Television Reviews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page -

Dr. Alma Martinez Diversity in America: the Representation of People of Color in the Media

Dr. Alma Martinez Diversity in America: The Representation of People of Color in the Media STATEMENT I am Dr. Alma Martinez. I am an American film, television and stage actor and, as well, a university professor and published author. I hold a PhD in Drama from Stanford University, a MFA in Acting from the University of Southern California, and am a Dartmouth College Cesar Chavez Dissertation Fellow alum, a Fulbright Scholar, and a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, Actors Branch (AMPAS). My induction into AMPAS reflects my extensive body of work in the films Zoot Suit, Under Fire, Barbarosa, Born in East LA, Cake, Transpecos, Crossing Over, Ms. Purple, Clemency and in TV programs such as Gentefied, Undone, Queen Sugar, The Bridge, American Crime Story: People vs OJ, Elena of Avalor, The Terror Infamy, Corridos Tales of Passion and Revolution among others. I have acted on Broadway, Off-Broadway, in regional theatres across the country and on Mexican and European stages. These combined projects have garnered: Sundance Film Festival Grand Jury Awards, Oscar, Golden Globe and Emmy awards/nominations, Tony Award, and Los Angeles Drama Critics and New York Drama Desk awards. In my decades of working in the entertainment industry, I have shared the screen and stage with distinguished acting colleagues Gene Hackman, Edward James Olmos, Alfre Woodard, Lupe Ontiveros, Ed Harris, Jean Louis Trintignant, George Takei, Liev Schreiber, Diane Weist, Danny Trejo, Nick Nolte, Jennifer Aniston, Cheech Marin, Frances Conroy and worked with directors like Zack Snyder, America Ferrera, Ryan Murphy, Ava DuVernay, Luis Valdez, Chinonye Chukwa, Roger Spottiswoode, Peter Medak, Jill Soloway, Fred Schepsi, and Daniel Barnez among others. -

Hard Copy Jeremy Conner Resume

Jeremy Conner www.JermyConner.com 407-595-5373 [email protected] (SAG/Aftra) Height: 5’10.5” Weight: 155 lbs Neck: 15.5 Sleeve: 32 Waist: 31 Inseam: 32 Jacket: 40R Shoe: 10.5 Eye Color: Blue/Gree Hair Color: Light Brown Film Sextuplets Finding Steve McQueen Tusk Little Monumental Captive Stuber Caroursel The Taking Boss Level Hot Summer Nights Lincoln Goosebumps:Slappy Halloween Allegiant Hick Summer Night Sleepless Who’s Your Monkey? War With Grandpa Free State of Jones Bleed In Dubious Battle Strangers 2 Nice Guys Pitch Perfect 3 Insurgent Television Insatiable Season 2 – 6 Episodes The Walking Dead Seasons 1-8 – 8 Episodes Graceland – “Gratis” The Righteous Gemstones – Episode 104 Stranger Things - “Episode 209” Eastbound and Down Serasons 1 & 2 – 2 Espisodes Heart of Life - “Pilot” Good Behavior - “Episode - 202” Under The Dome - “Let the Games Begin” Legacies – 16 Episodes Lore - “Episode 102 “ The Glades - “Happy Trails” Black Lightning – Episode 201 The Vampire Diaries Seasons 1- 8 - 81 Episodes Revolution Season 1 - 2 Episodes MacGyver - 4 Episodes Sleepy Hollow Season 1-4 - 13 Episodes Burn Notice Season 1 & 6 - 3 Episodes Ozark Brockmire: Episode 104 Banshee -“Pilot” Good Girls – 3 Episodes Sun Records: Episode 101 & 108 Royal Pains -“Imperfect Storm” The Resident Season 1– 4 Episodes Untitled Paranormal Pilot Castle Rock Containment - 3 episodes The Originals Season 1-5 - 55 Episodes Vice Principals - “109” Kevin Probably Saves the World – 2 Episodes Complications - 6 episodes Valor – 2 Episodes Secrets and Lies Stunt -

