Estimating the Potential Risks of Sea Level Rise for Public and Private Property Ownership, Occupation and Management

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

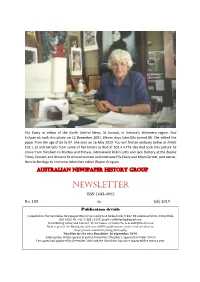

Ella Ebery as editor of the North Central News, St Arnaud, in Victoria’s Wimmera region. Rod Kirkpatrick took this photo on 12 December 2001. Eleven days later Ella turned 86. She edited the paper from the age of 63 to 97. She died on 16 May 2019. You will find an obituary below at ANHG 103.1.13 and extracts from some of her letters to Rod at 103.4.4.The day Rod took this picture he drove from Horsham to Murtoa and Minyip, interviewed Robin Letts and Jack Slattery at the Buloke Times, Donald, and drove to St Arnaud to meet and interview Ella Ebery and Brian Garrett, part owner, then to Bendigo to interview Advertiser editor Wayne Gregson. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 103 m July 2019 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, U 337, 55 Linkwood Drive, Ferny Hills, Qld, 4055. Ph. +61-7-3351 6175. Email: [email protected] Contributing editor and founder: Victor Isaacs, of Canberra, is at [email protected] Back copies of the Newsletter and some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 30 September 2019. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000 and the Newsletter has since appeared five times a year. 1—Current Developments: National & Metropolitan Index to issues 1-100: thanks Thank you to the subscribers who contributed to the appeal for $650 to help fund the index to issues 76 to 100 of the ANHG Newsletter, with the index to be incorporated in a master index covering Nos. -

Amelia Coleman Thesis

Different, threatening and problematic: Representations of non- mainstream religious schools (Chang, 2016) Amelia Coleman N8306869 Bachelor of Media and Communications (Public Relations) Queensland University of Technology Supervised by Dr Shaun Nykvist (Principal) Dr Rebecca English (Associate) Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education (Research) Office of Education Research (OER) Faculty of Education Queensland University of Technology 2017 Keywords School choice Media representation Religious schools Multicultural education Marketisation Discourse Identity Pluralism ii Abstract Over recent years we have seen a dramatic increase in representation of Muslim schools within the Australian media. This thesis presents the findings of a study comparing media representations of Muslim schools and “fundamentalist” Christian schools in Australia during a 12-month period in which Muslim schools were receiving significant media attention due to financial mismanagement issues occurring within these schools. During this time period an allegation was made that thousands of dollars of taxpayer funding was being sent to Muslim school’s parent organisation, AFIC, rather than being spent on the education of students (Taylor, 2016). The study focused on comparing how Muslim schools and “fundamentalist” Christian schools were constructed by the media during the timeframe in which Muslim schools were under investigation, and how their media representation may become a proxy for understanding how the Australian public are invited to feel about different types of religious schools. The study draws together Fairclough’s framework for Critical Discourse Analysis with Hall’s work on identity and cultural difference in order to explore inequalities that exist within representations of different varieties of non-mainstream religious schools in Australia. -

Villages Daily Sun Inks Press, Postpress Deals for New Production

www.newsandtech.com www.newsandtech.com September/October 2019 The premier resource for insight, analysis and technology integration in newspaper and hybrid operations and production. Villages Daily Sun inks press, postpress deals for new production facility u BY TARA MCMEEKIN CONTRIBUTING WRITER The Villages (Florida) Daily Sun is on the list of publishers which is nearer to Orlando. But with development trending as winning the good fight when it comes to community news- it is, Sprung said The Daily Sun will soon be at the center of the papering. The paper’s circulation is just over 60,000, and KBA Photo: expanded community. — thanks to rapid growth in the community — that number is steadily climbing. Some 120,000 people already call The Partnerships key Villages home, and approximately 300 new houses are being Choosing vendors to supply various parts of the workflow at built there every month. the new facility has been about forming partnerships, accord- To keep pace with the growth, The Daily Sun purchased a Pictured following the contract ing to Sprung. Cost is obviously a consideration, but success brand-new 100,000-square-foot production facility and new signing for a new KBA press in ultimately depends on relationships, he said — both with the Florida: Jim Sprung, associate printing equipment. The publisher is confident the investment publisher for The Villages Media community The Daily Sun serves and the technology providers will help further entrench The Daily Sun as the definitive news- Group; Winfried Schenker, senior who help to produce the printed product. paper publisher and printer in the region. -

