Corporate Classicism and the Metaphysical Style EDITED

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BOSTON Is More Than a Running Film. It Is a Timeless Story About Triumph Over Adversity for Runner and Non-Runner Alike. Film Sy

BOSTON is more than a running film. It is a timeless story about triumph over adversity for runner and non-runner alike. Film Synopsis BOSTON is the first ever feature-length documentary film about the world’s most legendary run- ning race – the Boston Marathon. The film chronicles the story of the iconic race from its humble origins with only 15 runners to the present day. In addition to highlighting the event as the oldest annually contested marathon in the world, the film showcases many of the most important moments in more than a century of the race’s history. from a working man’s challenge welcoming foreign athletes and eventually women bec me the stage for manyThe Bostonfirsts and Marathon in no small evolved part the event that paved the way for the modern into a m world-classarathon and event, mass participatory sports. Following the tragic events of. The 2013, Boston BOSTON Marathon a the preparations and eventual running of the, 118th Boston Marathon one year later when runners and community gather once again for what will be the most meaningful raceshowcases of all. for , together The production was granted exclusive documentary rights from the Boston Athletic Association to produce the film and to use the Association’s extensive archive of video, photos and memorabilia. Production Credits: Boston is presented by John Hancock Financial, in association with the Kennedy/Marshall Com- pany. The film is directed by award winning filmmaker Jon Dunham, well known for his Spirit of the Marathon films, and produced by Academy Award-nominee Megan Williams and Eleanor Bingham Miller. -

B R I a N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N a L M U S I C I a N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R

B R I A N K I N G M U S I C I N D U S T R Y P R O F E S S I O N A L M U S I C I A N - C O M P O S E R - P R O D U C E R Brian’s profile encompasses a wide range of experience in music education and the entertainment industry; in music, BLUE WALL STUDIO - BKM | 1986 -PRESENT film, television, theater and radio. More than 300 live & recorded performances Diverse range of Artists & Musical Styles UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN CALIFORNIA Music for Media in NYC, Atlanta, L.A. & Paris For more information; www.bluewallstudio.com • As an administrator, professor and collaborator with USC working with many award-winning faculty and artists, PRODUCTION CREDITS - PARTIAL LIST including Michael Patterson, animation and digital arts, Medeski, Martin and Wood National Medal of Arts recipient, composer, Morton Johnny O’Neil Trio Lauridsen, celebrated filmmaker, founder of Lucasfilm and the subdudes (w/Bonnie Raitt) ILM, George Lucas, and his team at the Skywalker Ranch. The B- 52s Jerry Marotta Joseph Arthur • In music education, composition and sound, with a strong The Indigo Girls focus on establishing relations with industry professionals, R.E.M. including 13-time Oscar nominee, Thomas Newman, and 5- Alan Broadbent time nominee, Dennis Sands - relationships leading to PS Jonah internships in L.A. and fundraising projects with ASCAP, Caroline Aiken BMI, the RMALA and the Musician’s Union local 47. Kristen Hall Michelle Malone & Drag The River Melissa Manchester • In a leadership role, as program director, recruitment Jimmy Webb outcomes aligned with career success for graduates Col. -

