Benedict Labre House: 1 952-1 966 In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

EC06-1255 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon Dale T

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Historical Materials from University of Nebraska- Extension Lincoln Extension 2006 EC06-1255 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon Dale T. Lindgren University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist Lindgren, Dale T., "EC06-1255 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon" (2006). Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. 4802. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/extensionhist/4802 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Extension at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Historical Materials from University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. - CYT vert . File NeBrasKa s Lincoln EXTENSION 85 EC1255 E 'Z oro n~ 1255 ('r'lnV 1 List and Description of Named Cultivars in the Genus Penstemon (2006) Cooperative Extension Service Extension .circular Received on: 01- 24-07 University of Nebraska, Lincoln - - Libraries Dale T. Lindgren University of Nebraska-Lincoln 00IANR This is a joint publication of the American Penstemon Society and the University of Nebraska-Lincoln Extension. We are grateful to the American Penstemon Society for providing the funding for the printing of this publication. ~)The Board of Regents oft he Univcrsit y of Nebraska. All rights reserved. Table -

CHAPTER THIRTY the AFFLUENT SOCIETY Objectives a Thorough Study of Chapter 30 Should Enable the Student to Understand: 1

CHAPTER THIRTY THE AFFLUENT SOCIETY Objectives A thorough study of Chapter 30 should enable the student to understand: 1. The strengths and weaknesses of the economy in the 1950s and early 1960s. 2. The changes in the American lifestyle in the 1 950s. 3. The significance of the Supreme Court’s desegregation decision and the early civil rights movement. 4. The characteristics of Dwight Eisenhower’s middle-of-the-road domestic policy. 5. The new elements of American foreign policy introduced by Secretary of State John Foster Dulles. 6. The causes and results of increasing United States involvement in the Middle East. 7. The sources of difficulties for the United States in Latin America. 8. The reasons for new tensions with the Soviet Union toward the end of the Eisenhower administration. Main Themes 1. That the technological, consumer-oriented society of the 1 950s was remarkably affluent and unified despite the persistence of a less privileged underclass and the existence of a small corps of detractors. 2. How the Supreme Court’s social desegregation decision of 1954 marked the beginning of a civil- rights revolution for American blacks. 3. How President Dwight Eisenhower presided over a business-oriented “dynamic conservatism” that resisted most new reforms without significantly rolling back the activist government programs born in the 1930s. 4. That while Eisenhower continued to allow containment by building alliances, supporting anticommunist regimes, maintaining the arms race, and conducting limited interventions, he also showed an awareness of American limitations and resisted temptations for greater commitments. Glossary 1. Third World A convenient way to refer to all the nations of the world besides the United States, Canada, the Soviet Union, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Israel, China, and the countries of Europe. -

UC Berkeley Berkeley Planning Journal

UC Berkeley Berkeley Planning Journal Title Economic Development and Housing Policy in Cuba Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9p00546t Journal Berkeley Planning Journal, 2(1) ISSN 1047-5192 Author Fields, Gary Publication Date 1985 DOI 10.5070/BP32113199 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT AND HOUSING POLICY IN CUBA Gary Fields Introduction Since the triumph of the Cuban Revolution in 1959, Cuba's economic development has been marked by efforts to achieve fo ur basic objectives: I) agrarian reform, including land redistribution, creation of state and cooperative farms, and agricultural crop diversification; 2) economic growth and industrial development, including the siting of new industries and employment opportunities in the countryside; 3) wealth and income redistribution from rich to poor citizens and from urban to rural areas; 4) provision of social services in all areas of the country, including nationwide literacy, access to medical care in the rural areas, and the creation of adequate and affordable housing nationwide. It is important to note that all of these objectives contain an emphasis on rural development. This emphasis was the result of decisions by Cuban economic planners to correct what had been perceived as the most serious ·negative consequence of the Island's economic past--the economic imbalance between town and coun try. 1 The dependence of the Cuban economy on sugar production, with its dramatic seasonal employment shifts, the control of the Island's sugar industry by American companies and the siphoning of sugar profits out of Cuba, the concentration in Havana of the wealth created primarily in the countryside, and the lack of economic opportunities and social services in the rural areas, were the main features of an economic and social system that had impoverished the rural population, creating a movement for change. -

