255 Subsistence , Settlement , Ande Nvironment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Marais Des Cygnes River Basin Total Maximum Daily Load

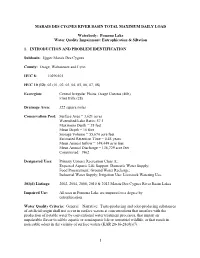

MARAIS DES CYGNES RIVER BASIN TOTAL MAXIMUM DAILY LOAD Waterbody: Pomona Lake Water Quality Impairment: Eutrophication & Siltation 1. INTRODUCTION AND PROBLEM IDENTIFICATION Subbasin: Upper Marais Des Cygnes County: Osage, Wabaunsee and Lyon HUC 8: 10290101 HUC 10 (12): 02 (01, 02, 03, 04, 05, 06, 07, 08) Ecoregion: Central Irregular Plains, Osage Cuestas (40b) Flint Hills (28) Drainage Area: 322 square miles Conservation Pool: Surface Area = 3,621 acres Watershed/Lake Ratio: 57:1 Maximum Depth = 38 feet Mean Depth = 16 feet Storage Volume = 55,670 acre feet Estimated Retention Time = 0.45 years Mean Annual Inflow = 149,449 acre feet Mean Annual Discharge = 136,729 acre feet Constructed: 1962 Designated Uses: Primary Contact Recreation Class A; Expected Aquatic Life Support; Domestic Water Supply; Food Procurement; Ground Water Recharge; Industrial Water Supply; Irrigation Use; Livestock Watering Use. 303(d) Listings: 2002, 2004, 2008, 2010 & 2012 Marais Des Cygnes River Basin Lakes Impaired Use: All uses in Pomona Lake are impaired to a degree by eutrophication Water Quality Criteria: General – Narrative: Taste-producing and odor-producing substances of artificial origin shall not occur in surface waters at concentrations that interfere with the production of potable water by conventional water treatment processes, that impart an unpalatable flavor to edible aquatic or semiaquatic life or terrestrial wildlife, or that result in noticeable odors in the vicinity of surface waters (KAR 28-16-28e(b)(7). 1 Nutrients - Narrative: The introduction of plant nutrients into streams, lakes, or wetlands from artificial sources shall be controlled to prevent the accelerated succession or replacement of aquatic biota or the production of undesirable quantities or kinds of aquatic life (KAR 28-16- 28e(c)(2)(A)). -

Sediment Transport in the San Francisco Bay Coastal System: an Overview

Marine Geology 345 (2013) 3–17 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Geology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/margeo Sediment transport in the San Francisco Bay Coastal System: An overview Patrick L. Barnard a,⁎, David H. Schoellhamer b,c, Bruce E. Jaffe a, Lester J. McKee d a U.S. Geological Survey, Pacific Coastal and Marine Science Center, Santa Cruz, CA, USA b U.S. Geological Survey, California Water Science Center, Sacramento, CA, USA c University of California, Davis, USA d San Francisco Estuary Institute, Richmond, CA, USA article info abstract Article history: The papers in this special issue feature state-of-the-art approaches to understanding the physical processes Received 29 March 2012 related to sediment transport and geomorphology of complex coastal–estuarine systems. Here we focus on Received in revised form 9 April 2013 the San Francisco Bay Coastal System, extending from the lower San Joaquin–Sacramento Delta, through the Accepted 13 April 2013 Bay, and along the adjacent outer Pacific Coast. San Francisco Bay is an urbanized estuary that is impacted by Available online 20 April 2013 numerous anthropogenic activities common to many large estuaries, including a mining legacy, channel dredging, aggregate mining, reservoirs, freshwater diversion, watershed modifications, urban run-off, ship traffic, exotic Keywords: sediment transport species introductions, land reclamation, and wetland restoration. The Golden Gate strait is the sole inlet 9 3 estuaries connecting the Bay to the Pacific Ocean, and serves as the conduit for a tidal flow of ~8 × 10 m /day, in addition circulation to the transport of mud, sand, biogenic material, nutrients, and pollutants. -

