Respondents 25 Sca 001378

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Thomas Voeckler

Thomas Voeckler Informations Ti -Blanc 1,2 Surnom Francis 3 22 juin 1979 (38 ans) Naissance Schiltigheim Nationalité Français Équipe a ctuelle Direct Énergie 4 Spécialité Puncheur Équipes amateurs 1999 Vendée U 2000 Vendée U-Pays de la Loire Équipes professionnelles 09.2000-12.2000 Bonjour-Toupargel (stagiaire) 2001-2002 Bonjour 2003-2004 Brioches La Boulangère 2005-2008 Bouygues Telecom 2009-2010 BBox Bouygues Telecom 2011-2015 Europcar 2016-2017 Direct Énergie Principales victoires 2 championnats Champion de France sur route 2004 et 2010 Classiques Grand Prix de Plouay 2007 Grand Prix cycliste de Québec 2010 1 classement annexe de grand tour Meilleur grimpeur du Tour de France 2012 4 étapes de grands tours Tour de France (4 étapes) Thomas Voeckler , né le 22 juin 1979 à Schiltigheim (Bas-Rhin), est un coureur cycliste français, professionnel de 2001 à 2017. Durant l'ensemble de sa carrière, Thomas Voeckler a été membre des équipes dirigées par Jean-René Bernaudeau , le dernier sponsor étant Direct Énergie. Il a notamment été champion de France sur route en 2004 et 2010, et vainqueur du Grand Prix de Plouay 2007 , du Grand Prix cycliste de Québec , de quatre étapes du Tour de France en 2009 , en 2010 et en 2012 . Il s'est rendu populaire lors du Tour de France 2004 en portant le maillot jaune pendant dix jours. Il réédite cet exploit lors du Tour de France 2011 , où il finit à la 4 e plac e du classement général. Il remporte le maillot de meilleur grimpeur du Tour de France 2012. Il prend sa retraite le 23 juillet 2017, à l'issue du Tour de France 2017. -

Armstrong.Pdf

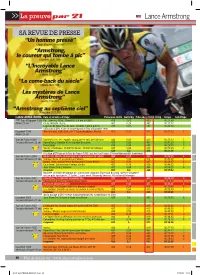

>> La preuve par 21 Lance Armstrong SA REVUE DE PRESSE “Un homme pressé” L’Equipe Magazine, 04.09.1993 “Armstrong, le coureur qui tombe à pic” L’Humanité, 05.07.1999 “L’Incroyable Lance Armstrong” L’Equipe, 12.07.1999 “Le come-back du siècle” L’Equipe, 26.07.1999 “Les mystères de Lance Armstrong” Le JDD, 27.06.2004 “Armstrong au septième ciel” Le Midi Libre, 25.07.2005 Lance ARMSTRONG Cols et victoires d’étape Puissance réelle watts/kg Puissance étalon 78 kg temps Cols Etape Tour Tour d’Espagne 1998 Pal. Jimenez 433w, 20min30s, 8,4 km à 6,49%, 418 5,65 400 00:21:49 4ème-27 ans Cerler. Montée courte. 462 6,24 442 00:11:33 Lagunas de Neila. Peu de vent, en forêt, 7 km à 8,57%, 415 5,61 397 00:22:18 Utilisation d’EPO et de cortisone durant le Tour d’Espagne 1998 Dauphiné 1999 Mont Ventoux CLM. ‘Battu de 1’1s par Vaughters. Record. 455 6,15 432 00:57:52 1 8ème-28 ans Tour de France 2004 La Mongie. 2ème derrière Basso 487 6,58 462 00:23:15 2 Tour de France 1999 Sestrières 1er. 1er «exploit» marquant en solo. Vent de face 448 6,05 420 00:27:13 5 1er puis déclassé-33 ans Beille 1er. En solitaire. 438 5,92 416 00:45:40 6 1er puis déclassé-28 ans Alpe d’Huez. Contrôle et se contente de suivre. 436 5,89 407 00:41:20 3 Chalimont 1er. Victoire à Villard de Lans 410 5,54 392 00:19:05 3 Piau Engaly 395 5,34 385 00:26:15 5 Alpe d’Huez CLM 1er. -

Organizational Forms in Professional Cycling – Efficiency Issues of the UCI Pro Tour

