4 the Life of the Gladiator

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lord Lyon King of Arms

VI. E FEUDAE BOBETH TH F O LS BABONAG F SCOTLANDO E . BY THOMAS INNES OP LEABNEY AND KINNAIRDY, F.S.A.ScoT., LORD LYON KIN ARMSF GO . Read October 27, 1945. The Baronage is an Order derived partly from the allodial system of territorial tribalis whicn mi patriarce hth h hel s countrydhi "under God", d partlan y froe latemth r feudal system—whic e shale wasw hse n li , Western Europe at any rate, itself a developed form of tribalism—in which the territory came to be held "of and under" the King (i.e. "head of the kindred") in an organised parental realm. The robes and insignia of the Baronage will be found to trace back to both these forms of tenure, which first require some examination from angle t usuallno s y co-ordinatedf i , the later insignia (not to add, the writer thinks, some of even the earlier understoode symbolsb o t e )ar . Feudalism has aptly been described as "the development, the extension organisatione th y sa y e Family",o familyth fma e oe th f on n r i upon,2o d an Scotlandrelationn i Land;e d th , an to fundamentall o s , tribaa y l country, wher e predominanth e t influences have consistently been Tribality and Inheritance,3 the feudal system was immensely popular, took root as a means of consolidating and preserving the earlier clannish institutions,4 e clan-systeth d an m itself was s modera , n historian recognisew no s t no , only closely intermingled with feudalism, but that clan-system was "feudal in the strictly historical sense".5 1 Stavanger Museums Aarshefle, 1016. -

VESPASIAN. AD 68, Though Not a Particularly Constructive Year For

138 VESPASIAN. AD 68, though not a particularly constructive year for Nero, was to prove fertile ground for senators lion the make". Not that they were to have the time to build anything much other than to carve out a niche for themselves in the annals of history. It was not until the dust finally settled, leaving Vespasian as the last contender standing, that any major building projects were to be initiated under Imperial auspices. However, that does not mean that there is nothing in this period that is of interest to this study. Though Galba, Otho and Vitellius may have had little opportunity to indulge in any significant building activity, and probably given the length and nature of their reigns even less opportunity to consider the possibility of building for their future glory, they did however at the very least use the existing imperial buildings to their own ends, in their own ways continuing what were by now the deeply rooted traditions of the principate. Galba installed himself in what Suetonius terms the palatium (Suet. Galba. 18), which may not necessarily have been the Golden House of Nero, but was part at least of the by now agglomerated sprawl of Imperial residences in Rome that stretched from the summit of the Palatine hill across the valley where now stands the Colosseum to the slopes of the Oppian, and included the Golden House. Vitellius too is said to have used the palatium as his base in Rome (Suet. Vito 16), 139 and is shown by Suetonius to have actively allied himself with Nero's obviously still popular memory (Suet. -

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad An extract from the Irish Sport Horse Studbook Stallion Book The Irish Sport Horse Studbook is maintained by Horse Sport Ireland and the Northern Ireland Horse Board Horse Sport Ireland First Floor, Beech House, Millennium Park, Osberstown, Naas, Co. Kildare, Ireland Telephone: 045 850800. Int: +353 45 850800 Fax: 045 850850. Int: +353 45 850850 Email: [email protected] Website: www.horsesportireland.ie Northern Ireland Horse Board Office Suite, Meadows Equestrian Centre Embankment Road, Lurgan Co. Armagh, BT66 6NE, Northern Ireland Telephone: 028 38 343355 Fax: 028 38 325332 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nihorseboard.org Copyright © Horse Sport Ireland 2015 HIGH PERFORMANCE STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD INDEX OF APPROVED STALLIONS BY BREED HIGH PERFORMANCE RECOGNISED FOREIGN BREED STALLIONS & STALLIONS STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD & ACANTUS GK....................................4 APPROVED THROUGH AI ACTION BREAKER.............................4 BALLOON [GBR] .............................10 KROONGRAAF............................... 62 AIR JORDAN Z.................................. 5 CANABIS Z......................................18 LAGON DE L'ABBAYE..................... 63 ALLIGATOR FONTAINE..................... 6 CANTURO.......................................19 LANDJUWEEL ST. HUBERT ............ 64 AMARETTO DARCO ......................... 7 CASALL LA SILLA.............................22 LARINO.......................................... 66 -

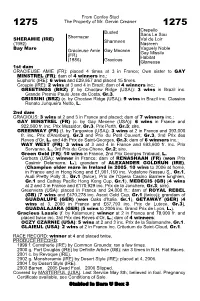

From Confey Stud the Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner Busted