School News Student Profiles Windows on Saint Mary’S Anniversary60th Contents

ALUMNI Volume 3 | No 2 MagnificatSaint Mary’s College Preparatory High School Alumni Association Magazine | Winter 2009 Wishing you a very blessed Christmas season and a New Year filled with peace & joy! IN THE SPOTLIGHT The Class of 1953: The First St. Mary’s High School Alumni Gaels Society Member Msgr. John J. McCann ‘57 SCHOOL NEWS Student Profiles Windows on Saint Mary’s Anniversary60th contents March 5-6, 2010 Sports Night sections Brother Kenneth Robert Gymnasium Doors open 7:30 PM | Showtime 8:00 PM alumni association | 5 March 11, 2010 Ladies’ Night Out: Boutique, Fashion Show and Dinner Leonard’s | Dolce Vita student profiles | 10 555 Northern Boulevard Great Neck, New York 6:30 PM Cocktails | 7:30 PM Dinner in the spotlight | 17 Join honorary Sports Night captains Sr. Mariette Quinn, IHM (White) and Mrs. Diane Papa (Blue) for a night of memories and school news | 18 tradition. Sponsored by the Gaels Parents’ Association. April 22, 2010 reunions | 24 60th Anniversary Celebration of St. Mary’s High School Plandome Country Club gael winds | 32 Plandome, New York 6:00 PM Cocktails & Buffet Dinner Join former faculty members, coaches, in memoriam | 38 administrators and classmates for a night celebrating the rich tradition and educational mission that has been St. Mary’s since its founding in 1949. Formal invitations to follow. April 24, 2010 Lacrosse Reunion Denihan Field All lacrosse alumni are invited to an alumni game and reception. Invitations to follow. On the Cover: One of the five blue gray terra cotta spandrels with life-sized scenes from the life of the Blessed Virgin fired in gold leaf on Immaculata September 23, 2010 Hall’s façade. -

The Originals: the Loss by Julie Plec

The Originals: The Loss by Julie Plec Ebook The Originals: The Loss currently available for review only, if you need complete ebook The Originals: The Loss please fill out registration form to access in our databases Download here >> Series:::: The Originals+++Paperback:::: 336 pages+++Publisher:::: HQN; Original edition (March 31, 2015)+++Language:::: English+++ISBN- 10:::: 0373788908+++ISBN-13:::: 978-0373788903+++Product Dimensions::::5.4 x 1 x 8.2 inches++++++ ISBN10 0373788908 ISBN13 978-0373788 Download here >> Description: Family is power. The Original vampire family swore it to each other a thousand years ago. They pledged to remain together always and forever. But even when youre immortal, promises are hard to keep.After a hurricane destroyed their city, Klaus, Elijah and Rebekah Mikaelson have rebuilt New Orleans to even greater glory. The year is 1766. The witches live on the fringes in the bayou. The werewolves have fled. But still, Klaus isnt satisfied. He wants more. He wants power. But when Klaus finally finds a witch who will perform a spell to give him what he desires most, she secretly uses Klaus to unleash a curse—one that brings back hundreds of her ancestors—and begins a war to reclaim New Orleans. As the siblings fight off the attack, only one things for certain—the result will be a bloodbath. I am a huge fan of the TV series and the two books in this series have followed the thread of the tv series. Someone who watches this series can picture what these siblings are doing and what they look like. -

JOSH RIFKIN Editor

JOSH RIFKIN Editor www.JoshRifkin.com Television PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. PARADISE LOST (season 1) Various Paramount Network / Anonymous Content VERONICA MARS (season 4) Various Hulu / Warner Bros. Television FOURSOME (seasons 1 + 4) Various YouTube Premium / AwesomenessTV TAKEN (season 2, 1 episode) Various NBC / EuropaCorp Television KNIGHTFALL (season 1)* Various History / A+E Studios BLACK SAILS (season 4)* Various Starz BAD BLOOD (mow) Adam Silver Lifetime / MarVista Entertainment STARVING IN SUBURBIA (mow) Tara Miele Lifetime / MarVista Entertainment SUMMER WITH CIMORELLI (digital series) Melanie Mayron YouTube Premium / AwesomenessTV KRISTIN’S CHRISTMAS PAST (mow) Jim Fall Lifetime / MarVista Entertainment LITTLE WOMEN, BIG CARS (digital - season 2) Melanie Mayron AOL / Awesomeness TV PRIVATE (digital series) Dennie Gordon Alloy Entertainment Additional Editor Feature Films PROJECT DIRECTOR STUDIO / PRODUCTION CO. SNAPSHOTS Melanie Mayron Gravitas Ventures Cast: Piper Laurie, Brett Dier, Brooke Adams Winner: Best Feature – 2018 Los Angeles Film Awards NINA Cynthia Mort Ealing Studios / RLJ Entertainment Cast: Zoe Saldana, David Oyelowo, Mike Epps MISSISSIPPI MURDER Price Hall Taylor & Dodge / Repertory Films Cast: Luke Goss, Malcolm McDowell, Bryan Batt MERCURY PLAINS Charles Burmeister Lionsgate / Carnaby Cast: Scott Eastwood, Andy Garcia, Nick Chinlund TRIPLE DOG Pascal Franchot Sierra / Affinity Cast: Britt Robertson, Alexia Fast NOT EASILY BROKEN Bill Duke Screen Gems Cast: Morris Chestnut, Taraji P. Henson, -