Organizational Forms in Professional Cycling – Efficiency Issues of the UCI Pro Tour Luca Rebeggiani§ * Davide Tondani DISCUSSION PAPER NO. 345 First Version: August 2006 This Version: July 2007 ISSN: 0949–9962 ABSTRACT: This paper gives a first economic approach to pro cycling and analyses the changes induced by the newly introduced UCI Pro Tour on the racing teams’ behaviour. We develop an oligopolistic model starting from the well known Cournot framework to analyse if the actual setting of the UCI Pro Tour leads to a partially unmeant behaviour of the racing teams. In particular, we show that the blamed regional concentration of their race participation depends on a lack of incentives stemming from the licence assignation procedure. Our theo- retical results are supported by empirical data concerning the performance of the racing teams in 2005 and 2006. As a recommendation for future improvements, we derive from the model the need for a relegation system for racing teams. ZUSAMMENFASSUNG: Der Aufsatz stellt die erste ökonomische Analyse des professionellen Radsports dar. Er analysiert insbesondere die Anreizwirkungen der neuen UCI Pro Tour auf Teams und Fahrer. Ausgehend von dem bekannten Cournot-Ansatz entwickeln wir ein einfaches Oligopol-Modell, um zu untersuchen, ob die der- zeitige Pro Tour-Organisation zu einem unerwünschten Verhalten der Teilnehmer führt. Wir zeigen, dass insbe- sondere das Problem der geographischen Konzentration der Rennteilnahmen der Teams von den mangelnden Anreizen abhängt, die vom jetzigen Lizenzvergabesystem ausgehen. Unsere theoretischen Ergebnisse werden durch empirische Daten aus der Pro Tour 2005 und 2006 gestützt. Als Empfehlung für zukünftige Entwicklun- gen leiten wir aus dem Modell die Notwendigkeit einer Öffnung der Pro Tour ab, mit Auf- und Abstiegsmög- lichkeiten für Rennteams. -

Sporting Legends: Axel Merckx

SPORTING LEGENDS: AXEL MERCKX SPORT: CYCLING COMPETITIVE ERA: 1993 - 2007 Axel Merckx (born August 8, 1972 in Uccle, Belgium), the son of the legendary Eddy Merckx, was a professional road bicycle racer since November 1993. In 1995 he joined Team Motorola as a team-mate of the young Lance Armstrong. Despite several strong years of racing, including winning the Belgian national championship in 2000, Axel is probably still more famous for being the son of five-time Tour de France champion Eddy Merckx than for any of his cycling exploits. Despite being overshadowed by his father's formidable record, Axel has repeatedly vowed to make his mark by accomplishing feats Eddy never managed - including a Tour de France stage win at the top of Alpe d'Huez and a win in the Paris-Tours World Cup race - but has yet to make good on these promises. He has a large number of fans in Belgium, and would undoubtedly engender a great deal more goodwill if he were ever to achieve either of those elusive wins. One place where he has overshadowed his father is at the Olympic Games. A good climber, Axel is probably at his best in the mid-altitude mountain ranges, notably the Massif Central and the Ardennes. His favorite race, and the one he feels best in, is Liège-Bastogne-Liège. He is also always aiming for a Tour de France stage win, and can often be found in long breaks. His sprinting capacities are not that strong, so he is often beaten at the finish. SPORTING LEGENDS: AXEL MERCKX Merckx enjoyed his 2004 Olympic Bronze success in Athens. -

Tdf 1996-2005.Pdf

Tour de France Top Overall Three Finishers Noting Anti-Doping Rule Violations and Allegations Year First Second Third 1996 Bjarne Riis on May 25, 2007 Riis issued a press release that he Jan Ullrich Implicated in Operación Puerto and was barred from the Richard Virenque On October 24, 2000, he admits in a also had made "mistakes" in the past, and in the following press 2006 Tour de France and fired by his T-Mobile team. He received a French court to doping knowingly but not willingly. The conference confessed to taking EPO, growth hormone and two-year suspension for Puerto involvement (8/22/11 – 8/21/13), Swiss cycling association suspended him for nine months cortisone for 5 years, from 1993 to 1998, including during his and results disqualified since 5/1/2005. victory in the 1996 Tour de France. 1997 Jan Ullrich Implicated in Operación Puerto and was barred from Richard Virenque On October 24, 2000, he admits in a French court Marco Pantani In the 1999 Giro d'Italia, he was expelled the 2006 Tour de France and fired by his T-Mobile team. He to doping knowingly but not willingly. The Swiss cycling association due to his irregular blood values. Although he was received a two-year suspension for Puerto involvement (8/22/11 suspended him for nine months disqualified for "health reasons", it was implied that – 8/21/13), and results disqualified since 5/1/2005. Pantani's high hematocrit was the product of EPO use. Later, it was revealed he had a hematocrit level of 60 per cent after his crash in 1995, above the later limit of 50. -

