Evidence Based Policy Research Project 20 Case Studies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No

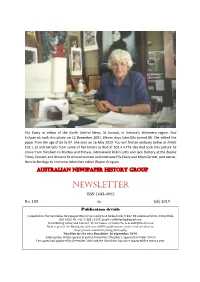

Ella Ebery as editor of the North Central News, St Arnaud, in Victoria’s Wimmera region. Rod Kirkpatrick took this photo on 12 December 2001. Eleven days later Ella turned 86. She edited the paper from the age of 63 to 97. She died on 16 May 2019. You will find an obituary below at ANHG 103.1.13 and extracts from some of her letters to Rod at 103.4.4.The day Rod took this picture he drove from Horsham to Murtoa and Minyip, interviewed Robin Letts and Jack Slattery at the Buloke Times, Donald, and drove to St Arnaud to meet and interview Ella Ebery and Brian Garrett, part owner, then to Bendigo to interview Advertiser editor Wayne Gregson. AUSTRALIAN NEWSPAPER HISTORY GROUP NEWSLETTER ISSN 1443-4962 No. 103 m July 2019 Publication details Compiled for the Australian Newspaper History Group by Rod Kirkpatrick, U 337, 55 Linkwood Drive, Ferny Hills, Qld, 4055. Ph. +61-7-3351 6175. Email: [email protected] Contributing editor and founder: Victor Isaacs, of Canberra, is at [email protected] Back copies of the Newsletter and some ANHG publications can be viewed online at: http://www.amhd.info/anhg/index.php Deadline for the next Newsletter: 30 September 2019. Subscription details appear at end of Newsletter. [Number 1 appeared October 1999.] Ten issues had appeared by December 2000 and the Newsletter has since appeared five times a year. 1—Current Developments: National & Metropolitan Index to issues 1-100: thanks Thank you to the subscribers who contributed to the appeal for $650 to help fund the index to issues 76 to 100 of the ANHG Newsletter, with the index to be incorporated in a master index covering Nos. -

DSD Annual Report 2016-17

Preparations in Townsville ahead of Tropical Cyclone Debbie. Delivering for the community that will contribute towards implementing Queensland Queensland’s vision. Government’s More information on how our policies, programs and services contribute to the objectives for the government’s objectives for the community can be found in the ‘Our performance’ community sections of this annual report. Our department is focused on delivering the following Queensland Government objectives Whole-of-government plans for the community: and initiatives • creating jobs and a diverse economy • building safe, caring and connected National Partnership Agreements communities and Project Agreements • protecting the environment. The department has the lead responsibility for We collaborate with local, state and federal delivering on two National Partnership government agencies, industry and private Agreements (NPAs) with the Australian sector stakeholders to deliver quality frontline Government. services, and to: The aim of the NPAs is to improve the capacity, resilience and infrastructure in • support and increase job opportunities through major project communities, and to implement financial development and the growth of new management frameworks that build the and existing industry sectors capacity and resilience of local governments. • encourage partnerships with regional Regional Infrastructure Fund stakeholders and grow regional Stream 2—Economic Infrastructure economies through investment, exports and job creation North Queensland Resources Supply Chain -

Submission of Abc Alumni Limited to Senate Standing Committee on Environment and Communications

1 SUBMISSION OF ABC ALUMNI LIMITED TO SENATE STANDING COMMITTEE ON ENVIRONMENT AND COMMUNICATIONS 13 November 2018 _______________________________________________ INTRODUCTORY STATEMENT ABC Alumni Limited represents a community of former staff and supporters of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. We campaign for properly funded, high quality, independent, ethical, and free public media in Australia. We promote excellence across all platforms through education, mentoring, public forums and scholarships. The selection of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation’s Board and Managing Director must be free of political favouritism. Funding for the ABC must be guaranteed. We welcome this inquiry into ‘allegations of political interference in the Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC)’. It is vitally important that the Senate committee establishes the detail; the who, what, where and, most importantly, why of Managing Director Michelle Guthrie’s dismissal and Board Chair Justin Milne’s subsequent resignation. We are alarmed by the widely publicised allegations made by Ms Guthrie about the conduct of Mr Milne (and any possible complicity by Board directors; for example, was there a failure to act on the allegations when presented with them?). Ms Guthrie’s allegations if true, in whole or in part, clearly indicate that the current legislation and Chair/Board appointment processes fail to protect the ABC from overt and covert political interference. This makes the corporation vulnerable to punitive funding cuts that affect its ability to continue to provide the range and quality of fearless, independent broadcasting and online publishing for which it is known. These issues are fundamental to the important contribution the ABC makes to Australian society. In our view there is a need for amendments to the ABC Act and for changes to existing processes for the appointment of the Chair and Board directors. -

