HDR- Albania 2005

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INTERVIEW with SHYQRI NIMANI Pristina | Data: November 30, 2016 Duration: 70 Minutes

INTERVIEW WITH SHYQRI NIMANI Pristina | Data: November 30, 2016 Duration: 70 minutes Present: 1. Shyqri Nimani (Speaker) 2. Erëmirë Krasniqi (Interviewer) 3. Noar Sahiti (Camera) Transcription notation symbols of non-verbal communication: () – emotional communication {} – the speaker explains something using gestures. Other transcription conventions: [ ] - addition to the text to facilitate comprehension Footnotes are editorial additions to provide information on localities, names or expressions. Part One [The interviewer asks the speaker about his early memories. This part was cut from the video—interview.] Shyqri Nimani: I would like to tell you the story of my life and the crucial moments that made me choose figurative art. Destiny was such that I was born in Shkodra because my family, my mother and father moved there before the Second World War, they moved to Albania and settled in Shkodra. That’s where I was born. Two years later we moved to Skopje where my brother Genc was born and after two other years we moved to Prizren and then from Prizren we moved to Gjakova, which was the hometown of my mother and my father, then I continued elementary school in Prizren. And the Shkolla e Mesme e Artit1 in the beautiful Peja, after five years of studying there I went to University at the University of Arts in Belgrade, there I spent five years studying in the same academy. Then, I finished the Masters Degree, I mean the post—graduation studies and in the meantime there was an open call all around Yugoslavia according to which the Japanese government was giving a scholarship for a two year artistic residency in Japan, I won it and went to Japan to study for two years. -

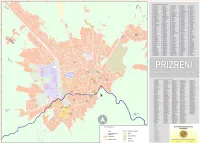

Map Data from the City of Prizren For

1 E E 3 <*- * <S V to v-v % X % 5.- ^s RADHITJA E EMRAVE SIPAS ALFABETIT -> 42 8 Marsi-7D 443 Brigáda 126-4C 347 Hysen Rexhepi-6E7E 253 Milan Šuflai-3H 218 Shaip Zurnaxhiu-4F 187 Abdy Beqiri-4E 441 Brigáda 128- 234 Hysen Trpeza-2E H 356 Mimar Sinan-6E 133 Shat Kulla-6E 1 Adem Jasharí-6E,5F 20 Bubulina-1A 451 Hysni Morína-3B 467 Mojsi Golemi-2A, 2B 424 Shefqet Berisha-80 | 360 Adnan Krasniqi-7E 97 Bujana-2D 46 Hysni Temaj- 25 Molla e Kuqe 390 Sheh Emini-7D 310 Adriatiku-5F 327 Bujar Godeni-6E 127 Ibrahim Lutfiu-6D 72 Mon Karavidaj-3C3D 341 Shn Albani-7F 38 Afrim Bytygi-1B,2B 358 Bujtinat-6E, 7E 259 Ibrahim ThagiSH 184 Morava-4E \J336 Shn Flori-6F, 7F 473 Afrim Krasniqi-9C 406 Burími-8D 45 Idriz Behluli- 23 Mreti Gllauk-1A \~345 Shn Jeronimi 1 444 Afrim Stajku-4C 261 Bushatlinjt-2H 39 llir Hoxha-1B 265 Muhamet Cami~3H 284 SherifAg TurtullaSG 446 Agim Bajrami-4C 140 Byrhan Shporta-6D 233 llirt-2E 21 Muhamet Kabashi-1A 29 Shestani | 278 Agim ShalaSF 47 Camilj Siharic 359 lljaz Kuka-6E,7E 251 Muharrem Bajraktarí-2H,3E 243 Shime Deshpali-2E 194 Agron Bytyqi-4E 56 Cesk Zadeja-3C 381 Indrit Cara -Kavaja-6D, 7D 74 Muharrem Hoxhaj-3C 291 Shkelzen DragajSF 314 Ahmet KorenicaSF 262 Dalmatt-3H 86 Isa Boletini-4D 458 Muharrem Samahoda-3B 199 Shkodra-3E \~286 293 Ahmet KrasniqiSF 475 Dardant-9C Islám Spahiu-5G l 316 MuhaxhirtSF \428 Shkronjat-7C, 7D 207 \Ahmet Prístina-5F4F 5 De Rada-6D, 5D \~7 Ismail Kryeziu-5D,4D 60 Mujo Ulqinaku-3C 138 Shote Galica-6D 447 Ajahidet-4C 61 Dd Gjon Luli-3C 40 Ismail Qemali-2B 1 69 Murat Kab ashi-4F, 5E 392 Shpend Berisha-7E -

