Cinema in Post-Taliban Afghanistan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Annual Report and Accounts 2004/2005

THE BFI PRESENTSANNUAL REPORT AND ACCOUNTS 2004/2005 WWW.BFI.ORG.UK The bfi annual report 2004-2005 2 The British Film Institute at a glance 4 Director’s foreword 9 The bfi’s cultural commitment 13 Governors’ report 13 – 20 Reaching out (13) What you saw (13) Big screen, little screen (14) bfi online (14) Working with our partners (15) Where you saw it (16) Big, bigger, biggest (16) Accessibility (18) Festivals (19) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Reaching out 22 – 25 Looking after the past to enrich the future (24) Consciousness raising (25) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Film and TV heritage 26 – 27 Archive Spectacular The Mitchell & Kenyon Collection 28 – 31 Lifelong learning (30) Best practice (30) bfi National Library (30) Sight & Sound (31) bfi Publishing (31) Looking forward: Aims for 2005–2006 Lifelong learning 32 – 35 About the bfi (33) Summary of legal objectives (33) Partnerships and collaborations 36 – 42 How the bfi is governed (37) Governors (37/38) Methods of appointment (39) Organisational structure (40) Statement of Governors’ responsibilities (41) bfi Executive (42) Risk management statement 43 – 54 Financial review (44) Statement of financial activities (45) Consolidated and charity balance sheets (46) Consolidated cash flow statement (47) Reference details (52) Independent auditors’ report 55 – 74 Appendices The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The bfi annual report 2004-2005 The British Film Institute at a glance What we do How we did: The British Film .4 million Up 46% People saw a film distributed Visits to -

FFF Osama SG

Osama Study Guide Alicia McGivern fresh film festival 2005 1 Osama Osama Introduction Questions dir. Siddaq Barmak/ Osama is a film about life for a young Mulan is another film where the Afghanistan-Netherlands-Japan-Ireland- girl under Taliban rule in Afghanistan, central character must change her Iran/83mins/2003 the home of director and writer, Siddiq identity in order to survive. Do you Barmak. Said to be the first film know this film? Describe the story Cast produced in the country since this and compare with Osama. Marina Golbahari Osama extreme religious regime was ousted in Can you think of any other films in Arif Herati Espandi 2002, it premiered at Cannes in 2003 which the central character has to Zubaida Sahar Mother and went on to win a Golden Globe for change their identity? Best Foreign Film in 2004. The film What do you know about Afghanistan? Other cast opens with a quote from Nelson Brainstorm with your class. Mohamad NadUer Khadjeh Mandela - ‘I cannot forget, but I will Mohamad Haref Harati forgive’, which serves to entice the Director Gol Rahman Ghorbandi viewer to speculate on the story as Siddiq Barmak’s filmmaking career Khwaja Nader well as suggest an indictment of the can be seen as a reflection of recent Hamida Refah system on which the story is based. Afghan history. His early interest in The film tells the story of a cinema began in the Park Cinema in Production young girl who has to reinvent herself Kabul. Some 30 years later he Production Designer Akbar Meshkini in order to survive. -

Film & Event Calendar

1 SAT 17 MON 21 FRI 25 TUE 29 SAT Events & Programs Film & Event Calendar 12:00 Event 4:00 Film 1:30 Film 11:00 Event 10:20 Family Gallery Sessions Tours for Fours: Art-Making Warm Up. MoMA PS1 Sympathy for The Keys of the #ArtSpeaks. Tours for Fours. Daily, 11:30 a.m. & 1:30 p.m. Materials the Devil. T1 Kingdom. T2 Museum galleries Education & 4:00 Film Museum galleries Saturdays & Sundays, Sep 15–30, Research Building See How They Fall. 7:00 Film 7:00 Film 4:30 Film 10:20–11:15 a.m. Join us for conversations and T2 An Evening with Dragonfly Eyes. T2 Dragonfly Eyes. T2 10:20 Family Education & Research Building activities that offer insightful and Yvonne Rainer. T2 A Closer Look for 7:00 Film 7:30 Film 7:00 Film unusual ways to engage with art. Look, listen, and share ideas TUE FRI MON SAT Kids. Education & A Self-Made Hero. 7:00 Film The Wind Will Carry Pig. T2 while you explore art through Research Building Limited to 25 participants T2 4 7 10 15 A Moment of Us. T1 movement, drawing, and more. 7:00 Film 1:30 Film 4:00 Film 10:20 Family Innocence. T1 4:00 Film WED Art Lab: Nature For kids age four and adult companions. SUN Dheepan. T2 Brigham Young. T2 This Can’t Happen Tours for Fours. SAT The Pear Tree. T2 Free tickets are distributed on a 26 Daily. Education & Research first-come, first-served basis at Here/High Tension. -