Hon. Cameron Dick

Speech by Hon. Cameron Dick MEMBER FOR GREENSLOPES Hansard Wednesday, 22 April 2009 MAIDEN SPEECH Hon. CR DICK (Greenslopes—ALP) (Attorney-General and Minister for Industrial Relations) (7.30 pm): I start tonight by acknowledging the traditional owners of the land where this parliament stands who have served and nurtured this land for centuries. I pay tribute to them and their great role in our history. It is in this reflection of history that I begin tonight. In December 1862, three short years after the birth of our great state, whose 150th anniversary we celebrate this year, the sailing ship Conway arrived in the small Queensland settlement then known as Moreton Bay. History little records the fate of the Conway, its passengers and its crew, but one thing is known about that day in December 1862: that is the day my family arrived in Queensland and began its Queensland journey. Almost 150 years later, that journey has taken me to this place, the Queensland parliament. I stand tonight as a representative of the people in our state’s legislature, not only as a fifth-generation Queenslander but also with great humility and honour as a son of the state seat of Greenslopes, the electorate I now serve as a member of parliament. My first thanks this evening go to those people who make up the community of Greenslopes. It is a wonderful and diverse community and I look forward to serving them to the best of my ability. This electorate is very dear to my heart. It was at Holland Park, in the Greenslopes electorate, that I was raised as a boy. -

Amelia Coleman Thesis

Different, threatening and problematic: Representations of non- mainstream religious schools (Chang, 2016) Amelia Coleman N8306869 Bachelor of Media and Communications (Public Relations) Queensland University of Technology Supervised by Dr Shaun Nykvist (Principal) Dr Rebecca English (Associate) Submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Education (Research) Office of Education Research (OER) Faculty of Education Queensland University of Technology 2017 Keywords School choice Media representation Religious schools Multicultural education Marketisation Discourse Identity Pluralism ii Abstract Over recent years we have seen a dramatic increase in representation of Muslim schools within the Australian media. This thesis presents the findings of a study comparing media representations of Muslim schools and “fundamentalist” Christian schools in Australia during a 12-month period in which Muslim schools were receiving significant media attention due to financial mismanagement issues occurring within these schools. During this time period an allegation was made that thousands of dollars of taxpayer funding was being sent to Muslim school’s parent organisation, AFIC, rather than being spent on the education of students (Taylor, 2016). The study focused on comparing how Muslim schools and “fundamentalist” Christian schools were constructed by the media during the timeframe in which Muslim schools were under investigation, and how their media representation may become a proxy for understanding how the Australian public are invited to feel about different types of religious schools. The study draws together Fairclough’s framework for Critical Discourse Analysis with Hall’s work on identity and cultural difference in order to explore inequalities that exist within representations of different varieties of non-mainstream religious schools in Australia. -

Stadiums Taskforce Report

4.0 Stadiums Queensland Business Model >> Stadium Taskforce - Final Report 61 4.0 Stadiums Queensland Business Model The SQ business model is the way SQ coordinates and strategically manages its asset portfolio responsibilities. The SQ business model takes into consideration items such as SQ’s approach to market testing and outsourcing of services, as well as to the shared support services for the organisation and portfolio and to SQ’s role in stadium planning. At a venue level, the SQ business model incorporates SQ’s consideration and determination of the preferred management approach for each of its venues, taking into account specifics of the asset, the use of the venue and historic operations. SQ’s intent of applying its business model is to implement management arrangements that maximise the likelihood of individual venues and the portfolio as a whole, operating as efficiently as possible. SQ achieves this by employing a variety of venue management, venue operations and venue hiring models, in addition to portfolio-wide arrangements. Market Testing and Outsourcing As a matter of business policy, SQ consistently tests the market to establish whether services are more cost effective if delivered on an outsourced basis. SQ is incentivised to do so because of customer requirements (hirers and patrons) to contain costs so that attending venues for patrons remains affordable. The Taskforce understands that a majority of SQ business is historically outsourced, including stadium services such as ticketing, catering, security, cleaning and waste management and corporate business functions such as audit, incident management, insurance and risk management. The final small percentage of services are directly delivered by SQ if it is more cost effective to do so, or if the risk to the Queensland Government is more effectively managed. -

