UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TWP Connects Spring 2021

3710 Main Street IN THIS ISSUE: Kansas City, MO 64111 816-561-0304 2 CDS Update thewholeperson.org 3 Volunteering with TWP 4 2019/20 TWP Annual Report 5 Deaf Services Training TWP CONNECTS 6 Peer Support Groups SPRING 2021 NEWSLETTER ISSUE 21 7 Qualifying for SSDI 8 Contact Information Connecting people with disabilities to the resources they need 2021/2022 Expressions Art Exhibition The Show Must Go On! Gallery Schedule his year marks the 11th Annual Expressions Art Exhibition showcasing March, April, May artists with disabilities and celebrating their abilities and unique talents. Rochester Brewing and Roasting Co. TExpressions strives to promote artists with disabilities by featuring their June, July work in professionally organized art exhibitions and offering them innovative The Thornhill Gallery educational and networking workshops that connect them to the broad regional August, September, October creative community. Kansas City, Kansas Public Library South Branch The 2021 Expressions opening reception will be held March 5, from 11:00 am - November, December 2021; 7:00 pm at Rochester Brewing & Roasting Company, 2129 Washington Street, January, February 2022 Kansas City, Missouri. All current CDC Guidelines regarding the pandemic will Kansas City Kansas Community College be followed. The opening will feature both live and virtual events, and an online March 2022 gallery will be launched after March 5th. Kansas City Artists’ Coalition The exhibition will remain on display at multiple metro area venues through March 2022. Learn more -

Country Club Plaza

KANSAS CITY — MISSOURI COUNTRY CLUB PLAZA 4750 BROADWAY, KANSAS CITY, MISSOURI 64112 CULTURAL EPICENTER SELECT TENANTS — — Country Club Plaza is the dominant upscale shopping and dining destination in Kansas City. This one-of-a- kind, 15-block open air destination also serves as an urban cultural district offering long-standing yearly events and traditions. UNIQUE-TO-MARKET — Including Eileen Fisher, Free People, Kate Spade New York, Moosejaw, Sur La Table, Tiffany & Co., Vineyard Vines, Warby Parker and West Elm. DINING — Brio Tuscan Grille, Buca Di Beppo, Chuy’s Mexican Food, Classic Cup Cafe, Cooper’s Hawk Winery, Fogo de Chao, Gram & Dun, Granfalloon Restaurant & Bar, Hogshead Kansas City, Jack Stack Barbecue, McCormick & Schmick’s, O’Dowd’s Gastrobar, P.F. Chang’s, Parkway Social, Rye, Seasons 52, Shake Shack, The Capital Grille, The Cheesecake Factory, The Melting Pot, True Food Kitchen, Zocalo Mexican Cuisine and Tequileria and more. LOCATION — The Plaza is at the heart of where people live and work, with over 20 condominium communities within walking distance and many multi-million dollar homes within five miles of the Plaza. 2019 TRADE AREA DEMOGRAPHICs – 15-MILE RADIUS (SOURCES: CLARITAS, TETRAD, ENVIRONICS, ESRI) TOURISM ll rights reserved. A — Population ______________________ 1,337,953 Households ______________________ 551,630 Kansas City welcomed a record 25.2 million visitors in and its licensors are $75K+ Households _______________ 223,970 RI 2016 who spent $3.4 billion. S $100K+ Households ______________ 155,045 E and its licensors. Daytime Population ______________ 1,522,073 RI S In its 88th year, the Plaza Art Fair, recognized as one of —— E the top five art fairs in the U.S., is held during the third MALL TENANT SPACE week of September. -