Michael Jackson, Acusado Formalmente|Pág

10245677 12/19/2003 12:06 a.m. Page 1 Espectáculos: Michael Jackson, acusado formalmente|Pág. 2 Viernes 19 de diciembre de 2003 B Editor: DINORA GONZÁLEZ Coeditores: JUAN LORENZO SIMENTAL VERÓNICA CASTRO Coeditor Gráfico: JESÚS ESPINOZA [email protected] ANTESALA | GONZÁLEZ IÑÁRRITU QUEDA FUERA FAMOSOS Nombres cotizados A continuación las principales ternas de los Globo de Oro: MEJOR PELÍCULA DRAMÁTICA ■ Cold Mountain Destapan ■ El Señor de los Anillos: El Retorno del Rey ■ Master and Commander: The Far Side of the World ■ Mystic River ■ Seabiscuit MEJOR ACTRIZ DRAMÁTICA ■ Cate Blanchett — Verónica Guerin ■ Nicole Kidman — Cold Mountain ■ Scarlett Johansson — Girl with a Pearl Earring favoritos ■ Charlize Theron — Monster ■ Uma Thurman — Kill Bill Vol. 1 Cold Mountain ■ Evan Rachel Wood — Thirteen arrasó con ocho MEJOR ACTOR DRAMÁTICO ■ Russell Crowe — Master and Commander nominaciones ■ Tom Cruise — El Último Samurai ■ Ben Kingsley — House of Sand and Fog a los Globo de Oro ■ Jude Law — Cold Mountain ■ Sean Penn — Mystic River Fotos: AP y Reuters | EL SIGLO DE DURANGO MEJOR PELÍCULA COMEDIA ■ Bend it Like Beckham BEVERLY HILLS, CALIFORNIA ■ Big Fish (REUTERS).- La película del ■ Buscando a Nemo director mexicano Alejan- ■ Lost in Translation dro González Iñárritu, 21 ■ Love Actually Gramos, fue excluida de las nominaciones al Globo MEJOR ACTRIZ COMEDIA O MUSICAL de Oro que ayer jueves ■ Jamie Lee Curtis — Freaky Friday fueron anunciadas. Scarlett Johansson. ■ Scarlett Johansson — Lost in Tanslation El drama de la Guerra ■ Diane Keaton — Something’s gotta Give de Secesión de Estados ■ Diane Lane — Under the Tuscan Sun Unidos Cold Mountain en- ■ Helen Mirren — Calendars Girls cabeza la lista de películas postuladas para los premios MEJOR ACTOR COMEDIA O MUSICAL Globo de Oro, con ocho no- ■ Jack Black — School of Rock minaciones, entre ellas en la ■ Johnny Depp — Piratas del Caribe: categoría de mejor filme. -

