Connecting Marine Ecotourism Values in Northern Vancouver Island with Marine Protected Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

British Columbia Regional Guide Cat

National Marine Weather Guide British Columbia Regional Guide Cat. No. En56-240/3-2015E-PDF 978-1-100-25953-6 Terms of Usage Information contained in this publication or product may be reproduced, in part or in whole, and by any means, for personal or public non-commercial purposes, without charge or further permission, unless otherwise specified. You are asked to: • Exercise due diligence in ensuring the accuracy of the materials reproduced; • Indicate both the complete title of the materials reproduced, as well as the author organization; and • Indicate that the reproduction is a copy of an official work that is published by the Government of Canada and that the reproduction has not been produced in affiliation with or with the endorsement of the Government of Canada. Commercial reproduction and distribution is prohibited except with written permission from the author. For more information, please contact Environment Canada’s Inquiry Centre at 1-800-668-6767 (in Canada only) or 819-997-2800 or email to [email protected]. Disclaimer: Her Majesty is not responsible for the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in the reproduced material. Her Majesty shall at all times be indemnified and held harmless against any and all claims whatsoever arising out of negligence or other fault in the use of the information contained in this publication or product. Photo credits Cover Left: Chris Gibbons Cover Center: Chris Gibbons Cover Right: Ed Goski Page I: Ed Goski Page II: top left - Chris Gibbons, top right - Matt MacDonald, bottom - André Besson Page VI: Chris Gibbons Page 1: Chris Gibbons Page 5: Lisa West Page 8: Matt MacDonald Page 13: André Besson Page 15: Chris Gibbons Page 42: Lisa West Page 49: Chris Gibbons Page 119: Lisa West Page 138: Matt MacDonald Page 142: Matt MacDonald Acknowledgments Without the works of Owen Lange, this chapter would not have been possible. -

3LMANUSCRIPT REPORT SERIES No. 36

DFO - L bra y MPOBibio heque II 1 111111 11 11 11 V I 1 120235441 3LMANUSCRIPT REPORT SERIES No. 36 Some If:eat/viz& 3,5,unamia, Olt the Yacific ettadt of South and ✓ cuith anwitica, T. S. Murty, S. 0. Wigen and R. Chawla Marine Sciences Directorate 975 Department of the Environment, Ottawa Marine Sciences Directorate Manuscript. Report Series No. 36 SOME FEATURES OF TSUNAMIS ON THE PACIFIC COAST OF SOUTH AND NORTH AM ERICA . 5 . Molly S . O. Wigen and R. Chawla 1975 Published by Publie par Environment Environnement Canada Canada I' Fisheries and Service des !Aches Marine Service et des sciences de la mer Office of the Editor Bureau du fiedacteur 116 Lisgar, Ottawa K1 A Of13 1 Preface This paper is to be published in Spanish in the Proceedings of the Tsunami Committee XVII Meeting, Lima, Peru 20-31 Aug. 1973, under the International Association of Seismology and Physics of the Earth Interior. 2 Table of Contents Page Abstract - Resume 5 1. Introduction 7 2. Resonance characteristics of sonic inlets on the Pacific Coast of Soulh and North America 13 3. Secondary undulations 25 4. Tsunami forerunner 33 5. Initial withdrawal of water 33 6. Conclusions 35 7. References 37 3 4 i Abstract In order to investigate the response of inlets to tsunamis, the resonance characteristics of some inlets on the coast of Chile have been deduced through simple analytical considerations. A comparison is made with the inlets of southeast Alaska, the mainland coast of British Columbia and Vancouver Island. It is shown that the general level of intensif yy of secondary undulations is highest for Vancouver Island inlets, and least for those of Chile and Alaska. -