From Confey Stud 1275 The Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner 1275 Crepello Busted Sans Le Sou Shernazar Val de Loir SHERAMIE (IRE) Sharmeen (1992) Nasreen Bay Mare Vaguely Noble Gracieuse Amie Gay Mecene Gay Missile (FR) Habitat (1986) Gracious Glaneuse 1st dam GRACIEUSE AMIE (FR): placed 4 times at 3 in France; Own sister to GAY MINSTREL (FR); dam of 4 winners inc.: Euphoric (IRE): 6 wins and £29,957 and placed 15 times. Groupie (IRE): 2 wins at 3 and 4 in Brazil; dam of 4 winners inc.: GREETINGS (BRZ) (f. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 3 wins in Brazil inc. Grande Premio Paulo Jose da Costa, Gr.3. GRISSINI (BRZ) (c. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 9 wins in Brazil inc. Classico Renato Junqueira Netto, L. 2nd dam GRACIOUS: 3 wins at 2 and 3 in France and placed; dam of 7 winners inc.: GAY MINSTREL (FR) (c. by Gay Mecene (USA)): 6 wins in France and 922,500 fr. inc. Prix Messidor, Gr.3, Prix Perth, Gr.3; sire. GREENWAY (FR) (f. by Targowice (USA)): 3 wins at 2 in France and 393,000 fr. inc. Prix d'Arenberg, Gr.3 and Prix du Petit Couvert, Gr.3, 2nd Prix des Reves d'Or, L. and 4th Prix de Saint-Georges, Gr.3; dam of 6 winners inc.: WAY WEST (FR): 3 wins at 3 and 4 in France and 693,600 fr. inc. Prix Servanne, L., 3rd Prix du Gros-Chene, Gr.2; sire. Green Gold (FR): 10 wins in France, 2nd Prix Georges Trabaud, L. Gerbera (USA): winner in France; dam of RENASHAAN (FR) (won Prix Casimir Delamarre, L.); grandam of ALEXANDER GOLDRUN (IRE), (Champion older mare in Ireland in 2005, 10 wins to 2006 at home, in France and in Hong Kong and £1,901,150 inc. -

The Grave Goods of Roman Hierapolis

THE GRAVE GOODS OF ROMAN HIERAPOLIS AN ANALYSIS OF THE FINDS FROM FOUR MULTIPLE BURIAL TOMBS Hallvard Indgjerd Department of Archaeology, Conservation and History University of Oslo This thesis is submitted for the degree of Master of Arts June 2014 The Grave Goods of Roman Hierapolis ABSTRACT The Hellenistic and Roman city of Hierapolis in Phrygia, South-Western Asia Minor, boasts one of the largest necropoleis known from the Roman world. While the grave monuments have seen long-lasting interest, few funerary contexts have been subject to excavation and publication. The present study analyses the artefact finds from four tombs, investigating the context of grave gifts and funerary practices with focus on the Roman imperial period. It considers to what extent the finds influence and reflect varying identities of Hierapolitan individuals over time. Combined, the tombs use cover more than 1500 years, paralleling the life-span of the city itself. Although the material is far too small to give a conclusive view of funerary assem- blages in Hierapolis, the attempted close study and contextual integration of the objects does yield some results with implications for further studies of funerary contexts on the site and in the wider region. The use of standard grave goods items, such as unguentaria, lamps and coins, is found to peak in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD. Clay unguentaria were used alongside glass ones more than a century longer than what is usually seen outside of Asia Minor, and this period saw the development of new forms, partially resembling Hellenistic types. Some burials did not include any grave gifts, and none were extraordinarily rich, pointing towards a standardised, minimalistic set of funerary objects. -

Gladiator Politics from Cicero to the White House

Gladiator Politics from Cicero to the White House The gladiator has become a popular icon. He is the hero fighting against the forces of oppression, a Spartacus or a Maximus. He is the "gridiron gladiator" of Monday night football. But he is also the politician on the campaign trail. The casting of the modern politician as gladiator both appropriates and transforms ancient Roman attitudes about gladiators. Ancient gladiators had a certain celebrity, but they were generally identified as infames and antithetical to the behavior and values of Roman citizens. Gladiatorial associations were cast as slurs against one's political opponents. For example, Cicero repeatedly identifies his nemesis P. Clodius Pulcher as a gladiator and accuses him of using gladiators to compel political support in the forum by means of violence and bloodshed in the Pro Sestio. In the 2008 and 2012 presidential campaigns the identification of candidates as gladiators reflects a greater complexity of the gladiator as a modern cultural symbol than is reflected by popular film portrayals and sports references. Obama and Clinton were compared positively to "two gladiators who have been at it, both admired for sticking at it" in their "spectacle" of a debate on February 26, 2008 by Tom Ashbrook and Mike McIntyre on NPR's On Point. Romney and Gingrich appeared on the cover of the February 6, 2012 issue of Newsweek as gladiators engaged in combat, Gingrich preparing to stab Romney in the back. These and other examples of political gladiators serve, when compared to texts such as Cicero's Pro Sestio, as a means to examine an ancient cultural phenomenon and modern, popularizing appropriations of that phenomenon. -