PASIC 2010 Program

201 PASIC November 10–13 • Indianapolis, IN PROGRAM PAS President’s Welcome 4 Special Thanks 6 Area Map and Restaurant Guide 8 Convention Center Map 10 Exhibitors by Name 12 Exhibit Hall Map 13 Exhibitors by Category 14 Exhibitor Company Descriptions 18 Artist Sponsors 34 Wednesday, November 10 Schedule of Events 42 Thursday, November 11 Schedule of Events 44 Friday, November 12 Schedule of Events 48 Saturday, November 13 Schedule of Events 52 Artists and Clinicians Bios 56 History of the Percussive Arts Society 90 PAS 2010 Awards 94 PASIC 2010 Advertisers 96 PAS President’s Welcome elcome 2010). On Friday (November 12, 2010) at Ten Drum Art Percussion Group from Wback to 1 P.M., Richard Cooke will lead a presen- Taiwan. This short presentation cer- Indianapolis tation on the acquisition and restora- emony provides us with an opportu- and our 35th tion of “Old Granddad,” Lou Harrison’s nity to honor and appreciate the hard Percussive unique gamelan that will include a short working people in our Society. Arts Society performance of this remarkable instru- This year’s PAS Hall of Fame recipi- International ment now on display in the plaza. Then, ents, Stanley Leonard, Walter Rosen- Convention! on Saturday (November 13, 2010) at berger and Jack DeJohnette will be We can now 1 P.M., PAS Historian James Strain will inducted on Friday evening at our Hall call Indy our home as we have dig into the PAS instrument collection of Fame Celebration. How exciting to settled nicely into our museum, office and showcase several rare and special add these great musicians to our very and convention space. -

Jump Point 06.04 – Scoring

FROM THE COCKPIT IN THIS ISSUE >>> 03 BEHIND THE SCREENS : Composers 19 WORK IN PROGRESS : Origin 100 Series 35 WHITLEY’S GUIDE : 300i 39 WHERE IN THE ‘VERSE? ISSUE: 06 04 40 ONE QUESTION PART 2: What was the first game & system you played? Editor: David Ladyman Roving Correspondent: Ben Lesnick Layout: Michael Alder FROM THE COCKPIT GREETINGS, CITIZENS! As promised last month, we deliver the parts we a couple weeks ago. I am boggled by the number of couldn’t fit in the March issue. We have interviews zeros that entails, and I can do no better than quote with the two primary composers for Squadron 42 Chris in saying, “It’s your belief in the project, from the and SC Persistent Universe music (Geoff Zanelli and earliest backers to those relatively new to the ’verse, Pedro Camacho, respectively) — basically Part 4 of that make it all possible.” our three-part Audio Behind the Screens discussions. The body of previous work for each of these We also hit Alpha 3.1 on schedule, with plenty of composers is stellar, and it appears that they are expanded role-playing features (including a character going above and beyond with CIG’s soundtracks. customizer and service beacons), with a dozen new personal weapons, and with five new flyable (or We also have the second half of the CIG staff responses driveable) craft: the Cyclone, Reclaimer, Terrapin, to our One Question, for your reading pleasure: What Razor and Kue. Your enthusiasm is so important in was the first electronic or computer game you can fueling the drive of everyone at Cloud Imperium remember playing, and on what system? Games to continue creating and innovating in ways that others can only dream of. -

