Grain Color Stability and Classification of Hard White Wheat in the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2016 Supported by the Oklahoma Wheat Commission

artners in P rogress P W H E A T Wheat Research at OSU 2016 Supported by the Oklahoma Wheat Commission and the Oklahoma Wheat Research Foundation Oklahoma State University Division of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service P-1048 artners in rogress PP W H E A T Wheat Research at OSU 2016 Supported by the Oklahoma Wheat Commission and the Oklahoma Wheat Research Foundation Oklahoma State University Division of Agricultural Sciences and Natural Resources Oklahoma Agricultural Experiment Station Oklahoma Cooperative Extension Service P-1048 The pesticide information presented in this publication was current with federal and state regulations at the time of printing. The user is responsible for determining that the intended use is consistent with the label of the product being used. Use pesticides safely. Read and follow label directions. The information given herein is for educational purposes only. Reference to commercial products or trade names is made with the understanding that no discrimination is intended and no endorsement by the Cooperative Extension Service is implied. Oklahoma State University, in compliance with Title VI and VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Executive Order 11246 as amended, and Title IX of the Education Amendments of 1972 (Higher Education Act), the Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990, and other federal and state laws and regulations, does not discrimi- nate on the basis of race, color, national origin, genetic information, sex, age, sexual orientation, gender identity, religion, disability, or status as a veteran, in any of its policies, practices or procedures. -

Grain Grading Primer

Marketing and Regulatory Programs Grain Agricultural Marketing Service Grading Federal Grain Inspection Service Washington, D.C. Primer October 2016 United States Department of Agriculture Agricultural Marketing Service Federal Grain Inspection Service Informational Reference October 2016 Grain Grading Primer Foreword The effectiveness of the U.S. grain inspection system depends largely on an inspector’s ability to sample, inspect, grade, and certify the various grains for which standards have been established under the United States Grain Standards Act, as amended. This publication is designed primarily to provide information and instruction for producers, grain handlers, and students on how grain is graded. It is not designed for Official grain inspectors for they must necessarily use more detailed instruction than that provided herein. In view of this fact, the Federal Grain Inspection Service, published the Grain Inspection Handbook, Book II, Grain Grading Procedures, which documents the step-by-step procedures needed to effectively and efficiently inspect grain in accordance with the Official United States Standards for Grain. The mention of firm names or trade products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the United States Department of Agriculture over other firms or similar approved products not mentioned. Foreword Table of Contents The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in its programs on the basis of race, color, national origin, sex, religion, age, disability, political beliefs, and marital or familial status. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternate means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). -

Population Structure and Genome-Wide Association Studies In

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Population structure and genome‑wide association studies in bread wheat for phosphorus efciency traits using 35 K Wheat Breeder’s Afymetrix array Preman R. Soumya1,5, Amanda J. Burridge2, Nisha Singh3, Ritu Batra1, Renu Pandey 1*, Sanjay Kalia4, Vandana Rai3 & Keith J. Edwards2 Soil bioavailability of phosphorus (P) is a major concern for crop productivity worldwide. As phosphatic fertilizers are a non‑renewable resource associated with economic and environmental issues so, the sustainable option is to develop P use efcient crop varieties. We phenotyped 82 diverse wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) accessions in soil and hydroponics at low and sufcient P. To identify the genic regions for P efciency traits, the accessions were genotyped using the 35 K‑SNP array and genome‑ wide association study (GWAS) was performed. The high‑quality SNPs across the genomes were evenly distributed with polymorphic information content values varying between 0.090 and 0.375. Structure analysis revealed three subpopulations (C1, C2, C3) and the phenotypic responses of these subpopulations were assessed for P efciency traits. The C2 subpopulation showed the highest genetic variance and heritability values for numerous agronomically important traits as well as strong correlation under both P levels in soil and hydroponics. GWAS revealed 78 marker‑trait associations (MTAs) but only 35 MTAs passed Bonferroni Correction. A total of 297 candidate genes were identifed for these MTAs and their annotation suggested their involvement in several biological process. Out of 35, nine (9) MTAs were controlling polygenic trait (two controlling four traits, one controlling three traits and six controlling two traits). -

