For the Love of Gatsby

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

3RD AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARDS Winners by Category

3RD AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARDS Winners by Category AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARD FOR BEST FILM 12 YEARS A SLAVE AMERICAN HUSTLE CAPTAIN PHILLIPS GRAVITY – WINNER RUSH AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARD FOR BEST DIRECTION 12 YEARS A SLAVE Steve McQueen AMERICAN HUSTLE David O. Russell CAPTAIN PHILLIPS Paul Greengrass GRAVITY Alfonso Cuarón – WINNER THE GREAT GATSBY Baz Luhrmann AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARD FOR BEST SCREENPLAY 12 YEARS A SLAVE John Ridley AMERICAN HUSTLE Eric Warren Singer, David O. Russell – WINNER BLUE JASMINE Woody Allen INSIDE LLEWYN DAVIS Joel Coen, Ethan Coen SAVING MR. BANKS Kelly Marcel, Sue Smith AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARD FOR BEST LEAD ACTOR Christian Bale AMERICAN HUSTLE Leonardo DiCaprio THE WOLF OF WALL STREET Chiwetel Ejiofor 12 YEARS A SLAVE – WINNER Tom Hanks CAPTAIN PHILLIPS Matthew McConaughey DALLAS BUYERS CLUB AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARD FOR BEST LEAD ACTRESS Amy Adams AMERICAN HUSTLE Cate Blanchett BLUE JASMINE – WINNER Sandra Bullock GRAVITY Judi Dench PHILOMENA Meryl Streep AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARD FOR BEST SUPPORTING ACTOR Bradley Cooper AMERICAN HUSTLE Joel Edgerton THE GREAT GATSBY Michael Fassbender 12 YEARS A SLAVE – WINNER Jared Leto DALLAS BUYERS CLUB Geoffrey Rush THE BOOK THIEF Page 1 of 2 AACTA INTERNATIONAL AWARD FOR BEST SUPPORTING ACTRESS Sally Hawkins BLUE JASMINE Jennifer Lawrence AMERICAN HUSTLE – WINNER Lupita Nyong’o 12 YEARS A SLAVE Julia Roberts AUGUST: OSAGE COUNTY Octavia Spencer FRUITVALE STATION Page 2 of 2 . -

There's a Lot Going on in 'Australia': Baz Luhrmann's Claim to the Epic

10 • Metro Magazine 159 There’s a lot going on in Australia Baz Luhrmann’s Claim to the Epic Brian McFarlane REVIEWS BAZ LUHRmann’s EAGERLY AWAITED ‘Event’ FiLM. ou’ve got to admire the cheek of scape of a restricted kind. Does Luhrmann a director who calls his film simply believe that it is only Dorothea Mackellarland YAustralia. It implies that what is (all ‘sweeping plains’ and ‘ragged mountain going on in it is comprehensive enough, or ranges’ and ‘droughts and flooding rains’) at least symptomatic enough, to evoke the that the world at large will recognize as Aus- continent at large. Can it possibly live up to tralia? What he shows us is gorgeous be- such a grandiose announcement of intention? yond the shadow of a doubt – gorgeous, that There have been plenty of films named for is, to look at on a huge screen rather than to cities (New York, New York [Martin Scorsese, live in. It is, though, hardly the ‘Australia’ that 1977], Barcelona [Whit Stillman, 1994], most most of its inhabitants will know intimately, recently Paris [Cédric Klapisch, 2008]), but living as we do in our urban fastnesses, but summoning a city seems a modest enterprise the pictorial arts have done their bit in instill- compared with a country or a continent ing it as one of the sites of our yearning. (please sort us out, Senator Palin). D.W. Griffith in 1924 and Robert Downey Sr in Perhaps it’s really a love story at heart, a love 1986 had a go with America: neither director story in a huge setting that overpowers its is today remembered for his attempt to fragile forays into intimacy. -

