Ryan Murphy As Curator of Queer Cultural Memory

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Agnese Discusses Guns, Progress by Stephen M

VOL. 116. NO. 4 www.uiwlogos.org October 2015 Agnese discusses guns, progress By Stephen M. Sanchez LOGOS NEWS EDITOR The University of the Incarnate Word community will be polled to get its views on the state’s new law allowing concealed guns on campus but UIW will likely opt out, the president said. Dr. Louis J. Agnese Jr., who’s been president 30 years, shared this with those who attended his annual “State of the University” address on Oct. 6 at CHRISTUS Heritage Hall. Agnese also gave a mostly upbeat report on the university’s growth in his “Looking Ahead to 2020” PowerPoint presentation, pointing out how UIW has grown from 1,300 students and a budget of $8 mil- lion when he first became president in 1985 to its 11,000 students globally and budget in the hundreds of millions today. He’s seen a small college morph into the fourth-largest private school in the state and the largest Catholic institution in the state. UIW currently has 10 campuses in San Antonio, one in Corpus Christi, and another in Killeen. The university also contracts with 144 sister schools overseas in its Study Abroad program. More than 80 majors are offered including bachelor’s, master’s and doctoral degrees. UIW also has professional schools in pharmacy, optometry and physical therapy with a School of Osteopathic Medicine set to open in fall 2017 at Brooks City Base. UIW students also receive more than $150 million annually in financial aid. - Cont. on page 2 Stephen M. Sanchez/ LOGOS NEWS EDITOR -Agnese discusses progress. -

73Rd-Nominations-Facts-V2.Pdf

FACTS & FIGURES FOR 2021 NOMINATIONS as of July 13 does not includes producer nominations 73rd EMMY AWARDS updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page 1 of 20 SUMMARY OF MULTIPLE EMMY WINS IN 2020 Watchman - 11 Schitt’s Creek - 9 Succession - 7 The Mandalorian - 7 RuPaul’s Drag Race - 6 Saturday Night Live - 6 Last Week Tonight With John Oliver - 4 The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel - 4 Apollo 11 - 3 Cheer - 3 Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones - 3 Euphoria - 3 Genndy Tartakovsky’s Primal - 3 #FreeRayshawn - 2 Hollywood - 2 Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: “All In The Family” And “Good Times” - 2 The Cave - 2 The Crown - 2 The Oscars - 2 PARTIAL LIST OF 2020 WINNERS PROGRAMS: Comedy Series: Schitt’s Creek Drama Series: Succession Limited Series: Watchman Television Movie: Bad Education Reality-Competition Program: RuPaul’s Drag Race Variety Series (Talk): Last Week Tonight With John Oliver Variety Series (Sketch): Saturday Night Live PERFORMERS: Comedy Series: Lead Actress: Catherine O’Hara (Schitt’s Creek) Lead Actor: Eugene Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actress: Annie Murphy (Schitt’s Creek) Supporting Actor: Daniel Levy (Schitt’s Creek) Drama Series: Lead Actress: Zendaya (Euphoria) Lead Actor: Jeremy Strong (Succession) Supporting Actress: Julia Garner (Ozark) Supporting Actor: Billy Crudup (The Morning Show) Limited Series/Movie: Lead Actress: Regina King (Watchman) Lead Actor: Mark Ruffalo (I Know This Much Is True) Supporting Actress: Uzo Aduba (Mrs. America) Supporting Actor: Yahya Abdul-Mateen II (Watchmen) updated 07.13.2021 version 1 Page -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 90Th Academy Awards Alien

