Patrick Cary and His Italian Poems

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Una Rete Di Protezione Intorno a Caravaggio E a Carlo Gesualdo Rei Di Omicidio E La Storica Chiesa Di San Carlo Borromeo Ad Avellino

Sinestesieonline PERIODICO QUADRIMESTRALE DI STUDI SULLA LETTERATURA E LE ARTI SUPPLEMENTO DELLA RIVISTA «SINESTESIE» ISSN 2280-6849 UNA RETE DI PROTEZIONE INTORNO A CARAVAGGIO E A CARLO GESUALDO REI DI OMICIDIO E LA STORICA CHIESA DI SAN CARLO BORROMEO AD AVELLINO Riccardo Sica Abstract Il saggio ricostruisce, su basi il più possibile documentarie, una probabile rete di protezione creatasi nel 1607 intorno a Caravaggio a Napoli e a Carlo Gesualdo sotto la regia occulta del cardinale Federico Borromeo (nei rapporti intercorsi specialmente tra il Cardinale Ferdinando Gonzaga, l’arcivescovo Luigi De Franchis, il cardinale Francesco Maria Del Monte e Costanza Colonna) e ricerca gli effetti di ripercussione di tale rete nella suggestiva e complessa storia della Chiesa di San Carlo Borromeo ad Avellino, quasi un simbolo della cultura borromaica e della Controriforma sancarliana ad Avellino ed in Irpinia dal XVII al XIX secolo. Tale storia, specialmente relativamente alla edificazione e alla distruzione della chiesa, per tanti versi parallela e talora simile a quella di ben più note chiese dedicate a San Carlo in Italia (a Milano e a Cave principalmente), coinvolge famiglie, non solo locali, potenti come i Colonna (in particolar modo la Principessa donna Antonia Spinola, moglie del Principe Caracciolo di Avellino), i Borromeo, i Gesualdo, gli Altavilla di Acquaviva d’Aragona, i Caracciolo, ed artisti della cerchia borromaica del Seicento come i Nuvolone, Figino, G.C. Procaccini, sfiorando lo stesso Caravaggio. Parole chiave Contatti Caravaggio, Flagellazione, rete di protezione, [email protected] Ferdinando Gonzaga, Luigi De Franchis, Francesco Maria Del Monte, Costanza Colonna, Chiesa di San Carlo Borromeo, Ospedale dei Fatebenefratelli, Carlo Gesualdo, Controriforma, molinismo, Colonna, Borromeo, Caracciolo, Principessa Antonia Spinola Colonna, pittori, Nuvolone, G.C. -

Scheda Di Angela Groppi Su Lucrezia Barberini D'este

Notizie dalle sale di studio Scheda di Angela Groppi su Lucrezia Barberini d’Este Nome: Angela Groppi Nazionalità: italiana Domicilio/ Università: Sapienza - Università di Roma e.mail: [email protected] Titolo accademico: professore associato (storia moderna) Progetto: pubblicazione Titolo: Lucrezia Barberini d’Este. Una donna malinconica del Seicento La ricerca relativa a Lucrezia Barberini d’Este (1632-1699) è parte di uno studio più ampio volto a indagare le strategie di riscatto messe in opera dai Barberini dopo la fuga in Francia (1645-1646) a seguito della persecuzione attuata nei loro confronti da Innocenzo X. Strategie in cui la rete dei parenti, degli amici, dei «fedeli servitori», che agirono per loro conto oltralpe e in Italia fu fondamentale per rientrare nel favore della monarchia francese e di Mazzarino, così come per riconciliarsi con il pontefice, negoziare il rientro in Italia e riconquistare la reputazione perduta. I reticoli sociali «micropolitici» - sostanziati dai rapporti di clientela, di parentela, di amicizia, di patronage... - sono ormai da anni al centro dell’interesse della storiografia internazionale volta a indagare le tecniche di governo e di potere nell’ambito delle monarchie europee di età moderna. In questo contesto la centralità delle alleanze matrimoniali nelle strategie di ascesa e di consolidamento dei gruppi familiari ha assunto nuovo risalto; inoltre, grazie anche agli apporti della storiografia di genere, è stato possibile evidenziare il ruolo centrale delle donne negli affari di famiglia. Entrando a far parte di un nuovo gruppo familiare esse erano infatti il tramite di strategie e di aggregazioni parentali utili ad accrescere onore e prestigio del casato; così come a stabilire connessioni ramificate in grado di ampliare l’area delle protezioni e delle alleanze. -

