Light: the Return of the Sun a Two-Way Science Learning Unit For

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arctic Reading List

Arctic Reading List ESSENTIAL ¾ Lopez, Barry. Arctic Dreams. Vintage Books, 2001. ¾ McGhee, Robert. The Last Imaginary Place. University of Chicago Press, 2007. ¾ Pielou, E.C. A Naturalist’s Guide to the Arctic. University of Chicago Press, 1994. ¾ McGoogan, Ken. Dead Reckoning: the Untold Story of the Northwest Passage. Harper Collins, 2017. ¾ Watt-Cloutier, Sheila. The Right to Be Cold: One Woman’s Story of Protecting Her Culture, the Arctic, and the Whole Planet. Allen Lane, 2015. ¾ Alunik, Ishmael. Across Time and Tundra: the Inuvialuit of the Western Arctic. Vancouver, BC: Raincoast Books, 2003. ¾ Aupaluktuq, Nancy Pukirnak. The legend of Kiviuq as retold in the drawings of Nancy Pukirnak Aupaluktuq. Preface by Diane Webster. Ottawa, ON: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 2006. ¾ Barraclough, Eleanor Rosamund, Danielle Marine Cudmore, & Stefan Donecker eds. Imagining the Supernatural North. University of Alberta Press, 2016. ¾ Barrett, Andrea. The Voyage of the Narwhal. W.W. Norton and Company, 1999. ¾ Beauclerk Maurice, Edward. The Last Gentleman Adventurer. Mariner Books, 2006. ¾ Bennett, John and Susan Rowley, eds. Uqalurait: an Oral History of Nunavut. Montreal, QC: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2004. 473 pages. ¾ Berton, Pierre. The Arctic Grail: The Quest for the North West Passage and the North Pole. Anchor Canada, 2001. ¾ Bonesteel, Sarah. Canada's Relationship With Inuit: A History of Policy and Program Development. Prepared for Indian and Northern Affairs Canada; managed and edited by Erik Anderson ; prepared by Public History Inc. ; principal author: Sarah Bonesteel. Ottawa, ON: Indian and Northern Affairs Canada, 2008. ¾ Borkan, Bran & David Hirzel. When Your Life Depends on It: Extreme Decision-Making Lessons from the Antarctic. -

Celebrating 30 Years of Supporting Inuit Artists

Celebrating 30 Years of Supporting Inuit Artists Starting on June 3, 2017, the Inuit Art Foundation began its 30th Similarly, the IAF focused on providing critical health and anniversary celebrations by announcing a year-long calendar of safety training for artists. The Sananguaqatiit comic book series, as program launches, events and a special issue of the Inuit Art Quarterly well as many articles in the Inuit Artist Supplement to the IAQ focused that cement the Foundation’s renewed strategic priorities. Sometimes on ensuring artists were no longer unwittingly sacrificing their called Ikayuktit (Helpers) in Inuktut, everyone who has worked health for their careers. Though supporting carvers was a key focus here over the years has been unfailingly committed to helping Inuit of the IAF’s early programming, the scope of the IAF’s support artists expand their artistic practices, improve working conditions extended to women’s sewing groups, printmakers and many other for artists in the North and help increase their visibility around the disciplines. In 2000, the IAF organized two artist residencies globe. Though the Foundation’s approach to achieving these goals for Nunavik artists at Kinngait Studios in Kinnagit (Cape Dorset), NU, has changed over time, these central tenants have remained firm. while the IAF showcased Arctic fashions, film, performance and The IAF formed in the late 1980s in a period of critical transition other media at its first Qaggiq in 1995. in the Inuit art world. The market had not yet fully recovered from The Foundation’s focus shifted in the mid-2000s based on a the recession several years earlier and artists and distributors were large-scale survey of 100 artists from across Inuit Nunangat, coupled struggling. -