Alfred Moisiu (Alfred Spiromoisiu)

Alfred Moisiu (Alfred SpiroMoisiu) Albania, Presidente de la República Duración del mandato: 24 de Julio de 2002 - de de Nacimiento: Shkodër, distrito de Shkodër, 01 de Diciembre de 1929 Partido político: sin filiación Profesión : Militar Resumen http://www.cidob.org 1 of 3 Biografía Hijo de un militante comunista, siendo un muchacho tomó parte en la lucha partisana contra los alemanes en los dos últimos años de la Segunda Guerra Mundial y en 1946, al poco de instaurarse el régimen marxista de Enver Hoxha, las autoridades le becaron para recibir educación superior en la URSS. En 1948 se graduó en la Escuela Militar de Ingenieros de San Petersburgo (entonces Leningrado), posteriormente desempeñó en Tirana diversas funciones de instrucción y mando de tropa y de 1952 a 1958 realizó estudios de perfeccionamiento en la Academia de Ingeniería Militar de Moscú. De vuelta a Albania y luego de romper el dictador Hoxha con el sistema soviético por la desestalinización lanzada por Krushchev, Moisiu prosiguió su ascensión como militar de carrera en la sección de ingenieros del Ministerio de Defensa. Entre 1967 y 1968 siguió en la Academia Militar de Tirana un curso para oficiales del Estado Mayor del Ejército al tiempo que comandaba una brigada de pontoneros en Kavaja. Desde 1971 dirigió la oficina de Ingeniería y Fortificaciones del Ministerio de Defensa (un aspecto esencial en el régimen paranoico de Hoxha, quien sembró el pequeño país de millares de casamatas de hormigón en previsión de una invasión de cualquiera de los muchos países que él tenía por enemigos) y en 1981 recibió el rango de viceministro, sirviendo a las órdenes sucesivamente de los ministros Beqir Balluku, Mehmed Shehu y Kadri Hasbiu. -

SHËNJTORI ARBËR QË U «KRYQËZUA» PËR TË VËRTETËN Nga Fatbardha Demi Shprehja: “Ku Shkel Turku Nuk Mbin Bar”

pagina 1 Anno 17 n.5 Dicembre 2019 Anno 17 Distribuzione gratuita in: Mensile di attualità e cultura italo-albanese Albania, Australia, Numero 5 Belgio, Canada, Germania, Direttore editoriale: Hasan Aliaj Grecia, Francia, Italia, Dicembre 2019 Stati Uniti e Svizera Ky fakt dëshmohet nga objektet arkeologjike, simbolet e besimit të tyre hënor etj. që i Njeriu ka përmasat Shënjtori Arbër huazuanqë edheu pushtuesit «kryqëzua» tartaro-mongol. për të vërtetën e gjuhës Nga FATBARDHA DEMI Nga Dr.LEDI SHAMKU eprimtaria e Mihal Trivolit në Rusi s’do të njihej në shumëllojshmërinë dhe o e nis duke thënë se vjeshta e vitit 2019 Vrëndësinë e saj, po të mos ishin zbuluar në të cilën ndodhemi është vjeshtë për- rastësisht në vitin 1968 nga N.Pokrovski (Н. Н. Pkimesh (koicidencash), dhe se Epikyri Покровски) dosjet e tij gjyqësore në Altae të na thotë se quajmë ashtu shkurt “përkim a Siberisë. (1) Ky zbulim ka një rëndësi të jashtë- koincidencë” cdo dukuri të cilën hëpërhë nuk zakonshme, sepse «krimet» e Mihalit, shpalosin mundemi ose nuk duam ta ftillojmë. jetën fetare dhe shoqërore të Rusisë së shek.15- 16... (lexo në faqen 7 (lexo në faqen 2) a-Amuletë me simbolin e besimit hënor të pellazgëve (Sellenizmit), Gochevo, Rusia e jugut, Një protestë Gëzuar Festën shk.11;Në b. Hënavendin dhe simboli ie 3 fazavepaqes të saj (trinita së kristiane) Nënës të varura së më poshtë. Madhe, shk.8; c. Simboli i besimit hënor në vëthet nga Helladak (Eleusi)ëtë kukuvaj e shk.8ë pK.si mama(5) të Athinas e kemi pendime bëjnë sipAinetiaër në bimën eduke ullirit. -