Country Club Plaza Walking Guide

7 WAYS OF LOOKING AT THE PLAZA 50 NOTABLE THINGS TO SEE BY HISTORIC KANSAS CITY COUNTRY CLUB PLAZA WALKING GUIDE PUBLISHED WITH THE SUPPORT OF THE WILLIAM T. KEMPER FOUNDATION COUNTRY CLUB PLAZA WALKING GUIDE Introduction .................................................................... 3 7 Ways of Looking at the Plaza: A few words about the history and lasting value of Kansas City’s prized shopping district. Planning ........................................................................... 4 Architecture ..................................................................... 6 Business ............................................................................ 8 Placemaking .................................................................. 10 Neighborhood .............................................................. 12 Community ................................................................... 14 Legacy ............................................................................. 16 50 Notable Things to See: A Plaza Walking Guide: Towers, tiles and tucked-away details that make up the essence of the Country Club Plaza. Maps and details .....................................................18-33 A Plaza Timeline ..........................................................34 Acknowledgments ......................................................34 Picture credits ...............................................................34 About Historic Kansas City Foundation ...............35 2 INTRODUCTION TAKE A WALK By Jonathan Kemper n addition -

1625 Watt Avenue WATT AVENUE & ARDEN WAY, SACRAMENTO, CALIFORNIA

FOR SALE OR LEASE> ±9,584 SF FREESTANDING RESTAURANT BUILDING 1625 Watt Avenue WATT AVENUE & ARDEN WAY, SACRAMENTO, CALIFORNIA Highlights > ±9,584 square foot freestanding building > ±1.21 acre site with 71 parking spaces > Recently-renovated, fully improved restaurant building > High identity location in a prime retail trade area > Heavily-trafficked intersection, over 50,000 cars per day > Highly-visible monument and building signage > Strong residential and daytime population Traffic Count > Watt Avenue @ Arden Way: 50,084 ADT > Arden Way @ Watt Avenue: 22,124 ADT Demographic Snapshot 1 Mile 3 Miles 5 Miles Population 16,610 144,257 332,104 Daytime Population 18,687 166,145 383,255 Households 6,808 60,490 130,824 Average Income $80,656 $70,554 $66,946 Pricing > Sale Price: $2,200,000 > Lease Rate: $1.50/SF NNN (Estimated Operating Expenses: ±$0.50/SF) COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL MARK ENGEMANN MICHAEL DRAEGER San Francisco Peninsula [email protected] [email protected] 203 Redwood Shores Pkwy, Ste 125 +1 916 563 3007 +1 650 486 2221 Redwood City, CA 94065 CA License No. 00865424 CA License No. 01766822 colliers.com/redwoodcity FOR SALE OR LEASE> ±9,584 SF FREESTANDING RESTAURANT BUILDING 1625 Watt Avenue WATT AVENUE & ARDEN WAY, SACRAMENTO, CALIFORNIA Market Square Country Club Centre Country Club Plaza Arden & Watt Point West Plaza Arden Plaza Arden Square 1625 WATT AVENUE Arden Watt Marketplace MARK ENGEMANN MICHAEL DRAEGER [email protected] [email protected] +1 916 563 3007 +1 650 486 2221 CA License No. 00865424 CA License No. 01766822 FOR SALE OR LEASE> ±9,584 SF FREESTANDING RESTAURANT BUILDING 1625 Watt Avenue WATT AVENUE & ARDEN WAY, SACRAMENTO, CALIFORNIA EXISTING ADJACENT SINGLE STORY OFFICE BUILDING Site Plan PROJECT SUMMARY THIS PROJECT IS A PROPOSED RENOVATION OF AN EXISTING RESTAURANT BUILDING. -