The Theater of Piety: Sacred Operas for the Barberini Family In

The Theater of Piety: Sacred Operas for the Barberini Family (Rome, 1632-1643) Virginia Christy Lamothe A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2009 Approved by: Tim Carter, chair Annegret Fauser Anne MacNeil John Nádas Jocelyn Neal © 2009 Virginia Christy Lamothe ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii Abstract Virginia Christy Lamothe: “The Theater of Piety: Sacred Operas for the Barberini Family (Rome, 1632-1643)” (Under the direction of Tim Carter) In a time of religious war, plague, and reformation, Pope Urban VIII and his cardinal- nephews Antonio and Francesco Barberini sought to establish the authority of the Catholic Church by inspiring audiences of Rome with visions of the heroic deeds of saints. One way in which they did this was by commissioning operas based on the lives of saints from the poet Giulio Rospigliosi (later Pope Clement IX), and papal musicians Stefano Landi and Virgilio Mazzocchi. Aside from the merit of providing an in-depth look at four of these little-known works, Sant’Alessio (1632, 1634), Santi Didimo e Teodora (1635), San Bonifatio (1638), and Sant’Eustachio (1643), this dissertation also discusses how these operas reveal changing ideas of faith, civic pride, death and salvation, education, and the role of women during the first half of the seventeenth century. The analysis of the music and the drama stems from studies of the surviving manuscript scores, libretti, payment records and letters about the first performances. -

Panegírico a Taddeo Barberini (1631)

BIBLIOTECA DIGITAL – PROYECTO ARELPH LAS ARTES DEL ELOGIO: POESÍA, RETÓRICA E HISTORIA EN LOS PANEGÍRICOS HISPANOS GABRIEL DE CORRAL Panegírico a Taddeo Barberini (1631) Edición de Jesús Ponce Cárdenas PANEGIRICOS.COM 2017 GABRIEL DE CORRAL – Panegírico a Taddeo Barberini – PROYECTO ARELPH – PANEGIRICOS.COM ÍNDICE 3 APES URBANAE: INTRODUCCIÓN A UN PANEGÍRICO ROMANO 35 PANEGÍRICO A TADDEO BARBERINI 39 APÉNDICE: LOS SONETOS DE GABRIEL DE CORRAL EN ELOGIO DE LA CASA BARBERINI - 2 - GABRIEL DE CORRAL – Panegírico a Taddeo Barberini – PROYECTO ARELPH – PANEGIRICOS.COM APES URBANAE: INTRODUCCIÓN A UN PANEGÍRICO ROMANO La obra de Gabriel del Corral (Valladolid, 1588-Toro, 1646) abarca una rica variedad de géneros y formas, que van desde la novela cortesana hasta la poesía jocosa de academia, pasando por la escritura encomiástica, el teatro palaciego o las relaciones de sucesos. Pese al manifiesto interés que presentan los textos de este poeta barroco, la crítica no se ha detenido en trazar debidamente su perfil biográfico y literario. Con la intención de paliar esa llamativa laguna en los estudios áureos, abordamos el estudio y edición del panegírico en octavas reales que el autor castellano compuso y editó en Roma en 1631. La dilucidación de dicho texto laudatorio hace necesaria una indagación previa en torno a varios elementos significativos en la trayectoria vital y literaria de un ingenio aún mal conocido1. Por ese motivo, el estudio preliminar se articulará en cuatro partes netamente diferenciadas. En primer lugar se abordará el examen de diversas claves biográficas, a la luz de nuevos datos documentales. Seguidamente se estudiará la valoración que se hace de este autor en dos famosos compendios eruditos entre 1630 y 1633, coincidiendo con su estancia en Roma. -

The Landscapes of Gaspard Dughet: Artistic Identity and Intellectual Formation in Seventeenth-Century Rome

ABSTRACT Title of Document: THE LANDSCAPES OF GASPARD DUGHET: ARTISTIC IDENTITY AND INTELLECTUAL FORMATION IN SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ROME Sarah Beth Cantor, Doctor of Philosophy, 2013 Directed By: Professor Anthony Colantuono, Department of Art History and Archaeology The paintings of Gaspard Dughet (1615-1675), an artist whose work evokes the countryside around Rome, profoundly affected the representation of landscape until the early twentieth century. Despite his impact on the development of landscape painting, Dughet is recognized today as the brother-in-law of Nicolas Poussin rather than for his own contribution to the history of art. His paintings are generally classified as decorative works without subjects that embody no higher intellectual pursuits. This dissertation proposes that Dughet did, in fact, represent complex ideals and literary concepts within his paintings, engaging with the pastoral genre, ideas on spirituality expressed through landscape, and the examination of ancient Roman art. My study considers Dughet’s work in the context of seventeenth-century literature and antiquarian culture through a new reading of his paintings. I locate his work within the expanding discourse on the rhetorical nature of seventeenth-century art, exploring questions on the meaning and interpretation of landscape imagery in Rome. For artists and patrons in Italy, landscape painting was tied to notions of cultural identity and history, particularly for elite Roman families. Through a comprehensive examination of Dughet’s paintings and frescoes commissioned by noble families, this dissertation reveals the motivations and intentions of both the artist and his patrons. The dissertation addresses the correlation between Dughet’s paintings and the concept of the pastoral, the literary genre that began in ancient Greece and Rome and which became widely popular in the early seventeenth century. -