Roman Catholic Church in Ireland 1990-2010

The Paschal Dimension of the 40 Days as an interpretive key to a reading of the new and serious challenges to faith in the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland 1990-2010 Kevin Doherty Doctor of Philosophy 2011 MATER DEI INSTITUTE OF EDUCATION A College of Dublin City University The Paschal Dimension of the 40 Days as an interpretive key to a reading of the new and serious challenges to faith in the Roman Catholic Church in Ireland 1990-2010 Kevin Doherty M.A. (Spirituality) Moderator: Dr Brendan Leahy, DD Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2011 DECLARATION I hereby certify that this material, which I now submit for assessment on the programme of study leading to the award of Ph.D. is entirely my own work and has not been taken from the work of others save and to the extent that such work has been cited and acknowledged within the text of my work. ID No: 53155831 Date: ' M l 2 - 0 1 DEDICATION To my parents Betty and Donal Doherty. The very first tellers of the Easter Story to me, and always the most faithful tellers of that Story. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A special thanks to all in the Diocese of Rockville Centre in New York who gave generously of their time and experience to facilitate this research: to Msgr Bob Brennan (Vicar General), Sr Mary Alice Piil (Director of Faith Formation), Marguerite Goglia (Associate Director, Children and Youth Formation), Lee Hlavecek, Carol Tannehill, Fr Jim Mannion, Msgr Bill Hanson. Also, to Fr Neil Carlin of the Columba Community in Donegal and Derry, a prophet of the contemporary Irish Church. -

Innovator, 1981-04-14 Student Services

Governors State University OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship Innovator Student Newspapers 4-14-1981 Innovator, 1981-04-14 Student Services Follow this and additional works at: http://opus.govst.edu/innovator Recommended Citation Governors State University Student Services, Innovator (1981, April 14). http://opus.govst.edu/innovator/186 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Newspapers at OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Innovator by an authorized administrator of OPUS Open Portal to University Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE GOVERNORS STATE UNIVERSITY INNOVATOR CHIVES Volume 7 Number 18 April 14, 1981 VETS URGE ''STOP THE CUTS'' by Jeff Leanna Along with the massive defaults due to the ten year delimiting date befal ling Many GSU student veterans now the Viet Nam era vets, an additional getting financial assistance to pursue factor may hurt veteran enrollment: the their education may find themselves VEAP system, which replaced the Gl without funds this year. And a great Bill as of January 1st, 1977. many more will lose out in fiscal '82. The VEAP, or Veterans Educat ional This in turn, may affect total veteran Assistance Program, is an educat ional enrollment here. benefits system allowing the ser GSU is not the only school to be vicemen to make contributions of up to experiencing this problem . The $2700 of their own pay toward an in nat ional total of vet enrollment may dividual educat ional fund. The service soon drop off sharply as a result of then matches the amount on a two-for factors independent of all the other one basis, thus giving the vet a total of current economic woes. -

Unity and Diversity in Our Churches

Unity in Diversity In our Churches This document is based on the Key Integration Guidelines as devised by the Parish-Based Integration Project and the Inter-Church Committee on Social Issues. A resource to assist local parishes and congregations with the integration of new residents into their faith communities Unity in Diversity In our Churches Produced by: Adrian Cristea, along with Alan Martin, Robert Cochran and Tony Walsh And further assistance from: Sr. Joan Roddy and Philip McKinley This document was produced as one of the outputs from the “Parish based Integration Project”. This project, which is largely funded by the Integration Unit of the Office of the Minister for State for Integration, was initiated and is managed by the Inter-Church Committee on Social Issues, a committee of the Irish Inter-Church Meeting which represents 15 Churches operating in the island of Ireland. The fifteen member Churches are currently: The Roman Catholic Church, The Antiochian Orthodox Church, The Church of Ireland, The Greek Orthodox Church in Britain and Ireland, The LifeLink Network of Churches, The Lutheran Church in Ireland, The Methodist Church in Ireland, The Moravian Church (Irish District), The Non-Subscribing Presbyterian Church of Ireland, The Presbyterian Church in Ireland, The Religious Society of Friends (Quakers)in Ireland, The Rock of Ages Cherubim and Seraphim Church, The Romanian Orthodox Church in Ireland, The Russian Orthodox Church in Ireland, The Salvation Army (Ireland Division). Further details on the project, and a significant body of relevant resource material, are available on the website at www.iccsi.ie An electronic version of this document is also available on the website in pdf format. -