Lexus Australian Short Film Fellowship

MEDIA RELEASE EMBARGOED UNTIL 6AM THURSDAY 24 MARCH SYDNEY FILM FESTIVAL ANNOUNCES 20 FINALISTS AND DISTINGUISHED JURY FOR LEXUS AUSTRALIAN SHORT FILM FELLOWSHIP The Sydney Film Festival and Lexus Australia today announced 21 filmmakers have been shortlisted by producers at The Weinstein Company, to compete for the largest cash fellowship for short film in Australia. Presiding over the selection process as Jury Chair is renowned Australian actress Judy Davis. The other jury members are Sydney Film Festival Director Nashen Moodley, Lexus Australia’s Adrian Weimers, and Australian producers Jan Chapman AO and Darren Dale. The industry luminaries will assess each finalist’s proposed short film projects to select up to four filmmakers, each of whom will receive a $50,000 Fellowship grant. The four successful candidates will be announced at the Sydney Film Festival (8-19 June 2016). The shortlisted filmmakers are: Alex Murawski (NSW) Dave Redman (VIC) Alex Ryan (NSW) David Hansen (VIC) Anya Beyersdorf (NSW) James Vinson (VIC) Billie Pleffer (NSW) Victoria Thaine (VIC) Brooke Goldfinch (NSW) Mikey Hill (VIC) Genevieve Clay-Smith (NSW) Thomas Baricevic (VIC) Hazel Annikki Savolainen (NSW) Erin Coates (WA) Jacobie Gray (NSW) Anna Nazzari (WA) Lucy Gaffy (NSW) Eddie White (SA) Tim Russell (NSW) Stephen de Villiers (SA) Venetia Taylor (NSW) The Weinstein Company chose 10 female and 11 male filmmakers from over 355 Australians who last year entered Lexus’s international short film competition, the Lexus Short Film Series. The Series was recently won by Australian actor and filmmaker Damian Walshe- Howling, alongside three other filmmakers from France, South Korea and the USA. -

Education Education Welcome Senior Cycle

Black Gold • Ten Canoes Comme une Image • Once Warchild • Los Olvidados Rocky Road to Dublin • Babel Mr Magorium’s Wonder Emporium Education BABEL Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu’s Autumn/Winter 2007 Welcome Senior Cycle IFI Education: Supporting film in school curricula and English promoting moving image culture for young audiences. We currently reach 20,000 students around Ireland at secondary and primary level with our extensive programme. This includes films in Irish, French, German and Spanish, alongside Leaving Cert English titles, new Irish films, documentaries and films for primary school audiences. Strictly Ballroom Oct 3, 10.30am Baz Luhrmann’s flamboyant and colourful debut film tells LAUNCH EVENT the story of Scott and Fran who struggle to dance their Cinema Paradiso – Original Version Sep 27, 10.30am own steps despite an authoritarian Dance Federation. We are delighted to launch this term’s events with two free screenings at the IFI: As You Like It This modern classic is showing for Leaving Cert 08 in the Told as a fairy tale, romantic comedy and dance musical original version. The story is revealed in flashback, when rolled into one, this is an excellent choice for comparative (for teachers) on September 19th at 6.30 pm, and A Mighty Heart (for students) on Salvatore (Toto) returns to the small Sicilian town of his child- study: accessible, fun and fast-paced, it also deals with September 20th at 10.30 am. hood for the funeral of his mentor, local projectionist Alfredo. more serious themes. FRANCE/ITALY • 1998 • COMEDY/DRAMA • 123 MIN AUS • 1992 • COMEDY/DRAMA • 94 MINS • DIR: BAZ LUHRMANN DIRECTOR: GUISEPPE TORNATORE ALSO SHOWING AT: Samhlaíocht Kerry Film Festival (Nov 5-9) Nov 5 Booking through Samhlaíocht on (066) 712 9934 Revision Workshops for Leaving Cert 2008 Hour-long workshop focussing on key moments for students of Leaving Cert 2008. -

THE GREAT GATSBY by Kristina Janeway Other Titles in This Series

Using the DOCUMENT-BASED QUESTIONS Technique for Literature: F. SCOTT FITZGERALD’S THE GREAT GATSBY by Kristina Janeway Other Titles in This Series Using the Document-Based Questions Technique for Literature: Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird Item Number 4B4971 Using the Document-Based Questions Technique for Literature: Arthur Miller’s The Crucible Item Number 4B4973 Using the Document-Based Questions Technique for Literature: Elie Wiesel’s Night Item Number 4B4972 Using the Document-Based Questions Technique for Literature: Lois Lowry’s The Giver Item Number 4B5905 Using the Document-Based Questions Technique for Literature: John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men Item Number 4B5926 Using the Document-Based Questions Technique for Literature: William Golding’s Lord of the Flies Item Number 4B5924 Using the Document-Based Questions Technique for Literature: George Orwell’s Animal Farm Item Number 4B5925 Using the Document-Based Questions Technique for Literature: George Orwell’s 1984 Item Number 4B6077 Using the Document-Based Questions Technique for Literature: Mark Twain’s Adventures of Huckleberry Finn Item Number 4B5906 Using the Document-Based Questions Technique for Literature: Ayn Rand’s Anthem Item Number 4B6224 Using the Document-Based Questions Technique for Literature: Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 Item Number 4B6167 Table of Contents About the Author ........................................................................................................................................................ 3 Correlation to Common Core -

