The Role of Architecture in Transforming the Public

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

IAUP Baku 2018 Semi-Annual Meeting

IAUP Baku 2018 Semi-Annual Meeting “Globalization and New Dimensions in Higher Education” 18-20th April, 2018 Venue: Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers Website: https://iaupasoiu.meetinghand.com/en/#home CONFERENCE PROGRAMME WEDNESDAY 18th April 2018 Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers 18:30 Registration 1A, Mehdi Hüseyn Street Fairmont Baku, Flame Towers, 19:00-21:00 Opening Cocktail Party Uzeyir Hajibeyov Ballroom, 19:05 Welcome speech by IAUP President Mr. Kakha Shengelia 19:10 Welcome speech by Ministry of Education representative 19:30 Opening Speech by Rector of ASOIU Mustafa Babanli THURSDAY 19th April 2018 Visit to Alley of Honor, Martyrs' Lane Meeting Point: Foyer in Fairmont 09:00 - 09:45 Hotel 10:00 - 10:15 Mr. Kakha Shengelia Nizami Ganjavi A Grand Ballroom, IAUP President Fairmont Baku 10:15 - 10:30 Mr. Ceyhun Bayramov Deputy Minister of Education of the Republic of Azerbaijan 10:30-10:45 Mr. Mikheil Chkhenkeli Minister of Education and Science of Georgia 10:45 - 11:00 Prof. Mustafa Babanli Rector of Azerbaijan State Oil and Industry University 11:00 - 11:30 Coffee Break Keynote 1: Modern approach to knowledge transfer: interdisciplinary 11:30 - 12:00 studies and creative thinking Speaker: Prof. Philippe Turek University of Strasbourg 12:00 - 13:00 Panel discussion 1 13:00 - 14:00 Lunch 14:00 - 15:30 Networking meeting of rectors and presidents 14:00– 16:00 Floor Presentation of Azerbaijani Universities (parallel to the networking meeting) 18:30 - 19:00 Transfer from Farimont Hotel to Buta Palace Small Hall, Buta Palace 19:00 - 22:00 Gala -

The City of Winds

Travel by Nivine Maktabi Baku the City of Winds Heyder Aliyev Center designed by Zaha Hadid. Should I call it the City of Caviar, Oil and Gaz or the land of Caucasian Carpets? It was in May, right after Beirut Designers’ Week, when I packed a small suitcase and I am specifying small as I admit it was a big mistake to try and travel light for a change. I was flying to Baku, capital of Azerbaijan, a city which name’s always fascinated me. In fact, for me, Azerbaijan, the home of the Caucasus, is a name I only crossed in my readings Oil tanks in the middle of the sea. and specially when researching on Caucasian carpets. I headed to Fairmont Hotel, known as the Flame towers, the tallest and biggest three skyscrapers in the city. An impressive archi- 4 am was the take off; of course I was sleepy and slept on both tecture overlooking the city and the Caspian Sea was awaiting me. connecting flights, from Beirut to Istanbul and Istanbul to Baku. As it is not yet a popular touristic destination, most passengers Due to my several travels to carpet manufacturing countries, were either locals or Turkish and around one or two foreigners Azerbaijan was actually a big surprise, very different from what I I would assume working for a petroleum company, BT or alike. imagined it. While still in the taxi, at some point I thought I was in Dubai, then some of the buildings and highways reminded me of Upon arrival, the sun was blinding and a line of black cabs were filling St Petersburg and then again the boulevards resembled Paris. -

