Book 2 -Journeyman

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London

THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors’ Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London THE DECEMBER SALE Collectors' Motor Cars, Motorcycles and Automobilia Thursday 10 December 2015 RAF Museum, London VIEWING Please note that bids should be ENQUIRIES CUSTOMER SERVICES submitted no later than 16.00 Wednesday 9 December Motor Cars Monday to Friday 08:30 - 18:00 on Wednesday 9 December. 10.00 - 17.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5801 +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 Thereafter bids should be sent Thursday 10 December +44 (0) 20 7468 5802 fax directly to the Bonhams office at from 9.00 [email protected] Please see page 2 for bidder the sale venue. information including after-sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax or SALE TIMES Motorcycles collection and shipment [email protected] Automobilia 11.00 +44 (0) 20 8963 2817 Motorcycles 13.00 [email protected] Please see back of catalogue We regret that we are unable to Motor Cars 14.00 for important notice to bidders accept telephone bids for lots with Automobilia a low estimate below £500. +44 (0) 8700 273 618 SALE NUMBER Absentee bids will be accepted. ILLUSTRATIONS +44 (0) 8700 273 625 fax 22705 New bidders must also provide Front cover: [email protected] proof of identity when submitting Lot 351 CATALOGUE bids. Failure to do so may result Back cover: in your bids not being processed. ENQUIRIES ON VIEW Lots 303, 304, 305, 306 £30.00 + p&p AND SALE DAYS (admits two) +44 (0) 8700 270 090 Live online bidding is IMPORTANT INFORMATION available for this sale +44 (0) 8700 270 089 fax BIDS The United States Government Please email [email protected] has banned the import of ivory +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 with “Live bidding” in the subject into the USA. -

Bentley Speed Six the Ultimate in Power, Luxury and Competition Pedigree

FORD MODEL T MAZDA COSMO FORD XR6 TF R47.00 incl VAT May 2017 BENTLEY SPEED SIX THE ULTIMATE IN POWER, LUXURY AND COMPETITION PEDIGREE STYLE & SUBSTANCE COMMEMORATING ENZO RENAULT’S CARAVELLE AND R8/10 FERRARI ENZO – FRENCH FLAIR THE MAN AND THE CAR DICKON DAGGITT | BMW 2002 RESTORED | DENNIS GUSCOTT PCC_Porsche Classic_210x276.qxp_Porsche 210x275 2017/04/05 11:46 AM Page 1 www.porschecapetown.com The first Porsche built boasted exceptional everyday practicality. Nothing has changed. Porsche Centre Cape Town. As a Porsche Classic Partner, our goal is the maintenance and care of historic Porsche vehicles. With expertise on site, Porsche Centre Cape Town is dedicated to ensuring your vehicle continues to be what it has always been: 100% Porsche. Our services include: • Classic Sales • Classic Body Repair • Genuine Classic Parts • Classic Service Porsche Centre Cape Town Corner Century Avenue and Summer Greens Drive, Century City Tel: 021 555 6800 CONTENTS — CARS BIKES PEOPLE AFRICA — MAY 2017 WORK & PLAY THE ROTARY CLUB 03 Editor’s point of view 64 Mazda Cosmo turns 50 CLASSIC CALENDAR DYNAMIC BEST-SELLER 06 Upcoming events for 2017 70 A modern classic – Mazda MX-5 NEWS & EVENTS PADKOS 08 All the latest from the classic scene 72 Backseat Driver – a female perspective THE MAGIC FORMULA 18 50 years of Formula Ford racing A CLASSIC RACER 74 Bike racer and tuner Dennis Guscott CARBS & COFFEE 22 All the ingredients THE FAMOUS FELINE’S FOUNDER 78 Sir William Lyons COMMEMORATING ENZO 24 Celebrating Ferrari’s 70th THE PERFECT CLASSIC with an Enzo -

