora 5 16 the surrounding countries. It shelters a huge Hyracoidea >1 1 assembly of mammals of different zoogeo- Artiodactyla 2 5 graphical affinities. Most remarkably, Jordan Lagomorpha 1 1 represents biogeographic boundaries for the Rodentia 7 26 extreme distribution limit of several African Total 26 78 (e.g. Procavia capensis and Rousettus aegypti- acus) and Palaearctic mammals (e. g. Eri- Order Insectivora naceus concolor, Sciurus anomalus, Apodemus Order Insectivora contains the most mystacinus, Lutra lutra and Meles meles). primitive placental mammals. A pointed snout and a small brain case characterises Our knowledge on the diversity and members of this order. -

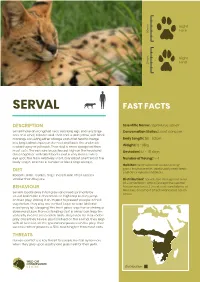

Serval Fact Sheet

Right 50mm Fore Right 50mm Hind SERVAL FAST FACTS DESCRIPTION Scientific Name: Leptailurus serval Servals have an elongated neck, very long legs, and very large Conversation Status: Least concern ears on a small, delicate skull. Their coat is pale yellow, with black markings consisting either of large spots that tend to merge Body Length: 59 - 92cm into longitudinal stripes on the neck and back. The underside is whitish grey or yellowish. Their skull is more elongated than Weight: 12 - 18kg most cats. The ears are broad based, high on the head and Gestation: 67 - 79 days close together, with black backs and a very distinct white eye spot. The tail is relatively short, only about one third of the Number of Young: 1 - 4 body length, and has a number of black rings along it. Habitat: Well-watered savanna long- grass environments, particularly reed beds DIET and other riparian habitats. Rodents, birds, reptiles, frogs, insects and other species smaller than they are. Distribution: Servals live throughout most of sub-Saharan Africa (except the central BEHAVIOUR African rainforest), the deserts and plains of Namibia, and most of Botswana and South Servals locate prey in tall grass and reeds primarily by Africa. sound and make a characteristic high leap as they jump on their prey, striking it on impact to prevent escape in thick vegetation. They also use vertical leaps to seize bird and insect prey by “clapping” the front paws together or striking a downward blow. From a standing start a serval can leap 3m vertically into the air to catch birds. -

1 the Origin and Evolution of the Domestic Cat

1 The Origin and Evolution of the Domestic Cat There are approximately 40 different species of the cat family, classification Felidae (Table 1.1), all of which are descended from a leopard-like predator Pseudaelurus that existed in South-east Asia around 11 million years ago (O’Brien and Johnson, 2007). Other than the domestic cat, the most well known of the Felidae are the big cats such as lions, tigers and panthers, sub-classification Panthera. But the cat family also includes a large number of small cats, including a group commonly known as the wildcats, sub-classification Felis silvestris (Table 1.2). Physical similarity suggests that the domestic cat (Felis silvestris catus) originally derived from one or more than one of these small wildcats. DNA examination shows that it is most closely related to the African wildcat (Felis silvestris lybica), which has almost identical DNA, indicating that the African wildcat is the domestic cat’s primary ancestor (Lipinski et al., 2008). The African Wildcat The African wildcat is still in existence today and is a solitary and highly territorial animal indigenous to areas of North Africa and the Near East, the region where domestication of the cat is believed to have first taken place (Driscoll et al., 2007; Faure and Kitchener, 2009). It is primarily a nocturnal hunter that preys mainly on rodents but it will also eat insects, reptiles and other mammals including the young of small antelopes. Also known as the Arabian or North African wildcat, it is similar in appearance to a domestic tabby, with a striped grey/sandy-coloured coat, but is slightly larger and with longer legs (Fig. -