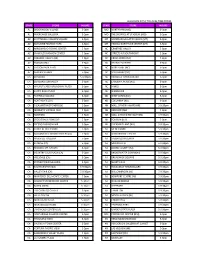

Store # Address 1 Address 2 City State 1 2837 WINCHESTER PIKE

Store # Address_1 Address_2 City State 1 2837 WINCHESTER PIKE BERWICK PLAZA COLUMBUS OH 3 PEACH ORCHARD PLAZA 2708 PEACH ORCHARD RD AUGUSTA GA 5 GREAT SOUTHERN S/C 3755 S HIGH STREET COLUMBUS OH 7 68 N WILSON ROAD GREAT WESTERN SC COLUMBUS OH 21 606 TAYWOOD ROAD NORTHMONT PLAZA ENGLEWOOD OH 29 918 EAST STATE STREET ATHENS SHOPPING CENTER ATHENS OH 30 818 S. MAIN STREET BOWLING GREEN OH 32 2800 WILMINGTON PIKE DAYTON OH 37 13 ACME STREET MARIETTA OH 39 2250 DIXIE HIGHWAY HAMILTON PLAZA HAMILTON OH 42 2523 GALLIA STREET PORTSMOUTH OH 43 3410 GLENDALE AVE. SOUTHLAND SHOPPING CENTER TOLEDO OH 45 3365 NAVARRE AVENUE OREGON OH 49 825 MAIN STREET MILFORD OH 51 1090 MILLWOOD PIKE WINCHESTER VA 57 OAKHILL PLAZA S/C 3041 MECHANICSVILLE TURNPIKE RICHMOND VA 58 370 KROGER CENTER MOREHEAD KY 61 800 14TH STREET W. HUNTINGTON WV 62 1228 COUNTRY CLUB ROAD COUNTRY CLUB PLAZA FAIRMONT WV 64 127 COMMERCE AVE COMMERCE VILLAGE S/C LAGRANGE GA 71 1400 S. ARLINGTON STREET ARLINGTON PLAZA AKRON OH 72 3013 NORTH STERLING AVE WARDCLIFFE S/C PEORIA IL 77 1615 MARION-MT. GILEAD ROAD FORUM SHOPPING CENTER MARION OH 78 3600 S DORT HIGHWAY #58 MID-AMERICA PLAZA FLINT MI 79 1140 PARK AVENUE WEST MANSFIELD OH 82 1350 STAFFORD DRIVE PRINCETON WV 83 1211 TOWER BLVD. LORAIN OH 86 ALTON SQUARE SHOPPING CTR 1751 HOMER ADAMS PARKWAY ALTON IL 91 5520 MADISON AVE INDIANAPOLIS IN 97 1900 BRICE RD BRICE POINT REYNOLDSBURG OH 98 498 CADIZ RD STEUBENVILLE OH 102 27290 EUREKA ROAD CAMBRIDGE SQUARE TAYLOR MI 109 15 E 6TH STREET BELLEVUE PLAZA BELLEVUE KY 111 5640 N. -

Foundations of OUR

the volume 70 H issue 7 H 10 march 2011 ST. TERESA’S ACADEMY foundations OF OUR St. Teresa’s will celebrate the groundbreaking ceremony for the new chapel of St. Josephfaith and Windmoor Center March 23. This fourth building, which will complete the Quad of the Little Flower, is the newest addition to the school’s 101-year history on campus. See pages 10-11. photo by SARAH WIRTZ 2 in focus the dart H st. teresa’s academy H 10 march 2011 dartnewsonline.com the Dart staff Snow days unlikely to change schedule Adviser MR. ERIC THOMAS Administration defines snow day Editor-in-Chief requirements, students, teachers MORGAN SAID cope with possible reprecussions Print Staff: story by ROWAN O’BRIEN-WILLIAMS Managing Editor of Print: MEGAN SCHAFF academics editor Managing Editor of Copy: KATIE HYDE News Editor: CHELSEA BIRCHMIER Opinion Editor: CHRISTINA BARTON STA’s schedule, allowing for five snow days, will Lifestyles Editors: KATE ROHR, CELIA not change after exactly five snow days this year, O’FLAHERTY Centerspread Editor: MADALYNE BIRD according to principal for student affairs Mary Anne Sports Editor: CASSIE REDLINGSHAFER schedule.Hoecker. This means that second semester finals, Entertainment Editor: LAURA NEENAN graduation and the last day of school are still on - Features Editor: HANNAH WOLF Academics Editor: ROWAN O’BRIEN- According to principal for academic affairs Bar WILLIAMS bara McCormick, students will be in school 174 days, In the Mix Editor: KATHLEEN HOUGH meeting Missouri’s requirements. Last Look Editor: SARA MEURER These requirements do not apply to private or Staff Writers: EMILY BRESETTE, LANE parochial schools, according to MO.gov, the official - MAGUIRE, EMILY McCANN, MARY Missouri state website. -