Alan and Richard Jensen Produced Their First Car in 1928 When They

Alan and Richard Jensen produced their first car in 1928 when they converted a five year old Austin 7 Chummy Saloon into a very stylish two seater with cycle guards, louvred bonnet and boat-tail. This was soon sold and replaced with another Austin 7. Then came a car produced on a Standard chassis followed by a series of specials based on the Wolseley Hornet, a popular sporting small car of the time. The early 1930s saw the brothers becoming joint managing directors of commercial coachbuilders W J Smith & Sons and within three years the name of the company was changed to Jensen Motors Limited. Soon bodywork conversions followed on readily available chassis from Morris, Singer, Standard and Wolseley. Jensen’s work did not go unnoticed as they received a commission from actor Clark Gable to produced a car on a US Ford V8 chassis. This stylish car led to an arrangement with Edsel Ford for the production of a range of sports cars using a Jensen designed chassis and powered by Ford V8 engines equipped with three speed Ford transmissions. Next came a series of sporting cars powered by the twin-ignition straight eight Nash engine or the Lincoln V12 unit. On the commercial side of the business Jensen’s were the leaders in the field of the design and construction of high-strength light alloys in commercial vehicles and produced a range of alloy bodied trucks and busses powered by either four-cylinder Ford engines, Ford V8s, or Perkins diesels. World War Two saw sports car production put aside and attentions were turned to more appropriate activities such as producing revolving tank gun turrets, explosives and converting the Sherman Tank for amphibious use in the D-Day invasion of Europe. -

Standard Steel - Jubileumsraketten - Sommers Rolls-Royce INNEHÅLL Scandinavian Sections No.1.2020

ROLLS-ROYCE ENTHUSIASTS’ CLUB BULLETIN SCANDINAVIAN SECTIONS. NO.1.2020 Standard Steel - Jubileumsraketten - Sommers Rolls-Royce INNEHÅLL Scandinavian sections No.1.2020 VI ÄR NU GENERALAGENTER I SKANDINAVIEN FÖR INTROCARS RESERVDELSSERIE PRESTIGE PARTS® Prestige Parts®-serien skapades för att möta behovet av reservdelar till klassiska Rolls-Royce & Bentley där originaldelar inte längre finns att köpa eller är onödigt dyra. Man strävar alltså efter att få ner priset till kund jämfört med originaldelar. Varumärket har åtagit sig att introducera produkter som uppfyller eller överskrider tillverkarens specifikationer för originalutrustning (OE) och erbjuder som sådan en 3-års garanti över hela världen på hela sortimentet som nu innehåller över 5 000 artiklar. När du köper delarna via oss betalar du samma pris som om du skulle beställa dem direkt på IntroCars hemsida och vi erbjuder dessutom kostnadsfritt personlig rådgivning som borgar för att du verkligen får rätt delar till din bil. Här är några exempel. CD270 Oljefilter. Bentley MK VI & UG3848 Huvudbromscylinder 3/4”. UD12956 Värmekran. Bentley & Rolls- Rolls-Royce Silver Dawn & Wraith. Bentley S & Rolls-Royce Silver Cloud. Royce. 1966-77.Vårt pris 2.125:- 1946-51. Vårt pris 506:- 1955-66. Vårt pris 6.112:- Original 4.000:- men har utgått. Original har utgått. Original 17.000:- men har utgått. 2 Meddelanden från sektionerna 24 Spelbo gård 4 Den stora Englandsresan 2018 26 Säg adjö till Mulsanne 6 Vad menas med Standard Steel? 28 En svensk GT3-R 13 Nya rekord 30 Volvohandlarens Rolls-Royce 14 Jubileumsraketten 38 60 år med V8 18 Franay eller Chapron? 39 Svenska sektionens styrelse 21 Bentley Motors på bättringsvägen 40 Nytt fra bestyrelsen i Hunt House 22 The Rose Phantom CD6000GMF Broms-accumulator. -

