Ethnoecology of Oxalis Adenophylla Gillies Ex Hook. Ampamp

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

+1. Introduction 2. Cyrillic Letter Rumanian Yn

MAIN.HTM 10/13/2006 06:42 PM +1. INTRODUCTION These are comments to "Additional Cyrillic Characters In Unicode: A Preliminary Proposal". I'm examining each section of that document, as well as adding some extra notes (marked "+" in titles). Below I use standard Russian Cyrillic characters; please be sure that you have appropriate fonts installed. If everything is OK, the following two lines must look similarly (encoding CP-1251): (sample Cyrillic letters) АабВЕеЗКкМНОопРрСсТуХхЧЬ (Latin letters and digits) Aa6BEe3KkMHOonPpCcTyXx4b 2. CYRILLIC LETTER RUMANIAN YN In the late Cyrillic semi-uncial Rumanian/Moldavian editions, the shape of YN was very similar to inverted PSI, see the following sample from the Ноул Тестамент (New Testament) of 1818, Neamt/Нямец, folio 542 v.: file:///Users/everson/Documents/Eudora%20Folder/Attachments%20Folder/Addons/MAIN.HTM Page 1 of 28 MAIN.HTM 10/13/2006 06:42 PM Here you can see YN and PSI in both upper- and lowercase forms. Note that the upper part of YN is not a sharp arrowhead, but something horizontally cut even with kind of serif (in the uppercase form). Thus, the shape of the letter in modern-style fonts (like Times or Arial) may look somewhat similar to Cyrillic "Л"/"л" with the central vertical stem looking like in lowercase "ф" drawn from the middle of upper horizontal line downwards, with regular serif at the bottom (horizontal, not slanted): Compare also with the proposed shape of PSI (Section 36). 3. CYRILLIC LETTER IOTIFIED A file:///Users/everson/Documents/Eudora%20Folder/Attachments%20Folder/Addons/MAIN.HTM Page 2 of 28 MAIN.HTM 10/13/2006 06:42 PM I support the idea that "IA" must be separated from "Я". -

Spread of Citrus Tristeza Virus in a Heavily Infested Citrus Area in Spain

Spread of Citrus Tristeza Virus in a Heavily Infested Citrus Area in Spain P. Moreno, J. Piquer, J. A. Pina, J. Juarez and M. Cambra ABSTRACT. Spread of Citrus Tristeza Virus (CTV) in a heavily infested citrus area in Southern Valencia (Spain) has been monitored since 1981. Two adjacent plots with 400 trees each were selected and tested yearly by ELISA (enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay). One of them was planted to 4-yr-old Newhall navel orange on Troyer citrange and the other to 8-yr-old Marsh seedless grapefruit on the same rootstock. Both had been established using virus-free budwood. In 1981, 98.7% of the Newhall navel plants indexed CTV-positive and by 1984 all of them were infected, whereas only 17.8% of the Marsh grapefruit indexed CTV-positive in 1981, and 42.5% were infected in 1986. This is an indication that grapefruit is less susceptible than navel orange to tristeza infection under the Spanish field conditions. Wild plants of 66 species collected in the same heavily tristeza-infested area were also tested by ELISA to find a possible alternate non-citrus host. CTV was not found in any of the more than 450 plants analyzed. Index words. virus spread, ELISA, noncitrus hosts. Tristeza was first detected in virus diffusion under various environ- Spain in 1957 and since then has mental conditions. In this paper we caused the death of about 10 million present data on CTV spread in a trees grafted on sour orange and the heavily infested area. A survey progressive decline of an additional among wild plants growing in the several thousand hectares of citrus on same citrus area was also undertaken this rootstock. -

Old Cyrillic in Unicode*

Old Cyrillic in Unicode* Ivan A Derzhanski Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences [email protected] The current version of the Unicode Standard acknowledges the existence of a pre- modern version of the Cyrillic script, but its support thereof is limited to assigning code points to several obsolete letters. Meanwhile mediæval Cyrillic manuscripts and some early printed books feature a plethora of letter shapes, ligatures, diacritic and punctuation marks that want proper representation. (In addition, contemporary editions of mediæval texts employ a variety of annotation signs.) As generally with scripts that predate printing, an obvious problem is the abundance of functional, chronological, regional and decorative variant shapes, the precise details of whose distribution are often unknown. The present contents of the block will need to be interpreted with Old Cyrillic in mind, and decisions to be made as to which remaining characters should be implemented via Unicode’s mechanism of variation selection, as ligatures in the typeface, or as code points in the Private space or the standard Cyrillic block. I discuss the initial stage of this work. The Unicode Standard (Unicode 4.0.1) makes a controversial statement: The historical form of the Cyrillic alphabet is treated as a font style variation of modern Cyrillic because the historical forms are relatively close to the modern appearance, and because some of them are still in modern use in languages other than Russian (for example, U+0406 “I” CYRILLIC CAPITAL LETTER I is used in modern Ukrainian and Byelorussian). Some of the letters in this range were used in modern typefaces in Russian and Bulgarian. -