Appendix: Partial Filmographies for Lucile and Peggy Hamilton Adams

Appendix: Partial Filmographies for Lucile and Peggy Hamilton Adams The following is a list of films directly related to my research for this book. There is a more extensive list for Lucile in Randy Bryan Bigham, Lucile: Her Life by Design (San Francisco and Dallas: MacEvie Press Group, 2012). Lucile, Lady Duff Gordon The American Princess (Kalem, 1913, dir. Marshall Neilan) Our Mutual Girl (Mutual, 1914) serial, visit to Lucile’s dress shop in two episodes The Perils of Pauline (Pathé, 1914, dir. Louis Gasnier), serial The Theft of the Crown Jewels (Kalem, 1914) The High Road (Rolfe Photoplays, 1915, dir. John Noble) The Spendthrift (George Kleine, 1915, dir. Walter Edwin), one scene shot in Lucile’s dress shop and her models Hebe White, Phyllis, and Dolores all appear Gloria’s Romance (George Klein, 1916, dir. Colin Campbell), serial The Misleading Lady (Essanay Film Mfg. Corp., 1916, dir. Arthur Berthelet) Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (Mary Pickford Film Corp., 1917, dir. Marshall Neilan) The Rise of Susan (World Film Corp., 1916, dir. S.E.V. Taylor), serial The Strange Case of Mary Page (Essanay Film Manufacturing Company, 1916, dir. J. Charles Haydon), serial The Whirl of Life (Cort Film Corporation, 1915, dir. Oliver D. Bailey) Martha’s Vindication (Fine Arts Film Company, 1916, dir. Chester M. Franklin, Sydney Franklin) The High Cost of Living (J.R. Bray Studios, 1916, dir. Ashley Miller) Patria (International Film Service Company, 1916–17, dir. Jacques Jaccard), dressed Irene Castle The Little American (Mary Pickford Company, 1917, dir. Cecil B. DeMille) Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm (Mary Pickford Company, 1917, dir. -

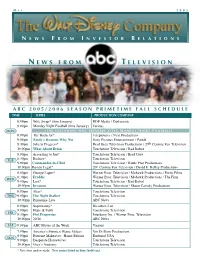

N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N

M A Y 2 0 0 5 N E W S F R O M I N V E S T O R R E L A T I O N S N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N A B C 2 0 0 5 / 2 0 0 6 S E A S O N P R I M E T I M E F A L L S C H E D U L E TIME SERIES PRODUCTION COMPANY 8:00pm Wife Swap* (thru January) RDF Media / Diplomatic 9:00pm Monday Night Football (thru January) Various MON ( T H E F O L L O W I N G W I L L P R E M I E R E A F T E R M O N D A Y N I G H T F O O T B A L L ) 8:00pm The Bachelor* Telepictures / Next Productions 9:00pm Emily’s Reasons Why Not Sony Pictures Entertainment / Pariah 9:30pm Jake in Progress* Brad Grey Television Productions / 20th Century Fox Television 10:00pm What About Brian Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 8:00pm According to Jim* Touchstone Television / Brad Grey 8:30pm Rodney* Touchstone Television TUE 9:00pm Commander-in-Chief Touchstone Television / Battle Plan Productions 10:00pm Boston Legal* 20th Century Fox Television / David E. Kelley Productions 8:00pm George Lopez* Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / Fortis Films 8:30pm Freddie Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / The Firm WED 9:00pm Lost* Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 10:00pm Invasion Warner Bros. -

Find PDF / the Originals: the Resurrection: Book 3 (Paperback)

DDZLSQFKU6OT » Doc » The Originals: The Resurrection: Book 3 (Paperback) Download Book THE ORIGINALS: THE RESURRECTION: BOOK 3 (PAPERBACK) Hachette Children s Group, United Kingdom, 2015. Paperback. Condition: New. Language: English . Brand New Book. As the oldest vampires in the world, Klaus, Elijah and Rebekah Mikaelson are less than thrilled that they must share New Orleans with the werewolves. Klaus decides to build an army to take them out once and for all. He s turning vampires left and right, with Rebekah by his side. The new vampires are killing any werewolf they can get their hands on,... Read PDF The Originals: The Resurrection: Book 3 (Paperback) Authored by Julie Plec Released at 2015 Filesize: 5.01 MB Reviews This ebook is fantastic. It is probably the most awesome book i actually have read. I found out this ebook from my i and dad suggested this book to understand. -- Ethel Mills I actually started reading this article ebook. I have got read and so i am certain that i will going to study once more yet again in the future. I am just very happy to inform you that this is the finest publication we have read in my personal lifestyle and may be he finest ebook for ever. -- Mrs. Clotilde Hansen II Unquestionably, this is the finest work by any publisher. I really could comprehended every little thing using this published e book. You will not sense monotony at anytime of your respective time (that's what catalogs are for regarding should you question me). -- Joe K essler TERMS | DMCA. -