Red List of Bangladesh Volume 2: Mammals

Red List of Bangladesh Volume 2: Mammals Lead Assessor Mohammed Mostafa Feeroz Technical Reviewer Md. Kamrul Hasan Chief Technical Reviewer Mohammad Ali Reza Khan Technical Assistants Selina Sultana Md. Ahsanul Islam Farzana Islam Tanvir Ahmed Shovon GIS Analyst Sanjoy Roy Technical Coordinator Mohammad Shahad Mahabub Chowdhury IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature Bangladesh Country Office 2015 i The designation of geographical entitles in this book and the presentation of the material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature concerning the legal status of any country, territory, administration, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. The biodiversity database and views expressed in this publication are not necessarily reflect those of IUCN, Bangladesh Forest Department and The World Bank. This publication has been made possible because of the funding received from The World Bank through Bangladesh Forest Department to implement the subproject entitled ‘Updating Species Red List of Bangladesh’ under the ‘Strengthening Regional Cooperation for Wildlife Protection (SRCWP)’ Project. Published by: IUCN Bangladesh Country Office Copyright: © 2015 Bangladesh Forest Department and IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non-commercial purposes is authorized without prior written permission from the copyright holders, provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction of this publication for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without prior written permission of the copyright holders. Citation: Of this volume IUCN Bangladesh. 2015. Red List of Bangladesh Volume 2: Mammals. IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh Country Office, Dhaka, Bangladesh, pp. -

Follow-Up Visits to Alatash – Dinder Lion Conservation Unit Ethiopia

Follow-up visits to Alatash – Dinder Lion Conservation Unit Ethiopia & Sudan Hans Bauer, Ameer Awad, Eyob Sitotaw and Claudio Sillero-Zubiri 1-20 March 2017, Alatash National Park, Ethiopia 30 April - 16 May 2017, Dinder National Park, Sudan Report published in Oxford, September 2017 Wildlife Conservation Research Unit - University of Oxford (WildCRU); Ethiopian Wolf Conservation Programme (EWCP); Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority (EWCA); Mekele University (MU); Sudan Wildlife Research Centre (SWRC). Funded by the Born Free Foundation and Born Free USA. 1 Contents Summary ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Teams ...................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 5 Methods .................................................................................................................................................. 5 Area description - Alatash ....................................................................................................................... 6 Area description - Dinder ........................................................................................................................ 7 Results - Alatash ..................................................................................................................................... -

Leptailurus Serval)

animals Article The Effect of Behind-The-Scenes Encounters and Interactive Presentations on the Welfare of Captive Servals (Leptailurus serval) Lydia K. Acaralp-Rehnberg 1,*, Grahame J. Coleman 1, Michael J. L. Magrath 2, Vicky Melfi 3, Kerry V. Fanson 4 and Ian M. Bland 1 1 Animal Welfare Science Centre, Faculty of Veterinary and Agricultural Sciences, University of Melbourne, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia; [email protected] (G.J.C.); [email protected] (I.M.B.) 2 Department of Wildlife Conservation and Science, Zoos Victoria, Parkville, Victoria 3052, Australia; [email protected] 3 Hartpury University, Gloucester GL193BE, UK; vicky.melfi@hartpury.ac.uk 4 Centre for Integrative Ecology, Deakin University, Geelong, Victoria 3216, Australia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +61-404-761-714 Received: 13 April 2020; Accepted: 15 April 2020; Published: 24 April 2020 Simple Summary: Live animal encounter programs are an increasingly popular occurrence in the modern zoo. The effects of such encounters on program animal welfare have not been studied extensively to date. The aim of this study was, therefore, to explore animal welfare effects associated with encounter programs in a small felid, the serval, which is commonly involved as a program animal in zoos. Specifically, this study investigated how serval behaviour and adrenocortical activity (level of faecal cortisol metabolites) were affected by short-term variations in encounter frequency. Over the course of the study, the frequency of encounters was manipulated so that servals alternated between four different treatments, involving interactive presentations, behind-the-scenes encounters, both activities combined, or no interaction at all. -

Savannah Cat’ ‘Savannah the Including Serval Hybrids Felis Catus (Domestic Cat), (Serval) and (Serval) Hybrids Of

