Police in the Enquiry Into the Murder of a PRC National

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926

The Guangzhou-Hongkong Strike, 1925-1926 Hongkong Workers in an Anti-Imperialist Movement Robert JamesHorrocks Submitted in accordancewith the requirementsfor the degreeof PhD The University of Leeds Departmentof East Asian Studies October 1994 The candidateconfirms that the work submitted is his own and that appropriate credit has been given where referencehas been made to the work of others. 11 Abstract In this thesis, I study the Guangzhou-Hongkong strike of 1925-1926. My analysis differs from past studies' suggestions that the strike was a libertarian eruption of mass protest against British imperialism and the Hongkong Government, which, according to these studies, exploited and oppressed Chinese in Guangdong and Hongkong. I argue that a political party, the CCP, led, organised, and nurtured the strike. It centralised political power in its hands and tried to impose its revolutionary visions on those under its control. First, I describe how foreign trade enriched many people outside the state. I go on to describe how Chinese-run institutions governed Hongkong's increasingly settled non-elite Chinese population. I reject ideas that Hongkong's mixed-class unions exploited workers and suggest that revolutionaries failed to transform Hongkong society either before or during the strike. My thesis shows that the strike bureaucracy was an authoritarian power structure; the strike's unprecedented political demands reflected the CCP's revolutionary political platform, which was sometimes incompatible with the interests of Hongkong's unions. I suggestthat the revolutionary elite's goals were not identical to those of the unions it claimed to represent: Hongkong unions preserved their autonomy in the face of revolutionaries' attempts to control Hongkong workers. -

Snakeheadsnepal Pakistan − (Pisces,India Channidae) PACIFIC OCEAN a Biologicalmyanmar Synopsis Vietnam

Mongolia North Korea Afghan- China South Japan istan Korea Iran SnakeheadsNepal Pakistan − (Pisces,India Channidae) PACIFIC OCEAN A BiologicalMyanmar Synopsis Vietnam and Risk Assessment Philippines Thailand Malaysia INDIAN OCEAN Indonesia Indonesia U.S. Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1251 SNAKEHEADS (Pisces, Channidae)— A Biological Synopsis and Risk Assessment By Walter R. Courtenay, Jr., and James D. Williams U.S. Geological Survey Circular 1251 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR GALE A. NORTON, Secretary U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES G. GROAT, Director Use of trade, product, or firm names in this publication is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Geological Survey. Copyrighted material reprinted with permission. 2004 For additional information write to: Walter R. Courtenay, Jr. Florida Integrated Science Center U.S. Geological Survey 7920 N.W. 71st Street Gainesville, Florida 32653 For additional copies please contact: U.S. Geological Survey Branch of Information Services Box 25286 Denver, Colorado 80225-0286 Telephone: 1-888-ASK-USGS World Wide Web: http://www.usgs.gov Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Walter R. Courtenay, Jr., and James D. Williams Snakeheads (Pisces, Channidae)—A Biological Synopsis and Risk Assessment / by Walter R. Courtenay, Jr., and James D. Williams p. cm. — (U.S. Geological Survey circular ; 1251) Includes bibliographical references. ISBN.0-607-93720 (alk. paper) 1. Snakeheads — Pisces, Channidae— Invasive Species 2. Biological Synopsis and Risk Assessment. Title. II. Series. QL653.N8D64 2004 597.8’09768’89—dc22 CONTENTS Abstract . 1 Introduction . 2 Literature Review and Background Information . 4 Taxonomy and Synonymy . -

The Unknown History of New York City's Chinatown: a Story of Crime During the Years of American Prohibition Kathryn Christense