Gr.9 Nunavut-Final

GRADE 9 SOCIAL STUDIES & CIVICS NUNAVUT Part 1 The Land Claim Part 2 The Government GRADE 9 SOCIAL STUDIES & CIVICS NUNAVUT WRITTEN & EDITED BY NICK NEWBERY Publication of this unit was made possible by funding from the Qikiqtaaluk Corporation P.O.Box 1228, Iqaluit, Nunavut XOA OHO Copyright by Nick Newbery, Qikiqtaaluk Corporation & GN Dept. of Education Iqaluit, Nunavut XOA OHO All rights reserved Printed in Canada ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Arctic College Nunatta Campus: Unit on Nunavut Jim Bell: Nunatsiaq News Canadian Geographic Magazine Map of 3 National Parks Miro Cernetig: The Globe & Mail Department of Indian & Northern Affairs: Film: Changing the Map of Canada Gage Publishing: Indians, Inuit & Metis Government of Nunavut : Film: Nunavut Kanatami: Creation of a New Territory Hancock House Publishers: Eskimo Life Yesterday Inuit Broadcasting Corporation: Film: The Signing of the Nunavut Land Claim Agreement Gordon Mackay: GN Dept. of Sustainable Development Gavin Nesbitt Nunavut Implementation Commission Nunavut Tunngavik Inc. Map: Inuit Owned Lands Nunavut Land Claim Agreement Office of the Clerk of the Legislative Assembly Sutton Boys’ School: Inuit, Learning Through Action Whit Fraser Productions Teacher Reference This ready-to-photocopy unit attempts to outline the theme of Nunavut for Grade 9 ESL students in two parts: (i) The Land Claim and (ii) The Government. It can be seen as self-contained or as a starter kit for teachers wishing to go further. The project tries to provide opportunities for reading, writing, research & discussion coupled with regular review exercises. Some suggestions: 1. Comprehension: -teacher to read passage twice, explain text -do exercises orally then written -same procedure next day, students reading -assign as homework -test next day 2. -

Spring 2018 Spring Spring 2018 About Us Contents Spring 2018

Spring 2018 Fall 2017 Fall Fall 2017 Spring 2018 About Us Contents Spring 2018 About Us Ordering/Contact Information 4 Recent Awards 5 nhabit Media Inc. is an Inuit-owned publishing company Spring 2018 New Releases 6 Ithat aims to promote and preserve the stories, knowledge, Backlist Titles 22 and talent of northern Canada. Our mandate is to promote research in Inuit mythology Inhabit Community Imprint 46 and the traditional Inuit knowledge of Nunavummiut Periodicals 47 (residents of Nunavut). Our authors, storytellers, and artists Notes 48 bring this knowledge to life in a way that is accessible to readers in both northern and southern Canada. As the first independent publishing company in Nunavut, we are excited to bring Arctic stories and wisdom to the world. This project was made possible in part by the Government of Canada. We acknowledge the support of the Canada Council for the Arts for our publishing program. 2 | Spring 2018 Spring 2018 | 3 Spring 2018 Ordering | Contact Information Recent Awards Spring 2018 Ordering Information Recent Award Recognition for Inhabit Media Publications The Owl and the Lemming by Roselynn Akulukjuk 2018 Blue Spruce Award, Finalist Inhabit Media Inc. publications are distributed by Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited: 2017 Shining Willow Award, Finalist Fitzhenry & Whiteside Limited Those Who Run in the Sky by Aviaq Johnston 2017 Governor General’s Literary Award for Young People’s Literature - Text, Finalist 195 Allstate Parkway 2017 Burt Award for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Literature, Finalist Markham, -