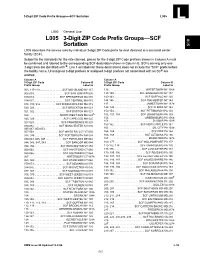

DMM L005 3-Digit ZIP Code Prefix Groups--SCF Sortation

3-Digit ZIP Code Prefix Groups—SCF Sortation L005 L L000 General Use L005 3-Digit ZIP Code Prefix Groups—SCF 005 Sortation L005 describes the service area by individual 3-digit ZIP Code prefix for mail destined to a sectional center facility (SCF). Subject to the standards for the rate claimed, pieces for the 3-digit ZIP Code prefixes shown in Column A must be combined and labeled to the corresponding SCF destination shown in Column B. SCFs serving only one 3-digit area are identified with S; Line 1 on labels for these destinations does not include the “SCF” prefix before the facility name. Unassigned 3-digit prefixes or assigned 3-digit prefixes not associated with an SCF are omitted. Column A Column A 3-Digit ZIP Code Column B 3-Digit ZIP Code Column B Prefix Group Label to Prefix Group Label to 005, 117-119. .SCF MID-ISLAND NY 117 136 . WATERTOWN NY 136S 006-009. SCF SAN JUAN PR 006 137-139. SCF BINGHAMTON NY 137 010-013. SCF SPRINGFIELD MA 010 140-143. .SCF BUFFALO NY 140 014-017. SCF CENTRAL MA 015 144-146. .SCF ROCHESTER NY 144 018, 019, 055 . SCF MIDDLESEX-ESX MA 018 147 . .JAMESTOWN NY 147S 020, 023 . .SCF BROCKTON MA 023 148, 149 . SCF ELMIRA NY 148 021, 022 . SCF BOSTON MA 021 150-154. SCF PITTSBURGH PA 150 024 . NORTHWEST BOS MA 024S 155, 157, 159 . SCF JOHNSTOWN PA 159 025, 026 . SCF CAPE COD MA 025 156 . GREENSBURG PA 156S 158 . DU BOIS PA 158S 027-029. -

Download This Article in PDF Format

A&A 500, 1327–1336 (2009) Astronomy DOI: 10.1051/0004-6361/200911802 & c ESO 2009 Astrophysics Observations of 44 extragalactic radio sources with the VLBA at 92 cm A list of potential calibrators and targets for LOFAR and RadioAstron H. Rampadarath1,2, M. A. Garrett3,2,4, and A. Polatidis1,3 1 Joint Institute for VLBI in Europe (JIVE), Postbus 2, 7990 AA Dwingeloo, The Netherlands e-mail: [rampadarath;polatidis]@astron.nl 2 Sterrewacht Leiden, Leiden University, Oort Building, Neils Bhorweg 2, 2333 CA, Leiden, The Netherlands 3 Netherlands Institute for Radio Astronomy (ASTRON), Postbus 2, 7990 AA Dwingeloo, The Netherlands e-mail: [email protected] 4 Centre for Supercomputing, Swinburne University of Technology, Mail number H39, PO Box 218, Hawthorn, Victoria 3122, Australia Received 5 February 2009 / Accepted 14 March 2009 ABSTRACT Aims. We have analysed VLBA 92 cm archive data of 44 extragalactic sources in order to identify early targets and potential calibrator sources for the LOFAR radio telescope and the RadioAstron space VLBI mission. Some of these sources will also be suitable as “in- beam” calibrators, permitting deep, wide-field studies of other faint sources in the same field of view. Methods. All publicly available VLBA 92 cm data observed between 1 January 2003 to December 31, 2006 have been analysed via an automatic pipeline, implemented within AIPS. The vast majority of the data are unpublished. Results. The sample consists of 44 sources, 34 of which have been detected on at least one VLBA baseline. 30 sources have sufficient data to be successfully imaged. Most of the sources are compact, with a few showing extended structures. -

Code Words to Hide Sex Abuse

CODE WORDS TO HIDE SEX ABUSE A.W. Richard Sipe Revised May 1, 2015 The sexual abuse scandal in the Catholic Church has gone on for so long that a community of researchers, academics, and writers has arisen to study the crisis. Among us are historians, legal scholars, sociologists, psychotherapists and more. But no matter our main discipline, we all have had to struggle with many of the same challenges. The first is coming to terms with the fact that while the Church is famously careful about its records and documents, when it comes to sex and the clergy these documents are obscure to the point of deception. The people who keep the records for the Church are driven to deceive by the clerical culture of celibacy, which forbids all sexual activity by ordained men. Because it is forbidden, clerical sexual activity is always guarded in secrecy, and individuals expend enormous effort to keep it that way. Whenever the secrets are identified within the Church, officials use code words to keep others in the dark while they establish a record that will be useful to them, but not to an outsider. This is why a search of Church documents for evidence of prior knowledge of sexually abusing priests will rarely turn-up the words pedophile, abuser, sex, or any other direct reference to actual sexual or abusive behavior. However, those of us who have worked on this issue both from within and outside the Church have noted similar coded terms and euphemisms being used in documents written around the world and at every level of the ecclesiastical bureaucracy. -

Tree-Ring Analysis of the Anglo-Scandinavian Oak Timbers by Cathy Tyers and Jennifer Hillam