1967, Al and Frances Randall and Ramona Hammerly

The Mountaineer I L � I The Mountaineer 1968 Cover photo: Mt. Baker from Table Mt. Bob and Ira Spring Entered as second-class matter, April 8, 1922, at Post Office, Seattle, Wash., under the Act of March 3, 1879. Published monthly and semi-monthly during March and April by The Mountaineers, P.O. Box 122, Seattle, Washington, 98111. Clubroom is at 719Y2 Pike Street, Seattle. Subscription price monthly Bulletin and Annual, $5.00 per year. The Mountaineers To explore and study the mountains, forests, and watercourses of the Northwest; To gather into permanent form the history and traditions of this region; To preserve by the encouragement of protective legislation or otherwise the natural beauty of North west America; To make expeditions into these regions m fulfill ment of the above purposes; To encourage a spirit of good fellowship among all lovers of outdoor life. EDITORIAL STAFF Betty Manning, Editor, Geraldine Chybinski, Margaret Fickeisen, Kay Oelhizer, Alice Thorn Material and photographs should be submitted to The Mountaineers, P.O. Box 122, Seattle, Washington 98111, before November 1, 1968, for consideration. Photographs must be 5x7 glossy prints, bearing caption and photographer's name on back. The Mountaineer Climbing Code A climbing party of three is the minimum, unless adequate support is available who have knowledge that the climb is in progress. On crevassed glaciers, two rope teams are recommended. Carry at all times the clothing, food and equipment necessary. Rope up on all exposed places and for all glacier travel. Keep the party together, and obey the leader or majority rule. Never climb beyond your ability and knowledge. -

Northisle Copper and Gold Inc

Ministry of Energy, Mines & Petroleum Resources Mining & Minerals Division Assessment Report BC Geological Survey Title Page and Summary TYPE OF REPORT [type of survey(s)]: Archaeological Impact Assessment TOTAL COST: $14,254 AUTHOR(S): Morgan Bartlett, Robbin Chatan, Konstantin Lesnikov SIGNATURE(S): NOTICE OF WORK PERMIT NUMBER(S)/DATE(S): MX-8-271 / December 22, 2011 YEAR OF WORK: 2012 STATEMENT OF WORK - CASH PAYMENTS EVENT NUMBER(S)/DATE(S): 5421553 PROPERTY NAME: Island Copper East Block CLAIM NAME(S) (on which the work was done): Mo 4, Mo 5 COMMODITIES SOUGHT: N/A MINERAL INVENTORY MINFILE NUMBER(S), IF KNOWN: 092L 273 MINING DIVISION: Nanaimo NTS/BCGS: 092L/11 / 92L.054 o '" o '" LATITUDE: -127 22 21 LONGITUDE: 50 35 18 (at centre of work) OWNER(S): 1) NorthIsle Copper and Gold Inc. 2) MAILING ADDRESS: #2050-1111 West Georgia Street Vancouver BC V6E 4M3 OPERATOR(S) [who paid for the work]: 1) 2) MAILING ADDRESS: PROPERTY GEOLOGY KEYWORDS (lithology, age, stratigraphy, structure, alteration, mineralization, size and attitude): Bonanza Volcanics, Quatsino Formation, Karmutsen Formation, Island Plutonic Suite, porphyritic granitoid rocks, granodiorite, andesite, basalt, limestone, Upper Triassic, middle Jurassic, Island Copper Mine REFERENCES TO PREVIOUS ASSESSMENT WORK AND ASSESSMENT REPORT NUMBERS: AR 2659, 1681, 14393, 15884, 15707, 11460, 15024, 15077, 15367, 16510, 15024, 15077, 15367, 16510, 17368, 32722 Next Page TYPE OF WORK IN EXTENT OF WORK ON WHICH CLAIMS PROJECT COSTS THIS REPORT (IN METRIC UNITS) APPORTIONED (incl. support) -