Daily Iowan (Iowa City, Iowa), 1955-12-16

... Servillg The State Iliversity of Iowa Camp« arullowa City Established in 1868~f'lv e Cents a Copy ~em~r of Associated Pr Wire and Wirephoto Service Iowa City. Jowa. Friday. Decem~r 16. 1955 All Eyes and Ears ~ ' ATO Lays Plans ISU'I Keeps Core For ·Radar System PARIS (JP)-Western statesmen decided Thursday to construct a • lIolfiM air raid warn in, screen from Norway acro" Europe to Tur ke.Y. backed by a new jam-proof communications net. , The United States will pay for the beginnlnll of thl Installation. Tbe foreign, finance and defense ministers of thc North Atlantic C:otJ"rse Revi slon Treaty Organization tOQk this step on an urient report form U.S. ~retary o( State John Foster ----- Vulles that the Soviet Union has I ( reopenoci the cold war. owa Tested Plan NATO's own military manners I'ly The Weather blclled Dulles with a warnin, that the Russian military threat Ex-Mayor Inlo Eftecl Is greater now than ever before. , 'tclal I. T"~ Dalb 1..... , Clear Tbe Soviets now have speedy jet WILMINGTON, Del. - Du Pont Company thu"day nnouneed a IT nt of more th n S9oo,OOO to over 100 unlversitles Ind colL , bombers capable of blasting any DileS at 72 rOt ~he n xt IC demlc year. & In September ,art of the NATO area with tre- UI is on of 20 universltie to r ive $1,~0 to be awarded io JDendous nuclear explosives. youn . r taC! m mbers of the ehemSatry department for r B, GENE INGLE work durin the summer of 1956. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

^Sehorse Junior Awmg British Breeders

s 8 4 THE NEW YORK HERALD>, SUNDAY, JUNE 18, 1922. ! AMAZING RECORDS <CYLLENE'S PLACE ILatest News and Gossip ARMY TO COMPETE MORVICH'S RIVALS OF A8TOR RACERS AS RACING SIRE' About the Horse Shows FOR POLO HONORS> IN $60,000RACE <$, ...... r.* ' s and Owners of Snob and BLUE FRONTf Jl Expatriated American His Descendants Predominate Press Agent's Occupation Is I Running Meetings Horses Players Arriving Pillory, the Man of the Hour in Turf Glassies Gone as Promoter of n * I 1 t <a nnn on I*>n£ Island to Train for Others Hopeful of Winning SALES Horseman England's to De neia m i f $^sehorse Junior Awmg British Breeders. This Season. Exhibits. PublicityCovington, Ky June (i-July 8 Championships. Kentucky Special. STABLESI IkW AUCTIONS Muntrcul, ( tin June bo(4 LEXINGTON Aqurdurl, N. Y Juno 10-July 7 24 Street Ty TP THIRD AVE. llnmUtun, Cun .June SU-July 3 rACTGKs IN THiF The prominence of the blocH of By G. CHAPLIN. I. Curt Krir. Cnu July 4-U About fifty polo horses will be Need of such a turf test as the 150,000 OLASSTCix I tankers, N. Y luty H-3U at »ije Mlneola fair grounds assembledon Kentucky Special, a scale weight race of "The Recognized Eastern Disbributkig Centre for Horses" ti.e winners and contoiaderaCyl!nof Tho scarcity of show horses la leading i Windsor, Can July 13-80 Island this week 15 Hnniiltun, Can July 31-Aug. 7 Uong for the use of one mile and a quarter, to be run next i he classic races in England this season to some queer practices this season In United States Army officers who are Saratoga. -