The Archaeology of York Anglo-Scandinavian York 8/5 Anglo-Scandinavian Occupation at 16–22 Coppergate: Defining a Townscape Appendix 3: Tree-Ring Analysis of the Anglo-Scandinavian Oak Timbers by Cathy Tyers and Jennifer Hillam i List of Figures Fig.1 Bar diagram showing the relative positions of the dated ring sequences from Periods 2-5 and their associated felling dates. ................................................................................................................................ 4–6 Fig.2 Summary of the interpreted felling dates or date ranges ............................................................................................. 7 Fig. 3 Histogram showing the distribution of the sapwood values for the 13 measured samples with bark edge and the 2 sigma range of logarithmic values for the sapwood range ........................................... 15 Fig. 4 Histogram showing the distribution of the pseudo-sapwood values derived by assuming simultaneous felling of timbers with sapwood within structures with at least one timber with bark edge and the 2 sigma range of logarithmic values for the sapwood range .................................................... 15 Fig. 5a Diagram comparing the ring sequence length and average growth rates (average ring widths) of all of the dated timbers ............................................................................................................................................... 17 Fig.5b Diagram comparing the ring sequence length and average growth rates (average -

Smallpox in Countries Non-Endemic

CHAPTER 23 SMALLPOX IN NON-ENDEMIC COUNTRIES Contents Page Introduction 1069 Criteria for defining non-endemic countries 1070 The significance of smallpox in non-endemic countries 1071 Actions taken by the non-endemic countries 1071 Actions taken by WHO 1073 Smallpox in Europe, 1959-1978 1073 Sources of importations 1073 Nature of index cases 1075 Delays in notification 1076 Transmission from imported cases 1076 Case studies of importations into Europe 1078 Importations into North America after 1959 1081 Importations into Japan 1081 Importations into recently endemic countries, 1959-1976 1082 Africa 1083 South America 1085 Southern Asia 1085 The 1970-1 972 outbreak in south-western Asia and Europe 1087 Iran 1088 Iraq 1090 Syrian Arab Republic 1090 Yugoslavia 1091 Laboratory-associated outbreaks in the United Kingdom 1095 The London outbreak, 1973 1095 The Birmingham outbreak, 1978 1097 Outbreak of variola minor in the Midlands and Wales, 1966 1098 Conclusions 1100 INTRODUCTION world in the 1960s and early 1970s, cases continued to be imported into smallpox-free In the preceding 11 chapters we have countries. The annual numbers of smallpox systematically reviewed the elimination of cases in most of the larger countries between smallpox from the 31 countries in which it 1920 and 1958 are tabulated in Chapter 8. The was endemic in 1967 and 2 other countries year in which smallpox was last endemic in (Botswana and the Sudan) in which endem- each of these countries is indicated in the icity was re-established after 1967. Because tables; cases occurring after that year were smallpox was endemic in many parts of the due to importations. -

Inventory Control Form

INVENTORY CONTROL FORM Patient Information: Synthes USA Products, LLC Synthes (Canada) Ltd. To order: (800) 523–0322 To order: (800) 668–1119 Date: Hospital: Surgeon: Procedure: Implants TFN–Advanced, Long Nails, 9 mm distal diameter, sterile TFN–Advanced, Long Nails, 10 mm distal diameter, sterile FEMORAL FEMORAL RIGHT LEFT LENGTH NECK ANGLE RIGHT LEFT LENGTH NECK ANGLE 04.037.916S 04.037.917S 260 125° 04.037.016S 04.037.017S 260 125° 04.037.918S 04.037.919S 280 125° 04.037.018S 04.037.019S 280 125° 04.037.920S 04.037.921S 300 125° 04.037.020S 04.037.021S 300 125° 04.037.922S 04.037.923S 320 125° 04.037.022S 04.037.023S 320 125° 04.037.924S 04.037.925S 340 125° 04.037.024S 04.037.025S 340 125° 04.037.926S 04.037.927S 360 125° 04.037.026S 04.037.027S 360 125° 04.037.928S 04.037.929S 380 125° 04.037.028S 04.037.029S 380 125° 04.037.930S 04.037.931S 400 125° 04.037.030S 04.037.031S 400 125° 04.037.932S 04.037.933S 420 125° 04.037.032S 04.037.033S 420 125° 04.037.934S 04.037.935S 440 125° 04.037.034S 04.037.035S 440 125° 04.037.936S 04.037.937S 460 125° 04.037.036S 04.037.037S 460 125° 04.037.938S 04.037.939S 480 125° 04.037.038S 04.037.039S 480 125° 04.037.946S 04.037.947S 260 130° 04.037.046S 04.037.047S 260 130° 04.037.948S 04.037.949S 280 130° 04.037.048S 04.037.049S 280 130° 04.037.950S 04.037.951S 300 130° 04.037.050S 04.037.051S 300 130° 04.037.952S 04.037.953S 320 130° 04.037.052S 04.037.053S 320 130° 04.037.954S 04.037.955S 340 130° 04.037.054S 04.037.055S 340 130° 04.037.956S 04.037.957S 360 130° 04.037.056S 04.037.057S 360 130°