Jennifer Galloway's 2010 Paper

Marine Micropaleontology 75 (2010) 62–78 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Marine Micropaleontology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/marmicro Research paper A high-resolution marine palynological record from the central mainland coast of British Columbia, Canada: Evidence for a mid-late Holocene dry climate interval Jennifer M. Galloway a,⁎, Lameed O. Babalola a, R. Timothy Patterson a, Helen M. Roe b a Ottawa-Carleton Geoscience Centre and Department of Earth Sciences, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada KIS 5B6 b School of Geography, Archaeology & Palaeoecology, Queen's University Belfast, Belfast, BT7 1NN, United Kingdom article info abstract Article history: Sediments collected in a 12-m long core (VEC02A04) obtained from Frederick Sound in the Seymour–Belize Received 24 December 2009 Inlet Complex of British Columbia were deposited between ca. 4540 cal. yr BP and ca. 1090 cal. yr BP in Received in revised form 6 March 2010 primarily dysoxic conditions. The sediments are characterized by alternating intervals of fine grained Accepted 8 March 2010 massive and laminated units. Laminated sediments consist of light-coloured diatom-rich layers deposited during summer and dark-coloured mineral-rich layers deposited during winter. Laminated sediments are Keywords: most common in portions of the core deposited between ca. 2840 cal. yr BP and ca. 1820 cal. yr BP, and Climate change correspond to a decline in the relative abundance and pollen accumulation rate of Cupressaceae pollen Late Holocene Coastal Western Hemlock biogeoclimatic between ca. 3190 cal. yr BP and ca. 2250 cal. yr BP. The preservation of laminated units and decline of zone Cupressaceae pollen at this time suggest that a drier and possibly cooler climate punctuated otherwise wet Marine palynology and temperate late Holocene conditions in the Seymour–Belize Inlet Complex. -

CHS Index Chart

Fisheries and Oceans Pi'lches et Oceans Canada Canada Canada ••• 137 ° 136 " 134" 133 ° 131° 129 ° ,.. 126 ° 125 " 124 " 123° 122° 119° 124 ° 118 ° GENERAL CHARTS CARTES GENERALES SMALL-CRAFT CHARTS REV ILLAG IGEDO LARGER SCALE CHARTS ISLAND CARTES POUR EMBARCATIONS CARTES A PLUS GRANDE ECHELLE 3050 Kootenay Lake and Rovet 75 000 3311 Sunshtno Coast- Vancouver Ha rbour lo/A 3052 Okanagan Lako so 000 Desolatoon Sound 40 000 3053 Shuswap Lake so 000 331:2 JerviS Intel ond/et Do•o latoon Sound 0 305S Waneta to /~ Hugh Keen leyside Dam 20 000 Vo,ous Scolo•JEche tle• vo"h• > z 3056 Hugh Koon loySido Dam to/A Burlon 40 000 3313 Gull Islands and Ad jacent Watotways/el les Vo1es Navigables Ad1acentes ~ ' 3057 Button IO/~ 1\rrowhood 40 000 Variou• Scale•/Echel le• vo"~"' 3058 Arrowhead lo/6 Rovo lotoko Go «m• 20 000 3488 Fro5er River/F I&uve Fraser, Cre•<ent l5land 3061 " "'"'on Lake and/ol Hamson R1ver '""'' to/~ Hon loon Mills 20 000 Harrison Lake 40 000 3469 Fraser Rovor/Fiouve Fr8set, Pattullo B"dgo Harrison R1ver 30 000 to/a Crescent Is land 20 000 Pitt River and/ot Poll l ak e 25 000 Stuaot L a~e (Not•howniP••rnd•qu o!) 50 000 54 " ~f--- ' ~ 0 "" I < ''"0' 't)Go iUn "?1- Cocoov• 3053 Foo ..o<o o l 0 "' GJ ,. Shu wap .•. Lake CANAOA !'; "'""""'' •·o~ d 130" 125° 120 " •5"omouo .,cocho Cceo> ,... ,. ' GJ ... ' <om l oops ~ DIXON E'N TRANCE' LEGENO/LEGENDE • •• • Scales smaller ttlan 1"40 000 Ectlellas plus petites qua 1:40 000 '' GJ Scales 1:40 000 and larger Ectlelles 1: 40 000 et plus grande& CHART SCALE Chart soale os the rat10 of one umt of d1stance 011 the cha" to the actual d.stance on the Earth's surface expressed on tho same unots. -