Armanshahr-23-24-En.Pdf (

A periodical on human rights and civil society Special issue on women 4th Year, Issues 23-24, April 2012 Website: http://armanshahropenasia.wordpress.com/ E-mail: [email protected] Facebook: [email protected] Facebook Armanshahr Publishing: https://www.facebook.com/groups/Armanshahr.Publishing Armanshahr Foundation Armanshahr Foundation is an independent, not for profit citizen organisation based in Kabul and is not affiliated with any economic, political, religious, ethnic, groups or governments. The Foundation’s mission is to create proper forums to ensure citizen social demand for democracy, human rights, justice and rule of law and to create through cultural manifestations and publications a broad constituency of well-in- formed citizens. Armanshahr Foundation also actively promotes reflection and debate both inside Afghanistan, trans-regionally and internationally with the goal of ensuring solidarity, progress and safeguarding peace. This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. The contents of the document can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union. Some of the items and articles that are published in each issue of “Armanshahr” from other sources are intended to inform our readers, but their contents or positions do not necessarily reflect Armanshahr’s positions. Armanshahr, a periodical on human rights and civil society Issues 23-24 (Year IV) – On Women April 2012 Circulation: 20,000 All rights are reserved -

Presentación De Powerpoint

F I L M S E R I E S The Immigrant Experience in English ASSOCIACIÓ DE PROFESSORS DEPARTAMENT D’ANGLÈS D’ANGLÈS DE LES ILLES BALEARS DE L’EOI DE PALMA APABAL and the Department of English of the Palma EOI are pleased to present four films with immigration - related themes during the January 2013 time frame. WHEN Wednesday, 9 January 2013 Wednesday, 16 January 2013 Wednesday, 23 January 2013 Wednesday, 30 January 2013 WHAT TIME 18.00 h. WHERE “Sa Nostra Cultural Centre”, c/ Concepció 12. Tel. 971 72 52 10 The films will be in the original English, with subtitles. * Attendance is free. Coordinator: Assumpta Sureda Film Moderators: Carol Williams, Michael Carroll, James Miele and Armando Fernández. More Information: www.apabal.com [email protected] January 9 (Wednesday) 18.00 h. THE TERMINAL (2004) An eastern immigrant finds himself stranded in JFK airport, and must take up temporary residence there. Director: Steven Spielberg Writers: Andrew Niccol (story), Sacha Gervasi (story). Stars: Tom Hanks, Catherine Zeta-Jones and Chi McBride. FILM MODERATOR: Carol Willliams January 16 (Wednesday) 18.00 h BEND IT LIKE BECKHAM (2002) The daughter of orthodox Sikh rebels against her parents' traditionalism by running off to Germany with a football team (soccer in America). Director: Gurinder Chadha. Writers:, Gurinder Chadha, Guljit Bindra. Stars: Parminder Nagra, Kheira Knightley and Jonathan RyesMeyers. FILM MODERATOR: Michael Carroll January 23 (Wednesday) 18.00 h MY BEAUTIFUL LAUNDERETTE (1985) Only recommended to people over 16. An ambitious Asian Briton and his white lover strive for success and hope, when they open up a glamorous laundromat. -