SEDIMENTARY FRAMEWORK of Lmainland FRINGING REEF DEVELOPMENT, CAPE TRIBULATION AREA

GREAT BARRIER REEF MARINE PARK AUTHORITY TECHNICAL MEMORANDUM GBRMPA-TM-14 SEDIMENTARY FRAMEWORK OF lMAINLAND FRINGING REEF DEVELOPMENT, CAPE TRIBULATION AREA D.P. JOHNSON and RM.CARTER Department of Geology James Cook University of North Queensland Townsville, Q 4811, Australia DATE November, 1987 SUMMARY Mainland fringing reefs with a diverse coral fauna have developed in the Cape Tribulation area primarily upon coastal sedi- ment bodies such as beach shoals and creek mouth bars. Growth on steep rocky headlands is minor. The reefs have exten- sive sandy beaches to landward, and an irregular outer margin. Typically there is a raised platform of dead nef along the outer edge of the reef, and dead coral columns lie buried under the reef flat. Live coral growth is restricted to the outer reef slope. Seaward of the reefs is a narrow wedge of muddy, terrigenous sediment, which thins offshore. Beach, reef and inner shelf sediments all contain 50% terrigenous material, indicating the reefs have always grown under conditions of heavy terrigenous influx. The relatively shallow lower limit of coral growth (ca 6m below ADD) is typical of reef growth in turbid waters, where decreased light levels inhibit coral growth. Radiocarbon dating of material from surveyed sites confirms the age of the fossil coral columns as 33304110 ybp, indicating that they grew during the late postglacial sea-level high (ca 5500-6500 ybp). The former thriving reef-flat was killed by a post-5500 ybp sea-level fall of ca 1 m. Although this study has not assessed the community structure of the fringing reefs, nor whether changes are presently occur- ring, it is clear the corals present today on the fore-reef slope have always lived under heavy terrigenous influence, and that the fossil reef-flat can be explained as due to the mid-Holocene fall in sea-level. -

Background Document for Deep-Sea Sponge Aggregations 2010

Background Document for Deep-sea sponge aggregations Biodiversity Series 2010 OSPAR Convention Convention OSPAR The Convention for the Protection of the La Convention pour la protection du milieu Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic marin de l'Atlantique du Nord-Est, dite (the “OSPAR Convention”) was opened for Convention OSPAR, a été ouverte à la signature at the Ministerial Meeting of the signature à la réunion ministérielle des former Oslo and Paris Commissions in Paris anciennes Commissions d'Oslo et de Paris, on 22 September 1992. The Convention à Paris le 22 septembre 1992. La Convention entered into force on 25 March 1998. It has est entrée en vigueur le 25 mars 1998. been ratified by Belgium, Denmark, Finland, La Convention a été ratifiée par l'Allemagne, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, la Belgique, le Danemark, la Finlande, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, la France, l’Irlande, l’Islande, le Luxembourg, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom la Norvège, les Pays-Bas, le Portugal, and approved by the European Community le Royaume-Uni de Grande Bretagne and Spain. et d’Irlande du Nord, la Suède et la Suisse et approuvée par la Communauté européenne et l’Espagne. Acknowledgement This document has been prepared by Dr Sabine Christiansen for WWF as lead party. Rob van Soest provided contact with the surprisingly large sponge specialist group, of which Joana Xavier (Univ. Amsterdam) has engaged most in commenting on the draft text and providing literature. Rob van Soest, Ole Tendal, Marc Lavaleye, Dörte Janussen, Konstantin Tabachnik, Julian Gutt contributed with comments and updates of their research. -

A Research Overview of the Siltation Loss Controls and Capacity Recovery Processes in China’S Reservoirs