Climate Change and Decadal to Centennial-Scale Periodicities Recorded in a Late Holocene NE Pacific Marine Record: Examining the Role of Solar Forcing

Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology 386 (2013) 669–689 Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/palaeo Climate change and decadal to centennial-scale periodicities recorded in a late Holocene NE Pacific marine record: Examining the role of solar forcing J.M. Galloway a,⁎, A. Wigston a, R.T. Patterson a, G.T. Swindles b, E. Reinhardt c, H.M. Roe d a Department of Earth Sciences and Ottawa Geoscience Centre, Carleton University, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, Ontario K1S 5B6, Canada b School of Geography, University of Leeds, Leeds LS2 9JT, United Kingdom c School of Geography and Earth Sciences, McMaster University, Hamilton, ON L8S 4K1, Canada d School of Geography, Archaeology and Palaeoecology, Queen's University Belfast, Belfast BT7 1NN, United Kingdom article info abstract Article history: We present a decadal-scale late Holocene climate record based on diatoms, biogenic silica, and grain size Received 29 November 2012 from a 12-m sediment core (VEC02A04) obtained from Frederick Sound in the Seymour-Belize Inlet Complex Received in revised form 21 June 2013 of British Columbia, Canada. Sediments are characterized by graded, massive, and laminated intervals. Accepted 22 June 2013 Laminated intervals are most common between c. 2948–2708 cal. yr BP and c. 1992–1727 cal. yr BP. Available online 4 July 2013 Increased preservation of laminated sediments and diatom assemblage changes at this time suggest that cli- mate became moderately drier and cooler relative to the preceding and succeeding intervals. Spectral and Keywords: fi Late Holocene wavelet analyses are used to test for statistically signi cant periodicities in time series of proxies of primary Climate change production (total diatom abundance, biogenic silica) and hydrology (grain size) preserved in the Frederick Diatoms Sound record. -

Five Easy Pieces on the Strait of Georgia – Reflections on the Historical Geography of the North Salish Sea

FIVE EASY PIECES ON THE STRAIT OF GEORGIA – REFLECTIONS ON THE HISTORICAL GEOGRAPHY OF THE NORTH SALISH SEA by HOWARD MACDONALD STEWART B.A., Simon Fraser University, 1975 M.Sc., York University, 1980 A THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE AND POSTDOCTORAL STUDIES (Geography) THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA (Vancouver) October 2014 © Howard Macdonald Stewart, 2014 Abstract This study presents five parallel, interwoven histories of evolving relations between humans and the rest of nature around the Strait of Georgia or North Salish Sea between the 1850s and the 1980s. Together they comprise a complex but coherent portrait of Canada’s most heavily populated coastal zone. Home to about 10% of Canada’s contemporary population, the region defined by this inland sea has been greatly influenced by its relations with the Strait, which is itself the focus of a number of escalating struggles between stakeholders. This study was motivated by a conviction that understanding this region and the sea at the centre of it, the struggles and their stakeholders, requires understanding of at least these five key elements of the Strait’s modern history. Drawing on a range of archival and secondary sources, the study depicts the Strait in relation to human movement, the Strait as a locus for colonial dispossession of indigenous people, the Strait as a multi-faceted resource mine, the Strait as a valuable waste dump and the Strait as a place for recreation / re-creation. Each of these five dimensions of the Strait’s history was most prominent at a different point in the overall period considered and constantly changing relations among the five narratives are an important focus of the analysis. -