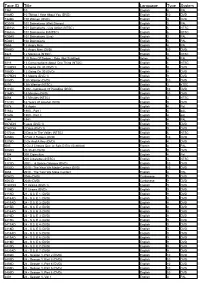

Tape ID Title Language Type System

Tape ID Title Language Type System 1361 10 English 4 PAL 1089D 10 Things I Hate About You (DVD) English 10 DVD 7326D 100 Women (DVD) English 9 DVD KD019 101 Dalmatians (Walt Disney) English 3 PAL 0361sn 101 Dalmatians - Live Action (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 0362sn 101 Dalmatians II (NTSC) English 6 NTSC KD040 101 Dalmations (Live) English 3 PAL KD041 102 Dalmatians English 3 PAL 0665 12 Angry Men English 4 PAL 0044D 12 Angry Men (DVD) English 10 DVD 6826 12 Monkeys (NTSC) English 3 NTSC i031 120 Days Of Sodom - Salo (Not Subtitled) Italian 4 PAL 6016 13 Conversations About One Thing (NTSC) English 1 NTSC 0189DN 13 Going On 30 (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 7080D 13 Going On 30 (DVD) English 9 DVD 0179DN 13 Moons (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 3050D 13th Warrior (DVD) English 10 DVD 6291 13th Warrior (NTSC) English 3 nTSC 5172D 1492 - Conquest Of Paradise (DVD) English 10 DVD 3165D 15 Minutes (DVD) English 10 DVD 6568 15 Minutes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 7122D 16 Years Of Alcohol (DVD) English 9 DVD 1078 18 Again English 4 Pal 5163a 1900 - Part I English 4 pAL 5163b 1900 - Part II English 4 pAL 1244 1941 English 4 PAL 0072DN 1Love (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0141DN 2 Days (DVD 1) English 9 DVD 0172sn 2 Days In The Valley (NTSC) English 6 NTSC 3256D 2 Fast 2 Furious (DVD) English 10 DVD 5276D 2 Gs And A Key (DVD) English 4 DVD f085 2 Ou 3 Choses Que Je Sais D Elle (Subtitled) French 4 PAL X059D 20 30 40 (DVD) English 9 DVD 1304 200 Cigarettes English 4 Pal 6474 200 Cigarettes (NTSC) English 3 NTSC 3172D 2001 - A Space Odyssey (DVD) English 10 DVD 3032D 2010 - The Year -

FIRST CENTURY AVANT-GARDE FILM RUTH NOVACZEK a Thesis

NEW VERNACULARS AND FEMININE ECRITURE; TWENTY- FIRST CENTURY AVANT-GARDE FILM RUTH NOVACZEK A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of Westminster for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2015 Acknowledgements Thanks to Chris Kraus, Eileen Myles and Rachel Garfield for boosting my morale in times of great uncertainty. To my supervisors Michael Mazière and Rosie Thomas for rigorous critique and sound advice. To Jelena Stojkovic, Alisa Lebow and Basak Ertur for camaraderie and encouragement. To my father Alfred for support. To Lucy Harris and Sophie Mayer for excellent editorial consultancy. To Anya Lewin, Gillian Wylde, Cathy Gelbin, Mark Pringle and Helen Pritchard who helped a lot one way or another. And to all the filmmakers, writers, artists and poets who make this work what it is. Abstract New Vernaculars and Feminine Ecriture; Twenty First Century Avant-Garde Film. Ruth Novaczek This practice-based research project explores the parameters of – and aims to construct – a new film language for a feminine écriture within a twenty first century avant-garde practice. My two films, Radio and The New World, together with my contextualising thesis, ask how new vernaculars might construct subjectivity in the contemporary moment. Both films draw on classical and independent cinema to revisit the remix in a feminist context. Using appropriated and live-action footage the five short films that comprise Radio are collaged and subjective, representing an imagined world of short, chaptered ‘songs’ inside a radio set. The New World also uses both live-action and found footage to inscribe a feminist transnational world, in which the narrative is continuous and its trajectory bridges, rather than juxtaposes, the stories it tells. -

