Celebrating the Seasonal Holy-Days

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

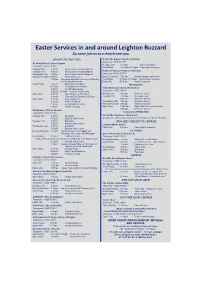

Easter Services in and Around Leighton Buzzard

Easter Services in and around Leighton Buzzard Do come join us at a church near you CHURCH OF ENGLAND St John the Baptist Church, Stanbridge Telephone: 01525 210828 All Saints Church, Church Square Tuesday 11th 8.00 pm Holy Communion Telephone: 01525 381418 Good Friday 12.00 pm to 3.00pm Church open for prayer Monday 10th 8.00 pm Holy Communion with Address Tuesday 11th 8.00 pm Holy Communion with Address St Giles of Provence Church, Totternhoe Wednesday 12th 8.00 pm Holy Communion with Address Telephone: 01582 662778 Maundy Thursday 10.00 am Holy Communion Maundy Thursday 7.00 pm Maundy Supper and Service 7.30 pm Sung Eucharist with Ceremony of Washing Good Friday 12.00 pm to 3.00pm Church open for prayer of Feet followed by Vigil Easter Day 10.00 am Holy Communion Good Friday 12 noon Reflections and Music METHODIST 12.45 pm Preaching of the Passion Trinity Methodist Church, North Street 2.00 pm Good Friday Liturgy 3.00 pm to 5.00pm Church remains open Telephone: 01525 371905 Easter Eve 9.00 am Quiet Service of Reflection Monday 10th 8.00 pm Reflective Service 9.00 pm Vigil and First Eucharist of Easter Tuesday 11th 10.00 am Morning Service Easter Day 8.00 am Holy Communion 8.00 pm Reflective Service 9.15 am Easter Eucharist Wednesday 12th 8.00 pm Reflective Service 11.15 am Messy Mass for Easter Maundy Thursday 8.00 pm Holy Communion 6.00 pm Festal Evensong Easter Day 10.30 am Easter Day Communion Service 6.00 pm Reflective Service St Barnabas’ Church, Linslade Telephone: 01525 372149 SOCIETY OF FRIENDS Monday 10th 9.30 am Eucharist -

List of Religious Holidays Permitting Student Absence from School

Adoption Resolution May 5, 2021 RESOLUTION The List of Religious Holidays Permitting Student Absence from School WHEREAS, according to N.J.S.A. 18A:36-14 through 16 and N.J.A.C. 6A:32-8.3(j), regarding student absence from school because of religious holidays, the Commissioner of Education, with the approval of the State Board of Education, is charged with the responsibility of prescribing such rules and regulations as may be necessary to carry out the purpose of the law; and WHEREAS, the law provides that: 1. Any student absent from school because of a religious holiday may not be deprived of any award or of eligibility or opportunity to compete for any award because of such absence; 2. Students who miss a test or examination because of absence on a religious holiday must be given the right to take an alternate test or examination; 3. To be entitled to the privileges set forth above, the student must present a written excuse signed by a parent or person standing in place of a parent; 4. Any absence because of a religious holiday must be recorded in the school register or in any group or class attendance record as an excused absence; 5. Such absence must not be recorded on any transcript or application or employment form or on any similar form; and 6. The Commissioner, with the approval of the State Board of Education, is required to: (a) prescribe such rules and regulations as may be necessary to carry out the purposes of this act; and (b) prepare a list of religious holidays on which it shall be mandatory to excuse a student. -

![110// Here Followeth the Feast of St. Peter Ad Vincula, at Lammas [August 1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7035/110-here-followeth-the-feast-of-st-peter-ad-vincula-at-lammas-august-1-1157035.webp)

110// Here Followeth the Feast of St. Peter Ad Vincula, at Lammas [August 1]

