A Queen-Mother at Work: on Handan Sultan and Her Regency During the Early Reign of Ahmed I*

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

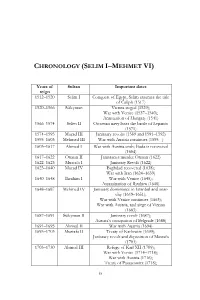

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

Animal Welfare and the Protection of Draft Animals in the Ottoman Fatwa¯ Literature and Legislation

religions Article Be Gentle to Them: Animal Welfare and the Protection of Draft Animals in the Ottoman Fatwa¯ Literature and Legislation Necmettin Kızılkaya Faculty of Divinity, Istanbul University, 34452 Istanbul,˙ Turkey; [email protected] Received: 5 August 2020; Accepted: 16 October 2020; Published: 20 October 2020 Abstract: Animal studies in the Islamic context have greatly increased in number in recent years. These studies mostly examine the subject of animal treatment through the two main sources of Islam, namely, the Qur’an and the traditions of the Prophet Muhammad. Some studies that go beyond these two sources examine the subject of animal treatment through the texts of various disciplines, especially those of Islamic jurisprudence and law. Although these two research approaches offer a picture of how animal treatment is perceived in Islamic civilization, it is still not a full one. Other sources, such as fatwa¯ books and archive documents, should be used to fill in the gaps. By incorporating these into the pool of research, we will be better enabled to understand how the principles expressed in the main sources of Islam are reflected in daily life. In this article, I shall examine animal welfare and ( animal protection in the Ottoman context based on the fataw¯ a¯ of Shaykh al-Islam¯ Ebu’s-Su¯ ud¯ Efendi and archival documents. Keywords: animal welfare; animal protection; draft animals; Ottoman Legislation; Fatwa;¯ Ebussuud¯ Efendi In addition to the foundational sources of Islam and the main texts of various disciplines, the use of fatwa¯ (plural: fataw¯ a¯) collections and archival documents will shed light on an accurate understanding of Muslim societies’ perspectives on animals. -

Nahil Ve Nakıl Alayları

NAHIL VE NAKIL ALAYLARI Ord. Prof. ISMAIL HAKKI UZUNÇAR~ILI Nahirin manas~~ hurma a~ac~~ demek olup galat olarak Nak~ l diye me~hur olmu~tur. Nahilbent denilen üstadlar taraf~ndan a~aç, meyve, çiçek ve hayvan ~ekilleri yap~larak dü~ünlerde gelinin önünde götürülen muhtelif boydaki nahillere dair Osmanl~~ tarihlerinde ve sûrnamelerde bilgi vard~ r. Te~bih yoliyle meyvesi ve çiçe~i çok a~aca (pürnak~l) denilir. Dü~ünlerde erkek taraf~ ndan tertip edilen nahil, lügatlerde birbirlerine benzer ~ekillerde tarif edilmektedir. Ahteri'de nahil, palmiye yâni hurma a~ac~d~ r. Biyanki, nahil'in palmiye denilen a~aç ve kad~ nlar~n bir nevi ziynet e~yas~~ oldu~unu yaz~yor. Lehce-i Osmanr de nahil, galat~~ nak~l, mumdan ve gümü~ten a~aç dal~~ res- mi ki arûs (gelin) önünde giderdi. Salal~ i kamusunda hurma a~ac~~ ve eski zamanda balmumundan veya gümü~ten mahsusen yap~larak gelinin önünde götürülen meyve ve ~üld~fe (çiçek) yi hav": ve k~y- metli ta~larla süslü a~aca ~tlak olunurdu, demektedir. Burhan- ~~ Kat ~~ <nahilbendi târif ederken: "Ol kimsedir ki mum- dan a~aç ve meyve suretleri imM eyliye. Hâlâ o surette nahil, mu- harrefi nak~l tabir ederler" diyor. Gülistan ~erhinde S û d i merhum, "Nahil, Türkide tahrif edüp nak~l dedikleridir. Gerek çiçekten ve gerekse balmumundan olsun" demektedir 1. Nahil, çok eski as~ rdan beri Orta Asya ve ~ran'dan gelen tezyini san'atlardand~r. ~eyh Sadi merhum (vefat~~ 690 H. 1292 M.) Gülistan'da: Nah~l-bendem veli ne der b'ustân S-dhidem men veli ne der Ken' an beytiyle nahilden bahsetmektedir. -