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

Some front pages from Melbourne’s Herald Sun (Australia’s biggest selling daily) during 2016. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 91 February 2017 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, U 337, 55 Linkwood Drive, Ferny Hills, Qld, 4055. Ph. +61-7-3351 6175. Email: [email protected] Contributing editor and founder: Victor Isaacs, of Canberra, is at [email protected] Back copies of the Newsletter and some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 30 April 2017. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000 and the Newsletter has since appeared five times a year. 1—Current Developments: National & Metropolitan 91.1.1 Fairfax sticks to print but not to editors-in-chief Fairfax Media chief executive Greg Hywood has said the company will “continue to print our publications daily for some years yet”. Hywood said this in mid-February in an internal message to staff after appointing a digital expert, Chris Janz, to run its flagship titles, the Sydney Morning Herald, Melbourne’s Age and the Australian Financial Review. Janz, formerly the director of publishing innovation, is now the managing director of Fairfax’s metro publishing unit. Hywood said, “Chris has been overseeing the impressive product and technology development work that will be the centrepiece of Metro’s next-generation publishing model.” Janz had run Fairfax’s joint venture with the Huffington Post and before that founded Allure Media, which runs the local websites of Business Insider, PopSugar and other titles under licence (Australian, 15 February 2017). -

Evidence Based Policy Research Project 20 Case Studies

October 2018 EVIDENCE BASED POLICY RESEARCH PROJECT 20 CASE STUDIES A report commissioned by the Evidence Based Policy Research Project facilitated by the newDemocracy Foundation. Matthew Lesh, Research Fellow This page intentionally left blank EVIDENCE BASED POLICY RESEARCH PROJECT 20 CASE STUDIES Matthew Lesh, Research Fellow About the author Matthew Lesh is a Research Fellow at the Institute of Public Affairs Matthew’s research interests include the power of economic and social freedom, the foundations of western civilisation, university intellectual freedom, and the dignity of work. Matthew has been published on a variety of topics across a range of media outlets, and provided extensive commentary on radio and television. He is also the author of Democracy in a Divided Australia (2018). Matthew holds a Bachelor of Arts (Degree with Honours), from the University of Melbourne, and an MSc in Public Policy and Administration from the London School of Economics. Before joining the IPA, he worked for state and federal parliamentarians and in digital communications, and founded a mobile application Evidence Based Policy Research Project This page intentionally left blank Contents Introduction 3 The challenge of limited knowledge 3 A failure of process 4 Analysis 5 Limitations 7 Findings 8 Federal 9 Abolition and replacement of the 457 Visa 9 Australian Marriage Law Postal Survey 13 Creation of ‘Home Affairs’ department 16 Electoral reform bill 19 Enterprise Tax Plan (Corporate tax cuts) 21 Future Submarine Program 24 Media reform bill 26 -

Media Release

Media Release 24 April, 2014 The Daily Telegraph and NewsLocal launch phase two of their ‘Fair Go for the West’ campaign: ‘Champions of the West’ grants program The Daily Telegraph and NewsLocal have launched ‘Champions of the West’, a grants program that will support local community initiatives in Australia’s third largest economic region, Western Sydney. ‘Champions of the West’ will award twelve $10,000 grants to individuals, groups and businesses that require funding to launch projects that will make a difference in their community. It will then recognise and celebrate the individuals behind the initiatives. A panel of judges, including Brett Clegg, State Director, News NSW; Katie Page, CEO, Harvey Norman; and Professor Barney Glover, Vice-Chancellor, University of Western Sydney, will choose the winners, who will be announced at an event on Tuesday 3 June 2014. ‘Champions of the West’ is a key part of The Daily Telegraph and NewsLocal’s ‘Fair Go for the West’ campaign that aims to improve infrastructure and increase focus on Western Sydney. The Daily Telegraph deputy editor Ben English said: “The Champions of the West program was established to celebrate and reward innovation in this exciting and vibrant section of Sydney. And with the support of our corporate partners, and also CH7 News and Nova 96.9, we are sure to uncover some exciting new projects that will benefit the community for years to come. “We are already overwhelmed by the quality and breadth of Champions that have been nominated for the $10,000 grants. Deciding who gets -