The Unknown History of New York City’s Chinatown: A Story of Crime During the Years of American Prohibition Kathryn Christensen: Undergraduate of History and Asian Studies at SUNY New Paltz Popular interpretations of immigrants in New York City during the era of Prohibition have looked at it through the lens of European immigrants. Groups such as the Italian Mafia, and Irish gangs in New York City are a well-rehearsed story within the history of Prohibition. However, Europeans were not the only immigrants that began to flood into the ports of New York City during the early 20th century. Within New York City’s Chinatown there was the emergence of a vast network of organized criminal activity, along with various raids revealing rice wine moonshine and other violations of the 18th amendment, just like their European counterparts. Though largely overlooked in the historiography, this paper argues that Chinatown,and the Chinese in New York City played an integral role in the Prohibition era United States. In order to understand the Chinese population that lived in the United States during the early 1900s, it is important to lay the framework for why they first came to the United States. Like many other immigrant groups that immigrated during this time, many Chinese came over to escape a difficult political and economic climate. In China, the Opium war left the Chinese defeated by the British Empire leaving its reputation as the protectorate and superpower of the East shattered. This was accompanied by famines and floods across the nation resulting in economic catastrophe which further resulted in civil war and several uprisings, most notably the Taiping Rebellion.1 The unstable environment in China caused several Chinese to flee the country. -

HONG KONG and SOUTH CHINA: a BRIEF CHRONOLOGY (From Various Sources)

HONG KONG AND SOUTH CHINA: A BRIEF CHRONOLOGY (from various sources) 214 BCE Guangzhou established in the Northern Pearl River delta and walled by Emperor Qin Shi Huang of the Qin dynasty (221-206 BCE). Area becomes a center for industry and trade. Nauyue kings of Western Han dynasty rule there (206 BCE-24 CE; tomb in Guangzhou). By Tang Dynasty (618-907 CCE): Guangzhou is international port, controlling almost all of China's spice trade amid activities of maritime coast. 12th –15th C. Southern Sung (1127-1280) and Yuan Dynasties (1280-1363) Hakka (guest) peoples move southward and settle in marginal areas. Guangzhou less accessible to Southern Sung capital than other centers in Fukien. 1368-1644 Ming Dynasty: consolidation of Chinese Rule. Guangzhou continues to develop, particularly known for silk, crafts and trade. Local intellectuals explore Cantonese culture. After 1431, however, China cuts off trade and contact with the world. 1513 Portuguese Jorge Alvares reaches mouth of the Pearl river on board a rented Burmese vessel and realizes he has located "Cathay" building upon a Portuguese route around Africa, India and Indonesia. In 1517 Tomas Pires, ambassador from Portugal, arrives with fleet in Canton. After waiting two years, meets the emperor in Nanjing, but treaties fail in Beijing when the Emperor Chang Te dies. After further misunderstandings on land and a sea battle with the fleet, relations deteriorate. Pires and his mission die in prison. 1540 Portuguese settle at Liampo on the Pearl River and begin lucrative trade with the Japanese, whom they find by accident in 1542. Liampo sacked by Chinese in 1549 and Portuguese retreat to the island of Sanchuang. -

Organised Crime Around the World

European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control, affiliated with the United Nations (HEUNI) P.O.Box 161, FIN-00131 Helsinki Finland Publication Series No. 31 ORGANISED CRIME AROUND THE WORLD Sabrina Adamoli Andrea Di Nicola Ernesto U. Savona and Paola Zoffi Helsinki 1998 Copiescanbepurchasedfrom: AcademicBookstore CriminalJusticePress P.O.Box128 P.O.Box249 FIN-00101 Helsinki Monsey,NewYork10952 Finland USA ISBN951-53-1746-0 ISSN 1237-4741 Pagelayout:DTPageOy,Helsinki,Finland PrintedbyTammer-PainoOy,Tampere,Finland,1998 Foreword The spread of organized crime around the world has stimulated considerable national and international action. Much of this action has emerged only over the last few years. The tools to be used in responding to the challenges posed by organized crime are still being tested. One of the difficulties in designing effective countermeasures has been a lack of information on what organized crime actually is, and on what measures have proven effective elsewhere. Furthermore, international dis- cussion is often hampered by the murkiness of the definition of organized crime; while some may be speaking about drug trafficking, others are talking about trafficking in migrants, and still others about racketeering or corrup- tion. This report describes recent trends in organized crime and in national and international countermeasures around the world. In doing so, it provides the necessary basis for a rational discussion of the many manifestations of organized crime, and of what action should be undertaken. The report is based on numerous studies, official reports and news reports. Given the broad topic and the rapidly changing nature of organized crime, the report does not seek to be exhaustive. -