Azerbaijan Investment Guide 2015

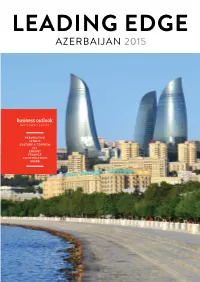

PERSPECTIVE SPORTS CULTURE & TOURISM ICT ENERGY FINANCE CONSTRUCTION GUIDE Contents 4 24 92 HE Ilham Aliyev Sports Energy HE Ilham Aliyev, President Find out how Azerbaijan is The Caspian powerhouse is of Azerbaijan talks about the entering the world of global entering stage two of its oil future for Azerbaijan’s econ- sporting events to improve and gas development plans, omy, its sporting develop- its international image, and with eyes firmly on the ment and cultural tolerance. boost tourism. European market. 8 50 120 Perspective Culture & Finance Tourism What is modern Azerbaijan? Diversifying the sector MICE tourism, economic Discover Azerbaijan’s is key for the country’s diversification, international hospitality, art, music, and development, see how relations and building for tolerance for other cultures PASHA Holdings are at the future. both in the capital Baku the forefront of this move. and beyond. 128 76 Construction ICT Building the monuments Rapid development of the that will come to define sector will see Azerbaijan Azerbaijan’s past, present and future in all its glory. ASSOCIATE PUBLISHERS: become one of the regional Nicole HOWARTH, leaders in this vital area of JOHN Maratheftis the economy. EDITOR: 138 BENJAMIN HEWISON Guide ART DIRECTOR: JESSICA DORIA All you need to know about Baku and beyond in one PROJECT DIRECTOR: PHIL SMITH place. Venture forth and explore the ‘Land of Fire’. PROJECT COORDINATOR: ANNA KOERNER CONTRIBUTING WRITERS: MARK Elliott, CARMEN Valache, NIGAR Orujova COVER IMAGE: © RAMIL ALIYEV / shutterstock.com 2nd floor, Berkeley Square House London W1J 6BD, United Kingdom In partnership with T: +44207 887 6105 E: [email protected] LEADING EDGE AZERBAIJAN 2015 5 Interview between Leading Edge and His Excellency Ilham Aliyev, President of the Republic of Azerbaijan LE: Your Excellency, in October 2013 you received strong reserves that amount to over US $53 billion, which is a very support from the people of Azerbaijan and were re-elect- favourable figure when compared to the rest of the world. -

Baku's Flame Towers

www.private-air-mag.com 1 DEPARTURES Like a Phoenix: Baku’s FLAME TOWERS By: Joseph Reaney ou can see why Baku is often iconic landmark. Located at the city’s iconic shape work as a building began.” called ‘the new Dubai’. It is a city highest point and climbing even higher permanently under construction, into the sky, it is always visible from Impressive as they are by day, the towers where the vast majority of city highlights almost anywhere in Baku. take on an entirely new dimension by Yhave been created in the 21st century night. That is because they feature the and even time-honored attractions, Designed by renowned architects HOK, world’s largest media facade application; like the city’s Old Town, have been so the flame columns were a big challenge. customer-designed strips of LEDs above extensively renovated they almost feel HOK’s Head of Mixed Use, Barry each window that, when lit together, like fresh additions. This spirit of newness Hughes says: “The real constraint was appear to illuminate the whole structure. is best seen in the capital’s landmark to stay true to the flame tower concept. As each strip is independently controlled, architectural achievement, the Flame The idea of the flame resonated with the the building can project a variety of Towers; three gigantic flame-shaped client because it had a direct connection images and patterns; the most famous of columns standing high above the city. with the history of the region, and which is a flickering red flame. And one of these towers is home to Azerbaijan’s tagline, ‘The Land of the Baku’s finest hotel. -

Presentation Scrolable Compressed

Welcome to Baku, Azerbaijan Country is the part of Silk Road, situated at the crossroads of Southwest Asia and Southeastern Europe. Land Area: 82,629 km2 Water Area: 3,971 km2 Total Area: 86,600km2 (#111) World Heritage Sites in Azerbaijan ATESHGAH FIRE TEMPLE (6th c.) State Historical Architectural Reserve Burning natural gas outlets Ancient Persian Temple for re worshipers ICHERISHEHER (Old City) Maiden Tower, Karvan Saray Ukhara, Karvan Saray Multani Baku Khan's Residence Shirvan Shahs' Palace, Aga-Mikhail bath house Double Gates, Old Mosques GOBUSTAN 6,000 Rock engraving Dated between 5,000 and 40,000 years ago. Caves, Settlements, Mud Volcanoes Baku Multicultural City MUSEUMS AND CULTURE CENTERS: Heydar Aliyev Cultural Centre Museum of Azerbaijan History Mugam Centre Carpet Museum Opera and Ballet Theater Museum of Modern Art CITY SIGHTS: Flame Towers Crystal Hall Flag Square Baku Eye Baku Boulevard ENTERTAINMENT: Art Galleries, IMAX cinema National and International Restaurants/Cafes/Bars SHOPPING: Port Baku Mall, Ganjlik Mall 28 Mall, Park Bulvar Mall Neftchilar Avenue, Metropark Mall Azerbaijani Cuisine MEAT: Kebab, Dolma, Levengi, Gutab, Piti FISH: Sturgeon, Black Caviar, Trout SOUPS: Doushbara, Dovgha, Bozbash PLOV: 40 Different types VEGETERIAN: Kuku (egg), Gutab (greens) Pumpkin rice, vegetable kebab SWEETS: Shekerbura, Pakhlava, Sheker Chorek FRUITS: Pomegranate, Persimmon Flame Towers • FAIRMONT BAKU brings 299 guest rooms, suites and 19 serviced apartments including Fairmont Gold • BUSINESS TOWER with 35 000 m2 working -