REC-EWED by APR 1 1,2009 J

PROSPECTING ASSESSMENT REPORT ON THE SEYMOUR INLET PROJECT (WIGWAM CLAIMS, Tenure # 572620 & 572621) (Pt/Os/Rh/lr ALASKAN TYPE INTRUSION) Seymour Inlet, Vancouver Mining Division NTS 92 M/2 (92M.017) Latitude 51°08'19", Longitude: 126°43'48" REC-EWED By APR 1 1,2009 J. T. ~Ihearer, M.Sc., P.Geo. Gold Commissioner's MfM5' - 2330 Tyner Street VANCOUVER, B.C. Port Coquitlam, BC !fJ r V3C 221 ;;e; ~~ • Phone:604-970-6402 ~ 1:1 I, ,j E-mail: [email protected] ~ [,! ,1 ~ri' " ("-I For § [~, l;j /2,. , i &-1' ...; ~,. "< ", Homegold Resources ltd /O-'"iI! c.":'/ v c' Unit 5 - 2330 Tyner Street t: £; ~ c«( Port Coquitlam, BC v c .. ~';.".;;- "'" V3C 221 ~J September 15, 2008 Fieldwork completed between August 1, 2008 and August 30, 2008 r- • TABLE of CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 PROPERTy 2 LOCATION, ACCESS and TOPOGRAPHY : 3 HISTORY and DEVELOPMENT 4 REGIONAL GEOLOGY 5 LOCAL GEOLOGy 6 ROCK DESCRIPTIONS 7 2008 PROSPECTING and GEOLOGY 9 CONCLUSIONS and RECOMMENDATIONS 10 ESTIMATE of COSTS for FUTURE WORK 11 STATEMENT of QUALIFICATIONS 12 REFERENCES 13 APPENDICES Appendix I Statement of Costs 14 Appendix II List of Specimens 15 Appendix III Titaniferous Zoned Pt-OZ-Rh/lr Vadadium Deposit Model And Magmatic Oxide Deposit Model 17 Prospecting Report on the Seymour Inlet Project (Wigwam Claims) September 15, 2008 Page ii • LIST of ILLUSTRATIONS and TABLES Following Page FIGURE 1 Property Location, 1":190km ii FIGURE 2 Detail Property Location 1 FIGURE 3 Claim Location Map, 1:51,000 2 FIGURE 4 Regional Geology Map, 1:147,869 4 FIGURE 5 Local Geology, 1:50,000 5 FIGURE 6 Local Prospecting Map, 1:10,000, Rainbow Creek Area 8 FIGURE 7 Local Prospecting Map, 1:10,000, Haig Bay Area 9 TABLES Page TABLE I List of Claims ! •••••••••••• 2 Prospecting Report on the Seymour Inlet Project (Wigwam Claims) September 15, 2008 Page iii ----------------~-------- pW INTRODUCTION The Wigwam Project is located near the head of Seymour Inlet, BC, a narrow coastal mainland fjord 85km east of the north tip of Vancouver Island in the Vancouver Mining Division. -

Postglacial Vegetation and Climate Dynamics in the Seymour-Belize Inlet Complex, Central Coastal British Columbia, Canada: Palynological Evidence from Tiny Lake

Postglacial vegetation and climate dynamics in the Seymour-Belize Inlet Complex, central coastal British Columbia, Canada: palynological evidence from Tiny Lake. Galloway, J. M., Doherty, C. T., Patterson, R. T., & Roe, H. (2009). Postglacial vegetation and climate dynamics in the Seymour-Belize Inlet Complex, central coastal British Columbia, Canada: palynological evidence from Tiny Lake. Journal of Quaternary Science, 24(4), 322-335. https://doi.org/10.1002/jqs.1232 Published in: Journal of Quaternary Science Document Version: Early version, also known as pre-print Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:23. Sep. 2021 JOURNAL OF QUATERNARY SCIENCE (2009) 24(4) 322–335 Copyright ß 2008 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Published online 23 October 2008 in Wiley InterScience (www.interscience.wiley.com) DOI: 10.1002/jqs.1232 Postglacial vegetation and climate dynamics in the Seymour-Belize Inlet Complex, central coastal British Columbia, Canada: palynological evidence from Tiny Lake JENNIFER M. -