Your Reference

MINI United Kingdom Corporate Communications Media Information 8 March 2013 A CENTURY OF CAR-MAKING IN OXFORD Plant’s first car was a Bullnose Morris Oxford, produced on 28 March 1913 Total car production to date stands at 11,655,000 and counting Over 2,250,000 new MINIs built so far, plus 600,000 classic Minis manufactured at Plant Oxford Scores of models under 14 car brands have been produced at the plant Grew to 28,000 employees in the 1960s As well as cars, produced iron lungs, Tiger Moth aircraft, parachutes, gliders and jerry cans, besides completing 80,000 repairs on Spitfires and Hurricanes Principle part of BMW Group £750m investment for the next generation MINI will be spent on new facilities at Oxford The MINI Plant will lead the celebrations of a centenary of car-making in Oxford, on 28 March 2013 – 100 years to the day when the first “Bullnose” Morris Oxford was built by William Morris, a few hundred metres from where the modern plant stands today. Twenty cars were built each week at the start, but the business grew rapidly and over the century 11.65 million cars were produced. Today, Plant Oxford employs 3,700 associates who manufacture up to 900 MINIs every day, and has contributed over 2.25 million MINIs to the total tally. Major investment is currently under way at the plant to create new facilities for the next generation MINI. BMW Group Company Postal Address BMW (UK) Ltd. Ellesfield Avenue Bracknell Berks RG12 8TA Telephone 01344 480320 Fax 01344 480306 Internet www.bmw.co.uk 0 MINI United Kingdom Corporate Communications Media Information Date Subject A CENTURY OF CAR-MAKING IN OXFORD Page 2 Over the decades that followed the emergence of the Bullnose Morris Oxford in 1913, came cars from a wide range of famous British brands – and one Japanese - including MG, Wolseley, Riley, Austin, Austin Healey, Mini, Vanden Plas, Princess, Triumph, Rover, Sterling and Honda, besides founding marque Morris - and MINI. -

Gateway Relay

Gateway Relay Vol VI, No. 3 St Louis Sports Car Council December 2016 Council News & Notes Up & Coming 12 Jan 17—Annual Gateway VCOA Holiday Party, at the Lazy River Grill, 631 In and around our hope that all Big Bend Rd, Ballwin (northeast corner, Big Bend Sulphur Spring Rd). Starts at are enjoying the holiday season, 6:30 PM, with dinner at 7 PM. If you plan to attend, please RSVP to gate- a reminder to member club offic- [email protected]; the first 20 families to respond will receive a special ers: the annual web hosting pay- gift. ment is due. Still only $20, paya- ble to the editor, contact infor- 14 Jan 17—St Louis Chapter BMWCCA Holiday Party, at Fast Lane Classic mation at the bottom of the last cars, 427 Little Hills Industrial Blvd, St Charles, 6 PM to 10 PM. page. Obviously, we hope all member clubs are satisfied mem- 14 Jan 17—Jaguar Association of Greater St Louis Annual Awards Din- ber clubs and will re-up for anoth- ner, at Deer Creek Club, 9861 Deer Creek Hill. Starts at 6:30 PM, monitor er year. www.jagstl.com and the online Growl. We had the shortest day of the 16 Jan 17—MG Club of St Louis Tech Session No. 1, at Hi-Tech Collision Repair, year about 10 days ago, followed 2618 Woodson Rd, Overland; presentation on installing headlight relays. 7 PM to 9 by two nights of ice which made PM. driving around greater St Louis 21 Jan 17—Gateway VCOA Bald Eagle Days, at Pere Marquette State Park. -

1 Oxford Stadium

Oxford Stadium – Factual Report and Assessment of Significance for Oxford Heritage Assets Register Review Panel Introduction and Background Oxford Stadium has been nominated by the public as a potential addition to the Oxford Heritage Assets Register. The register is a locally maintained list of non-designated heritage assets that the Council have recognised as having a degree of significance meriting consideration in planning decisions because of their heritage interest as described in the National Planning Policy Framework. Inclusion of non-designated heritage assets on the register is dependent on their fulfilling criteria adopted by the City Council and will be subject to review by a panel of City Councillors prior to adoption. An adopted nomination form sets out grounds on which a nominated heritage asset may be deemed to fulfil these conditions. For further details of the Oxford Heritage Assets Register, the criteria and nomination, review and adoption process please see the project website at: http://www.oxford.gov.uk/PageRender/decP/HeritageAssetRegister.htm This report has been prepared to inform the review of the nomination of the Greyhound Stadium for registration as a heritage asset. It includes details of Greyhound Stadia as a class of historic place, information about the development history of the site and surrounding area and a review of the history and architecture of the greyhound stadium. The concluding section provides a review of the greyhound stadium using the nomination form and criteria for the heritage assets register to consider where it might have heritage interest, heritage value and significance. Consultees are invited to provide information to enhance the accuracy of the information provided and may comment on the assessment of the Greyhound Stadium’s significance to inform the Council’s review of its nomination. -

