The Vera Historia Behind Lucian's Relationship with Homer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

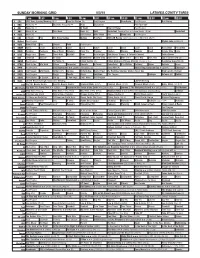

Sunday Morning Grid 5/3/15 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 5/3/15 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program NewsRadio Paid Program Bull Riding 4 NBC News (N) Å Meet the Press (N) Å News Equestrian PGA Tour Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Hour Of Power Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Å This Week News (N) NBA Basketball Brooklyn Nets at Atlanta Hawks. (N) Å Basketball 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX In Touch Paid Fox News Sunday Midday Pre-Race NASCAR Racing Sprint Cup Series: GEICO 500. (N) Å 13 MyNet Paid Program Afghan Luke (2011) (R) 18 KSCI Breast Red Paid Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Cosas Local Jesucristo Local Local Gebel Local Local Local Local RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Dewberry Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexico Cooking Fresh Simply Ming Lidia 28 KCET Raggs Fast. Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News Asia Insight Rick Steves’ Europe: A Cultural Carnival Father Brown 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Bucket-Dino Bucket-Dino Doki (TVY7) Doki (TVY7) Dive, Olly Dive, Olly Taxi › (2004) (PG-13) 34 KMEX Paid Program Al Punto (N) Fútbol Central (N) Fútbol Mexicano Primera División: Pumas vs Azul República Deportiva (N) 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Carpenter Liberate In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written Pathway Super Kelinda Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Program 101 Dalmatians ›› (1996) Glenn Close. -

Pleasure and Instruction in the Prologue of Longus

SYMBOLAE PHILOLOGORUM POSNANIENSIUM GRAECAE ET LATINAE XIX• 2009 pp. 95-114. ISBN 978-83-232-2153-1. ISSN 0302-7384 ADAM MICKIEWICZUNIVERSITYPRESS, POZNAŃ BRUCE DUNCAN MACQUEEN Department of Comparative Literature, University of Silesia pl. Sejmu Śląskiego 1, 40-032 Katowice Poland PLEASURE AND INSTRUCTION IN THE PROLOGUE OF LONGUS’ DAPHNIS AND CHLOE ABSTRACT . Bruce Duncan MacQueen, Pleasure and instruction in the Prologue of Longus’ “Daphnis and Chloe”. The present study attempts to demonstrate that the ancient Greek novel Daphnis and Chloe system- atically explores the problem expressed by Horace in the phrase docere et delectare, and that this purpose is announced in the Prologue. The functions of prologues as such are briefly reviewed. After a consideration of the prologues of the remaining ancient Greek novels, the Prologue of Longus’s Daphnis and Chloe is analyzed line by line. Longus uses the Prologue, then, to establish a series of dialectical tensions that operate throughout the novel, allowing it to delight and instruct at the same time. Key words: ancient Greek novel, Eros, paradox, paideia, hunting. INTRODUCTION A paradox often repeated, like a metaphor, eventually loses the shock value that makes it useful as a figure of speech. To use the terminology of cognitive psychology, it comes to be “overlearned,” repeated without reflec- tion at particular moments when the requisite prompt occurs. Its very fa- miliarity makes it fade into the background, where it ceases to draw atten- tion to itself. We have been told since childhood, for example, to “turn the other cheek,” so we repeat the phrase automatically and almost entirely ignore it in practice, since it no longer demands our attention. -

Reviving the Pagan Greek Novel in a Christian World Burton, Joan B Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1998; 39, 2; Proquest Pg

Reviving the Pagan Greek novel in a Christian World Burton, Joan B Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Summer 1998; 39, 2; ProQuest pg. 179 Reviving the Pagan Greek Novel in a Christian World Joan B. Burton N THE CHRISTIAN WORLD of Constantinople, in the twelfth century A.D., there was a revival of the ancient Greek novel, I replete with pagan gods and pagan themes. The aim of this paper is to draw attention to the crucial role of Christian themes such as the eucharist and the resurrection in the shaping and recreation of the ancient pagan Greek world in the Byzan tine Greek novels. Traditionally scholars have focused on similarities to the ancient Greek novels in basic plot elements, narrative tech niques, and the like. This has often resulted in a general dismissal of the twelfth-century Greek novels as imitative and unoriginal.1 Yet a revision of this judgment has begun to take place.2 Scholars have noted that there are themes and imagery in these novels that would sound contemporary to many of their Byzantine readers, for example, ceremonial throne scenes and 1 Thus B. E. Perry, The Ancient Romances: A Literary-Historical Account of Their Origins (Berkeley 1967) 103: "the slavish imitations of Achilles Tatius and Heliodorus which were written in the twelfth century by such miserable pedants as Eustathius Macrembolites, Theodorus Prodromus, and Nicetas Eugenianus, trying to write romance in what they thought was the ancient manner. Of these no account need be taken." 2See R. Beaton's important book, The Medieval Greek Romance 2 (London 1996) 52-88, 210-214; M. -