The Golden Legend or Lives Of The Saints Compiled by Jacobus de Voragine, Archbishop of Genoa, 1275 Englished by William Caxton, First Edition 1483 From the Temple Classics Edited by F.S. Ellis 110// HERE FOLLOWETH THE FEAST OF ST. PETER AD VINCULA, AT LAMMAS [AUGUST 1] The feast of St. Peter the apostle that is called ad Vincula was established for four causes. That is to wit, in remembrance of the deliverance of St. Peter, and in mind of deliverance of Alexander, for to destroy the customs of the paynims [pagans], and for to get absolution of spiritual bonds. THE DELIVERANCE OF ST. PETER nd the first cause which is in remembrance of St. Peter. For as it is said in the History AScholastic that Herod Agrippa went to Rome, and was right familiar with Gaius, nephew of Tiberius emperor. And on a day as Herod was in a chariot brought with Gaius, he lifted up his hands unto heaven and said: I would gladly see the death of this old fellow Peter, and the Lord of all the world. And the chariot man heard this word said of Herod, and anon told it to Tiberius. Wherefore Tiberius set Herod in prison. And as he was there he beheld on a day by him a tree, and saw upon the branches of this tree an owl which sat thereon, and another prisoner which was with him, that understood well divinations. said to him: Thou shalt be anon delivered, and shalt be enhanced to be a king, in such wise that thy friends shall have envy at thee, and thou die in that prosperity. -

Religious/Holy Days 2020-2021

Religious/Holy Days 2020-2021 Some days may require absence from school or fasting or other specific observance. All absences will be reviewed on an individual case-by-case basis in accordance with Plano ISD Board of Trustees’ Policies FEA, FEB, FNA, FNAB and state and federal laws and regulations. If questions arise, it is suggested that the campus administration work with Central Administration regarding such absences. Also note that some holidays may vary slightly based on local custom, group preference or moon sightings. This information is updated annually and an effort is made to be inclusive though the list is not exhaustive and any omissions of particular holidays is not intentional. BAHA’I HOLIDAYS July 9, 2020 *Martyrdom of the Bab October 20, 2020 *Birth of the Báb November 12, 2020 *Birth of Baha’u’llah November 26, 2020 *Day of the Covenant March 21, 2021 *Naw-Rúz (New Year) April 16, 2021 *First Day of Ridvan April 24, 2021 *Ninth Day of Ridvan May 2, 2021 *Last Day of Ridvan May 23, 2021 *Declaration of the Bab May 29, 2021 *Ascension of Baha’u’llah BUDDHIST OBSERVANCES December 8, 2020 **Bodhi Day (Rohatsu) February 8, 2021 Nirvana Day March 28, 2021 **Magha Puja Day May 19, 2021 **Visakha Puja - Buddha Day CHRISTIAN HOLIDAYS August 15, 2020 Assumption of Blessed Virgin Mary November 1, 2020 All Saints Day December 8, 2020 Immaculate Conception of Mary December 16-25, 2020 Posadas Navidenas December 25, 2020 *Christmas January 1, 2021 Mary, Mother of God January 6, 2021 Epiphany February 17, 2021 Ash Wednesday – Lent begins March 28, 2021 Palm Sunday April 2, 2021 Good Friday April 4, 2021 Easter May 13, 2021 Ascension of Jesus May 23, 2021 Pentecost NOTES: BOLD titles are primary holy days of a tradition. -

Have a Blessed Easter

Weekly Newsletter for St Martin’s Anglican Church Campbelltown Easter Sunday, 4 April 2021 Living God, we thank you for your vision for the whole 7 creation and that you call us When you enter any of our PLEASE REGISTER to share in your mission. church buildings, remember… We pray that you grow your church; REMINDER: DAYLIGHT SAVING ENDS EASTER SUNDAY MORNING Bring more people to – PUT YOUR CLOCKS BACK 1 HOUR BEFORE GOING TO BED SATURDAY NIGHT! faith in Jesus; Deepen our trust in you and knowledge of you; Help us to serve and bless our community; And strengthen us to be generous with the money and resources you give us. May we grow as disciples of Jesus and make disciples of others for the blessing of the world you love. In Jesus’ name we pray. Amen. I pray this every day; please join me and let’s put it into action. Rev’d Canon Mara Diocesan Have a Blessed Easter Vision Statement 2022 Changes to Parish Email Addresses “We will be a Following on from last week’s advice that the email addresses for Diocese of St Martin’s Office and The Message had been suspended temporarily, the flourishing Anglican new addresses are as follows: communities, united St Martin’s Office [email protected] and connected, whose The Message [email protected] members are This information will appear on the back page of The Message each week. confident and competent to live as St Martin’s mission is to do God’s work and message through disciples of Jesus Worship - Spiritual formation - Christ in the power of the Holy Spirit.” Service to others & Building Community. -