B R a N D D E

BRAND DECK PREPARED BY LICENSING MANAGEMENT INTERNATIONAL HISTORY British Motor Heritage represents the classic marques of Austin, Morris, Wolseley and Rover together with the iconic British sports cars of MG and Austin-Healey. All are available for worldwide license. The BMH licensed products and designs have been inspired by the original sales brochures and advertising material held in the BMH archive. 1 THE BMH LOGO BRAND ATTRIBUTES ! Elegant ! Refined ! Sophisticated ! Masculine ! A rich British legacy and roots ! Traditional ! Adventurous ! Classic BMC, Nuffield and the Heritage logo are ! Nostalgic/Vintage trademarks of British Motor Heritage. ! Attention to detail ! Style British Motor Heritage and its logos are the registered The British Motor Heritage Brand encompasses a trademarks of British Motor Heritage Limited. The trademarks collection of classic car marques representing the golden were commissioned by the company in 1983 and have been in era of British car manufacturing. continual use ever since. The British Motor Heritage collection of licensed products Over the years, the Heritage trademarks have become the sign utilising the approved marques is targeted at men over 21 for quality of service and manufacture. The use of the logos has who may have fond sentimental memories of owning their been identified with Specialist Approval which is the Quality own MGs, Morris Minors or Austin-Healeys in their youth. Benchmark for the Classic Car Industry and with Quality Original Equipment product. We believe that collectors of fine wine, memorabilia and classic cars would be a key target for this Brand. The BMH Brand offers a prime opportunity for gift giving. 2 BMH MARQUES THE BMH MARQUES ARE AS FOLLOWS 3 BMH MARQUES - AUSTIN Registered in 1909, the Austin Word form was used on cars and literature well into the late 1930s. -

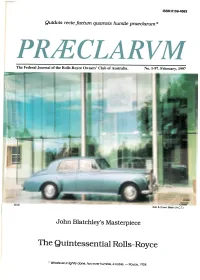

The Quintessential Rolls-Royce

ISSN 0159-4583 Quidvis recte facturn. quamvis hurnile praeclarurn* PR/ECLARVM The Federal Journal of the Rolls-Royce Owners’ Club of Australia. No. 1-97. February, 1997 It IW Si I }L SED51 Bob & Down Skilled (A.C.T.) John Blatchley’s Masterpiece The Quintessential Rolls-Royce * Whatever is rightly done, however humble. Is noble. — Royce, 1924. Sag s ' j e. 1 H w si if*■Si Aj ■/ 1 1 ■■■'If j I a i S i Mils A i f ■ * Bl-B I I £i i i If Ml N A X It ■■r mHMHl ■ You may think these two professionals are similar... but the guy on the left doesn't offer a 3-year warranty on parts. Skilled hands, a sharp mind, and years of training. A lot goes into being a qualified Rolls-Royce and Bentley technician, but then few jobs are more important than maintaining the health of the world's finest motor cars. There's only one place in Sydney where you'll find the capabilities of qualified Rolls-Royce and Bentley technicians, York Motors. So sure are we of our staff's expertise, that we gladly offer a three-year warranty on parts and labour, and a remarkable five-year warranty on exhaust system parts and labour for Rolls-Royce and Bentley Motor Cars dating from 1956. Whether your Rolls-Royce or Bentley needs complex repairs, or just a simple government check, R T A nobody else in Sydney offers the service, the confidence, Authorised Inspection Station Safety Inspection Report or the warranty coverage of York Motors. -