1 President's Message

PRESIDENT’S MESSAGE by David M. Cvet Summer is upon us with a vengeance, breaking temperature records from the 1930's – at least in Toronto. The warmer weather has had some fits and starts, with warm weather followed by frost, causing newly planted peppers and tomatoes to be damaged beyond saving. However, these exciting events pale in comparison to seeing the Queen's Beasts (some depicted on the right) who will be attending the Society's formal dinner at this year's Annual General Meeting, scheduled for October 1-3, 2010 in Ottawa. The Annual Meeting itself will be held at the Delta Ottawa Hotel on Queen Street. The Saturday evening dinner will take place at the Canadian Museum of Civilization (across the Ottawa River in Gatineau, Quebec), which will provide a grand setting for our annual banquet, graced as it will be with these impressive “guests”. We are indeed grateful to David Rumball for organizing this event, and for arranging with the museum to have the Queen's Beasts available for the dinner. I encourage our members to make the necessary calendar and travel to enhance the “coolness” factor of the Society in order to attract arrangements to attend this splendid event. new members – and to retain our present ones. One important reason for having the AGM in Ottawa this year As an example, at the recent Toronto Branch AGM (combined (rather than being hosted by the Prairie Branch, as it would have with the Society's Board meeting earlier the same day) the been in the usual sequence) is the expectation that the new formal dinner at Hart House was visually recorded by a Canadian Heraldic Authority tabard (donated by the Society) photographer I had arranged as my guest. -

Flags and Banners

Flags and Banners A Wikipedia Compilation by Michael A. Linton Contents 1 Flag 1 1.1 History ................................................. 2 1.2 National flags ............................................. 4 1.2.1 Civil flags ........................................... 8 1.2.2 War flags ........................................... 8 1.2.3 International flags ....................................... 8 1.3 At sea ................................................. 8 1.4 Shapes and designs .......................................... 9 1.4.1 Vertical flags ......................................... 12 1.5 Religious flags ............................................. 13 1.6 Linguistic flags ............................................. 13 1.7 In sports ................................................ 16 1.8 Diplomatic flags ............................................ 18 1.9 In politics ............................................... 18 1.10 Vehicle flags .............................................. 18 1.11 Swimming flags ............................................ 19 1.12 Railway flags .............................................. 20 1.13 Flagpoles ............................................... 21 1.13.1 Record heights ........................................ 21 1.13.2 Design ............................................. 21 1.14 Hoisting the flag ............................................ 21 1.15 Flags and communication ....................................... 21 1.16 Flapping ................................................ 23 1.17 See also ............................................... -

Hemisphere Volume 9 Number 3, Winter 2001

Hemisphere Volume 9 Article 1 Issue 3 Winter 2001 Hemisphere Volume 9 Number 3, Winter 2001 Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/lacc_hemisphere Part of the Latin American Studies Commons Recommended Citation (2001) "Hemisphere Volume 9 Number 3, Winter 2001," Hemisphere: Vol. 9 : Iss. 3 , Article 1. Available at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/lacc_hemisphere/vol9/iss3/1 This work is brought to you for free and open access by the Kimberly Green Latin American and Carribbean Center (LACC) Publications Network at FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hemisphere by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Hemisphere Volume 9 Number 3, Winter 2001 This issue is available in Hemisphere: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/lacc_hemisphere/vol9/iss3/1 A MAGAZINE OF THE AMERICAS Volume 9 • Number 3 Winter 2001 http://lacc.fiu.edu Canada’s Nunavut Territory Defining Race in Brazil. inican Republic Education and Indigenous Identity in Mexico issue; Democracy and Civic Participation The Vote in Mexico Local Government in Latin America Photographs by Indigenous Children The Works of Maryse Conde INDAMI Presents... The 4th Annual Latin American and Caribbean Summer Dance Institute The next Summer Dance Institute is scheduled for June 25- July 1, 2001 and will feature Grupo Cultural Uk’ux Pop Wuj of Chichicastenango, Guatemala. Formed in 1991 with the mission of rescuing and fostering Mayan cultural traditions through a blend of dance and music, the company’s signature work, the Creation of Man, is based on the sacred book of the Maya Quiche, the Pop (time) Wuj (book). -