MATEC Web of Conferences 246, 01086 (2018) https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/201824601086 ISWSO 2018 A Research Overview of the Siltation Loss Controls and Capacity Recovery Processes in China’s Reservoirs H H Hu, A J Deng, J G Chen, H L Shi and M Ye China Institute of Water Resources and Hydropower Research, Beijing, China Abstract. There are many reservoirs in China with serious siltation issues which are affecting the function and safety of the reservoirs. Recently, research studies have been carried out regarding siltation loss control and capacity recovery technology due to the decreases in suitable dam sites for establishing reservoirs, and the increasingly serious siltation losses which have been occurring in the present reservoirs. The results of these studies have been of great significance to the partial recoveries of the siltation capacities of reservoirs, improvements in the respective efficiencies of the current reservoirs, and the prolonging of the service life the reservoirs. This study presented a simple review of the previous research findings regarding the current siltation loss situations and controls, as well as the capacity recoveries which have been achieved. Also, this study proposed the urgent need for in-depth examinations to be conducted pertaining to the national investigations of the reservoir siltation status in China, as well as a review of the current mechanisms and control measures for reservoir siltation losses. 1 Introduction At the present time, millions of different dams have been built around the world, which include 50,000 large dams, China has the largest number of reservoirs among all forming a global reservoir capacity of approximately 7 countries of the world. -

Impacts of Sediment Burial on Mangroves

Marine Pollution Bulletin Vol. 37, Nos. 8±12, pp. 420±426, 1998 Ó 1999 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved Printed in Great Britain PII: S0025-326X(98)00122-2 0025-326X/99 $ - see front matter Impacts of Sediment Burial on Mangroves JOANNA C. ELLISON School of Applied Science, University of Tasmania, P.O. Box 1214, Launceston, Tasmania 7250, Australia Aerial roots are a common adaptation of mangrove trees Rates of Mangrove Tidal Swamp Accretion to their saline wetland habitat, allowing root respiration in the anaerobic substrate. While mangroves ¯ourish on First, it is necessary to establish natural rates of sedi- sedimentary shorelines, it is shown here that excess input mentation, for mangroves are known to promote sedi- of sediment to mangroves can cause death of trees owing mentation. Scon (1970) showed that the roots of to root smothering. Descriptions of 26 cases were found in Rhizophora mangle can signi®cantly reduce the velocity the literature or described here, where mangroves have of tidal water, and provide a better sediment binding been adversely aected by sediment burial of roots. The capacity compared with a variety of sea-grasses and impacts ranged from reduced vigour to death, depending algal mats. Furukawa and Wolanski (1996) and Fur- on the amount and type of sedimentation, and the species ukawa et al. (1997) demonstrated that a combination of involved. There are insucient data to establish speci®c vegetational friction on water movement and sediment tolerances. For rehabilitation, where the disturbance was a ¯occulation promotes sedimentation within mangrove past event, the elevation change must be assessed in swamps. -

Life on the Coral Reef

Coral Reef Teacher’s Guide Life on the Coral Reef Life on the Coral Reef THE CORAL REEF ECOSYSTEM The muddy silt drifts out to sea, covering the nearby Coral reefs provide the basis for the most productive coral reefs. Some corals can remove the silt, but many shallow water ecosystem in the world. An ecosystem cannot. If the silt is not washed off within a short pe- is a group of living things, such as coral, algae and riod of time by the current, the polyps suffocate and fishes, along with their non-living environment, such die. Not only the rainforest is destroyed, but also the as rocks, water, and sand. Each influences the other, neighboring coral reef. and both are necessary for the successful maintenance of life. If one is thrown out of balance by either natural Reef Zones or human-made causes, then the survival of the other Coral reefs are not uniform, but are shaped by the is seriously threatened. forces of the sea and the structure of the sea floor into DID YOU KNOW? All of the Earth’s ecosystems are a series of different parts or reef zones. Understand- interrelated, forming a shell of life that covers the ing these zones is useful in understanding the ecol- entire planet – the biosphere. For instance, if too many ogy of coral reefs. Keep in mind that these zones can trees are cut down in the rainforest, soil from the for- blend gradually into one another, and that sometimes est is washed by rain into rivers that run to the ocean. -

Deep-Sea Life Issue 14, January 2020 Cruise News E/V Nautilus Telepresence Exploration of the U.S