Store Number

Store Number STORE NAME State 0788 ANCHORAGE AK 0124 BIRMINGHAM AL 0140 RIVERCHASE GALLERIA AL 0724 HUNTSVILLE AL 0132 PINNACLE HILLS AR 0488 LITTLE ROCK AR 0016 BILTMORE AZ 0094 ARROWHEAD AZ 0168 SAN TAN VILLAGE AZ 0288 CHANDLER AZ 0364 SCOTTSDALE AZ 0480 TUCSON AZ 0736 THE QUARTER AZ 0926 PARK PLACE AZ 1258 DANA PARK AZ 1308 NORTERRA AZ 0026 SANTA MONICA CA 0028 HILLSDALE CA 0030 ANAHEIM CA 0032 HOLLYWOOD & HIGHLAND CA 0034 PASADENA CA 0036 FASHION VALLEY CA 0038 UNIVERSITY TOWNE CENTER CA 0048 STANFORD CA 0052 BURLINGAME CA 0058 POWELL STREET CA 0078 CENTURY CITY CA 0082 RANCHO CUCAMONGA CA 0088 FRESNO FASHION FAIR CA 0090 SANTA BARBARA CA 0104 BAKERSFIELD CA 0116 EMERYVILLE CA 0196 UNION STREET CA 0202 WALNUT CREEK CA 0206 NOVATO CA 0232 OTAY RANCH CA 0382 EMBARCADERO CA 0438 SAN LUIS OBISPO CA 0462 PACIFIC COMMONS CA 0484 MODESTO CA 0494 TEMECULA CA 0614 CALABASAS CA 0646 VALENCIA CA 0672 AMERICANA CA 0674 PALM DESERT CA 0740 MALIBU CA 0914 HUNTINGTON BEACH CA 0922 MARINA DEL REY CA 0928 BEVERLY DRIVE CA 0934 MONTEREY CA 0938 WESTLAKE CA 0946 THE GROVE CA 0958 SANTANA ROW CA 1118 RIVER PARK CA 1128 CORTE MADERA TOWN CENTER CA 1134 CONCORD CA 1138 UNIVERSAL CITY WALK CA 1144 STUDIO CITY CA 1150 CHINO HILLS CA 1158 TUSTIN MARKET PLACE CA 1166 PACIFIC PALISADES CA 1168 LAUREL VILLAGE CA 1172 DALY CITY CA 1176 ALISO VILLAGE CA 1190 FOLSOM CA 1192 SANTEE CA 1200 BERKELEY CA 1202 SAN FRANCISCO CENTRE CA 1218 PALM SPRINGS CA 1222 ONE PASEO CA 1230 IRVINE SPECTRUM CA 1236 REDLANDS CA 1240 BISHOP RANCH CA 1250 LONG BEACH CA 1268 SHOPPES AT -