GAVIN GREGORY VFX Producer

GAVIN GREGORY VFX Producer PROJECTS DIRECTORS STUDIOS/PRODUCERS LAST NIGHT IN SOHO Edgar Wright FOCUS / WORKING TITLE Feature Film Eric Fellner, Tim Bevan, Nira Park VFX Producer Official Selection – TIFF HALF BAD Colm McCarthy THE IMAGINARIUM / NETFLIX Season 1 Joe Barton, Adrian Sturges VFX Producer Andy Serkis, Jonathan Cavendish Will Tennant, Steve Clarke-Hall THE SECRET GARDEN Marc Munden STX FILMS Feature Film David Heyman, Rosie Alison VFX Producer Jane Robertson ROBIN HOOD Otto Bathurst LIONSGATE / SUMMIT ENT. Feature Film Howard Ellis, Adam Goodman VFX Producer – Cinesite Jennifer Davisson, David James Kelly AVENGERS: INFINITY WARS Anthony Russo DISNEY / MARVEL Feature Film Joe Russo Kevin Feige, Mitchell Bell Executive Production Support – Cinesite EMERAL CITY Tarsem Singh NBC Season 1 Matthew Arnold, Shaun Cassidy VFX Producer – Freefolk David Schulner, Peter Welter Soler DA VINCI’S DEMONS Various Directors BBC / STARZ Seasons 2 & 3 David Goyer, Matthew Bouch VFX Producer – Realise Amy Berg, John Shiban BLACK SAILS Neil Marshall STARZ Season 1 – 2 episodes T.J. Scott Michael Bay, Brad Fuller VFX Producer Jonathan Steinberg Winner, Outstanding Special & Visual Effects – Emmys KINGSMAN: THE SECRET SERVICE Matthew Vaughn 20TH CENTURY FOX Feature Film Henry Jackman, Matthew Margeson Visual Effects Producer (Development) – For Realise ENDER’S GAME Gavin Hood LIONSGATE / SUMMIT ENT. Feature Film Alex Kurtzman, Roberto Orci Visual Effects Producer– Reliance / Digital Gigi Pritzker, Lynn Hendee Domain Robert Chartoff, Orson Scott Card FLYING MONSTERS 3D WITH Matthew Dyas ATLANTIC PRODUCTIONS DAVID ATTENBOROUGH Sias Wilson Documentary Visual Effects Producer Winner, Best Specialist Factual – BAFTA IRONCLAD Jonathan English ARC ENTERTAINMENT Feature Film Rick Benattar, Andrew J Curtis Visual Effects Producer – Molinaire HARRY POTTER AND THE DEATHLY David Yates WARNER BROS. -

Knowledge Organiser

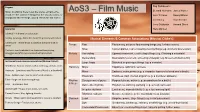

Key Composers Purpose Bernard Hermann James Horner Music in a film is there to set the scene, enhance the AoS3 – Film Music mood, tell the audience things that the visuals cannot, or John Williams Danny Elfman manipulate their feelings. Sound effects are not music! John Barry Alan Silvestri Jerry Goldsmith Howard Shore Key terms Hans Zimmer Leitmotif – A theme for a character Mickey-mousing – When the music fits precisely with action Musical Elements & Common Associations (Musical Cliche’s) Underscore – where music is played at the same time as action Tempo Fast Excitement, action or fast-moving things (eg. A chase scene) Slow Contemplation, rest or slowing-moving things (eg. A funeral procession) Fanfare – short melodies from brass sections playing arpeggios and often accompanied with percussion Melody Ascending Upward movement, or a feeling of hope (eg. Climbing a mountain) Descending Downward movement, or feeling of despair (eg. Movement down a hill) Instruments and common associations (Musical Clichés) Large leaps Distorted or grotesque things (eg. a monster) Woodwind - Natural sounds such as bird song, animals, rivers Harmony Major Happiness, optimism, success Bassoons – Sometimes used for comic effect (i.e. a drunkard) Minor Sadness, seriousness (e.g. a character learns of a loved one’s death) Brass - Soldiers, war, royalty, ceremonial occasions Dissonant Scariness, pain, mental anguish (e.g. a murderer appears) Tuba – Large and slow moving things Rhythm Strong sense of pulse Purposefulness, action (e.g. preparations for a battle) & Metre Harp – Tenderness, love Dance-like rhythms Playfulness, dancing, partying (e.g. a medieval feast) Glockenspiel – Magic, music boxes, fairy tales Irregular rhythms Excitement, unpredictability (e.g. -