Mother's Day Weekend

MAY 2019 Serving You Since 1955 981 Alden Lane, Livermore, CA • www.aldenlane.com • (925) 447-0280 Mother’s Day Weekend May 11th & 12th Take time to Smell the Roses! To celebrate Mother’s Day, Kelly will set up a “FRESH Cut Perfume Bar” where roses will be displayed and labeled. You’ll be able to cup the blooms and inhale their fragrance. What a great way to experience the wonder of rose diversity. Come sip iced tea and “Take Time to Smell the Roses”! Our “Rose Garden” is awash with color. The roses are blooming beautifully and it’s a wonderful time to select just the right color, form and FRAGRANCE for your garden and vase. Stroll the aisles and soak up the beauty and perfume. We had the opportunity to visit a rose hybridizer where specialized staff discerningly evaluate each rose variety bloom and translate its aromas, much like a vintner describing a wine. Take your turn at sampling the essence of each rose. Is it citrus, notes of old rose or a hint of Hyacinth? This will be a fun and ‘Fragrant’ activity. Heather will have a “Floral” Market set up in the “Rose Garden” filled with blossom themed gift items including soaps & lotions. Don’t miss Nancy’s rose companion Pop Up Garden demonstrating what plants to pair with your roses. Her artful combinations will inspire you! SAVE THE DATE!! Art Under the Oaks $$ It’s Time for $$ on July 20 & 21 from 11-4 p.m. The event showcases $$ Bonus Dollars Again! $$ many talented Our traditional springtime event – artists, musicians Bonus Dollars are back! and wine makers. -

Pharmacological and Therapeutic Potential of Oxalis Corniculata Linn. Ansari Mushir, Nasreen Jahan*, Nadeem Ashraf, Mohd

Anti-proliferative and proteasome inhibitory activity Discoveryof Murraya koenigii Phytomedicine … 2015; 2 ( 3 ) : 18 - 22 . doi: 10.15562/phytomedicine.2015.2 Bindu Noolu & 6 Ayesha Ismail www.phytomedicine.ejournals.ca MINI REVIEW Pharmacological and therapeutic potential of Oxalis corniculata Linn. Ansari Mushir, Nasreen Jahan*, Nadeem Ashraf, Mohd. Imran Khan ABSTRACT Oxalis corniculata is commonly known as Indian wood Sorrel. In Unani it is called as Hummaz and distributed in the whole northern temperate zone, United State of America, Arizona and throughout India. Oxalis corniculata is used in Unani medicine in the management of liver disorders, jaundice, skin diseases, urinary diseases etc. The plant been proven to possess various pharmacological activities like liver tonic, appetizer, diuretic, anthelmintic, emmenagogue, anti-inflammatory, analgesic, anti-pyretic, blood purifier etc. Here we summarize the therapeutic potential of Oxalis corniculata. Keywords: Hummaz, Unani medicine, Oxalis corniculata, Indian wood sorrel Introduction Therapeutic uses Oxalis corniculata Linn. is a well-known Bustani Hummaz (garden variety) is plant described in ancient text of Unani physician beneficial in the treatment of safrawi amraz by the name of Hummaz. It belongs to the family (bilious diseases). Gargling with decoction of its Oxalidaceae which comprises 8 genera and 900 leaves relieves marze akala (stomatitis), it has species being prevalent in the tropics and beneficial effect in treating bilious vomiting, and subtropics and having richest representation in palpitation. Its lotion is used as a wash for snake Southern Hemisphere. In India 2 genera and a bite, the decoction of leaves is used in treatment dozen of species have been reported. It has of Khanazir (cervical lymphadenitis) and paste of delicate-appearance, low growing and herbaceous leaves is used to treat skin diseases like Quba plant. -