A Genealogy of Top Level Cycling Teams 1984-2016

This is a work in progress. Any feedback or corrections A GENEALOGY OF TOP LEVEL CYCLING TEAMS 1984-2016 Contact me on twitter @dimspace or email [email protected] This graphic attempts to trace the lineage of top level cycling teams that have competed in a Grand Tour since 1985. Teams are grouped by country, and then linked Based on movement of sponsors or team management. Will also include non-gt teams where they are “related” to GT participants. Note: Due to the large amount of conflicting information their will be errors. If you can contribute in any way, please contact me. Notes: 1986 saw a Polish National, and Soviet National team in the Vuelta Espana, and 1985 a Soviet Team in the Vuelta Graphics by DIM @dimspace Web, Updates and Sources: Velorooms.com/index.php?page=cyclinggenealogy REV 2.1.7 1984 added. Fagor (Spain) Mercier (France) Samoanotta Campagnolo (Italy) 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 Le Groupement Formed in January 1995, the team folded before the Tour de France, Their spot being given to AKI. Mosoca Agrigel-La Creuse-Fenioux Agrigel only existed for one season riding the 1996 Tour de France Eurocar ITAS Gilles Mas and several of the riders including Jacky Durant went to Casino Chazal Raider Mosoca Ag2r-La Mondiale Eurocar Chazal-Vetta-MBK Petit Casino Casino-AG2R Ag2r Vincent Lavenu created the Chazal team. -

22 Marzo 2015 • Sunday, 22Nd March 2015 293 Km Il “Festival Del Ciclismo” | the “Cycling Festival”

rzo 22 Ma 2015 OPS Milano_Sanremo 2015 no sponsor.indd 1 13/03/15 15:13 2 Domenica 22 Marzo 2015 • Sunday, 22nd March 2015 293 km Il “FESTIVAL DEL CICLISMO” | THE “CYCLING FESTIVAL” La Milano-Sanremo comincia con l’ultimo giorno d’inverno e finisce Milano-Sanremo starts on the last day of winter and ends on the first con il primo giorno di primavera, anche se piove o nevica, perché da day of spring, even in the rain or snow, because there are no transitional tempo non esistono più le mezze stagioni ma l’unica stagione sempre seasons only more, only the eternal present of a cycling season that is attuale è quella del ciclismo, che con il tempo si è allungata e allargata, longer and broader than ever, and once extended from Milano-Sanremo prima andava dalla Milano-Sanremo al Giro di Lombardia e adesso va to the the Giro d’Italia di Lombardia but now begins in Africa and ends dall’Africa alla Cina. in China. La Milano-Sanremo è la storia che abita la geografia ed è la geogra- Milano-Sanremo is history that inhabits geography, geography made fia che si umanizza nella storia, però è anche scienze, applicazioni human in history, but it is also applied science, technology, and a lot tecniche e moltissima educazione fisica, è italiano, che continua of physical education. It is Italian, which is still the language spoken a essere la lingua del gruppo, però è sempre francese e sempre più in the peloton, but it remains French, and is becoming increasingly inglese, è anche religione, tutti credenti nella bicicletta come simbolo English. -

«Io, Un Ragazzino Felice, in Giallo a Parigi»