1 Conclusions of the 33Rd Meeting of the ICAPP Standing Committee

Conclusions of the 33rd Meeting of the ICAPP Standing Committee (Terengganu, Malaysia, 13 December 2019) The 33rd Meeting (hereinafter referred to as “the Meeting”) of the Standing Committee (hereinafter referred to as “the SC”) of the International Conference of Asian Political Parties (hereinafter referred to as “the ICAPP”) was held in Rajawali 2 Hall of Duyong Marina & Resort Terengganu in Terengganu, Malaysia from 21:30 to 22:30 on 13 December 2019 back- to-back with and prior to the 1st Meeting of the ICAPP Tourism Promotion and Inter-City Cooperation (TOPIC) Council. 20 Members attended the SC Meeting which was held prior to the First Meeting of the TOPIC Council held in Terengganu, Malaysia on 13-16 December 2019, co-hosted by the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), Parti Islam Se-Malaysia (PAS), and the State of Terengganu. The List of Participants and Annotated Agenda are attached as Appendixes I-1 and I-2. The Meeting was co-chaired by Hon. Mushahid Hussain Sayed, Vice-Chairman and Special Rapporteur of ICAPP Standing Committee, Senator and Chairman of Senate Committee on Foreign Affairs of the Pakistan Muslim League-N and Hon. Park Ro-byug, Secretary General of the ICAPP. Furthermore, Hon. Dato’ Seri Dr. Shahidan Bin Kassim attended as Chairperson of the Organizing Committee of the 1st Meeting of the TOPIC Council. Hon. Mushahid Hussain Sayed extended his warm welcome to all the SC Members, also expressing his deep gratitude for the hospitality from the host of the 1st Meeting of the TOPIC Council on behalf of Hon. Jose de Venecia, Jr., Founding Chairman and Chairman of the ICAPP SC. -

Azerbaijan: the Repression Games

AZERBAIJAN: THE REPRESSION GAMES THE VOICES YOU WON’T HEAR AT THE FIRST EUROPEAN GAMES 1 The first ever European Games are due to take place in (Above) Flame Towers in downtown Baku, the capital of Azerbaijan, on 12-28 June 2015. This Baku © Amnesty International multi-sport event will involve around 6,000 athletes and features a new state-of-the-art stadium costing some US$640 million. The games will give a huge boost to the government’s campaign to portray Azerbaijan as a progressive and politically stable rising economic Key Country Facts power. According to the President of Azerbaijan, Ilham Aliyev, the hosting of the European Games ‘will enable Azerbaijan to assert itself again Head of State throughout Europe as a strong, growing and a modern state.’2 President Ilham Aliyev But behind the image trumpeted by the government of a forward-looking, Head of Government modern nation is a state where criticism of the authorities is routinely Artur Rasizadze and increasingly met with repression. Journalists, political activists and human rights defenders who dare to challenge the government face Population trumped up charges, unfair trials and lengthy prison sentences. 9,583,200 In recent years, the Azerbaijani authorities have mounted an Area unprecedented clampdown on independent voices within the country. 86,600 km2 They have done so quietly and incrementally with the result that their actions have largely escaped consequences. The effects, however, are unmistakable. When Amnesty International visited the country in March 2015, there was almost no evidence of independent civil society activities and dissenting voices have been effectively muzzled. -