Deep-Sea Life Issue 14, January 2020 Welcome to the 14th edition of Deep-Sea Life (a little later than anticipated… such is life). As always there is bound to be something in here for everyone. Illustrated by stunning photography throughout, learn about the deep-water canyons of Lebanon, remote Pacific Island seamounts, deep coral habitats of the Caribbean Sea, Gulf of Mexico, Southeast USA and the North Atlantic (with good, bad and ugly news), first trials of BioCam 3D imaging technology (very clever stuff), new deep pelagic and benthic discoveries from the Bahamas, high-risk explorations under ice in the Arctic (with a spot of astrobiology thrown in), deep-sea fauna sensitivity assessments happening in the UK and a new photo ID guide for mesopelagic fish. Read about new projects to study unexplored areas of the Mid-Atlantic Ridge and Azores Plateau, plans to develop a water-column exploration programme, and assessment of effects of ice shelf collapse on faunal assemblages in the Antarctic. You may also be interested in ongoing projects to address and respond to governance issues and marine conservation. It’s all here folks! There are also reports from past meetings and workshops related to deep seabed mining, deep-water corals, deep-water sharks and rays and information about upcoming events in 2020. Glance over the many interesting new papers for 2019 you may have missed, the scientist profiles, job and publishing opportunities and the wanted section – please help your colleagues if you can. There are brief updates from the Deep- Ocean Stewardship Initiative and for the deep-sea ecologists amongst you, do browse the Deep-Sea Biology Society president’s letter. -

Siltation Mitigation Proposals

Proposed Kaimai Windfarm Roading and Turbine Site Earthworks Siltation Mitigation Proposals Introduction In preparing this report, I have considered and incorporated the following: 1. Memorandum – Kaimai Turbine Dimensions – Rev 4; 21 May 2018: Kaimai Windfarm Ltd 2. Civil Engineering Drawings – Resource Consent Issue; Rev A; Tektus Consultants; June 2018 3. Civil Engineering Peer review; May 2018; Tiaki Consultants Background Information The wind farm proposal involves siting 24 wind turbines as detailed on the topographical plans 200, 200-1 to 200-7 as prepared by Tektus Consultants. A lidar survey has provided ground contours shown at 2.0m intervals. From the above described plans a proposed roading network (comprising of approximately 18.5 km of roading), provides access to and links the proposed wind turbine sites. The proposed roading network naturally utilises existing roads and farm tracks which comprise of approximately 13 km length of road. The remaining 5 - 6 km of new roading traverses grassed steep to rolling farmland along ridges to the proposed wind turbine sites. Each of the turbine sites are essentially cut into the natural ground to ensure the structures are founded appropriately. Each of the sites has an area of flat ground adjoining the actual turbine foundation that will serve as an assembly/construction platform. A geotechnical report prepared by KGA Geotechnical provides some recommendations regarding road and turbine foundation construction and is consistent with accepted practice. Site Preparation for Earthworks The purpose of this report is to outline the design concepts for Siltation Mitigation methods to be carried out within the property(s) concerned and ensure the earthworks construction phase of the proposed Kaimai Windfarm can proceed in a sensible and practical way while addressing the necessary environmental and regulatory requirements. -

Impacts to Marine Fisheries Habitat from Nonfishing Activities in the Northeastern United States

NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS-NE-209 Impacts to Marine Fisheries Habitat from Nonfishing Activities in the Northeastern United States US DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Northeast Regional Office Gloucester, Massachusetts February 2008 Recent Issues in This Series: 191. Essential Fish Habitat Source Document: Northern Shortfin Squid, Illex illecebrosus, Life History and Habitat Characteristics. 2nd ed. By Lisa C. Hendrickson and Elizabeth M. Holmes. November 2004. v + 36 p., 13 figs., 1 table. NTIS Access. No. PB2005- 101437. [Online publication only.] 192. Essential Fish Habitat Source Document: Atlantic Herring, Clupea harengus, Life History and Habitat Characteristics. 2nd ed. By David K. Stevenson and Marcy L. Scott. July 2005. vi + 84 p., 40 figs., 7 tables. NTIS Access. No. PB2005-107567. [Online publication only.] 193. Essential Fish Habitat Source Document: Longfin Inshore Squid, Loligo pealeii, Life History and Habitat Characteristics. 2nd ed. By Larry D. Jacobson. August 2005. v + 42 p., 20 figs., 1 table. NTIS Access. No. PB2005-110684. [Online publication only.] 194. U.S. Atlantic and Gulf of Mexico Marine Mammal Stock Assessments -- 2005. By Gordon T. Waring, Elizabeth Josephson, Carol P. Fairfield, and Katherine Maze-Foley, eds. Dana Belden, Timothy V.N. Cole, Lance P. Garrison, Keith D. Mullin, Christopher Orphanides, Richard M. Pace III, Debra L. Palka, Marjorie C. Rossman, and Fredrick W. Wenzel, contribs. March 2006. v + 392 p., 45 figs, 79 tables, 5 app., index. NTIS Access No. PB 2007-104395. 195. A Large Marine Ecosystem Voluntary Environmental Management System Approach to Fisheries Practices. By Frank J. Gable. December 2005. -

