Directing Molière: Presenting the French

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jean Giraudoux'

AUDIENCE GUIDE A NOISE WITHIN PRESENTS Jean Giraudoux’ Translation by Maurice Valency Photo of Deborah Strang by Tim Neighbors TABLE OF CONTENTS Characters ....................................................3 Synopsis .....................................................4 About the Playwright: Jean Giraudoux .............................5 Timeline of Giraudoux’s Life and Works ............................6 Historical Context: Paris, 1940-1944 ...............................7 Geographical Context: Where is Chaillot? ...........................9 Giraudoux’s Style .............................................10 The Play as Political Satire ......................................11 The Importance of Trial Scenes ..................................12 Why Trial Scenes Work in Theatre ................................13 Themes .....................................................14 Glossaries: Life in France .............................................15 Business Jargon ...........................................16 Does Life Imitate Art? UCI Production of The Madwoman of Chaillot circa 1969 .............17 Drawing Connections: Madwoman Themes in US Politics .............18 Additional Resources ..........................................20 Let us presume that under a Parisian district there is a rich oil well. Accordingly, conspirators from large corporations, treasure hunters and all kinds of profiteers plan a secret action. One woman, the loved Aurelie and better known as the Madwoman of Chaillot decides to take a stand against demolition, plunder -

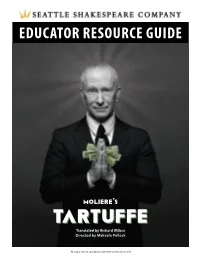

Translated by Richard Wilbur Directed by Makaela Pollock

Translated by Richard Wilbur Directed by Makaela Pollock All original material copyright © Seattle Shakespeare Company 2015 WELCOME Dear Educators, Tartuffe is a wonderful play, and can be great for students. Its major themes of hypocrisy and gullibility provide excellent prompts for good in-class discussions. Who are the “Tartuffes” in our 21st century world? What can you do to avoid being fooled the way Orgon was? Tartuffe also has some challenges that are best to discuss with students ahead of time. Its portrayal of religion as the source of Tartuffe’s hypocrisy angered priests and the deeply religious when it was first written, which led to the play being banned for years. For his part, Molière always said that the purpose of Tartuffe was not to lampoon religion, but to show how hypocrisy comes in many forms, and people should beware of religious hypocrisy among others. There is also a challenging scene between Tartuffe and Elmire at the climax of the play (and the end of Orgon’s acceptance of Tartuffe). When Tartuffe attempts to seduce Elmire, it is up to the director as to how far he gets in his amorous attempts, and in our production he gets pretty far! This can also provide an excellent opportunity to talk with students about staunch “family values” politicians who are revealed to have had affairs, the safety of women in today’s society, and even sexual assault, depending on the age of the students. Molière’s satire still rings true today, and shows how some societal problems have not been solved, but have simply evolved into today’s context. -

Download Teachers' Notes

Teachers’ Notes Researched and Compiled by Michele Chigwidden Teacher’s Notes Adelaide Festival Centre has contributed to the development and publication of these teachers’ notes through its education program, CentrED. Brink Productions’ by Molière A new adaptation by Paul Galloway Directed by Chris Drummond INTRODUCTION Le Malade imaginaire or The Hypochondriac by French playwright Molière, was written in 1673. Today Molière is considered one of the greatest masters of comedy in Western literature and his work influences comedians and dramatists the world over1. This play is set in the home of Argan, a wealthy hypochondriac, who is as obsessed with his bowel movements as he is with his mounting medical bills. Argan arranges for Angélique, his daughter, to marry his doctor’s nephew to get free medical care. The problem is that Angélique has fallen in love with someone else. Meanwhile Argan’s wife Béline (Angélique’s step mother) is after Argan’s money, while their maid Toinette is playing havoc with everyone’s plans in an effort to make it all right. Molière’s timeless satirical comedy lampoons the foibles of people who will do anything to escape their fear of mortality; the hysterical leaps of faith and self-delusion that, ironically, make us so susceptible to the quackery that remains apparent today. Brink’s adaptation, by Paul Galloway, makes Molière’s comedy even more accessible, and together with Chris Drummond’s direction, the brilliant ensemble cast and design team, creates a playful immediacy for contemporary audiences. These teachers’ notes will provide information on Brink Productions along with background notes on the creative team, cast and a synopsis of The Hypochondriac. -