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 90TH ACADEMY AWARDS ALIEN: COVENANT Actors: Michael Fassbender. Billy Crudup. Danny McBride. Demian Bichir. Jussie Smollett. Nathaniel Dean. Alexander England. Benjamin Rigby. Uli Latukefu. Goran D. Kleut. Actresses: Katherine Waterston. Carmen Ejogo. Callie Hernandez. Amy Seimetz. Tess Haubrich. Lorelei King. ALL I SEE IS YOU Actors: Jason Clarke. Wes Chatham. Danny Huston. Actresses: Blake Lively. Ahna O'Reilly. Yvonne Strahovski. ALL THE MONEY IN THE WORLD Actors: Christopher Plummer. Mark Wahlberg. Romain Duris. Timothy Hutton. Charlie Plummer. Charlie Shotwell. Andrew Buchan. Marco Leonardi. Giuseppe Bonifati. Nicolas Vaporidis. Actresses: Michelle Williams. ALL THESE SLEEPLESS NIGHTS AMERICAN ASSASSIN Actors: Dylan O'Brien. Michael Keaton. David Suchet. Navid Negahban. Scott Adkins. Taylor Kitsch. Actresses: Sanaa Lathan. Shiva Negar. AMERICAN MADE Actors: Tom Cruise. Domhnall Gleeson. Actresses: Sarah Wright. AND THE WINNER ISN'T ANNABELLE: CREATION Actors: Anthony LaPaglia. Brad Greenquist. Mark Bramhall. Joseph Bishara. Adam Bartley. Brian Howe. Ward Horton. Fred Tatasciore. Actresses: Stephanie Sigman. Talitha Bateman. Lulu Wilson. Miranda Otto. Grace Fulton. Philippa Coulthard. Samara Lee. Tayler Buck. Lou Lou Safran. Alicia Vela-Bailey. ARCHITECTS OF DENIAL ATOMIC BLONDE Actors: James McAvoy. John Goodman. Til Schweiger. Eddie Marsan. Toby Jones. Actresses: Charlize Theron. Sofia Boutella. 90th Academy Awards Page 1 of 34 AZIMUTH Actors: Sammy Sheik. Yiftach Klein. Actresses: Naama Preis. Samar Qupty. BPM (BEATS PER MINUTE) Actors: 1DKXHO 3«UH] %LVFD\DUW $UQDXG 9DORLV $QWRLQH 5HLQDUW] )«OL[ 0DULWDXG 0«GKL 7RXU« Actresses: $GªOH +DHQHO THE B-SIDE: ELSA DORFMAN'S PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHY BABY DRIVER Actors: Ansel Elgort. Kevin Spacey. Jon Bernthal. Jon Hamm. Jamie Foxx. -

Hbo Premieres Original Drama Film the Normal Heart

HBO PREMIERES ORIGINAL DRAMA FILM “THE NORMAL HEART” Broadway run, and directed by Emmy® winner Ryan Murphy, the powerful film tells the story of the rise of the HIV-AIDS crisis in New York in the early 80’s. It takes an unflinching look at the nation’s sexual politics as gay activists and their allies in the medical community fought to expose the truth about the burgeoning epidemic to a city and nation in denial. The Normal Heart brings together a cast of talented actors, including Mark Ruffalo as Ned Weeks, a gay writer looking for answers as he witnesses how the mysterious illness begins to take a heavy toll on the gay community; Matt Bomer as Felix Turner, a reporter who becomes Ned’s lover; Taylor Kitsch as Bruce Niles, a closeted investment banker who becomes a prominent AIDS activist; Emmy® winner Jim Parsons as activist Tommy Boatwright, the same role he played on the Broadway version in 2011; and for the first time in an HBO production, Julia Roberts as Dr. Emma Brookner, a childhood survivor of polio who treats many of the early victims of HIV-AIDS. The drama also stars Alfred Molina in the role of Ben, a successful attorney and Ned’s older brother; Tony® winner Joe Mantello as Mickey Marcus; Jonathan Groff (HBO’s “Looking”) as Craig; Denis O’Hare (HBO’s “True Blood”) as Hiram Keebler; Stephen Spinella as Sanford; Corey Stoll as John Bower; Finn Wittrock as Albert; and BD Wong (HBO’s “Oz”) as Buzzy. The Normal Heart was directed by Ryan Murphy (“Eat, Pray, Love” and “Glee”); written by Larry Kramer; executive produced by Murphy, Dante Di Loreto, Jason Blum, Brad Pitt and Dede Gardner; co-executive produced by Ruffalo; and produced by Scott Ferguson (HBO’s “Temple Grandin”). -

Download Epk (Pdf)