Coordinating for Gender Equality Results

COORDINATING FOR GENDER EQUALITY RESULTS RESULTS GENDER EQUALITY FOR COORDINATING COORDINATING FOR GENDER EQUALITY RESULTS Regional evaluation of UN Women’s contribution to UN system coordination on gender equality and the empowerment of women in Europe and Central Asia ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The evaluation team wishes to thank the many individuals UN Women ECA RO Regional Director, Alia El-Yassir, and organizations who supported the evaluation process UN Women ECA RO Deputy Director and Fumie Nakamura, by making themselves available for interviews and surveys UN Women ECA RO Coordination and Planning Specialist. and by providing helpful feedback on draft deliverables. Special thanks to the UN Women Europe and Central We thank the country representatives and staff of the Asia Regional Office (ECA RO) and to UN Women country four offices visited for all the dedicated time they invested offices, government and non-government partners in the in supporting the evaluation process and in facilitating four case study countries (Albania, Kyrgyzstan, Kosovo, the engagement and inclusion of a wide range of part- and Turkey) and the three countries interviewed virtually ners, stakeholders and beneficiaries of their work, in (Bosnia-Herzegovina, Georgia, and Serbia) for this evalua- particular Albania Country Office (David Saunders, tion. Their cooperation was essential in understanding the Country Office Representative), Kyrgyzstan Country Office nature of UN Women’s coordination mandate at regional (Gerald Gunther, Country Office Representative), Kosovo and national levels. We are also grateful to all 14 ECA Programme Office (Flora Macula, Head of Programme countries whose documentation was provided for review. Office), Turkey Programme Office (Zeliha Unaldi, Gender Finally, we could not have done this without the support Specialist Office of the UN Resident) Coordinator). -

Baseline Assessment Report of the Lake Ohrid Region – Albania Annex

TOWARDS STRENGTHENED GOVERNANCE OF THE SHARED TRANSBOUNDARY NATURAL AND CULTURAL HERITAGE OF THE LAKE OHRID REGION Baseline Assessment report of the Lake Ohrid region – Albania (available online at http://whc.unesco.org/en/lake-ohrid-region) Annex XXIII Bibliography on cultural values and heritage, agriculture and tourism aspects of the Lake Ohrid region prepared by Luisa de Marco, Maxim Makartsev and Claudia Spinello on behalf of ICOMOS. January 2016 BIBLIOGRAPHY1 2015 The present bibliography focusses mainly on the cultural values and heritage, agriculture and tourism aspects of the Lake Ohrid region (LOR). It should be read in conjunction to the Baseline Assessment report prepared in a joint collaboration between ICOMOS and IUCN (available online at http://whc.unesco.org/en/lake-ohrid-region) The bibliography includes all the relevant titles from the digital catalogue of the Albanian National Library for the geographic terms connected to LOR. The bibliography includes all the relevant titles from the systematic catalogue since 1989 to date, for the categories 9-908; 91-913 (4/9) (902. Archeology; 903. Prehistory. Prehistoric remains, antiquities. 904. Cultural remains of the historic times. 908. Regional studies. Studies of a place. 91. Geography. The exploration of the land and of specific places. Travels. Regional geography). It also includes the relevant titles found on www.scholar.google.com with summaries if they are provided or if the text is available. Three bibliographies for archaeology and ancient history of Albania were used: Bep Jubani’s (1945-1971); Faik Drini’s (1972-1983); V. Treska’s (1995-2000). A bibliography for the years 1984-1994 (authors: M.Korkuti, Z. -