Invasive animal risk assessment Biosecurity Queensland Agriculture Fisheries and Department of Serval hybrids Hybrids of Leptailurus serval (serval) and Felis catus (domestic cat), including the ‘savannah cat’ Anna Markula, Martin Hannan-Jones and Steve Csurhes First published 2009 Updated 2016 © State of Queensland, 2016. The Queensland Government supports and encourages the dissemination and exchange of its information. The copyright in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia (CC BY) licence. You must keep intact the copyright notice and attribute the State of Queensland as the source of the publication. Note: Some content in this publication may have different licence terms as indicated. For more information on this licence visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/ by/3.0/au/deed.en" http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au/deed.en Front cover: Close-up of a 4-month old F1 Savannah cat. Note the occelli on the back of the relaxed ears, and the tear-stain markings which run down the side of the nose. Photo: Jason Douglas. Image from Wikimedia Commons under a Public Domain Licence. Invasive animal risk assessment: Savannah cat Felis catus (hybrid of Leptailurus serval) 2 Contents Introduction 4 Identity of taxa under review 5 Identification of hybrids 8 Description 10 Biology 11 Life history 11 Savannah cat breed history 11 Behaviour 12 Diet 12 Predators and diseases 12 Legal status of serval hybrids including savannah cats (overseas) 13 Legal status of serval hybrids including savannah cats -

Status of the African Wild Dog in the Bénoué Complex, North Cameroon

Croes et al. African wild dogs in Cameroon Copyright © 2012 by the IUCN/SSC Canid Specialist Group. ISSN 1478-2677 Distribution Update Status of the African wild dog in the Bénoué Complex, North Cameroon 1* 2,3 1 1 Barbara Croes , Gregory Rasmussen , Ralph Buij and Hans de Iongh 1 Institute of Environmental Sciences (CML), University of Leiden, The Netherlands 2 Painted dog Conservation (PDC), Hwange National Park, Box 72, Dete, Zimbabwe 3 Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3PS, UK * Correspondence author Keywords: Lycaon pictus, North Cameroon, monitoring surveys, hunting concessions Abstract The status of the African wild dog Lycaon pictus in the West and Central African region is largely unknown. The vast areas of unspoiled Sudano-Guinean savanna and woodland habitat in the North Province of Cameroon provide a potential stronghold for this wide-ranging species. Nevertheless, the wild dog is facing numerous threats in this ar- ea, mainly caused by human encroachment and a lack of enforcement of laws and regulations in hunting conces- sions. Three years of surveys covering over 4,000km of spoor transects and more than 1,200 camera trap days, in addition to interviews with local stakeholders revealed that the African wild dog in North Cameroon can be consid- ered functionally extirpated. Presence of most other large carnivores is decreasing towards the edges of protected areas, while presence of leopard and spotted hyaena is negatively associated with the presence of villages. Lion numbers tend to be lower inside hunting concessions as compared to the national parks. -

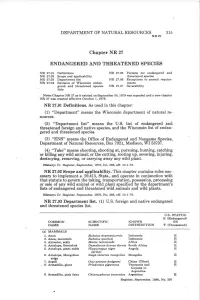

Endangered and Threatened Species

DEPARTMENT OF NATURAL RESOURCES 315 NR27 Chapter NR 27 ENDANGERED AND THREATENED SPECIES NR 27.01 Definitions NR 27 .05 Permits for endangered and NR 27.02 Scope end applicability threatened species NR 27.03 Department list NR 27 .06 Exceptions to permit require NR 27.04 Revision of Wisconsin endan ments gered and threatened species NR 27.07 Severability lists Note: Chapter NR 27 es it existed on September 30, 1979 was repealed and a new chapter NR 27 was created effective October 1, 1979. NR 27.01 Definitions. As used in this chapter: (1) "Department" means the Wisconsin department of natural re sources. (2) "Department list" means the U.S. list of endangered and threatened foreign and native species, and the Wisconsin list of endan gered and threatened species. (3) "ENS" means the Office of Endangered and Nongame Species, Department of Natural Resources, Box 7921, Madison, WI 53707. (4) "Take" means shooting, shooting at, pursuing, hunting, catching or killing any wild animal; or the cutting, rooting up, severing, injuring, destroying, removing, or carrying away any wild plant. Hlotory: Cr. Register, September, 1979, No. 285, eff. 10-1-79. NR 27.02 Scope and applicability. This chapter contains rules nec essary to implement s. 29.415, Stats., and operate in conjunction with that statute to govern the taking, transportation, possession, processing or sale of any wild animal or wild plant specified by the department's lists of endangered and threatened wild animals and wild plants. Hlotory: Cr. Register, September, 1979, No. 285, eff. 10-1-79. NR 27.03 Department list. -