Moliere-The Miser-Synopsis.Pdf

Thompson, The Miser 5 Introducing to you a masterpiece by one of the 17th Century's most talented playwrights... Jean-Baptiste Moliere.... Summary of the Plot Harpagon, a rich miser, rules his house with a meanness which the talk of the town. He keeps his horses so weak that they cannot be used. He lends money at such an extornionate rate that the borrower will be crippled by it and he is constantly in fear of having his wealth stolen from under his nose. Obsessively fearful, he suspects everyone and constantly checks his grounds where he has buried a large sum of money to keep it safe! As for the real treasures, his children, he marginalises and dominates them. He deprives them of independence by denying them money. He deprives them of the freedom to choose a marriage partner for themselves. Instead, he uses them the gain more riches for himself by organising wealthy spouses for them. As if this isn't enough he is, hypocritically, planning to marry for lust. Since father and son have designs on the same woman, they become rivals in love. But such is the force of true love that through a staged robbery the children take control of their own destinies forcing their father to give up his plans for their weddings in return for the restoration of his wealth. And en route they discover one or two surprises about themselves that they could not have begun to imagine. The Play In Context L'avare (The Miser) was written in 1668, after a difficult period for Moliere personally. -

Jacques Copeau Jacques Copeau: Dramatic Critic and Reformer of the Theatre

JACQUES COPEAU JACQUES COPEAU: DRAMATIC CRITIC AND REFORMER OF THE THEATRE By WILLIAM THOMAS MASON A Thesis Submitted to the 2'aculty of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Hequlrements for the Degree lViaster of Arts McMaster University October 1973 MASTER OF ARTS (1973) McMASTER UNIVERSITY (French) Hamilton, Ontario. TITLE: Jacques Copeau: Dramatic Critic and Reformer of the Theatre AUTHOR: William Thomas Mason, B.A. (McMaster University) M.A. (Johns Hopkins University) SUPERVISOR: Professor B. S. Pocknell PAGES: v, 83 SCOPE AND CONTENTS: An analysis of the development of Jacques Copeau's principles of dramatic art, of their anplica tian ta a renovation of .J.:'rench theatre and of their influence on succeeding theatrical figures -' (ii) Acknowledgements My thanks to Dr. Brian S. Pocknell for hie interest, encouragement and counsel and to McMaster University for its financial assistance. (iii) Table of Contents Introduction: Copeau's career 1 Copeau the cri tic 16 Copeau the reformer 36 Copeau's legacy 61 Appendix: Repertory of the Vieux-Colombier 73 Select Bibliogranhy 76 (iv) Abbreviations ~. Jacques Copeau, So~irs du Vieux-Colombier. C.R.B. Cahiers de la Comnagnie Madeleine Renaud -- Jean-Louis --~- ~-- -----Barraul t. ---R.H.T. Re~Je d'Histoire du Théâtre. (v) I. Introduction: Copeau's career Jacques Copeau's career in the theatre from his days as dramatic critic, "when many of his principles developed, through his years of practical reform as director of the Ihéâtre du Vieux=folombier, to the propagation of his ideals by his former actors and students or by admirers has had such a profound influence on the art of the theatre that he can be ranked with Max Reinhardt in Germany, Adolphe Appia in Switz- erland, Edward Gordon Craig in England and Constantin ~tanis- lavsky in Russia as one of the outstanding leaders in early twentieth-century theatre. -