Building in Early Medieval Rome, 500-1000 AD

BUILDING IN EARLY MEDIEVAL ROME, 500 - 1000 AD Robert Coates-Stephens PhD, Archaeology Institute of Archaeology, University College London ProQuest Number: 10017236 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10017236 Published by ProQuest LLC(2016). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Abstract The thesis concerns the organisation and typology of building construction in Rome during the period 500 - 1000 AD. Part 1 - the organisation - contains three chapters on: ( 1) the finance and administration of building; ( 2 ) the materials of construction; and (3) the workforce (including here architects and architectural tracts). Part 2 - the typology - again contains three chapters on: ( 1) ecclesiastical architecture; ( 2 ) fortifications and aqueducts; and (3) domestic architecture. Using textual sources from the period (papal registers, property deeds, technical tracts and historical works), archaeological data from the Renaissance to the present day, and much new archaeological survey-work carried out in Rome and the surrounding country, I have outlined a new model for the development of architecture in the period. This emphasises the periods directly preceding and succeeding the age of the so-called "Carolingian Renaissance", pointing out new evidence for the architectural activity in these supposed dark ages. -

1 Ever Since First Reading About Female Gladiators, the Concept and Details

Ever since first reading about female gladiators, the concept and details behind such “woman warriors” has continued to fascinate me. While there are fewer primary sources that discuss female gladiators and their involvement in the arena, the sources I did locate helped me compile an interesting insight into the potential life of a female gladiator. I decided to direct my focus on a woman of the upper, elite class becoming a gladiator because I believe that “transformation” from femina (a woman of upper class status) to gladiator is more interesting than a woman of lower status making the choice to fight in the arena. I draw evidence from two books: Gladiatrix: The True Story of History’s Unknown Woman Warrior by Amy Zoll, and Women in Ancient Rome: A Sourcebook by Bonnie Maclachlan. I also cite two scholarly articles: “Female Gladiators in Imperial Rome: Literary Context and Historical Fact” by Anna McCollough, and “New Evidence of Female Gladiators” by Alfanso Manas, and I utilize three readings from class, including: “Roman Sexualities” by Judith P. Hallett and Marilyn B. Skinner, “Sexuality and Gender in the Classical World” by Laura McClure, and “Recruitment and Training of Gladiators” by Rodger Dunkle. In the first part of my letter, I mention the shame and infamia that Cassia has brought upon her family by making the choice to become a female gladiator: “I know you both fund it disgusting and unthinkable that I gave up my status as the daughter of a wealthy senator to pursue the lifestyle of a female gladiator”. I drew a lot of my information for this section from Anna McCollough’s article “Female Gladiators in Imperial Rome: Literary Context and Historical Fact”. -

Journey to Antioch, However, I Would Never Have Believed Such a Thing

Email me with your comments! Table of Contents (Click on the Title) Prologue The Gentile Heart iv Part I The Road North 1 Chapter One The Galilean Fort 2 Chapter Two On the Trail 14 Chapter Three The First Camp 27 Chapter Four Romans Versus Auxilia 37 Chapter Five The Imperial Way Station 48 Chapter Six Around the Campfire 54 Chapter Seven The Lucid Dream 63 Chapter Eight The Reluctant Hero 68 Chapter Nine The Falling Sickness 74 Chapter Ten Stopover In Tyre 82 Part II Dangerous Passage 97 Chapter Eleven Sudden Detour 98 Chapter Twelve Desert Attack 101 Chapter Thirteen The First Oasis 111 Chapter Fourteen The Men in Black 116 Chapter Fifteen The Second Oasis 121 Chapter Sixteen The Men in White 128 Chapter Seventeen Voice in the Desert 132 Chapter Eighteen Dark Domain 136 Chapter Nineteen One Last Battle 145 Chapter Twenty Bandits’ Booty 149 i Chapter Twenty-One Journey to Ecbatana 155 Chapter Twenty-Two The Nomad Mind 162 Chapter Twenty-Three The Slave Auction 165 Part III A New Beginning 180 Chapter Twenty-Four A Vision of Home 181 Chapter Twenty-Five Journey to Tarsus 189 Chapter Twenty-Six Young Saul 195 Chapter Twenty-Seven Fallen from Grace 210 Chapter Twenty-Eight The Roman Escorts 219 Chapter Twenty-Nine The Imperial Fort 229 Chapter Thirty Aurelian 238 Chapter Thirty-One Farewell to Antioch 246 Part IV The Road Home 250 Chapter Thirty-Two Reminiscence 251 Chapter Thirty-Three The Coastal Route 259 Chapter Thirty-Four Return to Nazareth 271 Chapter Thirty-Five Back to Normal 290 Chapter Thirty-Six Tabitha 294 Chapter Thirty-Seven Samuel’s Homecoming Feast 298 Chapter Thirty-Eight The Return of Uriah 306 Chapter Thirty-Nine The Bosom of Abraham 312 Chapter Forty The Call 318 Chapter Forty-One Another Adventure 323 Chapter Forty-Two Who is Jesus? 330 ii Prologue The Gentile Heart When Jesus commissioned me to learn the heart of the Gentiles, he was making the best of a bad situation.