Oxalis Violacea L. Violet Wood-Sorrel

New England Plant Conservation Program Oxalis violacea L. Violet Wood-Sorrel Conservation and Research Plan for New England Prepared by: Thomas Mione Professor Central Connecticut State University For: New England Wild Flower Society 180 Hemenway Road Framingham, MA 01701 508/877-7630 e-mail: [email protected] • website: www.newfs.org Approved, Regional Advisory Council, December 2002 1 SUMMARY Violet Wood-Sorrel (Oxalis violacea L., Oxalidaceae) is a low-growing herbaceous, self-incompatible perennial that produces violet flowers in May, June and again in September. Reproduction is both sexual (with pollination mostly by bees), and asexual (by way of runners). The species is widely distributed in the United States but is rare in New England. Oxalis violacea is an obligate outcrosser: the species is distylous, meaning that there are two flower morphs (pin and thrum), with a given plant producing one morph, not both. Pin flowers are more common than thrum flowers. In New England, the habitat varies from dry to moist, and for populations to remain vigorous forest canopies must remain partially open. Succession, the growth of plants leading to shading, is a factor contributing to decline of O. violacea in New England, as are invasive species and habitat fragmentation. Fire benefits this species, in part by removing competitors. Human consumption of the leaves has been reported. Oxalis violacea has a Global Status Rank of G5, indicating that it is demonstrably widespread, abundant and secure. In Massachusetts, it is ranked as Threatened; five occurrences are current (in four towns among three counties) and 10 are historic. In Connecticut, it is listed as a species of Special Concern; 10 occurrences are current (in ten towns among six counties) and 19 are historic. -

Fita and Fitb, a Neisseria Gonorrhoeae Protein Complex Involved in the Regulation Of

FitA and FitB, a Neisseria gonorrhoeae Protein Complex Involved in the Regulation of Transcellular Migration by John Scott.)Vilbur A DISSERTATION Presented to the Department of Molecular Microbiology and Immunology and the Oregon Health and Sciences University School of Medicine in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy March 2006 School of Medicine Oregon Health and Sciences University CERTIFICATE OF APPROVAL This is to certify that the Ph.D. Thesis of John Scott Wilbur has been approved Dr. Fred Heffron, Member TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of contents Acknowledgments iv Abstract v Chapter 1: Introduction 1 1.0 Neisseria 2 1.1 Clinical manifestation 2 1.2 The GC infection process 3 1.2.1 Loose adherence and microcolony formation 3 1.2.2 Tight adherence and invasion 4 1.2.3 Intracellular replication and transcytosis 5 1.3 The role of transcytosis in infection 6 1.4 Antigenic variation of GC virulence factors 7 1.4.1 PilE recombination with pilS locus 7 1.4.2 Opa phase variation 9 1.5 Tissue culture models of infection 10 1.6 Identification of the fit locus 10 1.7 FitA and ribbon-helix-helix DNA binding proteins 11 1.8 FitB and PIN domains 12 1.9 Present work 14 References 17 Chapter 1 Figure legends 29 Chapter 1 Figures 33 Chapter 2: Manuscript 1: Neisseria gonorrhoeae FitA interacts with FitB 36 to bind DNA through its ribbon-helix-helix motif Abstract 39 Introduction 40 Experimental procedures 42 Results 47 Discussion 54 References 55 Tables 1-3 59 Figure legend 62 Figures 1-6 64 Chapter 3: Manuscript -

Host Plants and Nectar Plants of Butterflies in San Diego County

Host Plants and Nectar Plants of Butterflies in San Diego County Speaker: Marcia Van Loy San Diego Master Gardener Association Butterfly Caterpillar Host Plant Butterfly Nectar Source Admiral Aspens, birches, oaks sp., willows, poplars, Aphid honeydew, bramble blossom (Rubus) honeysuckle, wild cherry Admiral, California Sister Coast & canyon live oak Rotting fruit, dung, sap; rarely flowers Admiral, Lorquin’s Willows, cottonwood, aspens, oak sp. Calif. lilac, mint, sap, fruit, dung poplars, willows sp. Admiral, Red Aspens, birches, hops, nettle sp., oak sp., Dandelion, goldenrod, mallow, verbena, willows buddleja, purple coneflower, garlic chives, lantana, marigold, privet, thistel, dogbane Blues: Achmon, Arrowhead, Alfalfa, clovers, dogwoods, legumes, lupines, California aster, asclepias, Spanish lotus, Bernardino, Lupine, Marine, vetches, wild cherry, Chinese wisteria, legumes, lupine, heliotrope, wild pea, dudleya, Sonoran plumbago violets, buckwheat (Eriogonum) Buckeye, Common Snapdragon, loosestrife (Lysimachia, Ajuga (carpet bugle) Lythurum), mallows, nettles, thistles, plantains, antennaria everlasting Cabbage White Mustard and cabbage family, broccoli, Arugula, blood flower, Brazilian verbena, nasturtium spp. buddleja, asclepias, day lily, lantana, lavender, liatris, marigold, mint, oregano, radishes, red clover, some salvia and sedum, thyme, tithonia, winter cress, zinnia, eupatorium Checkerspots: Wright’s, Gabb’s, Asters, chelone, digitalis, hostas, rudbeckia Asclepias, viburnum, wild rose, Calif. aster Imperial, Variable, Chalcedon, -