/T Tra cinque giorni al via il 78° Giro di Francia. 3.900 chilometri, f qualche montagna in meno e una grossa novità: dopo 25 anni CICLISMO e tante delusioni i nostri ciclisti partono in pole position con Bugno ••••• e Chiappucci tra i favoriti. Ma fate attenzione a Greg Lemond Italiani in Tour Parte sabato prossimo da Lione il 78° Tour de Fran- ce. Uno dei più grandi avvenimenti sportivi, dopo le ; j^n Olimpiadi e i mondiali di calcio. L'anno scorso, alla tv, lo guardarono un miliardo di persone. Quest'an Chiappucci no 3900 km con qualche salita in meno. Dopo anni coccolata dalle miss di latitanze, gli italiani in pole position. Bugno e Protagonista a Chiappucci (l'anno scorso secondo) partono tra i sorpresa del favoriti con Lemond, Indurain, Delgado, Breukink. Tour dell'anno scorso (arrivò secondo) parte DARIO CICCAMLU anche quest'anno in •• Che stia arrivando lo sap- un'innovazione degli organiz iamo da tanti piccoli segnali zatori che. in questo modo, pole position E! bibite ghiacciate, l'aria con con la chiusura delle scuole, con Bugno e dizionata che ronza nell'uffi sperano di avere un ulteriore Lemond cio, le strade roventi e meno aumento di pubblico Qualche A destra trafficate, il fotocolor di miss altra cifra pnma della vera no Il percorso Riccione Fa caldo, un caldo vità Dunque si comincia sa bato 6 luglio a Lione e si f in isce del Tour '91 da Tour de France. e, sotto, Tour, che passione! Ogni domenica 28 a Parigi (natural anno, nel mese di luglio, lo ri mente). -

Ag2r Prevoyance

TEAMS YEAR OF TOUR NAME NAT BIRTH VICTORIES APPEARANCES AG2R PREVOYANCE MOREAU Christophe FRA 1971 20 11 ARRIETA José Luis SPA 1971 3 7 CALZATI Sylvain FRA 1979 2 3 FRANCE DEIGNAN Philip IRL 1983 1 0 DESSEL Cyril FRA 1974 5 3 Main sponsor: Provident fund and insurance company DION Renaud FRA 1978 1 0 Address: EUSRL France Cyclisme, Parc d’activités de Côte Rousse, DUMOULIN Samuel FRA 1980 10 4 DUPONT Hubert FRA 1980 0 0 73000 Chambéry le Haut, France ELMIGER Martin •N SWI 1978 6 1 Website: www.ag2r-cyclisme.com GADRET John FRA 1979 0 0 ProTour ranking (end 2006): 15th GERRANS Simon AUS 1980 9 2 2007 budget: ¤7 million GOUBERT Stéphane FRA 1970 0 7 Date of team’s foundation: 2000 KRIVTSOV Yuriy UKR 1979 5 3 Tour record: Eighth appearance, six stage victories LOUBET Julien FRA 1985 0 0 Past stars: Alexandre Botcharov, Andrei Kivilev, Christophe Agnolutto, MANDRI René •N EST 1984 0 0 Laurent Brochard, Jaan Kirsipuu, Francisco Mancebo MANGEL Laurent FRA 1981 1 0 Team manager: Vincent Lavenu MONDORY Lloyd FRA 1982 0 0 NAIBO Carl FRA 1982 3 0 NAVAS David SPA 1974 1 1 NAZON Jean-Patrick FRA 1977 21 4 NOCENTINI Rinaldo •N ITA 1977 10 1 BERNARD HINAULT’S ANALYSIS POULHIES Stéphane FRA 1985 0 0 “Evidently this team has both Cyril Dessel and RIBLON Christophe FRA 1981 1 0 ROUSSEAU Nicolas •N FRA 1983 0 0 Christophe Moreau, who are no doubt dreaming SONNERY Blaise •N FRA 1985 0 0 about doing as well as they did last year. -

Spitting in the Soup Mark Johnson

SPITTING IN THE SOUP INSIDE THE DIRTY GAME OF DOPING IN SPORTS MARK JOHNSON Copyright © 2016 by Mark Johnson All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or photocopy or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations within critical articles and reviews. 3002 Sterling Circle, Suite 100 Boulder, Colorado 80301-2338 USA (303) 440-0601 · Fax (303) 444-6788 · E-mail [email protected] Distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Publisher Services A Cataloging-in-Publication record for this book is available from the Library of Congress. ISBN 978-1-937715-27-4 For information on purchasing VeloPress books, please call (800) 811-4210, ext. 2138, or visit www.velopress.com. This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper). Art direction by Vicki Hopewell Cover: design by Andy Omel; concept by Mike Reisel; illustration by Jean-Francois Podevin Text set in Gotham and Melior 16 17 18 / 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 CONTENTS Introduction ...................................... 1 1 The Origins of Doping ............................ 7 2 Pierre de Coubertin and the Fair-Play Myth ...... 27 3 The Fall of Coubertin’s Ideal ..................... 41 4 The Hot Roman Day When Doping Became Bad ..................................... 55 5 Doping Becomes a Crime........................ 75 6 The Birth of the World Anti-Doping Agency ..... 85 7 Doping and the Cold War........................ 97 8 Anabolic Steroids: Sports as Sputnik .......... -