Albania Pocket Guide

museums albania pocket guide your’s to discover Albania theme guides Museums WELCOME TO ALBANIA 4 National Historic Museum was inaugurated on 28 October 1981. It is the biggest Albanian museum institution. There are 4750 objects inside the museum. Striking is the Antiquity Pavilion starting from the Paleolithic Period to the Late Antiquity, in the 4th century A.D., with almost 400 first class objects. The Middle Age Pavilion, with almost 300 objects, documents clearly the historical trans- formation process of the ancient Illyrians into early Arbers. CONTENTS i 5 TIRANA 6 DURRES 14 ELBASAN 18 LUSHNJE 20 KRUJE 20 APOLLONIA 26 VLORA 30 KORÇA 34 GJIROKASTRA 40 BERATI 42 BUTRINTI 46 LEZHE 50 SHKODER 52 DIBER 60 NATIONAL HISTORIC MUSEUMS TIRANA 6 National Historic Museum was inaugurated on 28 October 1981. It is the biggest Albanian museum institution. Pavilion starting from the Paleolithic Period to the Late Antiquity, in the 4th century A.D., with almost 400 first class objects. The Middle Age Pavilion, with almost 300 objects, documents clearly the historical transformation process of the ancient Illyrians into early Arbers. This pavilion reflects the Albanian history until the 15th century. Other pavilions are those of National Renaissance, Independence and Albanian State Foundation, until 1924. The Genocide Pavilion with 136 objects was founded in 1996. The Iconography Pavilion with 65 first class icons was established in 1999. The best works of 18th and 19th century painters are found here, like Onufër Qiprioti, Joan Çetiri, Kostandin Jermonaku, Joan Athanasi, Kostandin Shpataraku, Mihal Anagnosti and some un- known authors. In 2004 the Antifascism Pavilion 220 objects was reestablished. -

Albanian Migrant Women

Albanian migrant women Relation between migration and empowerment of women. The case-study of Albania A Bachelor Thesis Subject: Migration and the empowerment of women Title: Relation between migration and the empowerment of women. The case-study of Albania. Thesis supervisor: Dr. Bettina Bock Student: Liza Iessa Student ID: 870806532080 Date: 30 May 2014 City: Wageningen Institute: University of Wageningen Program: International Development Studies Abstract This is an explorative research of the determinants of migration for women who come from male dominant societies and migrate to more equal societies. The main theory used is the theory of the push and pull factor. The oppression of women in dominantly male societies is defined as a push factor. And opportunities for self-empowerment in more equal societies are defined as a pull factor. In Albania men are the ones who become the head of the household and only men are allowed to own any property. According to the Kanun any women that act in any way as a dishonourable person should be punished or even should pay with her blood. In male dominated societies, such as Albania, there a only few opportunities for women to climb the ladder in the labour market. It makes it very hard for women to provide for themselves and their families financially. Escape high levels of gender inequality is defined as an important reason for Albanian women to migrate. After the fall of the communist regime in the 90’s, the national borders opened up and migration from Albania has increased tremendously. Some women escape male dominant society by migrating to regions with relatively more equality in gender relations. -