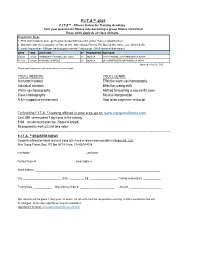

Fita Registration Form

F.I.T.A™ 2021 F.I.T.A™ - Fitness Instructor Training Academy Turn your passion for fitness into becoming a group fitness instructor! These skills apply to all class formats. Registration Steps 1. Print and complete form, go to www.citysportsfitness.com under "Career Opportunities". 2. Mail form with check payable to Fitness Intl., Attn: Group Fitness, PO Box 54104, Irvine, CA, 92619-4104 3. Early Registration: $99 per training post marked 7 days prior. ($169 General Admission) DATE TIME LOCATION ST PRESENTER ADDRESS 5/22/21 12-6pm FREEMONT - FARWELL DR. (CSC) CA MONICA 39153 FARWELL DR FREMONT CA 94538 7/17/21 12-6pm HAYWARD WHIPPLE CA MONICA 2401 WHIPPLE RD HAYWARD CA 94544 Updated 3/11/2021 CSC *Dates and locations are subject to change or cancellation YOU’LL RECEIVE: YOU’LL LEARN: Instructor handout Effective warm-up choreography Individual attention Effective cueing skills Warm-up choreography Method to teaching a successful class Class choreography Musical interpretation A fun supportive environment How to be a dynamic instructor To find the F.I.T.A. ® training offered in your area, go to: www.citysportsfitness.com Cost: $99 - postmarked 7 days prior to the training. $169 – on site registration fee. (Space is limited) Be prepared to work out and take notes. •••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• F.I.T.A. ® REGISTER NOW! Complete information below and mail along with check or money order payable to Fitness Intl., LLC, Attn: Group Fitness -

Seize the Ъ: Linguistic and Social Change in Russian Orthographic Reform Eugenia Sokolskaya

Seize the Ъ: Linguistic and Social Change in Russian Orthographic Reform Eugenia Sokolskaya It would be convenient for linguists and language students if the written form of any language were a neutral and direct representation of the sounds emitted during speech. Instead, writing systems tend to lag behind linguistic change, retaining old spellings or morphological features instead of faithfully representing a language's phonetics. For better or worse, sometimes the writing can even cause a feedback loop, causing speakers to hypercorrect in imitation of an archaic spelling. The written and spoken forms of a language exist in a complex and fluid relationship, influenced to a large extent by history, accident, misconception, and even politics.1 While in many language communities these two forms – if writing exists – are allowed to develop and influence each other in relative freedom, with some informal commentary, in some cases a willful political leader or group may step in to attempt to intentionally reform the writing system. Such reforms are a risky venture, liable to anger proponents of historic accuracy and adherence to tradition, as well as to render most if not all of the population temporarily illiterate. With such high stakes, it is no wonder that orthographic reforms are not often attempted in the course of a language's history. The Russian language has undergone two sharply defined orthographic reforms, formulated as official government policy. The first, which we will from here on call the Petrine reform, was initiated in 1710 by Peter the Great. It defined a print alphabet for secular use, distancing the writing from the Church with its South Slavic lithurgical language. -

^^^^^ Us R/Ns Night Thc Dug, Thou Can'tt Nat Then Be Jaue to Uny Man."