La Velta, Le Tour D'espagne Les Étapes 2015 Et Son Histoire

La Vuelta les étapes 2015 et son histoire Paru le 20 août 2015 Par la rédaction de l’écho de l’info LA VUELTA 2015 LES ÉTAPES À VENIR ET LE PROGRAMME + EXPLICATIONS Hors-série numéro 3 - LaVelta 01/08/2015 2 les étapes 2015 et son histoire QU’EST-CE-QUE C’EST QUE LA VUELTA ? Le Tour d'Espagne (Vuelta ciclista a España en espagnol) est une compétition cycliste à étapes dont la première édition a eu lieu en 1935, et disputée annuellement depuis 1955. C'est une compétition de trois semaines, disputée à la fin de l'été. Son trajet varie d'année en année et consiste en une vingtaine d'étapes totalisant environ 3 000 km. La dernière étape se termine traditionnellement à Madrid, la capitale. Le Tour d'Espagne est, avec le Tour d'Italie et le Tour de France, l'un des trois grands tours cyclistes. La Vuelta appartient aujourd'hui à la société Unipublic dont ASO possède 49 % des parts depuis juin 2008. LES DIFFÉRENTS MAILLOTS Classement général Le maillot rouge récompense le leader du classement général et donc au terme de l'épreuve le vainqueur de la Vuelta . Il est le maillot le plus prestigieux. Il a plusieurs fois changé de couleurs (jaune, orange, rouge ou encore blanc) avant de devenir rouge. Hors-série numéro 3 - LaVelta 01/08/2015 3 les étapes 2015 et son histoire Le classement par points Le maillot vert récompense le vainqueur du classement par points. Ce classement revient au coureur ayant remporté le plus de points lors des arrivées d'étapes, ainsi que lors des sprints intermédiaires. -

LIÈGE-BASTOGNE-LIÈGE (1892 - 2021 = 107E Édition) La Doyenne Créée Par Le R

4e Monument LIÈGE-BASTOGNE-LIÈGE (1892 - 2021 = 107e édition) La Doyenne Créée par le R. Persant CL (L’Express : → 1948 ; La Dernière-Heure : 1949 → ; Le Sportif 80) Année Vainqueur Second Troisième Quatrième Cinquième 1892 (29.05) Léon Houa (BEL) Léon Lhoest (BEL) Louis Rasquinet (BEL) Antoine Gehenniaux Henri Thanghe (BEL) 1 (BEL) 1893 (28.05) Léon Houa (BEL) Michel Borisowskik Charles Colette (BEL) Richard Fischer (BEL) Louis Rasquinet (BEL) 2 (BEL) 1894 (26.08) Léon Houa (BEL) Louis Rasquinet (BEL) René Nulens (BEL) Maurice Garin (ITA) Palau (BEL) 3 1895- Non disputée 1907 1908 (30.08) André Trousselier Alphonse Lauwers Henri Dubois (BEL) René Vandenberghe Georges Verbist (BEL) (FRA) (BEL) (BEL) 1909 (16.05) Victor Fastre (BEL) Eugène Charlier (BEL) Paul Deman (BEL) Félicien Salmon (BEL) Hector Tiberghien (BEL) 1910 Non disputée 1911 (12.06) Joseph Van Daele Armand Lenoir (BEL) Victor Kraenen (BEL) Auguste Benoit (BEL) Hubert Noël (BEL) (BEL) 1912 a Omer Verschoore Jacques Coomans André Blaise (BEL) François Dubois (BEL) Victor Fastre (BEL) (15.09) (BEL) (BEL) 1912 b . Jean Rossius 1er Alphonse Lauwers Cyrille Prégardien Walmer Molle (BEL) (15.09) (BEL) (BEL) (BEL) . Dieudonné Gauthy 1er (BEL) 1913 (06.07) Maurice Mortiz (BEL) Alphonse Fonson Hubert Noël (BEL) Omer Collignon (BEL) René Vermandel (BEL) (BEL) 1914- Non disputée 1918 1919 (28.09) Léon Devos (BEL) Henri Hanlet (BEL) Arthur Claerhout (BEL) Alphonse Van Heck Camille Leroy (BEL) (BEL) 1920 (06.06) Léon Scieur (BEL) Lucien Buysse (BEL) Jacques Coomans Léon Despontins (BEL)