Contributions of Lala Har Dayal As an Intellectual and Revolutionary

CONTRIBUTIONS OF LALA HAR DAYAL AS AN INTELLECTUAL AND REVOLUTIONARY ABSTRACT THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF ^ntiat ai pijtl000pi{g IN }^ ^ HISTORY By MATT GAOR CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2007 ,,» '*^d<*'/. ' ABSTRACT India owes to Lala Har Dayal a great debt of gratitude. What he did intotality to his mother country is yet to be acknowledged properly. The paradox ridden Har Dayal - a moody idealist, intellectual, who felt an almost mystical empathy with the masses in India and America. He kept the National Independence flame burning not only in India but outside too. In 1905 he went to England for Academic pursuits. But after few years he had leave England for his revolutionary activities. He stayed in America and other European countries for 25 years and finally returned to England where he wrote three books. Har Dayal's stature was so great that its very difficult to put him under one mould. He was visionary who all through his life devoted to Boddhi sattava doctrine, rational interpretation of religions and sharing his erudite knowledge for the development of self culture. The proposed thesis seeks to examine the purpose of his returning to intellectual pursuits in England. Simultaneously the thesis also analyses the contemporary relevance of his works which had a common thread of humanism, rationalism and scientific temper. Relevance for his ideas is still alive as it was 50 years ago. He was true a patriotic who dreamed independence for his country. He was pioneer for developing science in laymen and scientific temper among youths. -

Women and Power: Female Patrons of Architecture in 16Th and 17Th Century Istanbul1

Women and Power: Female Patrons of Architecture in 16th and 17th Century Istanbul1 Firuzan Melike Sümertas ̧ Anadolu University, Eskisehir, ̧ TÜRKlYE ̇ The aim of this paper is to discuss and illustrate the visibility of Ottoman imperial women in relation to their spatial presence and contribution to the architecture and cityscape of sixteenth and seventeenth century Istanbul. The central premise of the study is that the Ottoman imperial women assumed and exercised power and influence by various means but became publicly visible and acknowledged more through architectural patronage. The focus is on Istanbul and a group of buildings and complexes built under the sponsorship of court women who resided in the Harem section of Topkapı Palace. The case studies built in Istanbul in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are examined in terms of their location in the city, the layout of the complexes, the placement and plan of the individual buildings, their orientation, mass characteristics and structural properties. It is discussed whether female patronage had any recognizable consequences on the Ottoman Classical Architecture, and whether female patrons had any impact on the building process, selection of the site and architecture. These complexes, in addition, are discussed as physical manifestation and representation of imperial female power. Accordingly it is argued that, they functioned not only as urban regeneration projects but also as a means to enhance and make imperial female identity visible in a monumental scale to large masses in different parts of the capital. Introduction Historical study, since the last quarter of the 20th The study first summarizes outlines the role of women century has concentrated on recognizing, defining, in the Ottoman society. -

Running Head: Correspondence of Ottoman Women

Correspondence of Ottoman Women 1 Running head: Correspondence of Ottoman Women The Correspondence of Ottoman Women during the Early Modern Period (16th-18th centuries): Overview on the Current State of Research, Problems, and Perspectives Marina Lushchenko Department of French, Hispanic and Italian Studies University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Correspondence of Ottoman Women 2 Abstract My main goal is to investigate problems and possible perspectives related to studies in Ottoman women’s epistolarity (16th-18th centuries). The paper starts with a review of the current state of research in this area. I then go on to discuss some of the major problems confronting researchers. Ottoman female epistolarity also offers many directions that future research may take. A socio-historical approach contributes to shed new light on the roles Ottoman women played within the family and society. A cultural approach or a gender-based approach can also provide interesting insight into Ottoman women’s epistolarity. Moreover, the fast computerization of scholarly activity suggests creating an electronic archive of Ottoman women’s letters in order to attract the attention of a wider scholarly audience to this field of research. Correspondence of Ottoman Women 3 INTRODUCTION In recent years researchers working in the field of gender studies have started to pay special attention to the place that letter-writing held in early modern women’s lives. As a source, letters provide, indeed, an incomparable insight into women’s thoughts, emotions and experiences, and help to make important advances towards a better understanding and evaluation of female education and literacy, social and gender interactions as well as roles played by women within the family circle, in society and, often, on the political stage. -