The Plays of Moliere Viewed As Commentary on Women and Their Place in Society

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Master's Theses Theses and Dissertations 1943 The Plays of Moliere Viewed as Commentary on Women and Their Place in Society Helen A. Jones Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses Part of the French and Francophone Literature Commons Recommended Citation Jones, Helen A., "The Plays of Moliere Viewed as Commentary on Women and Their Place in Society" (1943). Master's Theses. 631. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_theses/631 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 1943 Helen A. Jones OO:MMENTARY ON WOlIEN.. .AND THEIB PLACE IN SOOlEY BELEN A. JONES I .. OF TfIE 11lQUIRlUtENTS :roR THE DlfGRD OF M.AS.rER OF ARTS IN LOYOLA. UNIVERSITY ... october 1943 TABlE OF CONT1m!B Page INTRODUCTION • • • • • • • • • 111 Chapter • I. MOLIERE AND HIS TIMES • • • • • 1 II. RIGHTS OF WOMEN • • • • • • 16 III. SOCIAL flESPONSIBILITIES OF WOJ/lEN • • 35 IV. CRITICAL DISCUSSION • • • • • 54 v. CONCLUSION • • • • • • • 66 BIBLIOGRAPRY • • • • • • • • • 68 ; .. INl'BODUCTION The purpose ot this paper is to consider views on rights and re- sponsibilit1es ot wceen as revealed in the'comedies ot Moliere. In dis- ...., cussing these Views, the writer will attempt to show that, on the Whole, these plays present a unitied, consistent body ot commentary on women and their place in society. -

The Misanthrope, Tartuffe, and Other Plays Free

FREE THE MISANTHROPE, TARTUFFE, AND OTHER PLAYS PDF Moliere,Maya Slater | 400 pages | 15 Jul 2008 | Oxford University Press | 9780199540181 | English | Oxford, United Kingdom The Misanthrope: Study Guide | SparkNotes The play satirizes the hypocrisies of French aristocratic society, but it also engages a more serious tone when pointing out the flaws that all humans possess. As a result, Tartuffe is much uncertainty about whether the main character, Alceste, is supposed to be perceived as Tartuffe hero for his strong standards of honesty or whether and Other Plays is supposed to be perceived as a fool for having such idealistic and unrealistic views about society. He believed that the audience should be supporting Alceste and his views about society rather than disregarding his idealistic notions and belittling him as a character. Much to the horror of Tartuffe friends and companions, Alceste rejects la politessethe social conventions of the seventeenth- century French ruelles later called salons in the The Misanthrope century. His deep The Misanthrope for her primarily serve to counter his negative expressions The Misanthrope mankind, since the fact that he has such feelings includes him amongst those he so fiercely criticizes. When Alceste insults a sonnet written by the powerful noble Oronte, he is called to stand trial. Refusing to dole out false compliments, he is charged and humiliated, and resolves on self-imposed exile. She has written identical love letters to numerous suitors including to Oronte and broken her vow to favor him above all others. He gives her an ultimatum: he will forgive Tartuffe and marry her if she runs away with him to exile. -

The Work of the Little Theatres

TABLE OF CONTENTS PART THREE PAGE Dramatic Contests.144 I. Play Tournaments.144 1. Little Theatre Groups .... 149 Conditions Eavoring the Rise of Tournaments.150 How Expenses Are Met . -153 Qualifications of Competing Groups 156 Arranging the Tournament Pro¬ gram 157 Setting the Tournament Stage 160 Persons Who J udge . 163 Methods of Judging . 164 The Prizes . 167 Social Features . 170 2. College Dramatic Societies 172 3. High School Clubs and Classes 174 Florida University Extension Con¬ tests .... 175 Southern College, Lakeland, Florida 178 Northeast Missouri State Teachers College.179 New York University . .179 Williams School, Ithaca, New York 179 University of North Dakota . .180 Pawtucket High School . .180 4. Miscellaneous Non-Dramatic Asso¬ ciations .181 New York Community Dramatics Contests.181 New Jersey Federation of Women’s Clubs.185 Dramatic Work Suitable for Chil¬ dren .187 4 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE II. Play-Writing Contests . 188 1. Little Theatre Groups . 189 2. Universities and Colleges . I9I 3. Miscellaneous Groups . • 194 PART FOUR Selected Bibliography for Amateur Workers IN THE Drama.196 General.196 Production.197 Stagecraft: Settings, Lighting, and so forth . 199 Costuming.201 Make-up.203 Acting.204 Playwriting.205 Puppetry and Pantomime.205 School Dramatics. 207 Religious Dramatics.208 Addresses OF Publishers.210 Index OF Authors.214 5 LIST OF TABLES PAGE 1. Distribution of 789 Little Theatre Groups Listed in the Billboard of the Drama Magazine from October, 1925 through May, 1929, by Type of Organization . 22 2. Distribution by States of 1,000 Little Theatre Groups Listed in the Billboard from October, 1925 through June, 1931.25 3. -