Kiviuq's Journey: Traditional Story Study

TRADITIONAL STORY STUDY KIVIUQ’S JOURNEY Design and layout copyright © 2018 Department of Education, Government of Nunavut Text copyright © 2018 Department of Education, Government of Nunavut Illustrations by Germaine Arnaktauyok copyright © 2014 Inhabit Media Inc. Developed and designed by Inhabit Education | www.inhabiteducation.com All rights reserved. The use of any part of this publication reproduced, transmitted by any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, or stored in a retrievable system, without written consent of the publisher, is an infringement of copyright law. Inuktut Titiqqiriniq This resource is part of Inuktut Titiqqiriniq, a comprehensive Inuktut literacy program that was created in Nunavut. Inuktut Titiqqiriniq was developed by Nunavut educators, linguists, and language consultants, with constant testing and input by Nunavut classroom teachers. Inuktut Titiqqiriniq provides instructional tools and resources to help students develop strong Inuktut language skills. Inuktut Titiqqiriniq takes a holistic and balanced approach to language learning. Inuktut Titiqqiriniq considers all aspects of and opportunities for literacy development. KIVIUQ’S JOURNEY Traditional Story Study Table of Contents General Accommodations and Modifications .........................................1 About This Traditional Story Study .................................................. 2 Icon Descriptions ................................................................... 3 Introductory Lesson ................................................................4 -

God Blood.Pdf

God Blood Who are we? True History of Civilization By William Johnson Copyright © 2011 William Johnson All rights reserved. ISBN: None yet Acknowledgements If not for Google, Wikipedia and Ancestry.com this would not be possible. Same goes for the Internet, Microsoft and Bill Gates and its power to give a writer the power to find more knowledge . A writer could have spent a life time researching the information that was available at the tip of my finger. DEDICATION This Book is dedicated to Mankind. May you be Enlightened. Table of Contents Chapter 1 The Beginning – A brief history My first Encounter – Christmas Eve 2009 The Trigger – Forgotten Knowledge of the Sumerians that piqued my curiosity. Curiosity killed the cat – The more information I found the more curious I got. Know our origins- Mesopotamia and the Sumerians connection to rise of civilization The Sumerians and the truth about Noah’s flood – It’s much older than the bible, by almost two thousand years, maybe more. Chapter 2 The Black Sea region –5000 - 5500BC, the Black Sea region and the earliest metals made. Indo Europeans Language – It was the base for civilization… Racial Traits –– Irish Red hair paired with light eyes unique history I bet you didn’t know but should. My second Encounter – One of the most profound, documented and proven God-like visitations in history. You read, you decide. -Who am I? – I start to question my sanity. Is this happening or am I crazy? An Angel Uriel Answers. My other spiritual encounters – These are other encounters that happened in a series of events that led up to an ultimate judgment. -

February 25, 2021

Literacy This Week February 18, 2021 Literacy Dates Indigenous Languages Month- February Black History Month- February Freedom to Read Week- February 21-27 In this issue Our Blog Announcements and Events Funding News, Research, Opinion Spotlight on Community Literacy Programs Resources and Websites Blog Huvi or Suvi? Guest blog written by Inuksuk McKay I grew up in Yellowknife, Northwest Territories, before Nunavut had become its own again. Although many Inuit lived, and still live, in Yellowknife, most of my family live in the Kitikmeot and Kivalliq regions. I grew up hearing Inuinnaqtun and Inuktitut dialects all the way from the western to central to eastern arctic. Among the many dialectal differences, one of the main ones is whether you use an ‘h’ sound or ‘s’ sound in certain words. For example, “huvi” or “suvi” for “what?” Read more Announcements and Events 2020 NWT Ministerial Literacy Awards The Government of the Northwest Territories, the Premiers of Canada Council of the Federation, and the NWT Literacy Council are pleased to announce the 2020 literacy awards, including eight Ministerial Literacy Awards and the Premiers of Canada Council of the Federation Literacy Award for the NWT. With this video, we celebrate the winners of the NWT Ministerial Literacy Awards and acknowledge their contributions to literacy in the NWT. Congratulations to all award recipients. Oral health story book available to communities NWTLC has partnered with Department of Health and Social Services to create a beautiful oral health story book written by Richard Van Camp and illustrated by Neiva Mateus. Would you like to help families in your community receive a copy of Our Ever Awesome NWT Brushing Song along with oral health supplies and activities? Please email [email protected] to discuss. -