Fitzgerald's Critique of the American Dream

Undergraduate Review Volume 7 Article 22 2011 God Bless America, Land of The onsC umer: Fitzgerald’s Critique of the American Dream Kimberly Pumphrey Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev Part of the American Literature Commons, and the Other American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Pumphrey, Kimberly (2011). God Bless America, Land of The onC sumer: Fitzgerald’s Critique of the American Dream. Undergraduate Review, 7, 115-120. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/undergrad_rev/vol7/iss1/22 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. Copyright © 2011 Kimberly Pumphrey God Bless America, Land of The Consumer: Fitzgerald’s Critique of the American Dream KIMBERLY PUMPHREY Kimberly is a senior n James Truslow Adams’ book, The Epic of America, he defines the studying English and American dream as “that dream of a land in which life should be better and richer and fuller for everyone, with opportunity for each according to ability Secondary Education. or achievement” (404). In the middle of the roaring 1920’s, author F. Scott This paper was IFitzgerald published The Great Gatsby, examining the fight for the American kindly mentored by dream in the lives of his characters in New York. Fitzgerald illustrates for the reader a picture of Gatsby’s struggle to obtain the approval and acceptance of high Professor Kimberly Chabot Davis society and to earn the same status. Jay Gatsby travels the journey to achieve the and was originally written for the American dream, but his dream is corrupted and outside forces prevent him from senior seminar course: Gender, Race, ever fully attaining it. -

Your Concert Guide

silver screen sounds your concert guide EDEN COURT caird hall tramway the queen's hall INVERNESS dundee glasgow edinburgh 10 Sep 14 Sep 15 Sep 16 Sep welcome to silver screen sounds Over the course of the concert, you'll hear music chosen to accompany films and extracts from scores written specifically for the screen. There'll be pauses between some, and others will flow into the next. We recommend following along with your listings insert, and using this guide as extra reading. 1 by Bernard Herrmann Prelude from Psycho psycho (1960) Directed by Alfred Hitchcock "When a director finds a composer who understands them, who can get inside their head, who can second-guess them correctly, they're just going to want to stick with that person. And Psycho... it was just one of these absolute instant connections of perfect union of music and image, and Hitchcock at his best, and Bernard Herrmann at his best." Film composer Danny Elfman Herrmann's now-equally-iconic soundtrack to Hitchcock's iconic film showed generations of filmmakers to come the power that music could have. It's a rare example of a film score composed for strings only, a restriction of tonal colour that was, according to an interview with Herrmann, intended as the musical equivalent of Hitchcock's choice of black and white (Hitchcock had originally requested a jazz score, as well as for the shower scene to be silent; Herrmann clearly decided he knew better). Also known as the 'Psycho theme', this prelude is frenetic and fast-paced, suggesting flight and pursuit. -

Literary Analysis: Color Symbolism in the Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald.” Helium 8 Nov

Yaffe, Kyle. “Literary analysis: Color symbolism in The Great Gatsby, by F. Scott Fitzgerald.” Helium 8 Nov. 2008. Web. 29 July 2013. Vibrant, deadly, deceiving, innocent - colors are the dominating symbols utilized by F. Scott Fitzgerald in his masterpiece The Great Gatsby . Daniel J. Schneider, the Chairman of the Department of English for Windham College, states, "The vitality and beauty of F. Scott Fitzgerald's writing are perhaps nowhere more strikingly exhibited than in his handling of the color symbols in The Great Gatsby." Throughout the book characters, places, and objects are given "life" by colors, especially the more prominent ones. The colors of white, yellow, and green are the most eminent, easily distinguishable from the rest, and representing purity, death, and hope. Such strong symbolic colors are seen continually, and exist to provide a higher and more in depth meaning to the book. "White is one of the main symbolic colors in The Great Gatsby, representing purity, innocence, and honesty" (Adam H.). Nick Carraway, Jay Gatsby, Jordan Baker, and Daisy Buchanan all directly exemplify Adam's statement. Nick considers himself the only truly honest person he knows (Fitzgerald 60) and often wears white, such as when he attends one of Gatsby's parties for the first time. This event being considerably significant, Nick wanted to make the best impression he could - that is, appearing untainted and honest - for Gatsby and the other guests. Gatsby also adorns himself in white when he finally reunites with Daisy after five years of separation. "and Gatsby, in a white flannel suit, silver shirt, and gold-colored tie, hurried in" (Fitzgerald 84). -