Hybrid Cats’ Position Statement, Hybrid Cats Dated January 2010

NEWS & VIEWS AAFP Position Statement This Position Statement by the AAFP supersedes the AAFP’s earlier ‘Hybrid cats’ Position Statement, Hybrid cats dated January 2010. The American Association of Feline Practitioners (AAFP) strongly opposes the breeding of non-domestic cats to domestic cats and discourages ownership of early generation hybrid cats, due to concerns for public safety and animal welfare issues. Unnatural breeding between intended mates can make The AAFP strongly opposes breeding difficult. the unnatural breeding of non- Domestic cats have 38 domestic to domestic cats. This chromosomes, and most commonly includes both natural breeding bred non-domestic cats have 36 and artificial insemination. chromosomes. This chromosomal The AAFP opposes the discrepancy leads to difficulties unlicensed ownership of non- in producing live births. Gestation domestic cats (see AAFP’s periods often differ, so those ‘Ownership of non-domestic felids’ kittens may be born premature statement at catvets.com). The and undersized, if they even AAFP recognizes that the offspring survive. A domestic cat foster of cats bred between domestic mother is sometimes required cats and non-domestic (wild) cats to rear hybrid kittens because are gaining in popularity due to wild females may reject premature their novelty and beauty. or undersized kittens. Early There are two commonly seen generation males are usually hybrid cats. The Bengal (Figure 1), sterile, as are some females. with its spotted coat, is perhaps The first generation (F1) female the most popular hybrid, having its offspring of a domestic cat bred to origins in the 1960s. The Bengal a wild cat must then be mated back is a cross between the domestic to a domestic male (producing F2), cat and the Asian Leopard Cat. -

Flat Headed Cat Andean Mountain Cat Discover the World's 33 Small

Meet the Small Cats Discover the world’s 33 small cat species, found on 5 of the globe’s 7 continents. AMERICAS Weight Diet AFRICA Weight Diet 4kg; 8 lbs Andean Mountain Cat African Golden Cat 6-16 kg; 13-35 lbs Leopardus jacobita (single male) Caracal aurata Bobcat 4-18 kg; 9-39 lbs African Wildcat 2-7 kg; 4-15 lbs Lynx rufus Felis lybica Canadian Lynx 5-17 kg; 11-37 lbs Black Footed Cat 1-2 kg; 2-4 lbs Lynx canadensis Felis nigripes Georoys' Cat 3-7 kg; 7-15 lbs Caracal 7-26 kg; 16-57 lbs Leopardus georoyi Caracal caracal Güiña 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Sand Cat 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Leopardus guigna Felis margarita Jaguarundi 4-7 kg; 9-15 lbs Serval 6-18 kg; 13-39 lbs Herpailurus yagouaroundi Leptailurus serval Margay 3-4 kg; 7-9 lbs Leopardus wiedii EUROPE Weight Diet Ocelot 7-18 kg; 16-39 lbs Leopardus pardalis Eurasian Lynx 13-29 kg; 29-64 lbs Lynx lynx Oncilla 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Leopardus tigrinus European Wildcat 2-7 kg; 4-15 lbs Felis silvestris Pampas Cat 2-3 kg; 4-6 lbs Leopardus colocola Iberian Lynx 9-15 kg; 20-33 lbs Lynx pardinus Southern Tigrina 1-3 kg; 2-6 lbs Leopardus guttulus ASIA Weight Diet Weight Diet Asian Golden Cat 9-15 kg; 20-33 lbs Leopard Cat 1-7 kg; 2-15 lbs Catopuma temminckii Prionailurus bengalensis 2 kg; 4 lbs Bornean Bay Cat Marbled Cat 3-5 kg; 7-11 lbs Pardofelis badia (emaciated female) Pardofelis marmorata Chinese Mountain Cat 7-9 kg; 16-19 lbs Pallas's Cat 3-5 kg; 7-11 lbs Felis bieti Otocolobus manul Fishing Cat 6-16 kg; 14-35 lbs Rusty-Spotted Cat 1-2 kg; 2-4 lbs Prionailurus viverrinus Prionailurus rubiginosus Flat