Lista De Alimentos Autorizados De

WIC de Autorizados Alimentos de Lista Octubre de 2018 de Octubre Fecha de Entrada en vigor vigor en Entrada de Fecha De conformidad con la Ley Federal de Derechos Civiles y los reglamentos y políticas de derechos civiles del Departamento de Agricultura de los EE. UU. (USDA, por sus siglas en inglés), se prohíbe que el USDA, sus agencias, oficinas, empleados e instituciones que participan o administran programas del USDA discriminen sobre la base de raza, color, nacionalidad, sexo, discapacidad, edad, o en represalia o venganza por actividades previas de derechos civiles en algún programa o actividad realizados o financiados por el USDA. Las personas con discapacidades que necesiten medios alternativos para la comunicación de la información del programa (por ejemplo, sistema Braille, letras grandes, cintas de audio, lenguaje de señas americano, etc.), deben ponerse en contacto con la agencia (estatal o local) en la que solicitaron los beneficios. Las personas sordas, con dificultades de audición o discapacidades del habla pueden comunicarse con el USDA por medio del Federal Relay Service [Servicio Federal de Retransmisión] al (800) 877-8339. Además, la información ¿PREGUNTAS? del programa se puede proporcionar en otros idiomas. Pregunte al personal de WIC o llame a la oficina Para presentar una denuncia de discriminación, complete el Formulario de Denuncia de Discriminación del Programa del USDA, (AD-3027) que está WIC de Maryland al 1-800-242-4942 o visite nuestro disponible en línea en: http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html y en cualquier oficina del USDA, o bien escriba una carta dirigida al USDA e sitio web en www.mdwic.org incluya en la carta toda la información solicitada en el formulario. -

Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes

National Plant Data Team August 2012 Edible Seeds and Grains of California Tribes and the Klamath Tribe of Oregon in the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology Collections, University of California, Berkeley August 2012 Cover photos: Left: Maidu woman harvesting tarweed seeds. Courtesy, The Field Museum, CSA1835 Right: Thick patch of elegant madia (Madia elegans) in a blue oak woodland in the Sierra foothills The U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) prohibits discrimination in all its pro- grams and activities on the basis of race, color, national origin, age, disability, and where applicable, sex, marital status, familial status, parental status, religion, sex- ual orientation, genetic information, political beliefs, reprisal, or because all or a part of an individual’s income is derived from any public assistance program. (Not all prohibited bases apply to all programs.) Persons with disabilities who require alternative means for communication of program information (Braille, large print, audiotape, etc.) should contact USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TDD). To file a complaint of discrimination, write to USDA, Director, Office of Civil Rights, 1400 Independence Avenue, SW., Washington, DC 20250–9410, or call (800) 795-3272 (voice) or (202) 720-6382 (TDD). USDA is an equal opportunity provider and employer. Acknowledgments This report was authored by M. Kat Anderson, ethnoecologist, U.S. Department of Agriculture, Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) and Jim Effenberger, Don Joley, and Deborah J. Lionakis Meyer, senior seed bota- nists, California Department of Food and Agriculture Plant Pest Diagnostics Center. Special thanks to the Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum staff, especially Joan Knudsen, Natasha Johnson, Ira Jacknis, and Thusa Chu for approving the project, helping to locate catalogue cards, and lending us seed samples from their collections. -

Test to Distinguish Between Red and White Grains of Wheat Treated with a Seed Dressing

TEST TO DISTINGUISH BETWEEN RED AND WHITE GRAINS OF WHEAT TREATED WITH A SEED DRESSING. Grain color is the only important character by which varieties of wheat can be grouped into types on visual examination of a seed sample. Two color types are recognized, the red wheats and the white wheats, although there is considerable variation in the intensity of the color between varieties of the red wheats, and the color of the grain in the white wheats is actually yellow. It is not normally difficult to clarify a particular variety of wheat as red or white-grained, but difficulties may be experienced in determining the color of individual grains when a sample has been treated with a fungicide as those usually incorporate an orange or pink dye. Difficulties may also be experienced if the sample has been subjected to weathering in the field during harvest, or premature ripening has resulted in a large proportion of grains with vitreous, as opposed to starchy, endosperm. In a review of methods for testing the genuineness of variety in the laboratory, Chmelar and Mostovoj (1938) referred to a method for identifying any grains of white wheat varieties in samples of varieties with red grains by soaking a representative portion in a 5% solution of potassium or sodium hydroxide for 15 minutes. The grains of white varieties then became cream-colored while the grains of red varieties became an intense red. This test has been used to confirm the separation of grains by color in routine purity tests on wheat. The method consists of immersing each four replicates of 25 grains in 25ml. -