Mechanism of Back Siltation in Navigation Channel in Dinh an Estuary, Vietnam

Water Science and Engineering, 2013, 6(2): 178-188 doi:10.3882/j.issn.1674-2370.2013.02.006 http://www.waterjournal.cn e-mail: [email protected] Mechanism of back siltation in navigation channel in Dinh An Estuary, Vietnam Viet-Thanh NGUYEN1, 2, 3, Jin-hai ZHENG*1, 2, Ji-sheng ZHANG1, 2 1. State Key Laboratory of Hydrology-Water Resources and Hydraulic Engineering, Hohai University, Nanjing 210098, P. R. China 2. College of Harbor, Coastal and Offshore Engineering, Hohai University, Nanjing 210098, P. R. China 3. Faculty of Civil Engineering, University of Transport and Communications, Hanoi, Vietnam Abstract: The Dinh An Estuary is one of the Nine Dragon estuaries of the Mekong River. An international navigation channel was built in the estuary for vessels traveling from the South China Sea to the southwestern area of Vietnam and then to Phnom Penh, Cambodia. The morphological evolution of the navigation channel is complicated and unstable. The back siltation intensity in the navigation channel has largely increased and been concentrated in the curvature segments of the channel since 1980. In this study, based on simulation results and measured data, five key factors that influence the back siltation in the navigation channel were systematically analyzed. These factors included the increasing elevation gap between the channel and the nearby seabed, the disadvantageous hydrodynamic conditions, sediment transport, mixing of saltwater and freshwater, and wave effects in the navigation channel. It is shown that the back siltation to a large extent results from the low current velocity of the secondary ocean circulation, which often occurs in the curvature segments of the channel. -

2005 Artificial Reef Management Plan

ARTIFICIAL REEF MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR NEW JERSEY December, 2005 Richard J. Codey, Acting Governor State of New Jersey Bradley M. Campbell, Commissioner Department of Environmental Protection John S. Watson Jr., Assistant Commissioner Natural and Historic Resources Martin J. McHugh, Director Division of Fish and Wildlife Marine Fisheries Council: Gilbert Ewing Jr., Chairman Dr. Robert B. Abel Richard Herb Erling Berg Nancy Sittineri Joseph Rizzo Dr. Patrick Donnelly Edward Goldman John Maxwell Francis Puskas Prepared By: Bill Figley Principal Fisheries Biologist New Jersey’s Reef Program is partially funded by the Federal Sport Fish Restoration Program. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS………………………………….…………………i LIST OF FIGURES…………………………………………………………vi LIST OF TABLES…….………………………………………………...…vii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS….………..……………………………………viii A MESSAGE FROM THE COMMISSIONER……………………………ix EXECUTIVE SUMMARY……….………………………………....….…..xi ARTIFICIAL REEF MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR NEW JERSEY...…..xiii 1.0 OBJECTIVES OF NEW JERSEY’S ARTIFICIAL REEF PROGRAM …………………………………………………………..1 1.1 Definitions of Natural and Artificial Reefs……………………2 1.2 Department Policy……………………………………………..2 1.3 Reef Plan Authority……………………………………………8 1.4 Reef Program Goal…………………………………………….8 2.0 FACTORS PROMPTING THE NEW JERSEY ARTIFICIAL REEF PROGRAM…………………………………………………....9 2.1 Loss or Lack of Hard-Substrate Fish Habitat……...…...…..….9 2.2 Recreational Fishing Effort…………...………....…………....10 2.3 Commercial Fishing Effort………………………...……..…..11 3.0 EFFECTS OF ARTIFICIAL REEFS………………………………..12 3.1 Attributes