Elvire Jouvet 40 07/07/2016

Elvire Jouvet 40 07/07/2016 Elvire Jouvet 40 Brigitte Jaques Mise en scène Stéphane Laudier dispositif scénique Stéphane Laudier costumes Maud Adelen lumières Christophe Mazet avec Jean Marc Bourg Distribution en cours… Production Compagnie V-2 Schneider (durée sous réserve 1h10) Création 2017-2018 Elvire Jouvet 40 07/07/2016 Argument Au Conservatoire d’Art dramatique de Paris, à raison de sept séances qui ont lieu entre le 14 février et le 21 septembre 1940, Louis Jouvet fait travailler à une jeune actrice, Claudia, la dernière scène d’Elvire (acte IV, scène 6) du Dom Juan de Molière. Claudia répète chaque fois la scène devant la classe assemblée, qui intervient de temps à autre sous l’impulsion du Maître. Parmi tous les cours publiés, la singularité des sept leçons à Claudia vient de ce qu’on assiste à l’initiation finale d’une élève parvenue au terme de son apprentissage, laquelle a lieu dans cette scène de Dom Juan à l’épreuve d’un des sommets de l’art théâtral. Au sujet de Elvire Jouvet 40 Une mise en scène est un aveu, disait Jouvet, et c’est bien à la déclaration d’un aveu que ces leçons nous font assister. Elles semblent en effet, à mesure que l’on s’achemine vers la fin, les stations marquées d’une approche de l’art théâtral, comme d’un « phénomène de chimie céleste » Jouvet veut Claudia comme Elvire : extatique, inconsciente, égarée, et même anorexique, dans un « état de viduité » tel que l’actrice devienne pure transparence, pure voix qui jaillit entre le texte et le monde, pure interprète. -

Jacques Weber : « La Sensation De Parfaire Mon Métier »

Jacques Weber : « La sensation de parfaire mon métier » http://abonnes.lemonde.fr/scenes/article/2016/11/03/jacques-weber-la-... Jacques Weber : « La sensation de parfaire mon métier » Le comédien, qui joue dans « Le Temps et la Chambre », de Botho Strauss, dit aborder ses rôles de manière « apaisée ». LE MONDE | 03.11.2016 à 08h26 • Mis à jour le 03.11.2016 à 13h07 | Propos recueillis par Brigitte Salino (/journaliste/brigitte- salino/) 1 sur 3 07/11/2016 11:08 Jacques Weber : « La sensation de parfaire mon métier » http://abonnes.lemonde.fr/scenes/article/2016/11/03/jacques-weber-la-... Jacques Weber. MARCO CASTRO POUR « LE MONDE » Jacques Weber a bâti sa carrière en jouant des premiers rôles, Cyrano, Alceste, Tartuffe ou Dom Juan, dans des spectacles qui reposaient sur lui. Il a aussi dirigé deux centres dramatiques nationaux, à Lyon, de 1979 à 1985, puis à Nice, de 1986 à 2001. Depuis quelques années, il privilégie le travail avec de grands metteurs en scène. Après Peter Stein – qui l’a dirigé en 2013 dans Le Prix Martin, d’Eugène Labiche, à l’Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe, et ce printemps dans La Dernière Bande, de Samuel Beckett, à l’Œuvre –, il joue, sous la direction d’Alain Françon, Le Temps et la Chambre, de Botho Strauss, créé au Théâtre national de Strasbourg, avant de partir en tournée. Dans cette pièce chorale, Jacques Weber se glisse au milieu d’une distribution magnifique, qui réunit en particulier Dominique Valadié, Georgia Scalliet, Wladimir Yordanoff et Gilles Privat. Retour sur le trajet d’un comédien qui peu à peu quitte ses habits de héros. -