Work of Committees

WORK OF COMMITTEES Financial Year Statistics: 1 July 2010–30 June 2011 Half-Year Statistics: 1 January 2011–30 June 2011 © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 ISBN 978-1-74229-503-9 This document was printed by the Senate Printing Unit, Parliament House, Canberra CONTENTS Index ..................................................................................................................................... iii Format of this report .............................................................................................................. v Abbreviations ........................................................................................................................ vi General Information ............................................................................................................. vii Directory of Committees....................................................................................................... ix Committees administered by the Senate Committee Office .................................................. x PART ONE: Legislation and References Committees at a glance 1 July 2010–30 June 2011 ...................................................................... 13 PART TWO: Consolidated Statistical Overview (Financial Year) 1 July 2010–30 June 2011 ...................................................................... 17 PART THREE: Matters Referred and Reports Tabled (By Committee) 2001–2011 ............................................................................................... 21 PART FOUR: Consolidated -

Villages Daily Sun Inks Press, Postpress Deals for New Production

www.newsandtech.com www.newsandtech.com September/October 2019 The premier resource for insight, analysis and technology integration in newspaper and hybrid operations and production. Villages Daily Sun inks press, postpress deals for new production facility u BY TARA MCMEEKIN CONTRIBUTING WRITER The Villages (Florida) Daily Sun is on the list of publishers which is nearer to Orlando. But with development trending as winning the good fight when it comes to community news- it is, Sprung said The Daily Sun will soon be at the center of the papering. The paper’s circulation is just over 60,000, and KBA Photo: expanded community. — thanks to rapid growth in the community — that number is steadily climbing. Some 120,000 people already call The Partnerships key Villages home, and approximately 300 new houses are being Choosing vendors to supply various parts of the workflow at built there every month. the new facility has been about forming partnerships, accord- To keep pace with the growth, The Daily Sun purchased a Pictured following the contract ing to Sprung. Cost is obviously a consideration, but success brand-new 100,000-square-foot production facility and new signing for a new KBA press in ultimately depends on relationships, he said — both with the Florida: Jim Sprung, associate printing equipment. The publisher is confident the investment publisher for The Villages Media community The Daily Sun serves and the technology providers will help further entrench The Daily Sun as the definitive news- Group; Winfried Schenker, senior who help to produce the printed product. paper publisher and printer in the region. -

North Queensland Stadium Is a New Venue Built in the City of Highlights Townsville, Seats 25,000 and Will Be the New Home of the NRL’S North Queensland Cowboys

North Townsville, Australia Queensland Stadium SKIDATA INSTALLATIONS North Queensland Stadium is a new venue built in the city of Highlights Townsville, seats 25,000 and will be the new home of the NRL’s North Queensland Cowboys. • 36 Flex.Gate Userboxes and Operator Lights SKIDATA worked with Ticketmaster and Gunnebo for the access solution • SKIDATA's Handshake provided to the new North Queensland Stadium (aka Queensland Country platform communicates Bank Stadium) in Townsville. SKIDATA readers were considered as the with Ticketmaster for ticket most efficient and future-proof solution in the market. information. • The opening night with Elton John attended by over 20 000 people. Project description The new venue was looking for the latest access systems to be aligned with the technology in use by Ticketmaster, partner and ticket provider of the venue. For the first time in Australia, SKIDATA has installed Flex.Gate User Boxes on Gunnebo turnstiles, as requested by the customer. The connection to the ticketing system from Ticketmaster was a standard process via the existing interfaces. The three teams worked together with design, installation and commissioning of the system with very successful results. SKIDATA’s Handshake platform communicates with Ticketmaster for ticket information and reporting. The opening night with Elton John was a great success and the audience of 20 000 people entered the venue smoothly and with no issues thanks to the reliable and fast Handshake.Logic software. The stadium is the new venue of sporting and entertaining events in North Queensland and is also home to the famous North Queensland Cowboys NRL Team. -