2018 TERMS and CONDITIONS 1. Information on How

2018 TERMS AND CONDITIONS 1. Information on how to participate forms part of the terms and conditions. Your participation as described below is deemed acceptance of these terms and conditions. 2. The Promoter is Nationwide News Pty Ltd (ABN 98 008 438 828) of 2 Holt Street Surry Hills NSW 2010. 3. Participation is open to all Australian residents aged 13 years and over. Participants under the age of 18 must obtain prior permission of their legal parent or guardian over the age of 18 to enter. 4. How to participate in Snap Australia: a. Photos must be taken in Australia between 8 May, 2018 to 30 December, 2018 and be originals. b. Participate through any of the following social media platforms: (i) Twitter: Tweet your photo with #Snap[REGION] publication as per the publication/hashtag list below. It is optional to tag or @mention your News Corp Australia publication. (ii) Instagram: Post your photo with #Snap[REGION] as per the publication/hashtag list below. Ensure your profile is public to ensure visibility. It is optional to tag or @mention your News Corp Australia publication. (iii) Facebook: Post your photo with #Snap[REGION] as per the publication/hashtag list below. Ensure your post is public to ensure visibility. It is optional to tag or @mention your News Corp Australia publication. c. The following News Corp Australia publications are participating using the following hashtags and tags on Instagram (and these need to be referenced as per the below instructions for the different platforms): @thecairnspost Cairns Post #SnapCairns -

ANNUAL REPORT 2015-2016 No

ANNUAL REPORT 2015-2016 No. 40 The Australian Press Council Address: Level 6, 309 Kent Street Sydney 2000 Phone: (02) 9261 1930 or 1800 025 712 Fax: (02) 9267 6826 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.presscouncil.org.au ANNUAL REPORT 2015-2016 Annual Report No. 40 Year ending 30 June 2016 Level 6, 309 Kent Street SYDNEY NSW 2000 Australia Telephone: (02) 9261 1930 1 800 025 712 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.presscouncil.org.au ISSN 0156-1308 Chair’s Foreword This Annual Report covers the financial year 2015-2016, a period characterised both by consolidation and remarkable change. First and foremost, the Australian Press Council celebrated its 40th anniversary with a major international conference on press freedom in Sydney in May 2016. The conference was a huge success, bringing together all parts of the news media in Australia to discuss the critical issues facing us. The Conference was very well-supported by Council members and other sponsors, enabling us to fly in a number of international journalism stars to add a richness and gravitas to the occasion. (See Chapter 5 and Appendix 6.) When the Council was first established in 1976, it was a fragile body. Few paediatricians would have given it 40 years or more to live. There have certainly been ups and down over the decades, but the Council is now firmly fixed in the media landscape and playing a very active and positive role in the interests of both publishers and the general community. The Press Council’s first Strategic Plan All Press Council members and Secretariat staff engaged in a highly collegial process to develop, workshop and finally approve the organisation’s first ever Strategic Plan, covering 2016-2020. -

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

Few country newspapers have equalled the Border Watch, Mount Gambier, South Australia, for the excellence of its newspapers file room. When your editor visited, on 3 February 2003, the file room was not only spotless but well organised and comprehensive. Alan Hill, general manager at the time, is in the picture. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 87 May 2016 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, PO Box 8294 Mount Pleasant Qld 4740. Ph. +61-7-400 031 614. Email: [email protected]/ Contributing editor and founder: Victor Isaacs, of Canberra, is at [email protected]/ Back copies of the Newsletter and some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 15 July 2016. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000 and the Newsletter has since appeared five times a year. 1—Current Developments: National & Metropolitan Housekeeping: ANHG editor Rod Kirkpatrick is moving from Mackay to Brisbane on 23 April. Initially he will not have a fixed residential address. Mail will be forwarded from his Mount Pleasant (Mackay) PO Box to the appropriate postal address. His email address and Mobile phone number (see Page 1) will remain unchanged. 87.1.1 Fairfax Media slashes 120 editorial jobs in Sydney, Melbourne Fairfax Media journalists voted on 17 March to strike until 21 March, after the company told staff it was planning to slash 120 editorial jobs—about one-fifth of the 700 to 750 staff—across its Sydney and Melbourne newsrooms. -