2013-Azetouri-043

MINISTRY OF CULTURE AND TOURISM OF THE REPUBLIC OF AZERBAIJAN PROJECT No.2013-AZETOURI-043 “CITIES OF COMMON CULTURAL HERITAGE” SCIENTIFIC-RESEARCH REPORT PROJECT MANAGER AYDIN ISMIYEV RESEARCHERS DR. FARIZ KHALILLI TARLAN GULIYEV 1 BAKU - 2014 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ABOUT THE “CITIES OF COMMON CULTURAL HERITAGE” PROJECT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. TURKEY 1.1. Van 1.2. Ahlat 1.3. Erzurum 1.4. Amasya 2. AZERBAIJAN 2.1. Ganja 2.2. Shamkir 2.3. Gabala 2.4. Shamakhi 2.5. Aghsu 3. KAZAKHSTAN 3.1. Esik 3.2. Tamgali 3.3. Taraz 3.4. Turkistan 3.5. Otrar 4. UZBEKISTAN 4.1. Samarkand 4.3. Shahrisabz 4.4. Termez 4.5. Bukhara 4.6. Khiva CONCLUSION RECOMMENDATIONS ANNEX 1. Accomodation establishments ANNEX 2. Travel agencies ANNEX 3. Tour program 1 ANNEX 4. Tour program 2 ANNEX 5. Template Questionnaire ANNEX 6. Questionnaire results REFERENCES PHOTOS 2 INTRODUCTION Archaeological tourism is a new field within cultural tourism that has developed as a result of people’s interest in the past. Archaeological tourism consists of two main activities: visits to archaeological excavation sites and participation in the studies undertaken there. The target group of archaeological tourism includes intellectuals and various people having an interest in archaeology. Any politician, bank employee, doctor, artist or other professional or working person can now spend their vacation at the archaeological excavation site of which they’ve dreamed. The development of this tourism focus area presents a novel product to the tourism economy and increases innovation in archaeology. Three main paths must be followed in order to successfully offer an archaeological tourism product: research, conservation and promotion. -

04 Nights Baku

PLAISIR HOSPITALITY SERVICES Program: 04 Nights Baku Day 1 – Arrival to Baku Upon arrival to International airport of Baku the tourist will be met by our representative.After meeting we will transfer to the hotel. Upon arrival to the hotel we will have check in to the hotel and have a free time. Overnight in Baku. Day 2 – Baku City Tour and Ateshgah Temple Tour Start exploring Baku. Panorama of the city presented to the height of the mountainous part of a television tower clearly gives an idea of the contrasts and the extent of Baku, the horseshoe bay of Baku. The city is shaped like an amphitheater, descending to the Caspian Sea. Tour covers the central part of the city showing the most interesting historical and architectural sites. Visiting of "Old Town” or “Inner City”. The territory of ”Inner City” - 22 hectares, which represents a small fraction of the total area of Baku (44,000 hectares). However, the concentration of architectural and historical monuments, dictates the need for this excursion into a separate and make this part of Baku, perhaps the most interesting to explore. Maiden Tower (XII century), Palace of Shirvanshahs (XV century), Castle Synyk Gala, Caravan Saray, Juma Mosque - this is not a complete list of attractions of the old Baku. Lunch is at Indian restaurant. Transfer back to Hotel. Overnight in Baku. Day 3 – Ateshgah Fire Temple and Yanardag, Burning mountain Breakfast at the hotel. Then we will start our tour with excursion to Ateshgah. The temple of fire worshippers Ateshgah is located at the Apsheron peninsula at the outskirts of Surakhani village in30 km from the centre of Baku and was revered in different times by Zoroastrians, Hindus and Sikhs. -