The Death of Heraclitus Fairweather, Janet Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Fall 1973; 14, 3; Proquest Pg

The Death of Heraclitus Fairweather, Janet Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies; Fall 1973; 14, 3; ProQuest pg. 233 The Death of Heraclitus Janet Fairweather ECENTLY there has been a revival of interest in a theory, Roriginally put forward by A. Gladisch,l about one ancient ac count of the death of Heraclitus. According to Neanthes of Cyzicus 2 Heraclitus, suffering from dropsy, attempted to cure him self by covering his body with manure and lying out in the sun to dry, but he was made unrecognizable by the dung covering and was finally eaten by dogs. Gladisch and others have seen in this anecdote a veiled allusion to a certain Zoroastrian ritual, described in the Videvdat (8.37f), in which a man who has come into contact with a corpse which has not been devoured by scavengers is supposed to rid himself of the polluting demon, Nasu the Druj, by lying on the ground, covering himself with bull's urine, and having some dogs brought to the scene. The fact that we find both in Neanthes' tale and in this ritual the use of bovine excreta, exposure of a man's body in the sun, and the inter vention of dogs has seemed to some scholars too remarkable to be coincidental. Gladisch and, following him, F. M. Cleve3 have seen in Neanthes' anecdote an indication that Heraclitus might have ordered a Zoroastrian funeral for himself. M. L. West,4 more cautiously and subtly, has suggested that the story of the manure treatment and the dogs could have originated as an inference from some allusion Hera clitus may have made to the purification ritual in a part of his work now lost, perhaps in connection with his sneer (fr.86 Marcovich=B 5 D/K) at people who attempt to rid themselves of blood pollution by spilling more blood. -

Getting Acquainted with the Myths Search the GML Advanced

Document belonging to the Greek Mythology Link, a web site created by Carlos Parada, author of Genealogical Guide to Greek Mythology Characters • Places • Topics • Images • Bibliography • PDF Editions About • Copyright © 1997 Carlos Parada and Maicar Förlag. Getting acquainted with the myths Search the GML advanced Sections in this Page I. Getting acquainted with the myths II. Four "gateways" of mythology III. A strategy for reading the myths I. Getting acquainted with the myths What "getting acquainted" may mean We'll first try to clarify the meaning that the expression "getting acquainted" may have in this context: In a practical sense, I mean by "acquaintance" a general knowledge of the tales of mythology, including how they relate to each other. This concept includes neither analysis nor interpretation of the myths nor plunging too deep into one tale or another. In another sense, the expression "getting acquainted" has further implications that deserve elucidation: First of all, let us remember that we naturally investigate what we ignore, and not what we already know; accordingly, we set out to study the myths not because we feel we know them but because we feel we know nothing or very little about them. I mention this obvious circumstance because I believe that we should bear in mind that, in this respect, we are not in the same position as our remote ancestors, who may be assumed to have made their acquaintance with the myths more or less in the same way one learns one's mother tongue, and consequently did not have to study them in any way. -

Homer's Iliad Via the Movie Troy (2004)