Norandex Color Brochure

Norandex Color Brochure qualityedge.com colorsforhomes.com 888-784-0878 NORANDEXBROCH 06/10 Matching Accessories Fascia Drip Edge Trim Coil SOFFIT Drip Cap STARTER STRIP Rainware, Gutter Coil & Accessories Norandex Aluminum Trim Colors Fascia, Soffit, Drip Edge & Rainware White Beige Champagne Tan Sand Cactus Granite 280 827 819 327 809 200 204 Trim Coil Only Linen Cream Almond Dune Wheat Silver Sandstone Cobblestone 207 203 201 801 216 212 210 202 Sierra Tumbleweed Hazel Saddle Russet Ivy Wedgewood 211 214 205 209 208 206 215 Quality Edge - Additional Colors Fascia, Soffit, Drip Edge & Rainware Snowmist Eggshell Cozy Cottage Autumn Clay Prairie Heather Sandy Beige 523 503 606 Leaf 506 807 Sand 549 506 177 Norwood Terratone Sable Musket Brown Mocha Cypress Pewter 509 511 538 508 502 507 559 805 Eldridge Wineberry navy Forest Black Gray 605 604 521 522 518 BREATHE EASY Use the soffit with superior net free area. Available in: 12”, 16”, center vented, fully vented, solid, hidden vent and beaded. TruVent Hidden Vent Soffit TruBead Jet Vented Soffit TruLine: Extra Strength Soffit 3 inch 3 panel D5 (Solid & Vented), in solid and vented options D6 (Solid & Vented), 12” (No Vent, Center Vent & Full Vent), 16” (No Vent, Center Vent & Full Vent) 12" SOLID SOFIT 12" SOFFIT CENTER VENT 12" SOFFIT FULL VENT Published NFA Ratings: TruVent Hidden Vent Soffit 11 TruBead Soffit T3 Vented 10.1 TruLine Soffit 12” Center Vent 5.9 12” Full Vent 19.6 16” Center Vent 10.2 16” Full Vent 20.7 D5 Full Vent 22.5 D6 Full Vent 21.5 Pre-Engineered Pre-engineered .024 fascia products can save you even more time and provide nearly seamless installation. -

Liquicolor Permanente Shades 07-10-12.Pdf

LIQUICOLOR PERMANENTE INTENSE INTENSE INTENSE INTENSE GOLD RED NEUTRAL (RN) INTENSE RED (RR) RED VIOLET (RV) RED VIOLET (RRV) BASE INTENSE NEUTRAL (NN) NEUTRAL (N) ASH (A) ASH (A) ASH (AA) ASH (AA) NEUTRAL(GN) GOLD (G) REDPELIRROJO NEUTRAL (RN) RED (R) INTENSEPELIRROJO RED (RR) REDPELIRROJO VIOLET (RV) REDPELIRROJO VIOLET (RRV) NEUTRAL INTENSO NEUTRAL CENIZO CENIZO CENIZO INTENSO CENIZO INTENSO DORADO NEUTRAL GOLDDORADO (G) PELIRROJONEUTRAL PELIRROJORED (R) PELIRROJOINTENSO PELIRROJOVIOLETA VIOLETAPELIRROJO INTENSO LEVEL/NIVEL DORADO NEUTRAL PELIRROJO INTENSO VIOLETA VIOLETA INTENSO 12 HIGH-LIFT BLONDE 12N/HL-N 12A/HL-V 12AA-B/HL-B 12AA-BV 12G / HL-G HIGH LIFT HIGH LIFT HIGH LIFT ULTRA HIGH LIFT ULTRA HIGH LIFT GOLDEN BLONDE NEUTRAL BLONDE COOL BLONDE COOL BLONDE BLUE COOL BLONDE BLUE VIOLET 10 LIGHTEST BLONDE RUBIO CLARÍSIMO 10N/12B1 10GN/12G2 OUR FIRST NN 10G / 12G LIGHTEST NEUTRAL BLONDE LIGHTEST GOLD LIQUID COLOR LIGHTEST GOLDEN BLONDE blondest beige NEUTRAL BLONDE blondest blonde blondest gold 9 VERY LIGHT BLONDE RUBIO MUY CLARO 9NN 9N/89N 9A/26D 9A-N/40D 9AA/20D 9AA-BV/30D VERY LIGHT RICH VERY LIGHT VERY LIGHT VERY LIGHT COOL VERY LIGHT ULTRA VERY LIGHT ULTRA COOL NEUTRAL BLONDE NEUTRAL BLONDE COOL BLONDE NEUTRAL BLONDE COOL BLONDE BLONDE BLUE VIOLET lightest neutral blonde winter wheat topaz arctic blonde flaxen blonde 8 LIGHT BLONDE RUBIO CLARO 8NN 8N/88N 8A / 28D 8GN/27G 8RN / 71RG 8R / 29R LIGHT RICH LIGHT LIGHT COOL BLONDE LIGHT GOLD NEUTRAL LIGHT RED NEUTRAL LIGHT RED BLONDE NEUTRAL BLONDE NEUTRAL BLONDE autumn mist BLONDE -