TRIADS Peter Yam Tat-Wing *

116TH INTERNATIONAL TRAINING COURSE VISITING EXPERTS’ PAPERS TRIADS Peter Yam Tat-wing * I. INTRODUCTION This paper will draw heavily on the experience gained by law enforcement Triad societies are criminal bodies in the HKSAR in tackling the triad organisations and are unlawful under the problem. Emphasis will be placed on anti- Laws of Hong Kong. Triads have become a triad law and Police enforcement tactics. matter of concern not only in Hong Kong, Background knowledge on the structure, but also in other places where there is a beliefs and rituals practised by the triads sizable Chinese community. Triads are is important in order to gain an often described as organized secret understanding of the spread of triads and societies or Chinese Mafia, but these are how triads promote illegal activities by simplistic and inaccurate descriptions. resorting to triad myth. With this in mind Nowadays, triads can more accurately be the paper will examine the following issues: described as criminal gangs who resort to triad myth to promote illegal activities. • History and Development of Triads • Triad Hierarchy and Structure For more than one hundred years triad • Characteristics of Triads activities have been noted in the official law • Differences between Triads, Mafia and police reports of Hong Kong. We have and Yakuza a long history of special Ordinances and • Common Crimes Committed by related legislation to deal with the problem. Triads The first anti-triad legislation was enacted • Current Triad Situation in Hong in 1845. The Hong Kong Special Kong Administrative Region (HKSAR) has, by • Anti-triad Laws in Hong Kong far, the longest history, amongst other • Police Enforcement Strategy jurisdictions, in tackling the problem of • International Cooperation triads and is the only jurisdiction in the world where specific anti-triad law exists. -

Messianism and the Heaven and Earth Society: Approaches to Heaven and Earth Society Texts

Messianism and the Heaven and Earth Society: Approaches to Heaven and Earth Society Texts Barend J. ter Haar During the last decade or so, social historians in China and the United States seem to have reached a new consensus on the origins of the Heaven and Earth Society (Tiandihui; "society" is the usual translation for hui, which, strictly speaking, means "gathering"; for the sake of brevity, the phenomenon is referred to below with the common alternative name "Triad," a translation of sänke hui). They view the Triads äs voluntary brotherhoods organized for mutual support, which later developed into a successful predatory tradition. Supporters of this Interpretation react against an older view, based on a literal reading of the Triad foundation myth, according to which the Triads evolved from pro-Ming groups during the early Qing dynasty. The new Interpretation relies on an intimate knowledge of the official documents that were produced in the course of perse- cuting these brotherhoods on the mainland and on Taiwan since the late eigh- teenth Century. The focus of this recent research has been on specific events, resulting in a more detailed factual knowledge of the phenomenon than before (Cai 1987; Qin 1988: 1—86; Zhuang 1981 provides an excellent historiographical survey). Understandably, contemporary social historians have hesitated to tackle the large number of texts produced by the Triads because previous historians have misinterpreted them and because they are füll of obscure religious Information and mythological references. Nevertheless, the very fact that these texts were produced (or copied) continuously from the first years of the nineteenth Century —or earlier—until the late 1950s, and served äs the basis for Triad initiation rituals throughout this period, leaves little doubt that they were important to the members of these groups. -