23 November 2017 Homer’s Iliad via the Movie Troy (2004) PROFESSOR EDITH HALL One of the most successful movies of 2004 was Troy, directed by Wolfgang Petersen and starring Brad Pitt as Achilles. Troy made more than $497 million worldwide and was the 8th- highest-grossing film of 2004. The rolling credits proudly claim that the movie is inspired by the ancient Greek Homeric epic, the Iliad. This was, for classical scholars, an exciting claim. There have been blockbuster movies telling the story of Troy before, notably the 1956 glamorous blockbuster Helen of Troy starring Rossana Podestà, and a television two-episode miniseries which came out in 2003, directed by John Kent Harrison. But there has never been a feature film announcing such a close relationship to the Iliad, the greatest classical heroic action epic. The movie eagerly anticipated by those of us who teach Homer for a living because Petersen is a respected director. He has made some serious and important films. These range from Die Konsequenz (The Consequence), a radical story of homosexual love (1977), to In the Line of Fire (1993) and Air Force One (1997), political thrillers starring Clint Eastwood and Harrison Ford respectively. The Perfect Storm (2000) showed that cataclysmic natural disaster and special effects spectacle were also part of Petersen’s repertoire. His most celebrated film has probably been Das Boot (The Boat) of 1981, the story of the crew of a German U- boat during the Battle of the Atlantic in 1941. The finely judged and politically impartial portrayal of ordinary men, caught up in the terror and tedium of war, suggested that Petersen, if anyone, might be able to do some justice to the Homeric depiction of the Trojan War in the Iliad. -

Starting with Anacreon While Preparing a Compendium of Essays on Sappho and Her Ancient Reception

Starting with Anacreon while preparing a compendium of essays on Sappho and her ancient reception The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Nagy, Gregory. 2021.02.06. "Starting with Anacreon while preparing a compendium of essays on Sappho and her ancient reception." Classical Inquiries. http://nrs.harvard.edu/ urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries. Published Version https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/starting-with-anacreon- while-preparing-a-compendium-of-essays-on-sappho-and-her- ancient-reception/ Citable link https://nrs.harvard.edu/URN-3:HUL.INSTREPOS:37367198 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Classical Inquiries Editors: Angelia Hanhardt and Keith Stone Consultant for Images: Jill Curry Robbins Online Consultant: Noel Spencer About Classical Inquiries (CI ) is an online, rapid-publication project of Harvard’s Center for Hellenic Studies, devoted to sharing some of the latest thinking on the ancient world with researchers and the general public. While articles archived in DASH represent the original Classical Inquiries posts, CI is intended to be an evolving project, providing a platform for public dialogue between authors and readers. Please visit http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.eresource:Classical_Inquiries for the latest version of this article, which may include corrections, updates, or comments and author responses. Additionally, many of the studies published in CI will be incorporated into future CHS pub- lications. -

The Birds and Plato's Symposium.Pdf

Baquerizo 1 Olivia M. Baquerizo ([email protected]) CAMWS 2021, Plato Panel Fordham Univeristy Friday, April 9 Aetiologies of Eros: The Birds and Plato’s Symposium abstract: https://camws.org/sites/default/files/meeting2021/abstracts/2389AetiologiesofEros.pdf Ephialtes and Otus in the Platonic Aristophanes’ Speech 1. Ephialtes and Otus in the Symposium (190b.5-190c) trans. Nehamas and Woodruff ἦν οὖν τὴν ἰσχὺν δεινὰ καὶ τὴν ῥώμην, καὶ τὰ In strength and power, therefore, they were φρονήματα μεγάλα εἶχον, ἐπεχείρησαν δὲ τοῖς θεοῖς, terrible, and they had great ambitions. They καὶ ὃ λέγει Ὅμηρος περὶ Ἐφιάλτου τε καὶ Ὤτου, περὶ made an attempt on the gods, and homer’s ἐκείνων λέγεται, τὸ εἰς τὸν οὐρανὸν ἀνάβασιν story about Ephiatles and Otus was ἐπιχειρεῖν ποιεῖν, ὡς ἐπιθησομένων τοῖς θεοῖς originally about them: how they tried to make an ascent to heaven so as to attack the gods. 2. Ephialtes and Otus in the Odyssey (11.306-20) trans. A. S. kline τὴν δὲ μετ᾽ Ἰφιμέδειαν, Ἀλωῆος παράκοιτιν Next I saw Iphimedeia, Aloeus’ wife, who εἴσιδον, ἣ δὴ φάσκε Ποσειδάωνι μιγῆναι, claimed she had slept with Poseidon. She καί ῥ᾽ ἔτεκεν δύο παῖδε, μινυνθαδίω δ᾽ ἐγενέσθην, too bore twins, short-lived, godlike Otus and Ὦτόν τ᾽ ἀντίθεον τηλεκλειτόν τ᾽ Ἐφιάλτην, famous Ephialtes, the tallest most handsome οὓς δὴ μηκίστους θρέψε ζείδωρος ἄρουρα men by far, bar great Orion, whom the καὶ πολὺ καλλίστους μετά γε κλυτὸν Ὠρίωνα: 310 fertile Earth ever nourished. They were ἐννέωροι γὰρ τοί γε καὶ ἐννεαπήχεες ἦσαν fifteen feet wide, and fifty feet high at nine εὖρος, ἀτὰρ μῆκός γε γενέσθην ἐννεόργυιοι. -