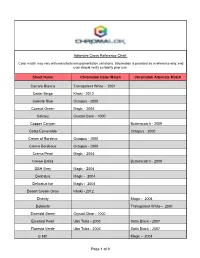

Chromalok Color Chart

Adhesive Cross Reference Chart Color match may vary with manufacturers pigmentation variations. Information is provided as a reference only; end user should verify suitability prior use. Sheet Name Chromalok Color Match Chromalok Alternate Match Carrara Bianco Transparent White - 2001 Cedar Beige Khaki - 2012 Celeste Blue Octopus - 2000 Coastal Green Magic - 2004 Coliseu Crystal Clear - 1000 Copper Canyon Butterscotch - 2009 Costa Esmeraldo Octopus - 2000 Cream of Bordeux Octopus - 2000 Crema Bordeaux Octupus - 2000 Crema Pearl Magic - 2004 Creme Bahia Butterscotch - 2009 DBH Grey Magic - 2004 Delicatus Magic - 2004 Delicatus Ice Magic - 2004 Desert Cream Onyx Khaki - 2012 Divinity Magic - 2004 Dolomite Transparent White - 2001 Emerald Green Crystal Clear - 1000 Emerald Pearl Uba Tuba - 2003 Satin Black - 2007 Floresta Verde Uba Tuba - 2003 Satin Black - 2007 G 681 Magic - 2004 Page 1 of 9 Adhesive Cross Reference Chart Color match may vary with manufacturers pigmentation variations. Information is provided as a reference only; end user should verify suitability prior use. G03 Satin Black - 2007 G04 Uba Tuba - 2003 Satin Black - 2007 G06 Magic - 2004 G07 Khaki - 2012 G08 Khaki - 2012 G09 Satin Black - 2007 G11 Uba Tuba - 2003 Satin Black - 2007 Galaxy Black Satin Black - 2007 Ghiblee Khaki - 2012 Giallo Fiesta Magic - 2004 Giallo Fiorito Khaki - 2012 Giallo Latina Butterscotch - 2009 Giallo Valcelio Khaki - 2012 Giallo Veneziano Butterscotch - 2009 Khaki - 2012 Giallo Verona Magic - 2004 Golden Brazil Butterscotch - 2009 Golden Caramel Butterscotch - 2009 Golden Garnet Khaki - 2012 Magic - 2004 Golden King Khaki - 2012 Golden Oak Khaki - 2012 Golden Wave Butterscotch - 2009 Gran Perla Magic - 2004 Page 2 of 9 Adhesive Cross Reference Chart Color match may vary with manufacturers pigmentation variations. -

S84 Diagnosing Wheat Production Problems in Kansas

Diagnosing WHEAT PRODUCTION PROBLEMS in Kansas Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service Wheat, like all crops, may suffer from a number of insect, disease, weed, nutritional, and environmental stresses. This publication will help in diagnosing likely causes of slow growth, distorted appearance, off-colors, injury, and death of wheat plants from planting through harvest. 1 Contents Fall Emergence 3 and Growth Spring Green Up 11 to Heading Heading 36 to Maturity 2 Fall Emergence and Growth 1 Poor stand establishment is the first problem produc- ers might encounter after planting. Poor stands can be caused by a number of problems, such as a plugged drill, poor seed quality, dry soil, deep planting, soil crusting, diseases, and insects. Take time to examine the evi- dence. Look for field patterns. Closer examina- tion of the situation will help determine the causes of poor stands. 2 Seed germination was initiated, as seen by the small radical or seed root that erupted from the seed, but it has now stopped. Apparently, moisture was sufficient to initiate germination, but was inadequate to sustain it. Dry soil has caused the germination/emergence process to stop. This is common with shallow plantings followed by several days of hot, drying winds. Seed in this condition can remain viable for a limited time, but if the seed becomes soft and spongy, the chances of it regrowing are not good. 3 3 Preplant herbicide injury can cause emergence problems in certain cases. Some herbicides, such as Treflan and Fargo, cause these prob- lems if used improperly and when cold, wet conditions follow planting. -