The Pirates of the Caribbean

Music composed by Klaus Badelt and Hans Zimmer - arranged by Steven Verhaert The Pirates of The Caribbean For Brass Quintet Including the main themes "The Medallion Calls" , "The Black Pearl" and "He's A Pirate" from Walt Disney's "Pirates of the Caribbean" Allegro moderato q= 110 ° j > #3 ∑ ∑ Œ -œ 1st Trumpet in Bb & 4 œ œ œ™ -œ -œ œ œ >- >- >- > > >- >- #3 mf 2nd Trumpet in Bb & 4 ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ 3 Horn in F & 4 œ œœœ œ œ œ œ œœœ œ œ œ œ œœœ œ œ œ œ œœœ œœœ œ œ œœœ œœœ œ > >- > mf > > >-œ™ -œ œ -œ >- >-œ ? 3 -œ -œ J œ Trombone b4 ∑ ∑ Œ mf ? 3 ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ ‰ Œ ‰ Œ Tuba ¢ b4 j j j j j j j j j j j œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ mf 6 ° # >- >-™ j j & œ -œ œ -œ™ ‰ œ -œ œ -œ œ œ œ œ ™ œ ‰ j j‰ >- > > >- > > >- >- >- >- -œ >- -œ œ. œ. œ. œ. œ > > > >. # & ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ ∑ & œ œœœ œœœ œ j‰ Œ j ‰ j ‰ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œœœ œ œ œ œ œ™ œ œ œ œ œ j - >- -œ . œ. >- >-™ >-™ >- >- > >- > > > > >- >-œ œ œ >- >-œ œ œ œ #-œ œ >-œ >-™ n>-œ >- > ? œ œ J œ J œ œ. œ. œ. j j b ‰ ‰ œ œ ‰ >. ? j‰ Œ ‰ Œ j‰ ‰ ¢ b œ œ œ j œ œœœ œ œ œœœ œœ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ œ The Medallion Calls (from The Pirates of The Caribbean) Words and Music by Klaus Badelt, Hans Zimmer and Ramin Djawadi © 2004 Walt Disney Music (USA) Co, USA administered by Artemis Muziekuitgeverij B.V., The Netherlands This arrangement © 2014 Walt Disney Music (USA) Co, USA administered by Artemis Muziekuitgeverij B.V., The Netherlands Warner/Chappell Artemis Music Ltd, London W8 5DA Reproduced by permission of Faber Music Ltd All Rights Reserved. -

68Th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS for Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016

EMBARGOED UNTIL 8:40AM PT ON JULY 14, 2016 68th EMMY® AWARDS NOMINATIONS For Programs Airing June 1, 2015 – May 31, 2016 Los Angeles, CA, July 14, 2016– Nominations for the 68th Emmy® Awards were announced today by the Television Academy in a ceremony hosted by Television Academy Chairman and CEO Bruce Rosenblum along with Anthony Anderson from the ABC series black-ish and Lauren Graham from Parenthood and the upcoming Netflix revival, Gilmore Girls. "Television dominates the entertainment conversation and is enjoying the most spectacular run in its history with breakthrough creativity, emerging platforms and dynamic new opportunities for our industry's storytellers," said Rosenblum. “From favorites like Game of Thrones, Veep, and House of Cards to nominations newcomers like black-ish, Master of None, The Americans and Mr. Robot, television has never been more impactful in its storytelling, sheer breadth of series and quality of performances by an incredibly diverse array of talented performers. “The Television Academy is thrilled to once again honor the very best that television has to offer.” This year’s Drama and Comedy Series nominees include first-timers as well as returning programs to the Emmy competition: black-ish and Master of None are new in the Outstanding Comedy Series category, and Mr. Robot and The Americans in the Outstanding Drama Series competition. Additionally, both Veep and Game of Thrones return to vie for their second Emmy in Outstanding Comedy Series and Outstanding Drama Series respectively. While Game of Thrones again tallied the most nominations (23), limited series The People v. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story and Fargo received 22 nominations and 18 nominations respectively. -