Commonwealth of Australia

Commonwealth of Australia Author Wanna, John Published 2019 Journal Title Australian Journal of Politics and History Version Accepted Manuscript (AM) DOI https://doi.org/10.1111/ajph.12576 Copyright Statement © 2019 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics, School of Political Science and International Studies, University of Queensland and Wiley Publishing Asia Pty Ltd. This is the peer reviewed version of the following article: Commonwealth of Australia, Australian Journal of Politics and History, Volume 65, Issue 2, Pages 295-300, which has been published in final form at 10.1111/ajph.12576. This article may be used for non-commercial purposes in accordance with Wiley Terms and Conditions for Self-Archiving Downloaded from http://hdl.handle.net/10072/388250 Griffith Research Online https://research-repository.griffith.edu.au Commonwealth of Australia John Wanna Turnbull’s Bizarre Departure, and a Return to Minority Government for the Morrison-led Coalition Just when political pundits thought federal parliament could not become even wackier than it had been in recent times, the inhabitants of Capital Hill continued to prove everyone wrong. Even serious journalists began referring to the national legislature metaphorically as the “monkey house” to encapsulate the farcical behaviour they were obliged to report. With Tony Abbott being pre-emptively ousted from the prime ministership by Malcolm Turnbull in 2015, Turnbull himself was, in turn, unceremoniously usurped in bizarre circumstances in August 2018, handing over the leadership to his slightly bemused Treasurer Scott Morrison. Suddenly, Australia was being branded as the notorious “coup capital of the Western democracies”, with five prime ministers in five years and only one losing the high office at a general election. -

Lord Mayoral Minute Page 1

THE CITY OF NEWCASTLE Lord Mayoral Minute Page 1 SUBJECT: LMM 28/05/19 - FEDERAL ELECTION RESULTS MOTION That City of Newcastle: 1 Acknowledges the re-election of the Prime Minister, the Hon. Scott Morrsion MP, and the Federal Liberal National Government, following the 18 May 2019 poll; 2 Notes new and returning Ministerial portfolio responsibilities for a number of Minister’s with responsibility for policy regarding local government, including new Minister for Regional Services, Decentralisation and Local Government, the Hon. Mark Coulton MP, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister for Infrastructure, Transport and Regional Development, the Hon. Michael McCormack MP and Minister for Population, Cities and Urban Infrastructure, the Hon. Alan Tudge MP; 3 Congratulates the following local Hunter Members of Parliament on their re-election: • Sharon Claydon MP, Federal Member for Newcastle • Pat Conroy MP, Federal Member for Shortland • Joel Fitzgibbon MP, Federal Member for Hunter • Meryl Swanson MP, Federal Member for Paterson 4 Commits to continuing our collaborative working relationship with the Federal Government and the Federal Labor Opposition for the benefit of the people of the City of Newcastle. BACKGROUND: Following the 2019 Federal election, the Morrison Liberal National Government has formed a majority government. Across Newcastle and the Hunter, all sitting Members of Parliament were returned to represent their communities in the nation’s Parliament. Australians have re-elected our Government to get back to work and get on with the job of delivering for all Australians as they go about their own lives, pursuing their goals and aspirations for themselves, their families and their communities. -

Annual Deregulation Report 2014 Department of Social Services

Annual Deregulation Report 2014 Department of Social Services DSS 1546.03.18 Copyright notice This document Department of Social Services 2014 Annual Deregulation Report is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International Licence Licence URL: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/legalcode Please attribute: © Commonwealth of Australia (Department of Social Services) 2015 Notice: 1. If you create a derivative of this document, the Department of Social Services requests the following notice be placed on your derivative: Based on Commonwealth of Australia (Department of Social Services) data. 2. Inquiries regarding this licence or any other use of this document are welcome. Please contact: Branch Manager, Communication and Media Branch, Department of Social Services. Phone: 1300 653 227. Email: [email protected] Notice identifying other material or rights in this publication: 1. Australian Commonwealth Coat of Arms — not Licensed under Creative Commons, see https://www.itsanhonour.gov.au/coat-arms/index.cfm 2. Certain images and photographs (as marked) — not licensed under Creative Commons Annual Deregulation Report 2014 Department of Social Services Foreword The Australian Government’s deregulation agenda is a key Government priority. The Government continues to deliver on its commitment to cut unnecessary red tape, and I am proud that the Department of Social Services has made a strong contribution to this agenda in its first year. In 2014, the Department has benefited individuals and a range of business and community sectors by removing unnecessary red tape. We have abolished the National Gambling Regulator, which removed considerable Commonwealth duplication of state and territory government gambling regulatory responsibilities.