L'oratorio Aquilano Nel Secondo Seicento

UNIVERSITÀ DEGLI STUDI DI UDINE Dipartimento di Storia e tutela dei beni culturali Dottorato di ricerca in Storia: culture e strutture delle aree di frontiera XXVI ciclo TESI DI DOTTORATO L’Oratorio aquilano nel secondo Seicento: echi quietisti, condanne, relazioni. Coordinatore Relatore Bruno FIGLIUOLO Flavio RURALE Dottorando Stefano Boero ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- Udine, 2013 1 L’Oratorio aquilano nel secondo Seicento: relazioni, condanne, echi quietisti Indice Premessa p. 5 Introduzione p. 7 1. La Biografia di Giambattista Magnante: rapporti tra Jesi, Roma e p. 17 L’Aquila 1.1. Tommaso Baldassini e la Congregazione dell’Oratorio di Jesi p. 17 1.2. Pier Matteo Petrucci: rapporti con l’Oratorio aquilano p. 23 1.3. La dedica al cardinale Alderano Cybo p. 31 1.4. L’autore Nicolò Balducci p. 35 1.5. Il libro sulle missioni del Magnante p. 40 1.5.1. Il Magnante nel contesto oratoriano delle Marche p. 40 1.5.2. La fondazione della Congregazione di Osimo p. 43 1.5.3. Gli oratoriani e il quietismo nelle Marche del Seicento p. 48 2. Testi, letture e atteggiamenti nell’Oratorio aquilano intorno alla metà del p. 53 Seicento 2.1. Il Perito medico spirituale p. 53 2.1.1. La cura d’anime come «medicina» p. 53 2.1.2 Il niente e l’annichilazione p. 58 2.2. L’usura fatta lecita nel Banco di carità sotto la protettione di S. Anna p. 62 2.2.1. Il Banco di carità e l’usura p. 62 2.2.2. La procura dentro e fuori il banco p. 68 2.3. -

Download (11Mb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/90103 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications 1 Scenography at the Barberini court in Rome: 1628-1656 by Leila Zammar A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Warwick Renaissance Studies Centre for the Study of the Renaissance 2 Table of contents List of Abbreviations…………………………………………................ p. 4 List of Illustrations………………………………………………..……. p. 5 Acknowledgements……………………………………………………... p. 10 Abstract…………………………………………………………………. p. 12 Introduction…………………………………………………………….. p. 13 Chapter 1 New light on early performances (August 1628 and Carnival of 1632)……………………………………….. p. 36 Il contrasto di Apollo con Marsia: August 1628……....... p. 41 Il Sant’Alessio: Carnival 1632…………………………... p. 51 Chapter 2 Operas staged with the collaboration of Francesco Guitti (1633-1634)……………………………………… p. 62 Erminia sul Giordano (Carnival 1633)…………………. p. 64 Il Sant’Alessio (Carnival 1634)…………………………. p. 88 Chapter 3 Further developments (1635-1638)………………..…… p. 120 I Santi Didimo e Teodora (Carnivals 1635 and 1636)…... p. 123 La pazzia d’Orlando and San Bonifacio (Carnival 1638)... p. 145 Chapter 4 Inaugurating the newly-built theatre (1639 and 1642). p. 163 The Teatro Barberini from its construction to its demolition (1637-1932)…………………………………. -