Official Community Plan Background Report

VILLAGE OF SAYWARD OFFICIAL COMMUNITY PLAN BACKGROUND REPORT DRAFT PREPARED FOR: Village of Sayward 652-A H’Kusam Way PO Box 29 Sayward BC V0P 1R0 REPORT CONTACT Urban Systems Ltd. 290A England Ave Courtenay, BC V9N 6L6 File No. 2906.0003.01 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 Demographics and Population ............................................................................................................................. 4 2.1 Current Conditions Current ................................................................................................................................ 4 2.2 Key Planning Considerations ............................................................................................................................. 6 3.0 Community Participation .......................................................................................................................................... 8 3.1 Current Conditions ................................................................................................................................................... 8 3.2 Current Initiatives ...................................................................................................................................................... 11 3.3 Key Planning Consideration ............................................................................................................................. -

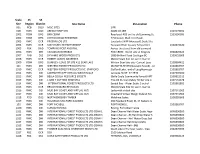

Scale Site SS Region SS District Site Name SS Location Phone

Scale SS SS Site Region District Site Name SS Location Phone 001 RCB DQU MISC SITES SIFR 01B RWC DQC ABFAM TEMP SITE SAME AS 1BB 2505574201 1001 ROM DPG BKB CEDAR Road past 4G3 on the old Lamming Ce 2505690096 1002 ROM DPG JOHN DUNCAN RESIDENCE 7750 Lower Mud river Road. 1003 RWC DCR PROBYN LOG LTD. Located at WFP Menzies#1 Scale Site 1004 RWC DCR MATCHLEE LTD PARTNERSHIP Tsowwin River estuary Tahsis Inlet 2502872120 1005 RSK DND TOMPKINS POST AND RAIL Across the street from old corwood 1006 RWC DNI CANADIAN OVERSEAS FOG CREEK - North side of King Isla 6046820425 1007 RKB DSE DYNAMIC WOOD PRODUCTS 1839 Brilliant Road Castlegar BC 2503653669 1008 RWC DCR ROBERT (ANDY) ANDERSEN Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1009 ROM DPG DUNKLEY- LEASE OF SITE 411 BEAR LAKE Winton Bear lake site- Current Leas 2509984421 101 RWC DNI WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. MAHATTA RIVER (Quatsino Sound) - Lo 2502863767 1010 RWC DCR WESTERN FOREST PRODUCTS INC. STAFFORD Stafford Lake , end of Loughborough 2502863767 1011 RWC DSI LADYSMITH WFP VIRTUAL WEIGH SCALE Latitude 48 59' 57.79"N 2507204200 1012 RWC DNI BELLA COOLA RESOURCE SOCIETY (Bella Coola Community Forest) VIRT 2509822515 1013 RWC DSI L AND Y CUTTING EDGE MILL The old Duncan Valley Timber site o 2507151678 1014 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD Sandal Bay - Water Scale. 2 out of 2502861881 1015 RWC DCR BRUCE EDWARD REYNOLDS Mobile Scale Site for use in marine 1016 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Ladysmith virtual site 2507541962 1017 RWC DSI MUD BAY COASTLAND VIRTUAL W/S Coastland Virtual Weigh Scale at Mu 2507541962 1018 RTO DOS NORTH ENDERBY TIMBER Malakwa Scales 2508389668 1019 RWC DSI HAULBACK MILLYARD GALIANO 200 Haulback Road, DL 14 Galiano Is 102 RWC DNI PORT MCNEILL PORT MCNEILL 2502863767 1020 RWC DSI KURUCZ ROVING Roving, Port Alberni area 1021 RWC DNI INTERNATIONAL FOREST PRODUCTS LTD-DEAN 1 Dean Channel Heli Water Scale.