Ryan Murphy As Curator of Queer Cultural Memory

ORIGINAL SCIENTIFIC PAPER 7.097:305-055.3 791.632-051 М АРФИ Р. DOI:10.5937/ ZRFFP47-14867 NIKOLA N. S TEPIĆ1 CONCORDIA U NIVERSITY CENTRE FOR I NTERDISCIPLINARY S TUDIES IN S OCIETY AND C ULTURE SPECTACLES OF SHAME: RYAN MURPHY AS CURATOR OF QUEER CULTURAL MEMORY ABSTRACT. In the anthology Queer Shame , edited by David M. Halperin and Valerie Traub, “the personal and the social shame attached to eroticism” is taken to task in relation to the larger contemporary discourse surrounding gay pride (understood in terms of activism and cultural production), while being seen as a defining characteristic of queer history, culture and identity. Shame, as theorized by Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Halperin and others, is predicated on a larger issue of queer people’s access to discursive power, which Sedgwick herself had theorized in The Epistemology of the Closet . Such a conceptual- izing of queer culture and queer politics begs the interrogation of how queer shame is contained and negotiated in contemporary popular culture. One of the most successful auteurs working in film and television today, Ryan Murphy’s opus is marked by a constant dialogue with queer cultural artifacts. The excitement that his productions generate is typically predicat- ed on his use of queer cultural objects, especially as they are rearticulated for mainstream audiences. This paper investigates the inherent shame of queer memory as embodied in Murphy’s show American Horror Story through ref- erence and negotiation of queer icons, filmic traditions and on-screen bodies. Utilizing queer and film theory as its framework, this paper treats Murphy’s queer vernacular as the uncanny that destabilizes conventions of both the horror genre and mainstream television, in turn legitimizing and ex- ploiting “shameful” queer categories such as trauma, excess, diva worship and camp through the language of popular television and the bodies that populate it. -

VAMPIRE DIARIES/ORIGINALS NASHVILLE SCHEDULE of EVENTS THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 2019

VAMPIRE DIARIES/ORIGINALS NASHVILLE SCHEDULE of EVENTS THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 7, 2019 NOTE: Pre-registration is not a necessity, just a convenience! Get your credentials, wristband and schedule so you don't have to wait again during convention days. VENDORS ROOM WILL BE OPEN TOO so you can get first crack at autograph and photo op tickets as well as merchandise! PRE-REGISTRATION IS ONLY FOR FULL CONVENTION ATTENDEES WITH EITHER GOLD, SILVER, COPPER OR GA WEEKEND. NOTE: If you have solo, duo or group photo ops with Ian, Paul, or Joseph please VALIDATE your pdf at the Photo Op Validation table BEFORE your photo op begins! START END EVENT LOCATION 3:30 PM 6:30 PM Vendors set-up Hermitage Foyer 6:30 PM 7:15 PM GOLD Pre-registration Hermitage Foyer 6:30 PM 8:45 PM VENDORS ROOM OPEN Hermitage Foyer 7:00 PM 9:00 PM GAME NIGHT with CHASE COLEMAN & MICAH PARKER! $99 Cheekwood 7:15 PM 7:45 PM SILVER Pre-registration Hermitage Foyer 7:45 PM 8:15 PM COPPER Pre-registration Hermitage Foyer 8:15 PM 8:45 PM GA WEEKEND Pre-registration plus GOLD, SILVER and COPPER Hermitage Foyer FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 8, 2019 *END TIMES ARE APPROXIMATE. PLEASE SHOW UP AT THE START TIME TO MAKE SURE YOU DON’T MISS ANYTHING! WE CANNOT GUARANTEE MISSED AUTOGRAPHS OR PHOTO OPS. Light Blue: Private meet & greets, Green: Autographs, Red: Theatre programming, Orange: VIP schedule, Purple: Photo ops, Dark Blue: Special Events Photo ops are on a first come, first served basis (unless you're a VIP or unless otherwise noted in the Photo op listing) Autographs for Gold/Silver are called row by row, then by those with their separate autographs, pre-purchased autographs are called first.