1 Filmová Hudba 1. 1 Definice Filmové Hudby

Univerzita Palackého v Olomouci Pedagogická fakulta Katedra hudební výchovy Bakalá řská práce Veronika Lyková Obor: Spole čenské v ědy se zam ěř ením na vzd ělávání a hudební kultura se zam ěř ením na vzd ělávání Hudba ve fantasy filmech Vedoucí práce: MgA. Petr Martínek Olomouc 2017 Prohlašuji, že jsem svou bakalá řskou práci zpracovala samostatn ě a že jsem uvedla veškerou literaturu a zdroje, které jsem k práci využila. V Olomouci dne 17. 6. 2017 …..…..…..…………………. Podpis Děkuji vedoucímu své bakalá řské práce, panu MgA. Petru Martínkovi, za trp ělivost a ochotu. Dále bych ráda pod ěkovala paní Mgr. Gabriele Všeti čkové, Ph.D., za poskytnuté rady, a panu Mgr. Filipu T. Krej čímu, Ph.D., za doporu čenou literaturu. Obsah Úvod .................................................................................................................................. 7 1 Historie filmové hudby .................................................................................................. 9 1. 1 Definice filmové hudby......................................................................................... 9 1. 2 Historie filmové hudby ......................................................................................... 9 1. 3 Tvorba filmové hudby ......................................................................................... 10 2 Howard Shore .............................................................................................................. 12 2. 1 Pán prsten ů ......................................................................................................... -

Neuerwerbungen Noten

NEUERWERBUNGSLISTE OKTOBER 2019 FILM Cinemathek in der Amerika-Gedenkbibliothek © Eva Kietzmann, ZLB Zentral- und Landesbibliothek Berlin Stiftung des öffentlichen Rechts Inhaltsverzeichnis Film 5 Stummfilme 3 Film 7 Fernsehserien 3 Film 10 Tonspielfilme 6 Film 20 Animationsfilme 24 Film 27 Animation/Anime Serien 24 Film 30 Experimentalfilme 24 Film 40 Dokumentarfilme 25 Musi Musikdarbietungen/ Musikvideos 25 K 400 Kinderfilme 26 Ju 400 Jugendfilme 38 Sachfilme nach Fachgebiet 42 Seite 2 von 48 Stand vom: 01.11.2019 Neuerwerbungen im Fachbereich Film Film 5 Stummfilme Film 5 Chap 1 ¬The¬ circus / Charles Chaplin [Regie Drehbuch Darst. Prod. a:BD Komp.]. Merna Kennedy [Darst.] ; Allan Garcia [Darst.] ; Harry Cro- cker [Darst.] ; Eric James [Musikberatung] ; Lambert Williamson [Musikarrangement] ; Charles D. Hall [Ausstattung]. - 2019 Film 5 Chap 1 ¬The¬ circus / Charles Chaplin [Regie Drehbuch Darst. Prod. c:DVD Komp.]. Merna Kennedy [Darst.] ; Allan Garcia [Darst.] ; Harry Cro- cker [Darst.] ; Eric James [Musikberatung] ; Lambert Williamson [Musikarrangement] ; Charles D. Hall [Ausstattung]. - 2019 Film 7 Fernsehserien Film 7 AgentsS Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. : [BD]. - 4. Staffel. ¬Die¬ komplette vierte 1:4.BD Staffel / Filmregisseur: Vincent Misiano ; Drehbuchautor: Stan Lee ; Komponist: Bear McCreary ; Kameramann: Feliks Parnell ; Schau- spieler: Clark Gregg, Ming-Na Wen ; Chloe Bennet, Iain de Caeste- cker [und weitere]. - 2019 Film 7 AgentsS 1 Agents of S.H.I.E.L.D. : [DVD-Video]. - 4. Staffel, Episoden 1-22. a:4.DVD ¬Die¬ komplette vierte Staffel. - 2019 Film 7 AmerHor American Horror Story : [BD]. - 8. Staffel. Apocalypse : die kom- 1:8.BD plette achte Season / Filmregisseur: Bradley Buecker ; Drehbuch- autor: Brad Falchuk, Ryan Murphy ; Komponist: James S. -