Pentecost 2020 Newsletter

1 Pentecost 2020 Greetings Brothers and Sisters of St. David’s Bean Blossom. So much has changed since I last wrote an article for the newsletter I hardly know where to begin. This pandemic is something I never would have predicted or expected to happen. It has been a time of change and adaptation to say the least. It has been hard to not see you all in the flesh. I’ve always said that pastoral care has to be done in person and that is just not possible in this time. You all have been very quick to learn this new technology. I thank all the younger members who were able to help me get started especially Lauren, Ed, Cori, Ben and Adie. I thank Yvonne for writing the grant for new tech equipment which we will definitely be needing. I thank you all for continuing to be the church even in this time of great uncertainty. Your will- ingness to continue to participate and to make important decisions and share your ideas and care for one another has allowed me to keep seeing the love of God in our midst. It was very hard to not open the Farmer’s Market this year but I feel that we can continue to serve the needs of the food insecure in new ways. We are going to start meeting to figure out a plan for gradual re-opening. There is a committee devoted solely to this purpose. To be honest I don’t think this pandemic will be something that goes away quickly. -

HALLOWEEN, an ASTRONOMICAL HOLIDAY Halloween – Short for All Hallows’ Eve – Is an Astronomical Holiday

HALLOWEEN, AN ASTRONOMICAL HOLIDAY Halloween – short for All Hallows’ Eve – is an astronomical holiday. Sure, it’s the modern-day descendant from Samhain, a sacred festival of the ancient Celts and Druids in the British Isles. But it’s also a cross-quarter day, which is probably why Samhain occurred when it did. Early people were keen observers of the sky. A cross-quarter day is a day more or less midway between an equinox (when the sun sets due west) and a solstice (when the sun sets at its most northern or southern point on the horizon). Halloween – October 31 – is approximately at the midway point between the autumn equinox and winter solstice in the Northern Hemisphere. In other words, there are eight major seasonal subdivisions of every year. They include the Equinoxes, solstices and cross-quarter days are all hallmarks March and September equinoxes, the June and of Earth's orbit around the sun. Halloween is the fourth December solstices, and the intervening four cross-quarter day of the year. cross-quarter days. In modern times, the four cross-quarter days are often called Groundhog Day (February 2), May Day (May 1), Lammas (August 1) and Halloween (October 31). Halloween is the spookiest of the cross quarter days, possibly because it comes at a time of year when the days are growing shorter. On Halloween, it’s said that the spirits of the dead wander from sunset until midnight. After midnight – on November 1, which we now call All Saints’ Day – the ghosts are said to go back to rest. -

Religious Holidays

10 22 Religious Waqf al Arafa/Hajj Day | Ganesh Chaturthi | Hindu Muslim Festival honoring the god of (until 8/11) prosperity, prudence, and success Holidays Observance during Hajj, the Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca, when pilgrims pray for forgiveness and 29 mercy Beheading of St. John the Baptist | Christian Provided by Krishna Janmashtani | Hindu Remembrance of the death of Commemoration of the birth of John the Baptist The President's Krishna Committee on September 15 Religious, Assumption of the Blessed 1 Virgin Mary | Catholic Christian Religious year begins | Spiritual and Commemorating the assumption of Orthodox Christian Mary, mother of Jesus, into Start of the religious calendar year Nonreligious heaven Diversity Dormition of the Virgin Mary | 2 Orthodox Christian Obon/Ulambana | Buddhist, Observance of the death, burial, Shinto and transfer to heaven of the Also known as Ancestor Day, a Virgin Mary time to relieve the suffering of ghosts by making offerings to deceased ancestors 2020 16 Paryushana Parva | Jain Chinese Ghost Festival | August Festival signifying human Taoist, Buddhist emergence into a new world of Celebration in which the deceased spiritual and moral refinement, and are believed to visit the living 1 a celebration of the natural Lammas | Wiccan/Pagan qualities of the soul Celebration of the early harvest 8 Nativity of the Blessed Virgin 17 Fast in Honor of Holy Mother Mary | Orthodox Christian Marcus Garvey’s Birthday | of Jesus | Orthodox Christian Celebration of the birth of Mary, Beginning of the 14-day period -