Al-Furat [email protected] An-Nahar [email protected]

Al-Furat [email protected] An-Nahar [email protected] Area News, The [email protected] Armidale Express Extra, The [email protected] Armidale Express, The [email protected] Armidale Independent, The [email protected] Auburn Review [email protected] Australian Chinese Daily [email protected] Australian Chinese News, The [email protected] Australian News Express Daily [email protected] Ballina Shire Advocate [email protected] Bankstown-Canterbury Torch [email protected] Barraba Gazette [email protected] Barrier Daily Truth [email protected] Batemans Bay Post [email protected] Bega District News [email protected] Bellingen Shire Courier-Sun, The [email protected] Bingara Advocate, The [email protected] Blacktown Advocate [email protected] Blacktown Sun [email protected] Blayney Chronicle [email protected] Blue Mountains Gazette [email protected] Bombala Times, The [email protected] Bondi View, The [email protected] Boorowa News, The [email protected] Braidwood Times, The [email protected] Bush Telegraph Weekly, The [email protected] Byron Shire Echo, The [email protected] Byron Shire News [email protected] Camden-Narellan Advertiser [email protected] Campbelltown Macarthur Advertiser [email protected] Canowindra News [email protected] -

Australian Newspaper History Indexed

Australian Newspaper History Indexed An Index to the Australian Newspaper History Group Newsletter Numbers 1 to 75 (1999-2013) Compiled by Karen Gillen Edited by Rod Kirkpatrick First published in 2014 by Australian Newspaper History Group 41 Monterrico Circuit Beaconsfield (Mackay) Queensland 4740 © Australian Newspaper History Group This publication is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be addressed to the publisher. The Australian Newspaper History Group. Indexer: Gillen, Karen. Editor: Kirkpatrick, Rod. Australian Newspaper History Indexed: An Index to the Australian Newspaper History Group Newsletter, issues 1 to 75 (1999-2014) ISBN 978 0 9751552 5 7 Australian Newspaper History Indexed Page 2 Foreword By Rod Kirkpatrick, editor, Australian Newspaper History Group Newsletter This is the third index to the Australian Newspaper History Group Newsletter, which began publication in October 1999. Karen Gillen, of Melbourne, has compiled the three indexes. The first, appearing in 2004 and covering issues 1 to 25, was published only as a printed version. The second, a composite index covering issues 1 to 50 (October 1999 to December 2008) was published in 2009 in both printed and digital form. This third index, published in January 2014, covers issues 1 to 75 (October 1999 to December 2013) and is in digital form only. The Australian Newspaper History Group (ANHG) grew out of a three-day conference on local newspapers at an historic newspaper site – Chiltern, Victoria, home of the Federal Standard, published from 1859 until 1970. -

Indigenous Invisibility in the City

Indigenous Invisibility in the City Indigenous Invisibility in the City contextualises the significant social change in Indigenous life circumstances and resurgence that came out of social movements in cities. It is about Indigenous resurgence and community development by First Nations people for First Nations people in cities. Seventy-five years ago, First Nations peoples began a significant post-war period of relocation to cities in the United States, Canada, Australia, and Aotearoa New Zealand. First Nations peoples engaged in projects of resurgence and community development in the cities of the four settler states. First Nations peoples, who were motivated by aspirations for autonomy and empowerment, went on to create the foundations of Indigenous social infrastructure. This book explains the ways First Nations people in cities created and took control of their own futures. A fact largely wilfully ignored in policy contexts. Today, differences exist over the way governments and First Nations peoples see the role and responsibilities of Indigenous institutions in cities. What remains hidden in plain sight is their societal function as a social and political apparatus through which much of the social processes of Indigenous resurgence and community development in cities occurred. The struggle for self-determination in settler cities plays out through First Nations people’s efforts to sustain their own institutions and resurgence, but also rights and recognition in cities. This book will be of interest to Indigenous studies scholars, urban sociologists, urban political scientists, urban studies scholars, and development studies scholars interested in urban issues and community building and development. Deirdre Howard-Wagner is a sociologist and associate professor with the Australian National University.