The History of Sexuality, Volume 2: the Use of Pleasure

The Use of Pleasure Volume 2 of The History of Sexuality Michel Foucault Translated from the French by Robert Hurley Vintage Books . A Division of Random House, Inc. New York The Use of Pleasure Books by Michel Foucault Madness and Civilization: A History oflnsanity in the Age of Reason The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences The Archaeology of Knowledge (and The Discourse on Language) The Birth of the Clinic: An Archaeology of Medical Perception I, Pierre Riviere, having slaughtered my mother, my sister, and my brother. ... A Case of Parricide in the Nineteenth Century Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison The History of Sexuality, Volumes I, 2, and 3 Herculine Barbin, Being the Recently Discovered Memoirs of a Nineteenth Century French Hermaphrodite Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings, 1972-1977 VINTAGE BOOKS EDlTlON, MARCH 1990 Translation copyright © 1985 by Random House, Inc. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto. Originally published in France as L' Usage des piaisirs by Editions Gallimard. Copyright © 1984 by Editions Gallimard. First American edition published by Pantheon Books, a division of Random House, Inc., in October 1985. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Foucault, Michel. The history of sexuality. Translation of Histoire de la sexualite. Includes bibliographical references and indexes. Contents: v. I. An introduction-v. 2. The use of pleasure. I. Sex customs-History-Collected works. -

Oscar Wilde's Aesthetics in the Making: the Reviews of the Grosvenor

Oscar Wilde’s Aesthetics in the Making: The Reviews of the Grosvenor Gallery exhibitions of 1877 and 1879 Anne-Florence Gillard-Estrada To cite this version: Anne-Florence Gillard-Estrada. Oscar Wilde’s Aesthetics in the Making: The Reviews of the Grosvenor Gallery exhibitions of 1877 and 1879. Etudes Anglaises, Klincksieck, 2016, 69, pp.36-48. hal-02092904 HAL Id: hal-02092904 https://hal-normandie-univ.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02092904 Submitted on 8 Apr 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Anne-Florence GILLARD-ESTRADA Oscar Wilde’s Aesthetics in the Making: The Reviews of the Grosvenor Gallery exhibitions of 1877 and 1879) This paper explores the first two texts Wilde published in 1877 and 1879 in Irish periodicals, which are reviews of the first and third exhibitions of the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877 and 1879. Wilde commented on the developments that had been affecting British painting for the past fifteen years or so. He addressed the works of artists who were then associated with the “classic” school of painting as well as with “Aestheticism”—which often overlapped. Moreover, he engaged in a dialogue with the reviewers and art critics who were favourable to such art. -

Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology

The Ruins of Paradise: Studies in Early Mediterranean Poetics and Cosmology by Matthew M. Newman A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Classical Studies) in the University of Michigan 2015 Doctoral Committee: Professor Richard Janko, Chair Professor Sara L. Ahbel-Rappe Professor Gary M. Beckman Associate Professor Benjamin W. Fortson Professor Ruth S. Scodel Bind us in time, O Seasons clear, and awe. O minstrel galleons of Carib fire, Bequeath us to no earthly shore until Is answered in the vortex of our grave The seal’s wide spindrift gaze toward paradise. (from Hart Crane’s Voyages, II) For Mom and Dad ii Acknowledgments I fear that what follows this preface will appear quite like one of the disorderly monsters it investigates. But should you find anything in this work compelling on account of its being lucid, know that I am not responsible. Not long ago, you see, I was brought up on charges of obscurantisme, although the only “terroristic” aspects of it were self- directed—“Vous avez mal compris; vous êtes idiot.”1 But I’ve been rehabilitated, or perhaps, like Aphrodite in Iliad 5 (if you buy my reading), habilitated for the first time, to the joys of clearer prose. My committee is responsible for this, especially my chair Richard Janko and he who first intervened, Benjamin Fortson. I thank them. If something in here should appear refined, again this is likely owing to the good taste of my committee. And if something should appear peculiarly sensitive, empathic even, then it was the humanity of my committee that enabled, or at least amplified, this, too.