;' ' /. my : /> . ffffé^jggfjjmgmfià_;¡ÜBjWBSjBC? ffTM^^Ü." J. "2j|Í"^...J_L.ll^Jün.-1.1''?^"J Jit- >?«?»»-m»yii- i-ijrii r mmmi r J "tf'T-^ '»'?"?-' -ir-rr r ijilgr-, i- j-j II IJ .im ..j'UJi_ 1 L* '1 ."****g****B?i?"y " ' " ' ' 'f*'" """i»»'.-»*1""1*.>*I!!^W*!*****^^,*''* " Tn (nitic own self bc (ruc, and it mu ^ ^^^^^ us r/ns night thc dug, thou can'tt nat then be JaUe to uny man." M ROBT A, THOMPSON & CO. P1CKKNS COURT HOUSE, S, C, SEPTEMBER 21,1867. VOL, ll,.NO. 52. m.".. ni WM*.»^^IIM>.»W>IIII L^WIUIIHIUH-, - ? -^, ?"M>MM^_ tmmmmmtmimmmHmtmmmmmm*. SATUB|AY,.»i^iwiniM?»?.??? MIMHIW ???- city alone a PoMotu-aUo promises majority oí whoso iovo of liborty and Republicau th, ai of 75,000 votes. vania puuci« pirro mstj^.s poU'-cal slaves nuder <.ke nttaiudcf ov ex pott Judo \o.vt. Tho samo oxisls tn Clio Lotter Pouuuyl ami Indians pies i.> tho stvougc.it of their nala o ? lea.! O'.'a CR. majority of thc Southern fror.\ Hon. B- J?. Porry. seemed feeling )p;*W)lpîeJ ,?\:-bfggO. ill r-o.'iîi- hja substituted t.s eteotois will oxiyt Staten, P conlidontof giving lt would bo «Vi'.unii>g authority in nib . j SoymouvandBlair stränge, Indeed. W tho Noirboru o.:i a renegades who '-.vs ufog thsm o*.ly t>« iu placo oí' (lio moo. ot' or.»' own raoo tl us I h Tho GiiEEMVibLE, Sh C., July 27, 1803. h.aidsouio majority. Tito Statua oi' did not vive hi the o." tlr.'.r Jacobins íu Congi-.WJ havo got n, ^' Mnvy- people up i,iPjCj:y ?ool% O.Víi". -

![[ Plug + Play ] Programs](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/1136/plug-play-programs-1371136.webp)

[ Plug + Play ] Programs

plug + play [ VARIETY CATALOG 2011-2012 ] ® PLUG CONNECTION 2627 Ramona Drive Vista, California 92084 760.631.0992 760.940.1555 (fax) [email protected] plugconnection.com © 2011 PLUG CONNECTION. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. PLUG INTO THE MOST STIMULATING SOURCE FOR DAZZLING PLANTS. OUR TEAM IS INTERLINKED WITH THE MOST FORWARD-THINKING BREEDERS ON THE PLANET, ALLOWING US TO BRING YOU IMPRESSIVE NEW VARIETIES AND TURN UP THE VOLUME ON THE CLASSICS. EACH OF THESE POWERFUL PLANTS COMES PACKAGED WITH SIMPLICITY, SERVICE AND SUPPORT, MAKING IT EASY TO KEEP YOUR BUSINESS SHOOTING UPWARD. INSTALL OUR PRODUCTS AND GET PROFITS. PROSPERITY. PEACE OF MIND. IF YOU’RE READY FOR THE GOOD STUFF, IT’S TIME TO HIT PLAY. PLUG + PLAY PROGRAMS. 17 WESTFLOWERS® BY WESTHOFF. 78 ERYSIMUM GLOW™. 18 ASTERS KICKIN™ . 82 contents ERYSIMUM RYSI. 19 BIDENS. 84 of ERYSIMUM POEM . 20 BRACTEANTHA . 84 ERYSIMUM WINTER. 21 COSMOS CHOCAMOCHA. 84 table BUDDLEJA BUZZ™ BUTTERFLY BUSH. 22 CHRYSOCEPHALUM. 85 GERANIUM FIREWORKS® COLLECTION. 24 OSTEOSPERMUM . 85 GERANIUM – IVY P. PELTATUM HYBRIDS . 25 LUCKY LANTERN™ ABUTILON . 85 GERANIUM – CRISPUM ANGEL EYES® SERIES. 26 ORGANIKS®. 86 GERANIUM – GRANDIFLORA ARISTO® SERIES. 27 TOMACCIO™. 92 GERANIUM ZONAL . 28 SUPERNATURALS™ GRAFTED VEGETABLES . 94 ANGELONIA PAC ADESSA® SERIES. 30 BAMBOO FROM TISSUE CULTURE. 98 BEGONIA SUMMERWINGS™ . 32 KIA ORA FLORA. 101 BEGONIA BELLECONIA™ . 33 COPROSMA. 102 TROPICAL SURGE. 34 HEBE . 104 DRAKENSBERG™ DAISY HARDY GARDEN GERBERA. 36 CORDYLINE . 104 BELARINA™ DOUBLE-FLOWERED PRIMULA. 38 ITOH PEONY. 106 NESSIE™ PLUS NEMESIA. 40 TECOMA BELLS OF FIRE™ . 108 KAROO™ NEMESIA. 41 TECOMA LYDIA™. 109 DIASCIA MARSHMALLOW™ SERIES. 42 POWERFUL PROGRAMS. 111 ALLURE™ OXALIS TRIANGULARIS HYBRIDS.