The Seljuks of Anatolia: an Epigraphic Study

American University in Cairo AUC Knowledge Fountain Theses and Dissertations 2-1-2017 The Seljuks of Anatolia: An epigraphic study Salma Moustafa Azzam Follow this and additional works at: https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds Recommended Citation APA Citation Azzam, S. (2017).The Seljuks of Anatolia: An epigraphic study [Master’s thesis, the American University in Cairo]. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/656 MLA Citation Azzam, Salma Moustafa. The Seljuks of Anatolia: An epigraphic study. 2017. American University in Cairo, Master's thesis. AUC Knowledge Fountain. https://fount.aucegypt.edu/etds/656 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by AUC Knowledge Fountain. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of AUC Knowledge Fountain. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Seljuks of Anatolia: An Epigraphic Study Abstract This is a study of the monumental epigraphy of the Anatolian Seljuk Sultanate, also known as the Sultanate of Rum, which emerged in Anatolia following the Great Seljuk victory in Manzikert against the Byzantine Empire in the year 1071.It was heavily weakened in the Battle of Köse Dağ in 1243 against the Mongols but lasted until the end of the thirteenth century. The history of this sultanate which survived many wars, the Crusades and the Mongol invasion is analyzed through their epigraphy with regard to the influence of political and cultural shifts. The identity of the sultanate and its sultans is examined with the use of their titles in their monumental inscriptions with an emphasis on the use of the language and vocabulary, and with the purpose of assessing their strength during different periods of their realm. -

(Self) Fashioning of an Ottoman Christian Prince

Amanda Danielle Giammanco (SELF) FASHIONING OF AN OTTOMAN CHRISTIAN PRINCE: JACHIA IBN MEHMED IN CONFESSIONAL DIPLOMACY OF THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MA Thesis in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Central European University Budapest CEU eTD Collection May 2015 (SELF) FASHIONING OF AN OTTOMAN CHRISTIAN PRINCE: JACHIA IBN MEHMED IN CONFESSIONAL DIPLOMACY OF THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY by Amanda Danielle Giammanco (United States of America) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU. ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner CEU eTD Collection ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest May 2015 (SELF) FASHIONING OF AN OTTOMAN CHRISTIAN PRINCE: JACHIA IBN MEHMED IN CONFESSIONAL DIPLOMACY OF THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY by Amanda Danielle Giammanco (United States of America) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Comparative History, with a specialization in Interdisciplinary Medieval Studies. Accepted in conformance with the standards -

Tiyatro : Hürrem Sultan – Aşk Hastası

G Ü N D E M Tiyatro Hürrem Sultan Son aylarda TRT’de ve başka bir özel kanalda harem hayatının iç Osmanlı tarihinde içinde kendi- yüzünü göstermeye çalışan iki dizi sine yurt içinde ve yurt dışındaki dolayısıyla yazılı ve görsel basında çalışmalarda özel bir yer ayrılan birçok haber, eleştiri ve yorum Kanuni Sultan Süleyman, 1512- yayınlarına tanık olduk. Ancak aynı 1566 yılları arasında hüküm sürerken tarihlerde Devlet Tiyatrosunda sah- hasekisi Hürrem (1500-1558) ile nelenen Hürrem Sultan hakkında gaze- nikah kıydırmış ve bu davranışıyla telerde ve dergilerde hemen hemen kendisinden bir hayli söz ettirmiştir. hiçbir yazar -sanat eleştirmeni de dâhil Hürrem Sultan nikâh kıyılmasından olmak üzere- kalem oynatmadı. Oysa sonra, sarayın hemen hemen bütün iç işlerinde önemli bir rol oynamıştır. bu Hürrem Sultan piyesi gerçekten Bütün kaynaklarda Slav kökenli görülmeye değer, güzel bir sanat eseri olduğu belirtilen Hürrem’in Lehistan idi. topraklarında esir edilen- Bir tıp doktoru olan ler arasında en talihli kişi Orhan Asena (7.1.1922- olduğu kesindir. Çünkü 15.2.2001) bu eseri çok Osmanlı Devleti'nde ilk önceleri, 1960 yılında kez bir cariye iken köle- yazmıştı. Aradan elli yıldan likten kurtulan, hür ve fazla geçmiş olmasına nikâh kıyılarak padişahın rağmen değerinden ve yegâne hanımlığına güncelliğinden bir şey mazhar olmuştur. Kendi öz kaybetmeyen bu piyes- oğullarının tahtın varisi ola- ten başka diğer eserleri de bilmesi için sarayda çeşitli sahnelenen Orhan Asena entrikalar çevirmiştir. Ayrı bu yolda çeşitli ödül- ve özel bir yönetime sahip lere da layık görülmüştü. olan harem hayatı, renkli olduğu ka- Kocaoğlan 1956’da Basın Yayın Ge- dar da bir hayli dramatik sahnelerle nel Müdürlüğünün açtığı yarışmada doludur. -