State Store Hours State Store Hours Al Brookwood

ALL HOURS APPLY TO LOCAL TIME ZONES STATE STORE HOURS STATE STORE HOURS AL BROOKWOOD VILLAGE 5-9pm MO NORTHPARK (MO) 5-9pm AL RIVERCHASE GALLERIA 5-9pm MO THE SHOPPES AT STADIUM (MO) 5-9pm AZ SCOTTSDALE FASHION SQUARE 5-9pm MT BOZEMAN GALLATIN VALLEY (MT) 5-9pm AZ BILTMORE FASHION PARK 5-9pm MT HELENA NORTHSIDE CENTER (MT) 5-9pm AZ ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER 5-9pm NC CRABTREE VALLEY 5-9pm AZ CHANDLER FASHION CENTER 5-9pm NC STREETS AT SOUTHPOINT 5-9pm AZ PARADISE VALLEY (AZ) 5-9pm NC CROSS CREEK (NC) 5-9pm AZ TUCSON MALL 5-9pm NC FRIENDLY CENTER 5-9pm AZ TUCSON PARK PLACE 5-9pm NC NORTHLAKE (NC) 5-9pm AZ SANTAN VILLAGE 5-9pm NC SOUTHPARK (NC) 5-9pm CA CONCORD 5-9:30pm NC TRIANGLE TOWN CENTER 5-9pm CA CONCORD SUNVALLEY 5-9pm NC CAROLINA PLACE (NC) 5-9pm CA WALNUT CREEK BROADWAY PLAZA 5-9pm NC HANES 5-9pm CA SANTA ROSA PLAZA 5-9pm NC WENDOVER 5-9pm CA FAIRFIELD SOLANO 5-9pm ND WEST ACRES (ND) 5-9pm CA NORTHGATE (CA) 5-9pm ND COLUMBIA (ND) 5-9pm CA PLEASANTON STONERIDGE 5-9pm NH MALL OF NEW HAMPSHIRE 5-9:30pm CA MODESTO VINTAGE FAIR 5-9pm NH BEDFORD (NH) 5-9pm CA NEWPARK 5-9pm NH MALL AT ROCKINGHAM PARK 5-9:30pm CA STOCKTON SHERWOOD 5-9pm NH FOX RUN (NH) 5-9pm CA FRESNO FASHION FAIR 5-9pm NH PHEASANT LANE (NH) 5-9:30pm CA SHOPS AT RIVER PARK 5-9pm NJ MENLO PARK 5-9:30pm CA SACRAMENTO DOWNTOWN PLAZA 5-9pm NJ WOODBRIDGE CENTER 5-9:30pm CA ROSEVILLE GALLERIA 5-9pm NJ FREEHOLD RACEWAY 5-9:30pm CA SUNRISE (CA) 5-9pm NJ MONMOUTH 5-9:30pm CA REDDING MT. -

2005 Presidential Scholars (PDF)

2005 Presidential Scholars May 2005 * An asterisk indicates a Presidential Scholar in the Arts Alabama AL - Anniston - Lance J. Collins, Alabama School of Fine Arts AL - Beatrice - Lydia C. Hardee, Monroe Academy Alaska AK - Anchorage - Morgan M. Jessee, East Anchorage High School AK - Kodiak - Matthew P. Mudd, Home School Americans Abroad AP - APO - Mark A. Norsworthy, Lakenheath High School AP - Oxford - Elizabeth A. MacFarlane, Phillips Exeter Academy Arizona AZ - Gilbert - Kevin Z. Jiang, Mesquite High School AZ - Tempe - Marilynn A. Ly, Corona del Sol High School Arkansas AR - Fort Smith - Nicholas H. Schluterman, Southside High School AR - North Little Rock - Natalie N. Greene, North Little Rock High School - West Campus California *CA - Berkeley - L. Isaak Brown, Idyllwild Arts Academy CA - Oak Park - Sabrina Chou, La Reina High School CA - Rancho Mirage - Blair J. Greenwald, Palm Springs High School CA - Saratoga - Aman I. Kumar, Crystal Springs Uplands School *CA - Sherman Oaks - Rachel E. Rosenstein-Sisson, Marlborough School Colorado CO - Broomfield - Suguna P. Narayan, Thornton High School CO - Denver - Alexander R. White, Kent Denver School *CO - Fort Collins - Joel C. Atella, Rocky Mountain High School CO - Golden - Irina D. Hardesty, Gilpin County R. E. I. High School *CO - Parker - Colin J. Stranahan, Denver School of the Arts Connecticut CT - Hamden - Charles G. Nathanson, Hamden High School CT - Wethersfield - Caitlin M. Drake, Wethersfield High School Delaware DE - Hockessin - Stephen T. Biederman, Wilmington Christian School DE - Wilmington - Natasha M. Platt, Concord High School District of Columbia DC - Washington - Cullen O. Macbeth, St. Alban's School DC - Washington - Kathryn A. Ray, Sidwell Friends School Florida FL - Fort Lauderdale - Andrew L. -