Quantum of Solace De Marc Forster Pierre Barrette

Document generated on 09/28/2021 5:22 p.m. 24 images Quantum of Solace de Marc Forster Pierre Barrette Comédie Number 140, December 2008, January 2009 URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/25257ac See table of contents Publisher(s) 24/30 I/S ISSN 0707-9389 (print) 1923-5097 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this review Barrette, P. (2008). Review of [Quantum of Solace de Marc Forster]. 24 images, (140), 60–60. Tous droits réservés © 24/30 I/S, 2008 This document is protected by copyright law. Use of the services of Érudit (including reproduction) is subject to its terms and conditions, which can be viewed online. https://apropos.erudit.org/en/users/policy-on-use/ This article is disseminated and preserved by Érudit. Érudit is a non-profit inter-university consortium of the Université de Montréal, Université Laval, and the Université du Québec à Montréal. Its mission is to promote and disseminate research. https://www.erudit.org/en/ W. d'Oliver Stone figure paternelle, George juxtaposition d'événements réels soigneuse Jr est donc en quête per ment choisis suffisant à en déterminer une pétuelle d'une reconnais interprétation univoque. Quant au reste, sance qui, à ses yeux, ne Stone se fait portraitiste et livre son verdict viendra jamais. sur l'entourage de ce président faiblard : Dick Pour faire ce portrait, W. Cheney est la sombre eminence grise qui télé raconte essentiellement guide les décisions, Karl Rove une immonde la deuxième moitié du créature rampante, Condoleeza Rice une premier mandat du pré bourgeoise dédaigneuse, Donald Rumsfeld sident, c'est-à-dire que un dangereux imbécile, Paul Wolfowitz une Stone se concentre sur les quantité négligeable et Colin Powell la seule événements entourant la personne sensée au milieu de cette poignée 1/1/ peut être vu comme un double de décision d'envahir l'Irak, truffant son récit d'illuminés. -

Pessuto Kelen M.Pdf

ii UNIVERSIDADE ESTADUAL DE CAMPINAS INSTITUTO DE ARTES KELEN PESSUTO O ‘ESPELHO MÁGICO’ DO CINEMA IRANIANO: UMA ANÁLISE DAS PERFORMANCES DOS “NÃO” ATORES NOS FILMES DE ARTE Dissertação apresentada ao Instituto de Artes, da Universidade Estadual de Campinas, para obtenção do Título de Mestre em Artes. Área de concentração: Artes Cênicas. Orientadora: Profª. Drª. Francirosy Campos Barbosa Ferreira CAMPINAS 2011 iii . . . . . . .. iv v vi Dedico essa dissertação à memória dos meus pais, Agueda e José Pessuto, que são os espelhos da minha vida. À minha sobrinha Gabriela, por existir e fazer a minha vida mais feliz. À minha orientadora e amiga Francirosy C. B. Ferreira, por tanta afeição e apoio. vii viii AGRADECIMENTOS À Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo (FAPESP), pelo financiamento desta pesquisa, que permitiu minha dedicação exclusiva e o acesso ao material. Agradeço também aos pareceristas, que acreditaram no projeto. À minha mãe Agueda Pessuto, que tanto incentivou minha carreira, que fez sacrifícios enormes para que eu me formasse, tanto no teatro, quanto na faculdade. Sempre expressou sua admiração e carinho. Muito amiga e companheira, que mesmo não estando presente entre nós, é o guia da minha vida. Espero ser um por cento do que ela foi. Nunca me esqueço que horas antes dela morrer, pediu para eu ler menos e dar mais atenção para ela, não cumpri o que pediu... No dia seguinte à sua morte ocorreu o exame para ingressar no mestrado. Passar foi uma questão de honra para mim. Eis que termino essa pesquisa e lhe agradeço, pois se não fosse esse exemplo de mulher batalhadora no qual me inspiro, não teria conseguido. -