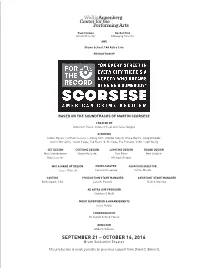

SEPTEMBER 21 – OCTOBER 16, 2016 Bram Goldsmith Theater CONNECT with US: This Production Is Made Possible by Generous Support from David C

THE WALLIS To find your happy Paul Crewes Rachel Fine & CODY LASSEN Artistic Director Managing Director PRODUCTION OF ending, go back to AND Shane Scheel / Ad Astra Live the beginning… PRODUCTION OF MUSIC AND LYRICS BY STEPHEN SONDHEIM BOOK BY GEORGE FURTH DIRECTED BY MICHAEL ARDEN BASED ON THE SOUNDTRACKS OF MARTIN SCORSESE CREATED BY Anderson Davis, Shane Scheel and Jesse Vargas STARRING James Byous, Carmen Cusack, Lindsey Gort, Dionne Gipson, Olivia Harris, Doug Kreeger, Justin Mortelliti, Jason Paige, Zak Resnick, B. Slade, Pia Toscano, John Lloyd Young SET DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN Matt Steinbrenner Steve Mazurek Dan Efros Ben Soldate Kyle Courter Michael Berger NOV 22 – DEC 18, 2016 WIG & MAKE UP DESIGN PROPS MASTER ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR Cassie Russek Carissa Huizenga Sumie Maeda CASTING PRODUCTION STAGE MANAGER ASSISTANT STAGE MANAGER Beth Lipari, CSA Lora K. Powell Rick V. Moreno AD ASTRA LIVE PRODUCER Siobhan O'Neill MUSIC SUPERVISION & ARRANGEMENTS Jesse Vargas CHOREOGRAPHY RJ Durell & Nick Florez DIRECTOR Anderson Davis SEPTEMBER 21 – OCTOBER 16, 2016 Bram Goldsmith Theater CONNECT WITH US: This production is made possible by generous support from David C. Bohnett. 310.746.4000 | TheWallis.org/Merrily Cast List About the Artists JAMES BYOUS DOUG KREEGER (Jake, Fight (IN ORDER OF APPEARANCE) (Travis) Collingwood. She has worked internationally in CAST When James Byous was in Australia with the revered and legendary director Captain) Broadway: Les Miserables second grade, his class put on a actress and producer, Debbie Allen, in her new (Broadhurst Theatre), The Visit JAMES BYOUS........................................................................................TRAVIS production of Stone Soup for musical Freeze Frame, as well as her nationally (Ambassador Theatre, Actors Fund ZAK RESNICK*.......................................................................................HENRY parents and friends. -

{PDF} Movies of the 2000S Kindle

MOVIES OF THE 2000S PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Taschen | 864 pages | 15 Feb 2012 | Taschen GmbH | 9783836501972 | English | Cologne, Germany Movies of the 2000s PDF Book AP Read the review. Iranian-French director Marjane Satrapi adapted her own graphic novel in this animated fantasy-memoir about a year-old girl growing up in Tehran after the revolution. The film won an Oscar for best adapted screenplay in But despite the wild variety among our 50 Best Movies from , each is an exquisitely made, exceptionally satisfying piece of cinema that we believe will endure well after the decade has ended. It would turn out to be his final film. Surprised by his talent, a teacher Julie Walters takes the boy under her wing but she and Billy face opposition from his family who forbid him from pursuing his dreams of dance. The film was lauded by critics and won Reese Witherspoon an Oscar for best actress. It was 10 years since Moon first premiered last year, which meant there were a lot of anniversary screenings at cinemas, opinion pieces about the film and a big resurgence for love of the movie on social media. Free subscriber-exclusive audiobook! When tragedy strikes, a group of women gather together to go on a spelunking adventure in the wilderness. Good luck watching this movie and not wanting to be a rockstar. In , of the film, The Guardian's Peter Bradshaw wrote: "The whole movie is a rich, spacious, passionate way of showing, not telling, feelings that dare not speak their name — and doing so with superb intelligence and magnificent candour. -