CRYPTO PRODUCTION NOTES For additional publicity materials and artwork, please visit: http://lionsgatepublicity.com/theatrical/crypto/ Rating: R for language throughout, some violence, sexuality and drug use Running Time: 105 Minutes U.S. Release Date: In Select Theaters and On Demand April 12, 2019 For more information, please contact: Amy Utley Danny Duran Lionsgate ddPR [email protected] [email protected] CRYPTO LIONSGATE Trailer: https://youtu.be/_tbY8gclLYY Publicity Materials: www.lionsgatepublicity.com/theatrical/crypto/ Genre: Thriller Rating: R for language throughout, some violence, sexuality and drug use Copyright: © 2018 Examiner the Movie, LLC. All Rights Reserved. U.S. Release Date: April 12, 2019 (Theatrical and On Demand) Run Time: 105 Minutes Cast: Beau Knapp (Martin Duran, Jr.), Alexis Bledel (Katie), Luke Hemsworth (Caleb Duran), Jeremie Harris (Earl Simmons), Jill Hennessy (Robin Whiting), Malaya Rivera Drew (Penelope Rushing), with Vincent Kartheiser (Ted Patterson) and Kurt Russell (Martin Duran, Sr.) Directed by: John Stalberg Jr. Written by: Carlyle Eubank & David Frigerio Story by: Jeffrey Ingber Produced by: Jordan Yale Levine Jordan Beckerman David Frigerio Director of Photography: Pieter Vermeer Production Designer: Eric Whitney Editor: Brian Berdan, ACE Costume Designer: Annie Simon Sound Design by: Flavorlab Music by: Nima Fakhrara Casting by: Brandon Henry Rodriguez, CSA Film by: John Stalberg Jr. Credits not contractual SYNOPSIS In this cyber-thriller starring Kurt Russell and Beau Knapp, a Wall Street banker connects a small-town art gallery to a global conspiracy, putting his own family in grave danger. DIRECTOR’S STATEMENT I love the moment in film when the mundane morphs suddenly into menace—when people who believe they fit into their worlds suddenly, sometimes violently—no longer do. -

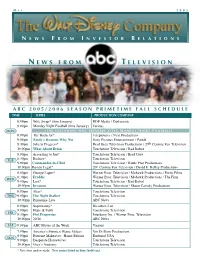

N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N

M A Y 2 0 0 5 N E W S F R O M I N V E S T O R R E L A T I O N S N E W S F R O M T E L E V I S I O N A B C 2 0 0 5 / 2 0 0 6 S E A S O N P R I M E T I M E F A L L S C H E D U L E TIME SERIES PRODUCTION COMPANY 8:00pm Wife Swap* (thru January) RDF Media / Diplomatic 9:00pm Monday Night Football (thru January) Various MON ( T H E F O L L O W I N G W I L L P R E M I E R E A F T E R M O N D A Y N I G H T F O O T B A L L ) 8:00pm The Bachelor* Telepictures / Next Productions 9:00pm Emily’s Reasons Why Not Sony Pictures Entertainment / Pariah 9:30pm Jake in Progress* Brad Grey Television Productions / 20th Century Fox Television 10:00pm What About Brian Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 8:00pm According to Jim* Touchstone Television / Brad Grey 8:30pm Rodney* Touchstone Television TUE 9:00pm Commander-in-Chief Touchstone Television / Battle Plan Productions 10:00pm Boston Legal* 20th Century Fox Television / David E. Kelley Productions 8:00pm George Lopez* Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / Fortis Films 8:30pm Freddie Warner Bros. Television / Mohawk Productions / The Firm WED 9:00pm Lost* Touchstone Television / Bad Robot 10:00pm Invasion Warner Bros. -

Reminder List of Productions Eligible for the 88Th Academy Awards

REMINDER LIST OF PRODUCTIONS ELIGIBLE FOR THE 88TH ACADEMY AWARDS ADULT BEGINNERS Actors: Nick Kroll. Bobby Cannavale. Matthew Paddock. Caleb Paddock. Joel McHale. Jason Mantzoukas. Mike Birbiglia. Bobby Moynihan. Actresses: Rose Byrne. Jane Krakowski. AFTER WORDS Actors: Óscar Jaenada. Actresses: Marcia Gay Harden. Jenna Ortega. THE AGE OF ADALINE Actors: Michiel Huisman. Harrison Ford. Actresses: Blake Lively. Kathy Baker. Ellen Burstyn. ALLELUIA Actors: Laurent Lucas. Actresses: Lola Dueñas. ALOFT Actors: Cillian Murphy. Zen McGrath. Winta McGrath. Peter McRobbie. Ian Tracey. William Shimell. Andy Murray. Actresses: Jennifer Connelly. Mélanie Laurent. Oona Chaplin. ALOHA Actors: Bradley Cooper. Bill Murray. John Krasinski. Danny McBride. Alec Baldwin. Bill Camp. Actresses: Emma Stone. Rachel McAdams. ALTERED MINDS Actors: Judd Hirsch. Ryan O'Nan. C. S. Lee. Joseph Lyle Taylor. Actresses: Caroline Lagerfelt. Jaime Ray Newman. ALVIN AND THE CHIPMUNKS: THE ROAD CHIP Actors: Jason Lee. Tony Hale. Josh Green. Flula Borg. Eddie Steeples. Justin Long. Matthew Gray Gubler. Jesse McCartney. José D. Xuconoxtli, Jr.. Actresses: Kimberly Williams-Paisley. Bella Thorne. Uzo Aduba. Retta. Kaley Cuoco. Anna Faris. Christina Applegate. Jennifer Coolidge. Jesica Ahlberg. Denitra Isler. 88th Academy Awards Page 1 of 32 AMERICAN ULTRA Actors: Jesse Eisenberg. Topher Grace. Walton Goggins. John Leguizamo. Bill Pullman. Tony Hale. Actresses: Kristen Stewart. Connie Britton. AMY ANOMALISA Actors: Tom Noonan. David Thewlis. Actresses: Jennifer Jason Leigh. ANT-MAN Actors: Paul Rudd. Corey Stoll. Bobby Cannavale. Michael Peña. Tip "T.I." Harris. Anthony Mackie. Wood Harris. David Dastmalchian. Martin Donovan. Michael Douglas. Actresses: Evangeline Lilly. Judy Greer. Abby Ryder Fortson. Hayley Atwell. ARDOR Actors: Gael García Bernal. Claudio Tolcachir. -