Photograph: Museo Archeologico Nazionale Di Palestrina Nome Del

Nome del monumento: Palazzo Barberini (Museo Archeologico Nazionale) Ubicazione: Piazza della Cortina 00036 Palestrina Roma, Palestrina, Roma, Italia Datazione del monumento: 1630-1660 Tipologia: Palazzo feudale Promotore(i) della costruzione: Taddeo Barberini (1603, Roma – 1647, Parigi), Prefetto di Photograph: Museo Archeologico Nazionale di Roma, e il figlio Maffeo (1630-1685), nato dal matrimonio con Palestrina Anna Colonna Storia: Il palazzo e l’intero feudo di Palestrina, di proprietà del principe Francesco Colonna di antica famiglia feudale, fu acquistato nel 1630 da papa Urbano VIII (1623-1644) per donarlo al fratello Carlo Barberini. La famiglia, originaria di Barberino in Val d’Elsa, era costituita da piccoli proprietari terrieri poi mercanti stabilitisi inizialmente a Firenze e nel corso del 500 con il primo prelato Francesco (1528-1600) anche a Roma. A Taddeo Barberini, figlio di Carlo morto in quello stesso 1630, si devono la risistemazione e la sopraelevazione del palazzo che corona la sommità dell’altura sulle cui pendici sorgeva lo scenografico santuario del II secolo a.C. dedicato alla Fortuna Primigenia, famoso nell’antichità per i suoi oracoli. Il Palazzo dopo i bombardamenti dell’ultima guerra - che hanno riportato in luce alcune strutture antiche - è stato donato allo Stato nel 1956 ed adibito a Museo Archeologico Nazionale. Descrizione: Il palazzo è contraddistinto dalla coincidenza tra strutture antiche - il concavo doppio portico anulare terminale del santuario, del quale sono visibili nel pavimento dell’ingresso le basi delle colonne – e le fasi costruttive che si sono sovrapposte dall’alto Medioevo fino ai Barberini. L’iscrizione del portale principale, datata 1498, e lo stemma dei Colonna sul pozzo testimoniano gli ingenti lavori commissionati dai Colonna che hanno dato al palazzo, attraverso la scala centrale a due rampe nella cavea e la sistemazione del pozzo, una connotazione urbanistica di assialità dell’intero complesso e di fusione tra le strutture antiche e moderne. -

Informanon Ta USERS

INFORMAnON Ta USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, sorne thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be tram any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction Is depend.nt upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. ln the unlikely avent that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and lhere are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had ta be removed, a note will indicate the detetion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reprocluced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left·hand corner and continuing from 18ft te right in equal sections with small overlaps. Photographs înduded in the original manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6- x 9- black and white photographie prints are available for any photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contad UMI directly te arder. ProQuest Information and leaming 300 North leeb Raad, Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 USA 800-521-0600 THE BARBERlNl AND THE NEW CHRISTIAN EMPIRE :A STUDY OF THE HISTORY OF CONSTANfINETAPESTRIES BY PŒTRO DA CORTONA BY EUSA SHARI GARFINKLE DEPARTMENT OF ART mSTORY MCGILL UNIVERSITY, MONTREAL NOVEMBER, 1999 A THESIS -

Versus New: Colonna Art Patronage During the Barberini and Pamphilj Pontificates (1623-1655)

Originalveröffentlichung in: Burke, Jill ; Bury, Michael (Hrsgg.): Art and identity in early 7 modern Rome, Aldershot 2008, S. 135-154 Old Nobility versus New: Colonna Art Patronage during the Barberini and Pamphilj Pontificates (1623-1655) Christina Strunck One of the characteristics of Roman 'court culture' was the powerful social dynamic created by its celibate oligarchy: again and again, men from relatively obscure families were appointed cardinals and rose to a rank almost equal to that of kings;1 again and again, popes helped the secular members of their family attain high positions in society. The Congregatio super executione mandatorum contra Barones Status Ecclesiastici (founded in 1596) enabled the papal families to purchase the often heavily indebted feudal states of the ancient nobility, thereby also acquiring the noble titles that went with them.2 Since social status had to be maintained by conspicuous consumption, the old Roman nobility found it increasingly difficult to keep pace with the papal families, who could rely on the near-endless resources of the papal treasury. The present study seeks to show how this situation was dealt with by the Colonna, who considered themselves to be Rome's 'First Family'. In the introduction 1 will discuss the basis for this claim and the factors that defined the Colonna's relationship to the papacy. I will then proceed to analyse the self-representation of the Colonna di Paliano, the main branch of the family in the seventeenth century, focusing on works of art and literature which defined Colonna identity by emphasizing the family's collaboration or conflict with the pope.3 The chosen time-frame is particularly interesting because the Colonna's relationship to the pope changed drastically after the conclave of 1644 While they had maintained close contacts with Urban VIII Barberini (1623-44), they found themselves in icy isolation under his successor Innocent X Pamphilj (1644-55). -

A Chiesa Di Santa Rosalia Nel Palazzo Dei Principi Barberini a Palestrina: Committenza E Cantiere