Kandahar Av Mohsen Makhmalbaf Iran 2001, 85 Minuter Nafas Är En

Kandahar av Mohsen Makhmalbaf Iran 2001, 85 minuter Nafas är en ung journalist från Afghanistan som lever i exil i Kanada. Hon får ett desperat brev från sin syster som fortfarande är kvar i Afghanistan och som planerar att ta sitt liv under den åstundande solförmörkelsen. Hon ger sig genast av mot Kandahar för att rädda sin syster. Hon reser till Iran, och därifrån måste hon bege sig över gränsen. Som ensam kvinna kan hon inte ta sig någonstans, och under resans gång får hon hjälp av fyra guider, som på olika sätt representerar det talibanska förtrycket; en äldre flykting från Afghanistan, en liten pojke som blivit relegerad från koranskolan, en svart amerikan som arbetar som läkare i öknen och en enarmad man som skadats av en landmina. Bakgrund För några år sedan blev den iranske regissören Mohsen Makhmalbaf uppsökt av en afghansk kvinna bosatt i Kanada. Niloufar Pazira hoppades att han skulle ha kontakter som kunde hjälpa henne att ta sig över gränsen till sitt forna hemland. Ärendet brådskade eftersom brevet som föranlett hennes avresa avslöjade att väninnan i Afghanistan var på väg att ta sitt liv. Niloufar Pazira släpptes aldrig in i Afghanistan och tvingades återvända till Kanada. Även om Mohsen Makhmalbaf inte hade kunnat hjälpa henne hade han svårt att släppa hennes historia. Han intresserade sig så mycket för den att han började studera och undersöka Afghanistan i skrifter, böcker och dokumentärfilmer. Något år senare sökte han upp Niloufar Pazira för att erbjuda henne huvudrollen i den film som skulle ta avstamp i hennes berättelse. Mohsen Makhmalbaf talar om Afghanistan som ”landet utan bilder”. -

A Rare Glimpse of Tahereh's Face in Through the Olive Trees

A rare glimpse of Tahereh’s face in Through the Olive Trees (Zire darakhatan zeyton) (dir. Abbas Kiarostami, France/ Iran, 1994). Courtesy Artifi cial Eye Women in a Widening Frame: (Cross-)Cultural Projection, Spectatorship, and Iranian Cinema Lindsey Moore This article addresses the entwined issues of gendered and cul- tural representation in contemporary Iranian cinema. One of the remarkable features of recent Iranian film is its allegorical use of gendered tropes, in particular the (in)visibility and (im)mobility of women in social space. The female body, which has been defined in historically charged and culturally assertive terms, is constantly reinvested thematically and technically. In Iran, as in more conventionally “postcolonial” sites of knowledge produc- tion,1 the relationship between vision and embodied, gendered objects is both culturally specificand informed by cross-cultural encounter. This article urges continued attention to the import of female representation in relation to a film’s reception both within and outside of the national viewing context. I assess the implications of verisimilitude in three films: Abbas Kiarostami’s Through the Olive Trees (Zire darakhatan zeyton) (France/Iran, 1994), Samira Makhmalbaf’s The Apple (Sib) (Iran/ France, 1998), and Kim Longinotto and Ziba Mir-Hosseini’s Copyright © 2005 by Camera Obscura Camera Obscura 59, Volume 20, Number 2 Published by Duke University Press 1 2 • Camera Obscura Divorce Iranian Style (UK, 1998). The difficulty in generically categorizing these films, particularly the latter two, rests on the exploitation in each case of the hinge between documentary and dramatic technique. It is my intention not only to contextualize this strategy in relation to postrevolutionary Iranian cultural politics, but to investigate the effects of generically hybrid texts that enter the international sphere. -

The Open Image: Poetic Realism and the New Iranian Cinema

Downloaded from The open image: poetic realism and the New Iranian Cinema http://screen.oxfordjournals.org/ SHOHINI CHAUDHURI and HOWARD FINN When Mohsen Makhmalbaf's Safar e Ghandehar/Kandahar was screened at London's Institute for Contemporary Arts in Autumn at Senate House Library, University of London on December 4, 2015 2001 it drew sell-out audiences, as it did in other European and North American cities. The film's success, partly due to its timely release, also reflects an enthusiasm internationally for Iranian films which has been gathering momentum in recent years. This essay focuses on one characteristic of 'New Iranian Cinema' which has evidently intrigued both critics and audiences, namely the foregrounding of a certain type of ambiguous, epiphanic image. We attempt to explore these images, which we have chosen - very simply - to call 'open images". One might read these images directly in terms of the political and cultural climate of the Islamic Republic which engendered them, as part of the broader ongoing critical debate on the relationship of these films to contemporary Iranian social reality Our intention, however, is primarily to draw structural and aesthetic comparisons across different national cinemas, to show, among other things, how a repressed political dimension returns within the ostensibly apolitical aesthetic form of the open image. The term "image' encompasses shot, frame and scene, and includes sound components - open images may deploy any of these elements. Open images are not necessarily extraordinary images, they often belong to the order of the everyday. While watching a film one may meet them with some resistance - yet they have the property of producing virtual after-images in the mind.