Cem Görür Doktora Tezi SON.Pdf

T.C. BİLECİK ŞEYH EDEBALİ ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI SULTAN III. MUSTAFA: AİLESİ, GÜNLÜK HAYATI, DİNİ VE İLMİ İLGİLERİ DOKTORA TEZİ Cem GÖRÜR Tez Danışmanı Prof. Dr. İlhami YURDAKUL Bilecik, 2020 10340908 T.C. BİLECİK ŞEYH EDEBALİ ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ TARİH ANABİLİM DALI SULTAN III. MUSTAFA: AİLESİ, GÜNLÜK HAYATI, DİNİ VE İLMİ İLGİLERİ DOKTORA TEZİ Cem GÖRÜR Tez Danışmanı Prof. Dr. İlhami YURDAKUL Bilecik, 2020 10340908 BEYAN “Sultan III. Mustafa: Ailesi, Günlük Hayatı, Dini ve İlmi İlgileri” adlı doktora tezimin hazırlık ve yazımı sırasında bilimsel ahlak kurallarına uyduğumu, başkalarının eserlerinden yararlandığım bölümlerde bilimsel kurallara uygun olarak atıfta bulunduğumu, kullandığım verilerde herhangi bir tahrifat yapmadığımı, tezin herhangi bir kısmını Bilecik Şeyh Edebali Üniversitesi veya başka bir üniversitedeki başka bir tez çalışması olarak sunmadığımı beyan ederim. Cem GÖRÜR ÖN SÖZ XVII. yüzyılın başında Osmanlı veraset sisteminin değişmesi, Osmanlı padişahlarının hayatlarında ciddi bir değişime sebep oldu. Şehzadelik dönemlerini sıkı bir gözetim altında geçirmeye başlayan padişahlar, bu zorlu sürecin ardından tahta oturduklarında, devletin geçirdiği sancılı süreçler karşısında tecrübesizliklerinin sıkıntısını fazlasıyla yaşadılar. XVIII. yüzyılın başında meydana gelen Edirne Vakası’yla birlikte, padişahlık dönemlerinde de bir mekân tahdidine uğramışlar ve ataları gibi İstanbul dışında uzun vakitler geçiremez olmuşlardı. Bu açıdan yaklaşıldığında XVIII. yüzyıl padişahlarının kendilerine has koşulları olduğu görülür. Buna mukabil tarih yazımında XVIII. yüzyılın, Tanzimat öncesi Türk “yenileşmesi/modernleşmesinin” öncülü bir süreci veya ihtişamlı “klasik” devir sonrası duraklama ve gerilemenin üzücü bir aşaması şeklinde ele alınması, dönemin padişahlarına da benzer bir perspektiften yaklaşılmasına sebep olmuştur. Dolayısıyla mevcut şartları içerisinde padişahların bizzat kendilerine, onların içinde bulundukları hayata/rutinlerine odaklanan çalışmalar son derece sınırlı kalmıştır. -

Experiencias De Intervención E Investigación: Buenas Prácticas, Alianzas Y Amenazas I Especialización En Patrimonio Cultural Sumergido Cohorte 2021