The Not-So-Spectacular Now by Gabriel Broshy

cinemann The State of the Industry Issue Cinemann Vol. IX, Issue 1 Fall/Winter 2013-2014 Letter from the Editor From the ashes a fire shall be woken, A light from the shadows shall spring; Renewed shall be blade that was broken, The crownless again shall be king. - Recited by Arwen in Peter Jackson’s adaption of the final installment ofThe Lord of the Rings Trilogy, The Return of the King, as her father prepares to reforge the shards of Narsil for Ara- gorn This year, we have a completely new board and fantastic ideas related to the worlds of cinema and television. Our focus this issue is on the states of the industries, highlighting who gets the money you pay at your local theater, the positive and negative aspects of illegal streaming, this past summer’s blockbuster flops, NBC’s recent changes to its Thursday night lineup, and many more relevant issues you may not know about as much you think you do. Of course, we also have our previews, such as American Horror Story’s third season, and our reviews, à la Break- ing Bad’s finale. So if you’re interested in the movie industry or just want to know ifGravity deserves all the fuss everyone’s been having about it, jump in! See you at the theaters, Josh Arnon Editor-in-Chief Editor-in-Chief Senior Content Editor Design Editors Faculty Advisor Josh Arnon Danny Ehrlich Allison Chang Dr. Deborah Kassel Anne Rosenblatt Junior Content Editor Kenneth Shinozuka 2 Table of Contents Features The Conundrum that is Ben Affleck Page 4 Maddie Bender How Real is Reality TV? Page 6 Chase Kauder Launching -

70Th Emmy Awards Nominations Announcements July 12, 2018 (A Complete List of Nominations, Supplemental Facts and Figures May Be Found at Emmys.Com)

70th Emmy Awards Nominations Announcements July 12, 2018 (A complete list of nominations, supplemental facts and figures may be found at Emmys.com) Emmy Nominations Previous Wins 70th Emmy Nominee Program Network to date to date Nominations Total (across all categories) (across all categories) LEAD ACTRESS IN A DRAMA SERIES Claire Foy The Crown Netflix 1 2 0 Tatiana Maslany Orphan Black BBC America 1 3 1 Elisabeth Moss The Handmaid's Tale Hulu 1 10 2 Sandra Oh Killing Eve BBC America 1 6 0 Keri Russell The Americans FX Networks 1 3 0 Evan Rachel Wood Westworld HBO 1 3 0 LEAD ACTOR IN A DRAMA SERIES Jason Bateman Ozark Netflix 2* 4 0 Sterling K. Brown This Is Us NBC 2* 4 2 Ed Harris Westworld HBO 1 3 0 Matthew Rhys The Americans FX Networks 1 4 0 Milo Ventimiglia This Is Us NBC 1 2 0 Jeffrey Wright Westworld HBO 1 3 1 * NOTE: Jason Bateman also nominated for Directing for Ozark * NOTE: Sterling K. Brown also nominated for Guest Actor in a Comedy Series for Brooklyn Nine-Nine LEAD ACTRESS IN A COMEDY SERIES Pamela Adlon Better Things FX Networks 1 7 1 Rachel Brosnahan The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel Prime Video 1 2 0 Allison Janney Mom CBS 1 14 7 Issa Rae Insecure HBO 1 1 NA Tracee Ellis Ross black-ish ABC 1 3 0 Lily Tomlin Grace And Frankie Netflix 1 25 6 LEAD ACTOR IN A COMEDY SERIES Anthony Anderson black-ish ABC 1 6 0 Ted Danson The Good Place NBC 1 16 2 Larry David Curb Your Enthusiasm HBO 1 26 2 Donald Glover Atlanta FX Networks 4* 8 2 Bill Hader Barry HBO 4* 14 1 William H. -