Texas Local Council Covenant of the Goddess Wiccan Holy Days

Texas Local Council Covenant of the Goddess Wiccan Holy Days ~ also known as Sabbats In the days before the advent of electric lights and artificial time, our ancestors marked the turning of the seasons through their observation of the natural world. The awesome spectacle repeated in the pattern of the changing seasons still touches our lives. In the ages when people worked more closely with nature just to survive, the numinous power of this pattern had supreme recognition. Rituals and festivals evolved to channel these transformations for the good of the community toward a good sowing and harvest and bountiful herds and hunting. One result of this process is our image of the "Wheel of the Year" with its eight spokes -- the four major agricultural and pastoral festivals and the four minor solar festivals of the solstices and equinoxes. DECEMBER 19 - 21* -- WINTER SOLSTICE -- YULE The sun is at its nadir, the year's longest night. We internalize and synthesize the outward-directed activities of the previous summer months. Some covens hold a Festival of Light to commemorate the Goddess as Mother giving birth to the Sun God. Others celebrate the victory of the Lord of Light over the Lord of Darkness as the turning point from which the days will lengthen. The name "Yule" derives from the Norse word for "wheel", and many of our customs (like those of the Christian holiday) derive from Norse and Celtic Pagan practices (the Yule log, the tree, the custom of Wassailing, etc..) FEBRUARY 2 -- IMBOLC (OIMELC) OR BRIGID As the days' lengthening becomes perceptible, many candles are lit to hasten the warming of the earth and emphasize the reviving of life. -

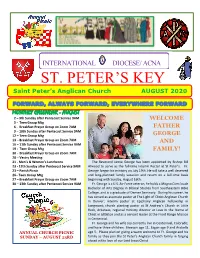

August Newsletter 2020

INTERNATIONAL DIOCESE/ ACNA ST. PETER’S KEY Saint Peter’s Anglican Church AUGUST 2020 Serving Our Lord in Fort Collins, Loveland, Windsor and Greeley - Colorado MONTHLY CALENDAR - AUGUST 2 – 9th Sunday after Pentecost Service 9AM WELCOME 5 - Teen Group Mtg 6 - Breakfast Prayer Group on Zoom 7AM FATHER 9 – 10th Sunday after Pentecost Service 9AM 12 – Teen Group Mtg GEORGE 13 – Breakfast Prayer Group on Zoom 7AM AND 16 – 11th Sunday after Pentecost Service 9AM 19 - Teen Group Mtg FAMILY! 20 - Breakfast Prayer Group on Zoom 7AM 20 – Vestry Meeting 21 - Men’s & Women’s Luncheons The Reverend Jamie George has been appointed by Bishop Bill 23 - 12th Sunday after Pentecost Service 9AM Atwood to serve as the full-time Interim Rector at St Peter’s. Fr. 23 – Parish Picnic George began his ministry on July 19th. He will take a well deserved 26– Teen Group Mtg and long-planned family vacation and return on a full-time basis 27 – Breakfast Prayer Group on Zoom 7AM beginning with Sunday, August 16th. 30 – 13th Sunday after Pentecost Service 9AM Fr. George is a U.S. Air Force veteran, he holds a Magna Cum Laude Bachelor of Arts Degree in Biblical Studies from Southeastern Bible College, and is a graduate of Denver Seminary. During his career, he has served as associate pastor at The Light of Christ Anglican Church in Denver; interim pastor at Epiphany Anglican Fellowship in Longmont; church planting pastor at St Andrew’s Church in Little Rock, Arkansas; regional ministry director at Love In the Name of Christ in Littleton and as a servant leader at the Front Range Mission in Centennial. -