Women Entrepreneurs in Albania

SEED Working Paper No. 21 InFocus Programme on Boosting Employment through Small EnterprisE Development Job Creation and Enterprise Department Series on Women’s Entrepreneurship Development and Gender in Enterprises — WEDGE Women Entrepreneurs in Albania by Mimoza Bezhani International Training Centre of the ILO, International Labour Office · Geneva Turin, Italy Copyright © International Labour Organization 2001 First published 2001 Publications of the International Labour Office enjoy copyright under Protocol 2 of the Universal Copyright Convention. Nevertheless, short excerpts from them may be reproduced without authorization, on condition that the source is indicated. For rights of reproduction or translation, application should be made to the Publications Bureau (Rights and Permissions), International Labour Office, CH-1211 Geneva 22, Switzerland. The International Labour Office welcomes such applications. Libraries, institutions and other users registered in the United Kingdom with the Copyright Licensing Agency, 90 Tottenham Court Road, London W1T 4LP [Fax: (+44) (0)20 7631 5500; e-mail: [email protected]], in the United States with the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923 [Fax: (+1) (978) 750 4470; e-mail: [email protected]] or in other countries with associated Reproduction Rights Organizations, may make photocopies in accordance with the licences issued to them for this purpose. ILO Women Entrepreneurs in Albania Geneva, International Labour Office, 2001 ISBN 92-2-112758-3 Based on original document: Biznesi i Gruas në Shqipëri = L’imprenditorialità femminile in Albania, published by the International Training Centre of the ILO, Turin, 1999 (without ISBN). The designations employed in ILO publications, which are in conformity with United Nations practice, and the presentation of material therein do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the International Labour Office concerning the legal status of any country, area or territory or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers. -

Gjoka Konstruksion

143 www.rrugaearberit.com GAZETË E PAVARUR. NR. 3 / 2018. ÇMIMI: 50 LEKË. 20 DENARË. 1.5 EURO. Intervistë Art Profil Dr. Ahmet Alliu, Bajram Mata zgjodhi Pajtim Beça, një mjeku i parë i Dibrës të jetojë me fjalën e histori suksesi në Historiku i shërbimit shëndetësor në veprat e realizuara breg të Drinit optikën e mjekut të parë dibran Nga prof.as.dr.Nazmi KOÇI 16 Nga Selami NAZIFI 12 Nga Osman XHILI 9 NË BRENDËSI: Rruga e Arbrit: Qeveria firmos kontratën, Jemi skeptike për aq kohë sa nuk ka transparencë për fondet dhe projektin “Gjoka Konstruksion” gati të nisë punën Rruga e Arbrit i bashkon shqiptarët Dhjetë arsye përse duhet vizituar Dibra Rafting lumenjve të Dibrës që s’bëzajnë “FERRA E PASHËS” Jashar Bunguri, gjeneral i bujqësisë shqiptare Kastrioti, fshati pa Kastriotë Asllan Keta: Më shumë se Partinë, dua Shqipërinë Tenori Gerald Murrja: Ëndrra ime është të këndoj në skenat e operave në botë Shkolla Pedagogjike e Peshkopisë, tempull i dijes dhe edukimit Mustafa Shehu, një zemër Lexoni në faqen 2 që skaliti me zjarr emrin e tij në histori REPORTAZH SPORT: Alia dhe Halili, dy dibranët e Kombëtares U-19 Fadil Shulku, portieri modern i kohës Cerjani, një fshat Drini Halili:Objektivi është Kombëtarja!. Shqiponja dibrane i braktisur dhe i Marko Alia: Mes Italisë dhe Shqipërisë zgjodha vendin tim! Njerëz që hynë dhe mbetën në kujtesën e dibranëve rrënuar nga migrimi Islamil Hida, njeri i edukuar, fjalëpak e punëshumë Më shumë mund të shikoni në faqen e gazetës Nga BESNIK LAMI në FB: Rruga e Arbërit ose ndiq linkun: https://tinyurl.com/lcc3e2f erjani është një nga katër fshatrat e zonës së CBellovës që shtrihet në verilindje të qytetit të Peshkopisë, rreth 7 km larg tij. -