DOI 10.17401/STUDIERICERCHE-2/2017-MARCONI-ERAMO a chiesa di Santa Rosalia nel palazzo deiL principi Barberini a Palestrina: committenza e cantiere NICOLETTA MARCONI, ELENA ERAMO Università degli Studi “Tor Vergata”, Roma “Alto Natal ti dié Preneste amica, Somma gloria, e splendor Tu rendi a quella, Compensando così l’onor Paterno” (1) Il 22 luglio 1737, per ordine del cardinale Francesco Barberini juniore (1662- 1738), Valentino Consalvi “intagliatore di legname in Roma” riceveva un pa- gamento di 80 scudi per aver realizzato a tutte sue “spese, robba, e manifat- (1) Leonardo Cecconi, Storia di Palestrina, città del prisco Lazio tura […], dui Coretti di Legno per servizio da collocarsi nella Chiesa di Santa (Ascoli, per Nicola Ricci,1756), 8. (2) Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana (BAV), Archivio Barberini, Giu- Rosalia della Città di Palestrina”, eseguiti “a forma del disegno dell’Architetto stificazioni I, vol. 512, ricevuta 41. Questo saggio costituisce di Sua Eminenza [Tommaso de Marchis, 1693-1759] e secondo il modelletto una prima sintesi di uno studio monografico di prossima pubbli- fattone sopra detto Disegno”.(2) Qualche mese più tardi, il 2 novembre 1737, il cazione. Si ringraziano il Dott. Luigi Cacciaglia per il fondamen- battiloro Giuseppe Cattani veniva retribuito per la fornitura di 20 libretti d’oro tale aiuto nelle ricerche e il Principe Don Benedetto Barberini impiegati “per dorare li cornicioni” della medesima chiesa.(3) Si compiva così per l’accesso all’edificio. (3) BAV, Arch. Barb., Giust. I, vol. 512, ricevuta 103-104. l’esecuzione del prezioso corredo decorativo della chiesa dei Barberini nella (4) Nel gennaio 1630 Carlo Barberini (1562-1630) acquistò da dimora prenestina. -

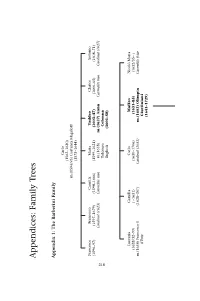

Appendices: Family T Rees

Appendices: Family Trees Appendix 1: The Barberini Family Carlo (1562–1630) m.(1594/95) Costanza Magalotti (1575–1644) Francesco Francesco Camilla Maria Taddeo Clarice Antonio (1596–97) (1597–1679) (1598–1666) (1599–1621) (1603–47) (1606–65) (1608–71) 218 Cardinal (1623) Carmelite nun m.(1618) m.(1627) Anna Carmelite nun Cardinal (1627) Tolomeo Colonna Buglioli (1601–58) Lucrezia Camilla Carlo Maffeo Nicolò Maria (1628/32–99) ( –1631) (1630–1706) (1631–85) (1632/35– ) m.(1654) Francesco I (1628–30?) Cardinal (1653) m.(1653) Olimpia Carmelite friar d’Este Giustiniani (1641–1729) Costanza Camilla Francesco Urbano Taddeo (1657–87) (1660–1740) (1662–1738) (1664–1722) (1666–1702) m.(1681) Gaetano m.(1689) Cardinal (1690) m1.(1691) Cornelia Zeno m.(1701) Silvia Maria Grancesco Caetani Carlo Borromeo Ottoboni Teresa Muti di Arona ( –1691) (1675–1711) m2.(1693) Felice Ventimiglia e Pignatelli ( –1709) widow of Biagio Ventimiglia m3.(1713) Maria Teresa Boncompagni Ludovisi (1692–1744) Ruggero Cornelia Costanza Maffeo Callisto (1699–1704) (1716–97) (1688– ) m.(1728) Giulio Cesare Colonna illegit. from Apollonia de Angelis not recognized by the family and expelled from the house 219 Appendix 2: The Boncompagni & Boncompagni Ludovisi Families 220 Gregorio (1590–1628) m.(1607) Leonor Zapata y Brancia (1593–1679) Giacomo Ugo Giovanni Costanza Michele Caterina Maria Girolamo Cecelia (1613–36) (1614–76) Battista (1616–48) (1618–39) (1619–99) (1620–48) (1622–84) (1624–1706) m.(1641) (1615–16) m.(1640) Nun, S.Marta a Nun, S.Marta a Cardinal Nun, S.Marta