RELIGIOUS OBSERVANCE CALENDAR July 2018 - June 2019

RELIGIOUS OBSERVANCE CALENDAR July 2018 - June 2019 NOTE 1. * Holy days usually begin at sundown the day before this date. 2. ** Local or regional customs may use a variation of this date. See the Interfaith Calendar Home Page (http://www.interfaith-calendar.org) for information or definitions. JULY 2018 9 Martyrdom of the Bab * - Baha'i 11 St. Benedict Day – Catholic Christian 13-15 Obon (Ulambana) ** - Buddhist - Shinto 15 St. Vladimir the Great Day – Orthodox Christian 22 Tish'a B'av * - Jewish 24 Pioneer Day - Mormon Christian 25 St. James the Great Day - Christian 27 Asalha Puja Day ** - Buddhist AUGUST 2018 1 Lammas - Christian Fast in Honor of Holy Mother of Jesus – Orthodox Christian 2 Lughnassad – Imbolc * - Wicca/Pagan (Northern & Southern Hemispheres) 6 Transfiguration of the Lord - Orthodox Christian 15 Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary - Catholic Christian Dormition of the Theotokos - Orthodox Christian 22-25 Eid al Adha * - Islam 29 Beheading of St. John the Baptist – Christian Raksha Bandhan ** - Hindu SEPTEMBER 2018 1 Religious year begins - Orthodox Christian 3 Krishna Janmashtami ** - Hindu 8 Nativity of Virgin Mary – Christian <SEPTEMBER 2018 cont’d> 10-11 Rosh Hashanah * - Jewish 12 New Year-Hijra * - Islam 13 Ganesh Chaturthi ** - Hindu 14 Elevation of the Life Giving Cross (Holy Cross) – Christian Paryushana Parva ** - Jain 19 Yom Kippur * - Jewish 21 Ashura * - Islam 22 Equinox Mabon - Ostara * - Wicca/Pagan (Northern & Southern hemispheres) 24-30 Sukkot * - Jewish 27 Meskel - Ethiopian Orthodox Christian 29 Michael and All Angels – Christian OCTOBER 2018 1 Shemini Atzeret * - Jewish 2 Simchat Torah * - Jewish 4 Saint Francis Day – Catholic Christian Blessing of the Animals – Christian 8 Thanksgiving – Canada – Interfaith 9-16 Navaratri ** - Hindu 18 St. -

83773 Diversity Calendar 17.Indd

A Partial Listing of Religious, Ethnic and Civic Observances 2017 New Year’s Day (U.S., International) January 1 Japanese New Year January 1 Shogatsu (Shinto New Year) January 1-3 Dia de los Santos Reyes/Th ree Kings Day (Latin America) January 6 Epiphany (Christian) January 6 *Asarah B’Tevet (Jewish) January 8 Makar Sankranti (Hindu) January 14 Birthday of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. (U.S.) January 16 Chinese New Year January 28 ______________________________________________________________ Imbolc/Imbolg (Pagan, Wiccan) February 2 *Tu B’Shevat (Jewish) February 11 National Foundation Day (Shinto) February 11 Presidents’ Day (U.S.) February 20 International Mother Language Day (International) February 21 Maha Shivaratri (Hindu) February 24 Clean Monday/Lent begins (Orthodox Christian) February 27 ______________________________________________________________ Ash Wednesday/Lent begins (Christian) March 1 Hinamatsuri (Japan) March 3 Ta’anit Esther (Jewish) March 9 *Purim (Jewish) March 12 Holi (Hindu) March 13 *Shushan Purim (Jewish) March 13 St. Patrick’s Day (Christian) March 17 Nowruz (Iranian New Year) March 20 *Rosh Chodesh Nisan (Jewish) March 28 ______________________________________________________________ Mahavir Jayanti (Jainism) April 8 Palm Sunday (Orthodox Christian) April 9 Palm Sunday (Christian) April 9 *Passover/Pesach (Jewish) April 11-18 Great Friday (Orthodox Christian) April 14 Good Friday (Christian) April 14 Holy Saturday (Orthodox Christian) April 15 Easter (Christian) April 16 Great and Holy Pascha (Orthodox Christian)