Youtube Wipes Billions of Video Views After Finding They Had Been 'Faked by the Music Industry' | Daily Mail Online 24.03.2021, 23:47

YouTube wipes billions of video views after finding they had been 'faked by the music industry' | Daily Mail Online 24.03.2021, 23:47 Privacy Policy Feedback Wednesday, Mar 24th 2021 Home U.K. News Sports U.S. Showbiz Australia Femail Health Science Money Video Latest Headlines NASA Apple Twitter Games YouTube cancels billions of music Site industry video views after finding they were fake or 'dead' Major record labels stripped of more than two billion video views Biggest hit taken by Universal, which alone lost more than one billion 'This was an enforcement of our viewcount policy,' says YouTube By DAMIEN GAYLE PUBLISHED: 07:58 EDT, 28 December 2012 | UPDATED: 03:17 EDT, 31 December 2012 183 View comments The world's biggest recording companies have been stripped of two billion YouTube hits after the website https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-2254181/YouTube-wipes-billions-video-views-finding-faked-music-industry.html Page 1 of 35 YouTube wipes billions of video views after finding they had been 'faked by the music industry' | Daily Mail Online 24.03.2021, 23:47 billion YouTube hits after the website Download our cracked down on alleged 'fake' and iPhone app +99 'dead' views. NEW ARTICLES Top Today's headlines Universal, home of Rihanna, Nicki Minaj and Justin Bieber, lost a total of one Share billion views in the video site’s biggest ever crackdown on its viewing figures. Sony was second hardest hit, with the label behind such stars as Alicia Keys, Rita Ora and Labrinth losing more than 850million views in a single day. -

Spring 2020 New RELEASES © 2020 Paramount Pictures 2020 © © 2020 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc

Spring 2020 New RELEASES © 2020 Paramount Pictures 2020 © © 2020 Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. All Rights Reserved. © 2020 Universal City Studios Productions LLLP. © Lions Entertainment, Gate © Inc. © 2020 Disney Enterprises Inc. Bros. Ent. All rights reserved. © 2020 Warner swank.com/motorcoaches 10795 Watson Road 1.888.416.2572 St. Louis, MO 63127 MovieRATINGS GUIDE G/PG: Midway ............................. Page 19 Nightingale, The.............. Page 21 Peanut Butter Ode to Joy ........................ Page 18 Abominable .........................Page 7 Falcon, The ..........................Page 4 Official Secrets ................ Page 14 Addams Family, The ..........Page 5 Scary Stories to Tell in the Dark ................ Page 12 Once Upon a Time Angry Birds in Hollywood ......................Page 9 Movie 2, The .......................Page 4 Super Size Me 2: Holy Chicken ................... Page 15 One Child Nation ...............Page 9 Arctic Dogs .........................Page 7 Where'd You Go, Parasite ............................. Page 15 Beautiful Day in the Bernadette ..........................Page 6 Neighborhood, A ...............Page 3 Queen & Slim ................... Page 13 Dora and the Lost Rambo: Last Blood ............Page 9 City of Gold .........................Page 9 Report, The ...................... Page 14 Downton Abbey ............. Page 14 R: Terminator: Farewell, The ................... Page 12 21 Bridges ........................ Page 10 Dark Fate .............................Page 3 Frozen II ...............................Page -

TH256-15 Adapting Shakespeare for Performance

TH256-15 Adapting Shakespeare for Performance 21/22 Department Theatre and Performance Studies Level Undergraduate Level 2 Module leader Ronan Hatfull Credit value 15 Module duration 10 weeks Assessment 100% coursework Study location University of Warwick main campus, Coventry Description Introductory description Adapting Shakespeare for Peformance is a practice-based module that invites students to engage in the adaptation process and produce their own creative responses to the plays of William Shakespeare. This module will challenge students to produce their own interpretation of plays which have helped shape how adaptation is received and practiced. An intrinsic part of Shakespeare’s legacy is the adaptation of his work on stage, page and screen. Shakespeare himself was a consummate adapter, drawing on pre-existing literary and theatrical materials and re-working these for his audiences, for whom his plays were a form of popular entertainment. How is Shakespeare reconceptualised in the context of popular culture and what methods do modern artists use to render his work accessible? This module will challenge the perception of what can be perceived as an adaptation of Shakespeare and each 180-minute workshop will involve practical exploration of different media, including poetry, prose, film, television and theatre. Students will be asked to create a three-minute mini-adaptation/pitch in response to each week’s material and asked to present this at the following seminar. Using this accumulative creative material and case studies as models, the module will culminate with the creation of group adaptations, which will be rehearsed in Weeks 8 and 9 and presented during Week 10.