Alan Silvestri

ALAN SILVESTRI AWARDS/NOMINATIONS EMMY NOMINATION (2014) COSMOS: A SPACETIME ODYSSEY Outstanding Music Composition for a Series / Original Dramatic Score and Outstanding Original Main Title Music WORLD SOUNDTRACK NOMINATION (2008) “A Hero Comes Home” from BEOWULF Best Original Song Written for Film* INTERNATIONAL FILM MUSIC CRITICS BEOWULF ASSOCIATION NOMINATION (2007) Best Original Score-Animated Feature GRAMMY AWARD (20 05) “Believe” from THE POLAR EXPRESS Best Song Written for a Motion Picture* ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (2005) “Believe” from THE POLAR EXPRESS Best Original Song* GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (2005) “Believe” from THE POLAR EXPRESS Best Original Song* BRO ADCAST FILM CRITICS CHOICE “Believe” from THE POLAR EXPRESS NOMINATION (2004) Best Song* GRAMMY AWARD (2001) End Credits from CAST AWAY Best Instrumental Composition ACADEMY AWARD NOMINATION (1994) FORREST GUMP Best Original Score GRAMMY AWARD NOMINA TION (1994) “Feather” from FORREST GUMP Best Instrumental Performance GOLDEN GLOBE NOMINATION (1994) FORREST GUMP Best Original Score CABLE ACE AWARD (1990) TALES FROM THE CRYPT: ALL THROUGH Best Original Score THE HOUSE GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1989) Suite from WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT? Best Instrumental Composition GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1988) WHO FRAMED ROGER RABBIT? Best Album of Original Score Written for a Motion Picture GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1985) BA CK TO THE FUTURE Best Instrumental Composition 1 The Gorfaine/Schwartz Agency (818) 260-8500 ALAN SILVESTRI GRAMMY AWARD NOMINATION (1985) BACK TO THE FUTURE Best Album of Original Score Written for a Motion Picture *shared nomination/award MOTION PICTURES RUN ALL NIGHT Roy Lee / Michael Tadross / Brooklyn Weaver, prods. Warner Brothers Jaume Collet-Serra, dir. RED 2 Lorenzo di Bonaventura / Mark Vahradian, prods. -

Aesthetics of the Motion Picture Soundtrack Columbia College, Chicago Spring 2014 – Section 01 – Pantelis N

Aesthetics of the Motion Picture Soundtrack Columbia College, Chicago Spring 2014 – Section 01 – Pantelis N. Vassilakis Ph.D. http://lms.colum.edu Course # / Section 43-2410 / 01 Credits 3 hours Class time / place Thursday 12:30 – 3:20 p.m. 33 E. Congress Ave., Room LL18 (Lower Level – Control Room C) Course Site On MOODLE http://lms.colum.edu Instructor Pantelis N. Vassilakis, Ph.D. Phone Office: 312-369-8821 – Cell: 773-750-4874 e-mail / web [email protected] / http://www.acousticslab.org Office hours By appointment; Preferred mode of Communication: email Pre-requisites 52-1152 “Writing and Rhetoric II” (C or better) AND 43-2420 “Audio for Visual Media I” OR 24-2101 “Post Production Audio I” OR 43-2310 “Psychoacoustics” INTRODUCTION During the filming of Lifeboat, composer David Raksin was told that Hitchcock had decided against using any music. Since the action took place in a boat on the open sea, where would the music come from? Raksin reportedly responded by asking Hitchcock where the cameras came from. This course examines film sound practices, focusing on cross-modal perception and cognition: on ways in which sounds influence what we “see” and images influence what we “hear.” Classes are conducted in a lecture format and involve multimedia demonstrations. We will be tackling the following questions: • How and why does music and sound effects work in films? • How did they come to be paired with the motion picture? • How did film sound conventions develop and what are their theoretical, socio-cultural, and cognitive bases? • How does non-speech sound contribute to a film’s narrative and how can such contribution be creatively explored? Aesthetics of the Motion Picture Soundtrack – Spring 2014 – Section 01 Page 1 of 12 COURSE DESCRIPTION & OBJECTIVES Course examines Classical Hollywood as well as more recent film soundtrack practices, focusing on the interpretation of film sound relative to ‘expectancy’ theories of meaning and emotion.