COLOR GELS COLOR EQ SHADES 1 Oz

REDKEN.COM BE PART OF IT. IT. OF PART BE INSPIRED. GET Redken Distributor Locator: Distributor Redken 1-800-542-7256 Redken Certified Haircolorist Program: Haircolorist Certified Redken Redken.com or redkencolorcert.com or Redken.com Redken Exchange: Redken 1-800-545-8157 Technical Assistance: Technical 1-800-423-5280 SHADE CHART SHADE For more information: more For Redken.com ASH BLUES ASH NEW PERMANENT CONDITIONING HAIRCOLOR CONDITIONING PERMANENT SHADES EQ SHADES Processing Solution Processing ml) (60 oz. 2 COLOR GELS COLOR EQ SHADES 1 oz. (30 ml) 08T Silver Silver 08T ml) (30 oz. 1 SHADES EQ SHADES Mojave 08N ml) (30 oz. 1 Formula 1 Formula GLAZE BLONDE ICING BLONDE Conditioning Cream Developer Cream Conditioning volume 30 parts 2 BLONDE ICING BLONDE Power Lift Conditioning Cream Lightener Cream Conditioning Lift Power part 1 Formula 2 Formula BLONDE ICING BLONDE Conditioning Cream Developer Cream Conditioning volume 20 parts 2 BLONDE ICING BLONDE Power Lift Conditioning Cream Lightener Cream Conditioning Lift Power part 1 Formula 1 Formula HIGHLIGHT COLOR GELS COLOR Developer volume 30 ml) (60 oz. 2 COLOR GELS COLOR 1 oz. (30 ml) 7AB Moonstone Moonstone 7AB ml) (30 oz. 1 COLOR GELS COLOR Twilight 5AB ml) (30 oz. 1 Formula 2 Formula COLOR GELS COLOR Developer volume 20 ml) (60 oz. 2 COLOR GELS COLOR 1 oz. (30 ml) 7AB Moonstone Moonstone 7AB ml) (30 oz. 1 COLOR GELS COLOR Twilight 5AB ml) (30 oz. 1 Formula 1 Formula BASE Natural Level 4 Level Natural COVER MODEL’S FORMULA MODEL’S COVER All rights reserved. 50003898 7/09 50003898 reserved. -

Testing Human Consumption Common Wheat's Classes

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Papers in Economics Testing Separability for Common Wheat Qualities in French Import Demand Market Using Aids and Rotterdam Demand Models Rabelais Yankam Njonou e-mail: [email protected] Bruno Henry De Frahan Yves Surry Paper prepared for presentation at the Xth EAAE Congress ‘Exploring Diversity in the European Agri-Food System’, Zaragoza (Spain), 28-31 August 2002 Copyright 2002 by Rabelais Yankam Njonou, Bruno Henry De Frahan and Yves Surry. All rights reserved. Readers may make verbatim copies of this document for non- commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright notice appears on all such copies. Xth EAAE congress, Zaragoza, 28-31 July 2002 Yankam, Henry de Frahan and Surry UNIVERSITE CATHOLIQUE DE LOUVAIN RURAL ECONOMICS UNIT TESTING SEPARABILITY FOR COMMON WHEAT QUALITIES IN FRENCH IMPORT DEMAND MARKET USING AIDS AND ROTTERDAM DEMAND MODELS Rabelais Yankam Njonou(a), Bruno Henry De Frahan(b) and Yves Surry (c) A contributed paper to the Xth EAAE Congress Zaragoza, Spain August, 28-31 2002 (a) Doctoral student, Rural Economics Unit, Université Catholique de Louvain, Belgium ([email protected]) (b) Professor, Rural Economics Unit, Université Catholique de Louvain, Belgium (c) Senior researcher, INRA, Rennes, France Copyright 2002 by Rabelais Yankam Njonou, Bruno Henry De Frahan and Yves Surry. All rights reserved. Readers may make copies of this document for non-commercial purposes by any means, provided that this copyright appears on all such copies. May, 2002 1 Xth EAAE congress, Zaragoza, 28-31 July 2002 Yankam, Henry de Frahan and Surry Key words: Separability, Import demand, Rotterdam and AIDS demand models, wheat qualities Abstract: This study has used a corrected likelihood ratio, with AIDS and Rotterdam demand models, to test separability in three separable (A, B, C) wheat import demand structures on the French common wheat market.