ARTS on FIRE, FAIRMONT MAGAZINE

ARTS on FIRE Ignited by architecture's biggest stars and a nascent art scene, Baku, Azerbaijan, is ablaze with possibility. By Ellen Himelfarb — Photos by Gunnar Knechtel FAIRMONT BAKU OCCUPIES A SECTION OF THE ICONIC FLAME TOWERS, A TRIO OF MIXED-USE BUILDINGS, DESIGNED BY LONDON- BASED ARCHITECTURAL FIRM HOK 36 Fairmont Magazine Fairmont Magazine 37 Artist faig AHMED My favorite place… Ateshgah fire temple. It an otherwise quiet dining room in Baku’s cobbled old city, Farhad inspires me because it’s one of the most ancient Khalilov and his son Bahram, deep into their third glass of shiraz, are places here. It was constructed and added to debating their preferred exclamation when clinking glasses. Farhad, by different cultures in different ages, which at 68 the elder statesman of contemporary Azerbaijani art, uses the is proved by the Sanskrit writings on the walls Russian “Opa!” perhaps a carryover from his and other ancient symbols. Idays roamingN art circles in Soviet Moscow. Bahram, educated at New York’s Pratt Institute and a youthful 43, prefers the Scandinavian “Skål!” Cultural ambiguities are common in this 23-year-old republic, fought over and occupied for centuries by Persians, Arabs, Mongols and Russians. In the past century alone, the national script has switched from Arabic to Latin, Turkic, Cyrillic and back to the present Turkic. But here in Baku, people are forging a new, vibrant identity and there’s much to look forward to. “Cheers!” we all agree as we drain our glasses. Farhad, for one, is busy. The next morning he’ll depart for his mountain dacha to work on a series of ethereal landscapes. -

The Armenian

FEBRUARY 23, 2013 MirTHErARoMENr IAN -Spe ctator Volume LXXXIII, NO. 32, Issue 4277 $ 2.00 NEWS IN BRIEF The First English Language Armenian Weekly in the United States Since 1932 OSCE Parliamentary Assembly President Sargisian Wins Re-Election Visits Genocide Memorial Azerbaijan, its enemy in a ADL US and Canada YEREVAN (Armenpress) — President of the continuing war over the dis - Organization for Security and Cooperation in puted territory of Nagorno- District Committee Europe (OSCE) Parliamentary Assembly Riccardo Karabagh. Migliori visited the Tsitsernakaberd memorial on Congratulates President But while Sargisian’s vic - February 19, to pay tribute to the memory of tory has been predicted for Armenian Genocide victims. months, there have been Migliori laid a wreath at the memorial and some unexpected develop - By David M. Herszenhorn observed a moment of silence for the memory of ments in the campaign. One 1.5 million victims. He also visited the Armenian challenger, Andreas Genocide Institute-Museum, becoming acquainted YEREVAN ( New York Times and Ghukasian, a political com - with the historical documents of the Armenian Armenpress) — President Serge Sargisian mentator who manages a Genocide. Migliori also planted a tree in the easily won re-election to a second five-year radio station in the capital, Memory Alley. term, according to preliminary returns Yerevan, has been on a Migliori said “The goal of our visit is to get released on Tuesday by the Central hunger strike, demanding acquainted and understand what really happened Election Commission. that the incumbent be in 1915. Many countries are not aware of [the] The returns showed Sargisian with about removed from the ballot. -

TOURISM AS the MAIN FACTOR of SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT of REGIONS in AZERBAIJAN Rufat MAMMADOV Phd

TOURISM AS THE MAIN FACTOR OF SOCIO-ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT OF REGIONS IN AZERBAIJAN Rufat MAMMADOV PhD. Candidate, Business Administration Department, Faculty of Economic and Administrative Sciences Qafqaz University, Azerbaijan [email protected] Abstract After World War II tourism industry grew rapidly. First attempts were centralized on mass tourism but as the industry developed the profits grew rapidly. New forms of tourism occurred. In this respect, the economic and social effects of tourism showed that this industry is one of the main industries after oil sector. Because from the socio-economic point of view the development of tourism in the country leads to reduction of unemployment, improvement of infrastructure, development of communication technologies, increase in nation’s welfare, interaction of cultural values. Together with those benefits thanks to tourism industry the positive image of the country is formulated in the world. Under this positive image it lies political and economical stability. Taking into consideration all these factors, Azerbaijan Government is also developing in this respect. In general, Azerbaijan is one of rare countries in the world possessing 9 climatic zones out of 11, at the same time, her tourism industry grew 22% in 2012 in comparison with the previous year. All these factors give the opportunity to develop tourism and receive benefits from it. It is not by chance Azerbaijan took effective policy in tourism. The regions in Azerbaijan have great opportunities for the development of ecotourism, mountainous tourism, religious tourism, sport tourism, medical tourism, recreational tourism, winter tourism, and sea, sand, sun tourism. The purpose of this article is to show the importance of tourism industry, indicate the current situation of tourism in Azerbaijan, show the current situation in the regions, the current policies and strategies for tourism, and in the conclusion to give proposals for future development of tourism.