Behind Stone Walls

BEHIND STONE WALLS CHANGING HOUSEHOLD ORGANIZATION AMONG THE ALBANIANS OF KOSOVA by Berit Backer Edited by Robert Elsie and Antonia Young, with an introduction and photographs by Ann Christine Eek Dukagjini Balkan Books, Peja 2003 1 This book is dedicated to Hajria, Miradia, Mirusha and Rabia – girls who shocked the village by going to school. 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface Berita - the Norwegian Friend of the Albanians, by Ann Christine Eek BEHIND STONE WALLS Acknowledgement 1. INTRODUCTION Family and household Family – types, stages, forms Demographic processes in Isniq Fieldwork Data collection 2. ISNIQ: A VILLAGE AND ITS FAMILIES Once upon a time Going to Isniq Kosova First impressions Education Sources of income and professions Traditional adaptation The household: distribution in space Household organization Household structure Positions in the household The household as an economic unit 3. CONJECTURING ABOUT AN ETHNOGRAPHIC PAST Ashtu është ligji – such are the rules The so-called Albanian tribal society The fis The bajrak Economic conditions Land, labour and surplus in Isniq The political economy of the patriarchal family or the patriarchal mode of reproduction 3 4. RELATIONS OF BLOOD, MILK AND PARTY MEMBERSHIP The traditional social structure: blood The branch of milk – the female negative of male positive structure Crossing family boundaries – male and female interaction Dajet - mother’s brother in Kosova The formal political organization Pleqësia again Division of power between partia and pleqësia The patriarchal triangle 5. A LOAF ONCE BROKEN CANNOT BE PUT TOGETHER The process of the split Reactions to division in the family Love and marriage The phenomenon of Sworn Virgins and the future of sex roles Glossary of Albanian terms used in this book Bibliography Photos by Ann Christine Eek 4 PREFACE ‘Behind Stone Walls’ is a sociological, or more specifically, a social anthropological study of traditional Albanian society. -

Pakistan Journal of Botany

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/313842333 RELIGIOUS DIFFERENCES AFFECT ORCHID DIVERSITY OF ALBANIAN GRAVEYARDS Article · February 2017 CITATIONS READS 4 142 7 authors, including: Attila Molnár V. Zoltán Barina University of Debrecen Hungarian Natural History Museum 157 PUBLICATIONS 610 CITATIONS 64 PUBLICATIONS 361 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Gábor Sramkó Jácint Tökölyi Hungarian Academy of Sciences University of Debrecen 92 PUBLICATIONS 495 CITATIONS 43 PUBLICATIONS 284 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: Hydra Eco-Evo-Devo View project NKFIH K-119225 - How can plant ecology support grassland restoration? View project All content following this page was uploaded by Attila Molnár V. on 19 February 2017. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file. Pak. J. Bot., 49(1): 289-303, 2017. RELIGIOUS DIFFERENCES AFFECT ORCHID DIVERSITY OF ALBANIAN GRAVEYARDS ATTILA MOLNÁR V.1,2*, ATTILA TAKÁCS1,2, EDVÁRD MIZSEI3, VIKTOR LÖKI1, ZOLTÁN BARINA4, GÁBOR SRAMKÓ1,2 AND JÁCINT TÖKÖLYI5 1Department of Botany, University of Debrecen, Egyetem tér 1., H-4032, Debrecen, Hungary 2MTA-DE “Lendület” Evolutionary Phylogenomics Research Group, University of Debrecen, Egyetem tér 1., H-4032, Debrecen, Hungary 3Department of Evolutionary Zoology, University of Debrecen, Egyetem tér 1., H-4032, Debrecen, Hungary 4Department of Botany, Hungarian Natural History Museum, H-1431 Budapest, Pf. 137, Hungary 5MTA-DE “Lendület” Behavioural Ecology Research Group, University of Debrecen, Egyetem tér 1., H-4032, Debrecen, Hungary *Corresponding author’s email: [email protected], Phone: +36-52-/512-900/62648 ext.