Chinese Exclusion and Tong Wars in Portland, Oregon

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 12-2019 More Than Hatchetmen: Chinese Exclusion and Tong Wars in Portland, Oregon Brenda M. Horrocks Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Horrocks, Brenda M., "More Than Hatchetmen: Chinese Exclusion and Tong Wars in Portland, Oregon" (2019). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 7671. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/7671 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MORE THAN HATCHETMEN: CHINESE EXCLUSION AND TONG WARS IN PORTLAND, OREGON by Brenda M. Horrocks A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS in History Approved: ______________________ ____________________ Colleen O’Neill, Ph.D. Angela Diaz, Ph.D. Major Professor Committee Member ______________________ ____________________ Li Guo, Ph.D. Richard S. Inouye, Ph.D. Committee Member Vice Provost for Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2019 ii Copyright © Brenda Horrocks All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT More Than Hatchetmen: Chinese Exclusion and Tong Wars in Portland, Oregon by Brenda M. Horrocks, Master of Arts Utah State University, 2019 Major Professor: Dr. Colleen O’Neill Department: History During the middle to late nineteenth century, Chinese immigration hit record levels in the United States. This led to the growth of Chinatowns across the West Coast. -

Chinese Organized Crime in Latin America

Department of Justice Weapons and money seized by U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration Chinese Organized Crime in Latin America BY R. EVAN ELLis n June 2010, the sacking of Secretary of Justice Romeu Tuma Júnior for allegedly being an agent of the Chinese mafia rocked Brazilian politics.1 Three years earlier, in July 2007, the Ihead of the Colombian national police, General Oscar Naranjo, made the striking procla- mation that “the arrival of the Chinese and Russian mafias in Mexico and all of the countries in the Americas is more than just speculation.”2 Although, to date, the expansion of criminal ties between the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and Latin America has lagged behind the exponen- tial growth of trade and investment between the two regions, the incidents mentioned above high- light that criminal ties between the regions are becoming an increasingly problematic by-product of expanding China–Latin America interactions, with troubling implications for both regions. Although data to quantify the character and extent of such ties are lacking, public evidence suggests that criminal activity spanning the two regions is principally concentrated in four cur- rent domains and two potentially emerging areas. The four groupings of current criminal activ- ity between China and Latin America are extortion of Chinese communities in Latin America by groups with ties to China, trafficking in persons from China through Latin America into the United States or Canada, trafficking in narcotics and precursor chemicals, and trafficking in con- traband goods. The two emerging areas are arms trafficking and money laundering. It is important to note that this analysis neither implicates the Chinese government in such ties nor absolves it, although a consideration of incentives suggests that it is highly unlikely that the government would be involved in any systematic fashion. -

Trafficking for Forced Criminal Activities and Begging in Europe Exploratory Study and Good Practice Examples

Trafficking for Forced Criminal Activities and Begging in Europe Exploratory Study and Good Practice Examples September 2014 RACE in Europe Project Partners Trafficking for Forced Criminal Activities and Begging in Europe Exploratory Study and Good Practice Examples “With the financial support of the Prevention of and Fight against Crime Programme European Commission- Directorate-General Home Affairs” ISBN 978–0–900918–91–0 Acknowledgements and contributors This publication was made possible by the information and advice provided by the RACE in Europe project partners and a variety of individuals, agencies and organisations across Europe, who have shared their experience, and agreed to be interviewed or to take part in focus groups. Our thanks go to all RACE in Europe seminar participants who provided information through interviews, questionnaires and group discussions. Anti-Slavery would like to thank in particular Vicky Brotherton, Fiona Waters, Marie Jelinkova, Grainne O’Toole, Viginija Petruskaite, Chloe Setter, Klara Skrivankova, Bernie Gravett, Michal Krebs and Walter Hilhorst for researching, writing and contributing their expertise and information for this publication. RACE in Europe project partner profiles UK Anti-Slavery International: Anti-Slavery International is the oldest human rights organisation in the world. The NGO works at the local, regional and international level to eliminate all forms of slavery around the world. www.antislavery.org ECPAT UK: ECPAT’s activities involve research, campaigning and lobbying government to prevent child exploitation and protect children in tourism and child victims of trafficking. www.ecpat.org.uk Specialist Policing Consultancy: Specialist Policing Consultancy provides expertise in combatting organised crime at an international level. -