Disk Pdf Version.Qxd

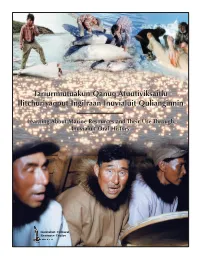

Tariurmiutuakun Qanuq Atuutiviksaitlu Ilitchuriyaqput Ingilraan Inuvialuit Qulianginnin Learning About Marine Resources and Their Use Through Inuvialuit Oral History Inuvialuit Cultural Resource Centre Tariurmiutuakun Qanuq Atuutiviksaitlu Ilitchuriyaqput Ingilraan Inuvialuit Qulianginnin Learning About Marine Resources and Their Use Through Inuvialuit Oral History Wesley Ovayuak stands on the tail of a beluga whale while eating maktak, ca. 1960s, Tuktoyaktuk. (Department of Information/NWT Archives/G-1979-023-1194) Report prepared for the Beaufort Sea Integrated Management Planning Initiative (BSIMPI) Working Group Funding provided by Fisheries and Oceans Canada and the Inuvialuit Cultural Resource Centre By Elisa J. Hart and Beverly Amos, Inuvialuit Cultural Resource Centre With guidance from Billy Day, Andy Tardiff, Frank Pokiak, and Max Kotokak, members of the Traditional Knowledge Sub-Group of the Beaufort Sea Integrated Management Planning Initiative Working Group. © Inuvialuit Cultural Resource Centre, 2004 ISUMAGIYAVUT Ukuanik makpiraaliurapta isumagiyavut tamaita COPEkutigun Akuqtuyualuit (Catholic) minisitaitkutigunlu nipiliurmata quliaqlutik ingilraanik qulianik. Ilagilugitlu savaktuat COPEmi, apiqsuqtuatlu, inugiaktuatlu mumiktisiyuat savaqasiqtuatlu. Quyanainniirikputlu Katliit minisitait katitchivakpangmata qulianik Inuvialungnin inuusimiktigun. Quyagiyavut innaaluit inugiaktuat nipiliurmata ukiungani 1950mingaaniin qitiqqanun aglaan 1970it, ilisarvigiyavut savaaptingnun. Quyanainni! DEDICATION This report is dedicated to -

Chapter 2 Incandescent Light Bulb

Lamp Contents 1 Lamp (electrical component) 1 1.1 Types ................................................. 1 1.2 Uses other than illumination ...................................... 2 1.3 Lamp circuit symbols ......................................... 2 1.4 See also ................................................ 2 1.5 References ............................................... 2 2 Incandescent light bulb 3 2.1 History ................................................. 3 2.1.1 Early pre-commercial research ................................ 4 2.1.2 Commercialization ...................................... 5 2.2 Tungsten bulbs ............................................. 6 2.3 Efficacy, efficiency, and environmental impact ............................ 8 2.3.1 Cost of lighting ........................................ 9 2.3.2 Measures to ban use ...................................... 9 2.3.3 Efforts to improve efficiency ................................. 9 2.4 Construction .............................................. 10 2.4.1 Gas fill ............................................ 10 2.5 Manufacturing ............................................. 11 2.6 Filament ................................................ 12 2.6.1 Coiled coil filament ...................................... 12 2.6.2 Reducing filament evaporation ................................ 12 2.6.3 Bulb blackening ........................................ 13 2.6.4 Halogen lamps ........................................ 13 2.6.5 Incandescent arc lamps .................................... 14 2.7 Electrical