Experiencias de intervención e investigación: buenas prácticas, alianzas y amenazas I Especialización en Patrimonio Cultural Sumergido Cohorte 2021 Filipe Castro Bogotá, April 2021 2012-2014 Case Study 1 Gnalić Shipwreck (1569-1583) Jan Brueghel the Elder, 1595 The Gnalić ship was a large cargo ship built in Venice for the merchants Benedetto da Lezze, Piero Basadonna and Lazzaro Mocenigo. Suleiman I (1494-1566) Selim II (1524-1574 Murad III (1546-1595) Mehmed III (1566-1603) It was launched in 1569 and rated at 1,000 botti, a capacity equivalent to around 629 t, which corresponds to a length overall close to 40 m (Bondioli and Nicolardi 2012). Early in 1570, the Gnalić ship transported troops to Cyprus (which fell to the Ottomans in July). War of Cyprus (1570-1573): in spite of losing the Battle of Lepanto (Oct 7 1571), Sultan Selim II won Cyprus, a large ransom, and a part of Dalmatia. In 1571 the Gnalić ship fell into Ottoman hands. Sultan Selim II (1566-1574), son of Suleiman the Magnificent, expanded the Ottoman Empire and won the War of Cyprus (1570-1573). Giovanni Dionigi Galeni was born in Calabria, southern Italy, in 1519. In 1536 he was captured by one of Barbarossa Hayreddin Pasha’s captains and engaged in the galleys as a slave. In 1541 Giovanni Galeni converted to Islam and became a corsair. His skills and leadership capacity eventually made him Bey of Algiers and later Grand Admiral in the Ottoman fleet, with the name Uluç Ali Reis. He died in 1587. In late July 1571 Uluç Ali encountered a large armed merchantman near Corfu: it was the Moceniga, Leze, & Basadonna, captained by Giovanni Tomaso Costanzo (1554-1581), a 16 years old Venetian condottiere (captain of a mercenary army), descendent from a famous 14th century condottiere named Iacomo Spadainfaccia Costanzo, and from Francesco Donato, who was Doge of Venice from 1545 to 1553. -

![Fall of Constantinople] Pmunc 2018 Contents](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3444/fall-of-constantinople-pmunc-2018-contents-1093444.webp)

Fall of Constantinople] Pmunc 2018 Contents

[FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE] PMUNC 2018 CONTENTS Letter from the Chair and CD………....…………………………………………....[3] Committee Description…………………………………………………………….[4] The Siege of Constantinople: Introduction………………………………………………………….……. [5] Sailing to Byzantium: A Brief History……...………....……………………...[6] Current Status………………………………………………………………[9] Keywords………………………………………………………………….[12] Questions for Consideration……………………………………………….[14] Character List…………………...………………………………………….[15] Citations……..…………………...………………………………………...[23] 2 [FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE] PMUNC 2018 LETTER FROM THE CHAIR Dear delegates, Welcome to PMUNC! My name is Atakan Baltaci, and I’m super excited to conquer a city! I will be your chair for the Fall of Constantinople Committee at PMUNC 2018. We have gathered the mightiest commanders, the most cunning statesmen and the most renowned scholars the Ottoman Empire has ever seen to achieve the toughest of goals: conquering Constantinople. This Sultan is clever and more than eager, but he is also young and wants your advice. Let’s see what comes of this! Sincerely, Atakan Baltaci Dear delegates, Hello and welcome to PMUNC! I am Kris Hristov and I will be your crisis director for the siege of Constantinople. I am pleased to say this will not be your typical committee as we will focus more on enacting more small directives, building up to the siege of Constantinople, which will require military mobilization, finding the funds for an invasion and the political will on the part of all delegates.. Sincerely, Kris Hristov 3 [FALL OF CONSTANTINOPLE] PMUNC 2018 COMMITTEE DESCRIPTION The year is 1451, and a 19 year old has re-ascended to the throne of the Ottoman Empire. Mehmed II is now assembling his Imperial Court for the grandest city of all: Constantinople! The Fall of Constantinople (affectionately called the Conquest of Istanbul by the Turks) was the capture of the Byzantine Empire's capital by the Ottoman Empire.