Characteristics of Chinese Human Smugglers: a Cross-National Study, Final Report

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Characteristics of Chinese Human Smugglers: A Cross-National Study, Final Report Author(s): Sheldon Zhang ; Ko-lin Chin Document No.: 200607 Date Received: 06/24/2003 Award Number: 99-IJ-CX-0028 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. THE CHARACTERISTICS OF CHINESE HUMAN SMUGGLERS ---A CROSS-NATIONAL STUDY to the United States Department of Justice Office of Justice Programs National Institute of Justice Grant # 1999-IJ-CX-0028 Principal Investigator: Dr. Sheldon Zhang San Diego State University Department of Sociology 5500 Campanile Drive San Diego, CA 92 182-4423 Tel: (619) 594-5449; Fax: (619) 594-1325 Email: [email protected] Co-Principal Investigator: Dr. Ko-lin Chin School of Criminal Justice Rutgers University Newark, NJ 07650 Tel: (973) 353-1488 (Office) FAX: (973) 353-5896 (Fa) Email: kochinfGl,andronieda.rutgers.edu- This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. -

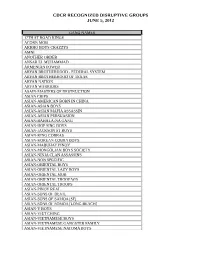

Cdcr Recognized Disruptive Groups June 5, 2012

CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 GANG NAMES 17TH ST ROAD KINGS ACORN MOB AKRHO BOYS CRAZZYS AMNI ANOTHER ORDER ANSAR EL MUHAMMAD ARMENIAN POWER ARYAN BROTHERHOOD - FEDERAL SYSTEM ARYAN BROTHERHOOD OF TEXAS ARYAN NATION ARYAN WARRIORS ASAIN-MASTERS OF DESTRUCTION ASIAN CRIPS ASIAN-AMERICAN BORN IN CHINA ASIAN-ASIAN BOYS ASIAN-ASIAN MAFIA ASSASSIN ASIAN-ASIAN PERSUASION ASIAN-BAHALA-NA GANG ASIAN-HOP SING BOYS ASIAN-JACKSON ST BOYS ASIAN-KING COBRAS ASIAN-KOREAN COBRA BOYS ASIAN-MABUHAY PINOY ASIAN-MONGOLIAN BOYS SOCIETY ASIAN-NINJA CLAN ASSASSINS ASIAN-NON SPECIFIC ASIAN-ORIENTAL BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL LAZY BOYS ASIAN-ORIENTAL MOB ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOP W/S ASIAN-ORIENTAL TROOPS ASIAN-PINOY REAL ASIAN-SONS OF DEVIL ASIAN-SONS OF SAMOA [SF] ASIAN-SONS OF SOMOA [LONG BEACH] ASIAN-V BOYS ASIAN-VIET CHING ASIAN-VIETNAMESE BOYS ASIAN-VIETNAMESE GANGSTER FAMILY ASIAN-VIETNAMESE NATOMA BOYS CDCR RECOGNIZED DISRUPTIVE GROUPS JUNE 5, 2012 ASIAN-WAH CHING ASIAN-WO HOP TO ATWOOD BABY BLUE WRECKING CREW BARBARIAN BROTHERHOOD BARHOPPERS M.C.C. BELL GARDENS WHITE BOYS BLACK DIAMONDS BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLE BLACK GANGSTER DISCIPLES NATION BLACK GANGSTERS BLACK INLAND EMPIRE MOB BLACK MENACE MAFIA BLACK P STONE RANGER BLACK PANTHERS BLACK-NON SPECIFIC BLOOD-21 MAIN BLOOD-916 BLOOD-ATHENS PARK BOYS BLOOD-B DOWN BOYS BLOOD-BISHOP 9/2 BLOOD-BISHOPS BLOOD-BLACK P-STONE BLOOD-BLOOD STONE VILLAIN BLOOD-BOULEVARD BOYS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER [LOT BOYS] BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-BELHAVEN BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-INCKERSON GARDENS BLOOD-BOUNTY HUNTER-NICKERSON