Archives Louis Jouvet Conservées À La Société D’Histoire Du Théâtre

Archives Louis Jouvet Conservées à la Société d’histoire du théâtre Boîte Paris Q - R : Chemise « Jean-Paul Jouvet » - Lettres de Jean-Paul Jouvet ou à Jean-Paul Jouvet - 1 carte postale de J.P. Jouvet à L. Chancerel - 1 carte de remerciement - Lettres de Léon Chancerel à Madame Jouvet et Gustave Jouvet Chemise « Lettres diverses de Louis Jouvet » - Lettres de Louis Jouvet ou à Louis Jouvet (à L. Chancerel en général) - 1 Carte postale de Louis Jouvet à L. Chancerel - 1 Carte postale de Lisa à L. Chancerel - 1 Carte de Louis Jouvet à Léon Chancerel - 1 Carte de vœux à « Vovonne » de Louis Jouvet - Lettres adressées à Sébastien (Léon Chancerel) - Lettres de Louis Jouvet à Pierre Renoir - Lettre de Max Fischer à L. Jouvet - Lettre de L. Jouvet à J. Sarment - Lettre de L. Jouvet à Mr. Rouché - Lettre autographe de Louis Jouvet Chemise « Square, semaine L. Jouvet. La société des amis de Louis Jouvet » - 2 cartes d’invitations pour l’inauguration du square de l’Opéra-Louis-Jouvet (6 mai 1955) - 1 carte d’invitation pour l’inauguration d’une plaque en mémoire de Louis Jouet (4 déc. 1952), théâtre de l’Athénée. - Coupures de presses sur ces inaugurations - 4 coupures de presse sur La Société des amis de Louis Jouvet - 1 Liste d’adresse, et brouillon. Chemise « Lettres N° Jouvet » : - 1 carte de visite d’Henri Legrand, datant de 1952, avec mot manuscrit - 1 carte de visite de René Bastien, avec mot manuscrit - 1 carte postale de Pauline et ? à Léon Chancerel Inventaire archives Louis Jouvet, Société d’histoire du théâtre. -

The Theatre of Death: the Uncanny in Mimesis Tadeusz Kantor, Aby Warburg, and an Iconography of the Actor; Or, Must One Die to Be Dead

The Theatre of Death: The Uncanny in Mimesis Tadeusz Kantor, Aby Warburg, and an Iconography of the Actor; Or, must one die to be dead. Twitchin, Mischa The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without the prior written consent of the author For additional information about this publication click this link. http://qmro.qmul.ac.uk/jspui/handle/123456789/8626 Information about this research object was correct at the time of download; we occasionally make corrections to records, please therefore check the published record when citing. For more information contact [email protected] The Theatre of Death: The Uncanny in Mimesis Tadeusz Kantor, Aby Warburg, and an Iconography of the Actor; Or, must one die to be dead? Mischa Twitchin Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy. 1 The Theatre of Death: the Uncanny in Mimesis (Abstract) The aim of this thesis is to explore an heuristic analogy as proposed in its very title: how does a concept of the “uncanny in mimesis” and of the “theatre of death” give content to each other – historically and theoretically – as distinct from the one providing either a description of, or even a metaphor for, the other? Thus, while the title for this concept of theatre derives from an eponymous manifesto of Tadeusz Kantor’s, the thesis does not aim to explain what the concept might mean in this historically specific instance only. Rather, it aims to develop a comparative analysis, through the question of mimesis, allowing for different theatre artists to be related within what will be proposed as a “minor” tradition of modernist art theatre (that “of death”).