The MG Car Club Geelong Inc

The MG Car Club Geelong Inc. Selected Indexes of articles in indexed magazines. Many of these magazines are missing from our Library, please return if you have them. The Index is not complete but is a 'work in progress' and will be updated regularly. Only articles of on-going historical or technical interest are indexed. I have included any articles about the history of the MG Company, MG cars, or the people who were involved in either. I have not listed articles about Club Runs, Competition Events, or non-technical reports of Club Members' MGs as many of these are only relevant to Members in the UK. Use <Ctrl><f> to open the pdf search box to find keywords from articles, or to jump to the latest indexed edition of the magazines. To go to latest:- BMC Experience, insert text "latestbmc" in the search box MGCC G-Torque, insert text "latestgtorque" in the search box Octane, insert text "latestoctane" in the search box MG Octagon CC Bulletin, insert text 'latestoctagonbulletin' in the search box Librarian - The MGCC Geelong Inc. Index of Technical Articles from G-Torque - MGCC Geelong Magazine Edition Article Title EDITION ARTICLE PAGES 1990 Believe it or Not - This article is a personal account of installing an Austin 1800 engine in an MGB. It has good February 1990 basic information and tips on how to install the engine and some pitfalls.Barry Arthur Bits and Pieces - A brief description outlining the factors of MG handling and what may fix it. For example front March 1990 sway bar, ride height tyre pressure. -

Innovation Studies and the History of Technology

Trying to secure the past: innovation studies and the history of technology A thesis submitted to the University of Manchester for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in the Faculty of Humanities Jonathan Aylen 2018 1 Contents page Listing of Publications 3 Abstract 4 Declaration 5 Copyright Statement 5 Jonathan Aylen, Statement of Eligibility 6 Introduction 1. Selection of a coherent set of papers 8 2. Historical methods in the study of technology 23 3. The nature of the innovation process 30 4. Lessons from innovation research 41 5. Bibliography 46 6. Corrections and updates 57 7. Impact of this research 59 Papers Blue Danube - Britain’s post-war atomic bomb 61 Stretch - how innovation continues once investment is made 62 Bloodhound - building the Ferranti Argus process control computer 63 Open versus closed innovation - development of the wide strip mill for steel 64 Construction of the Shotton wide strip mill 65 Development of computer applications in the iron and steel industry 66 2 “Trying to secure the past: innovation studies and the history of technology” "People work much in order to secure the future; I gave my mind much work and trouble, trying to secure the past" Isak Dinesen/also known as Karen von Blixen-Finecke (1885-1962), Shadows on the Grass, Harmondsworth: Penguin, 1990, essay “Echoes from the Hills”, p.116 papers: 1. Jonathan Aylen, “First waltz: development and deployment of Blue Danube, Britain’s post-war atomic bomb”, The International Journal for the History of Engineering & Technology, vol. 85, no.1, January 2015, pp.31-59 2. -

Austin Motor Company

Austin Motor Company Few names in British motoring history are better known than that of Austin. For many years the company claimed that ‘You buy a car but you invest in an Austin’. A young Herbert Austin (1866–1941) travelled to Australia in 1884 seeking his fortune. In mid 1886 he began working for Frederick Wolseley’s Sheep Shearing Machine Company in Sydney. Austin returned to England with Wolseley in 1889 to establish a new factory in Birmingham, where he became Works Manager. Austin built himself a car in 1895/6 followed a few months later by a second for Wolseley, a production model followed in 1899. A new company, backed by Vickers, bought the car making interests of the Wolseley Company in 1901 with Austin taking a leading role. Following a disagreement over engine design in 1905 Austin left, setting up his own Austin Motor Company in a disused printing works at Longbridge in December of that year. The first Austin was a 4 cylinder 5182cc 25/30hp model which became available in the spring of 1906. This was replaced by the 4396cc 18/24 in 1907. 5838cc 40hp and 6 cylinder 8757cc 60hp models were also produced. The 6 cylinder engine also formed the basis for a 9657cc 100hp engine used in cars for the 1908 Grand Prix. A 7hp single cylinder car was marketed in 1910/11. The company expanded rapidly, output growing from 200 cars in 1910 to 1100 in 1912. By 1914 there was a three model line-up of Ten, Twenty and Thirty. The Austin Company underwent a massive expansion during World War I with the workforce growing from 2,600 to more than 22,000.