WINNERS Children’S Programs Documentary Daytime Serials

MARCH 2011 MICK JACKSON MARTINMARTIN SCORSCORSSESEESE MICHAEL SPILLER Movies For Television Dramatic Series Comedy Series and Mini-Series TOM HOOPER Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Feature Film GLENN WEISS EYTAN KELLER STACYSTACY WALLWALL Musical Variety Reality Programs Commercials ERIC BROSS CHARLES FERGUSON LARRY CARPENTER WINNERS Children’s Programs Documentary Daytime Serials In this Issue: • DGA 75th Anniversary events featuring Martin Scorsese, Kathryn Bigelow, Francis Ford Coppola and the game-changing VFX of TRON and TRON: Legacy • March Screenings, Meetings and Events MARCH MONTHLY VOLUME 8, NUMBER 3 Contents 1 29 MARCH MARCH CALENDAR: MEETINGS LOS ANGELES & SAN FRANCISCO 4 DGA NEWS 30-34 MEMBERSHIP 6-8 SCREENINGS UPCOMING EVENTS 35 RECENT 9-27 EVENTS DGA AWARDS COVERAGE 36 28 MEMBERSHIP MARCH CALENDAR: REPORT NEW YORK, CHICAGO, WASHINGTON, DC DGA COMMUNICATIONS DEPARTMENT Morgan Rumpf Assistant Executive Director, Communications Sahar Moridani Director of Media Relations Darrell L. Hope Editor, DGA Monthly & dga.org James Greenberg Editor, DGA Quarterly Tricia Noble Graphic Designer Jackie Lam Publications Associate Carley Johnson Administrative Assistant CONTACT INFORMATION 7920 Sunset Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90046-0907 www.dga.org (310) 289-2082 F: (310) 289-5384 E-mail: [email protected] PRINT PRODUCTION & ADVERTISING IngleDodd Publishing Dan Dodd - Advertising Director (310) 207-4410 ex. 236 E-mail: [email protected] DGA MONTHLY (USPS 24052) is published monthly by the Directors Guild of America, Inc., 7920 Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles, CA 90046-0907. Periodicals Postage paid at Los Angeles, CA 90052. SUBSCRIPTIONS: $6.00 of each Directors Guild of America member’s annual dues is allocated for an annual subscription to DGA MONTHLY. -

The Artist This February 'Love Is in the Air' in the Library. What Better Way To

This February ‘love is in the air’ in the library. What better way to enjoy Valentine’s Day than curled up on your couch watching a movie? From modern favourites to timeless classics, there are countless movies in the romance genre, so here at the Learning Curve we’re here to help you narrow them down. Get ready to laugh, cry, swoon, and everything in between with your favourite hunks, lovers, and heroines. Whether you're taking some ‘me time’ or cuddled up with that special someone, here at the library we have a great selection of DVDs. These can all be found on popular streaming services or borrowed from the library using our Click & Collect Service once lockdown is over. Be sure to have popcorn and tissues at the ready! The Artist Director: Michel Hazanavicius Actors: Jean Dujardin, Bérénice Bejo, John Goodman, James Cromwell, Penelope Ann Miller The Artist is a love letter and homage to classic black-and-white silent films. The film is enormously likable and is anchored by a charming performance from Jean Dujardin, as silent movie star George Valentin. In late-1920s Hollywood, as Valentin wonders if the arrival of talking pictures will cause him to fade into oblivion, he makes an intense connection with Peppy Miller, a young dancer set for a big break. As one career declines, another flourishes, and by channelling elements of A Star Is Born and Singing in the Rain, The Artist tells the engaging story with humour, melodrama, romance, and--most importantly--silence. As wonderful as the performances by Dujardin and Bérénice Bejo (Miller) are, the real star of The Artist is cinematographer Guillaume Schiffman.