Beautiful and Damned: Geographies of Interwar Kansas City by Lance

Beautiful and Damned: Geographies of Interwar Kansas City By Lance Russell Owen A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Michael Johns, Chair Professor Paul Groth Professor Margaret Crawford Professor Louise Mozingo Fall 2016 Abstract Beautiful and Damned: Geographies of Interwar Kansas City by Lance Russell Owen Doctor of Philosophy in Geography University of California, Berkeley Professor Michael Johns, Chair Between the World Wars, Kansas City, Missouri, achieved what no American city ever had, earning a Janus-faced reputation as America’s most beautiful and most corrupt and crime-ridden city. Delving into politics, architecture, social life, and artistic production, this dissertation explores the geographic realities of this peculiar identity. It illuminates the contours of the city’s two figurative territories: the corrupt and violent urban core presided over by political boss Tom Pendergast, and the pristine suburban world shaped by developer J. C. Nichols. It considers the ways in which these seemingly divergent regimes in fact shaped together the city’s most iconic features—its Country Club District and Plaza, a unique brand of jazz, a seemingly sophisticated aesthetic legacy written in boulevards and fine art, and a landscape of vice whose relative scale was unrivalled by that of any other American city. Finally, it elucidates the reality that, by sustaining these two worlds in one metropolis, America’s heartland city also sowed the seeds of its own destruction; with its cultural economy tied to political corruption and organized crime, its pristine suburban fabric woven from prejudice and exclusion, and its aspirations for urban greatness weighed down by provincial mindsets and mannerisms, Kansas City’s time in the limelight would be short lived. -

Competitive Snapshot

PHASE 1: COMPETITIVE SNAPSHOT Submitted by Market Street Services Inc. www.marketstreetservices.com April 24, 2012 Table of Contents Project overview....................................................................................................................................................................................... 2 Executive Summary ................................................................................................................................................................................ 3 People ........................................................................................................................................................................................................ 13 Community Growth ....................................................................................................................................................................... 13 Age Dynamics .................................................................................................................................................................................. 16 Diversity .............................................................................................................................................................................................. 18 Educational Attainment ............................................................................................................................................................... 22 Income ............................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Community Features in the Country Club District

Building Character and Distinction Community Features in the Country Club District Community features can and should be the means of giving character and distinction to your property; the things that create enthusiasm and a liking for the property by its residents; the things that cause your cli- ents and your owners in your property to enjoy living there. Community features … include the activities that bring residents … to- gether in any united purpose of pleasant or serious effort. On the other hand, it includes the character of the physical development of your property, its adornment, its characteristics — the very creation of an individual and an appealing personality in all or various parts of your property … These features may be the inspiration that causes a better Mary Rockwell Hook was Kansas City’s and more intensive development of every private lawn; an inspiration first significant female architect. Here for better architecture … the cause of the development of a greater in- she is pictured heading off to France in terest and love of one’s home … the cause for closer friendships, and a 1920 to work for the American Com- greater neighborhood and community spirit. They directly improve life mittee for Devastated France. Her work is in its noblest sense and lead to higher aspirations to obtain the things important but little known. See story on worthwhile in life — and in the end, from it all comes a greater love page 9. and respect for one’s city, a greater civic interest and pride, a better public spirit, and a greater patriotism for city and nation in the hearts of both young and old.