3G As a Sustainability Issue in Swedish Spatial Planning

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kingdom of Sweden

Johan Maltesson A Visitor´s Factbook on the KINGDOM OF SWEDEN © Johan Maltesson Johan Maltesson A Visitor’s Factbook to the Kingdom of Sweden Helsingborg, Sweden 2017 Preface This little publication is a condensed facts guide to Sweden, foremost intended for visitors to Sweden, as well as for persons who are merely interested in learning more about this fascinating, multifacetted and sadly all too unknown country. This book’s main focus is thus on things that might interest a visitor. Included are: Basic facts about Sweden Society and politics Culture, sports and religion Languages Science and education Media Transportation Nature and geography, including an extensive taxonomic list of Swedish terrestrial vertebrate animals An overview of Sweden’s history Lists of Swedish monarchs, prime ministers and persons of interest The most common Swedish given names and surnames A small dictionary of common words and phrases, including a small pronounciation guide Brief individual overviews of all of the 21 administrative counties of Sweden … and more... Wishing You a pleasant journey! Some notes... National and county population numbers are as of December 31 2016. Political parties and government are as of April 2017. New elections are to be held in September 2018. City population number are as of December 31 2015, and denotes contiguous urban areas – without regard to administra- tive division. Sports teams listed are those participating in the highest league of their respective sport – for soccer as of the 2017 season and for ice hockey and handball as of the 2016-2017 season. The ”most common names” listed are as of December 31 2016. -

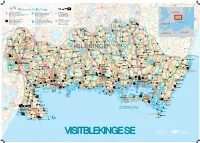

Visit Blekinge Karta

Påryd 126 Rävemåla 28 Törn Flaken Welcome to Blekinge 120 ARK56 Nav - Ledknutpunkt ARK56 Kajakled Blekingeleden Häradsbäck 120 Markerad vandringsled Sandsjön SWEDEN ARK56 Hub - Trail intersection120 Rekommenderad led för paddling Urshult Tingsryd Kvesen Vissefjärda ARK56 Knotenpunkt diverser Wege und Routen Recommended trail for kayaking Waymarked hiking trail ARK56 Węzeł - punkt zbiegu szlaków Empfohlener Paddel - Pfad Markierter Wanderweg 122 www.ark56.se Zalecana trasa kajakowa Oznakowany szlak pieszy Tiken 27 Dångebo Campingplatser - Camping Sydost RammsjönSkärgårdstrafik finns i området Sydostleden Arasjön Campsites - Camping Sydost Passenger boat services available Rekommenderad cykelled Stora Kinnen Halltorp Campingplatz - Camping Sydost Skärgårdstrafik - Passagierschiffsverkehr Recommended cycle trail Hensjön Ulvsmåla Älmtamåla Kemping - Camping Sydost Obszar publicznego transportu wodnego Empfohlener Radweg Baltic Sea www.campingsydost.se www.skargardstrafiken.com Zalecany szlak rowerowy 119 Ryd Djuramåla Saleboda DENMARKGullabo Buskahult Skumpamåla Spetsamåla Söderåkra Lyckebyån Siggamåla Åbyholm Farabol 119 Eringsboda Alvarsmåla Tjurkhult Göljahult Kolshult Falsehult POLAND130 126 GERMANY Mien Öljehult Husgöl Torsåsån Värmanshult Hjorthålan Holmsjö Fridafors R o Leryd Sillhöv- Kåraboda Björkebråten n Ledja n Boasjö 27 e dingen Torsås b y Skälmershult Björkefall å n Ärkilsmåla Dalanshult Hallabro Brännare- Belganet Hjortseryd Långsjöryd Klåvben St.Skälen Gnetteryd bygden Väghult Ebbamåla Alljungen Brunsmo Bruk St.Alljungen Mörrumsån -

LAG – Sydostleader ‐ Sweden

LAG – SydostLeader ‐ Sweden Author: Joel Parde, President of SydostLeader A. Summary table LAG name SydostLeader Lead partner LAG director Storgatan 4, SE‐361 30 Emmaboda, Sweden Joel Parde, LAG President Main European Part of another LAG financial Structural and territorial delivery structure Investment Fund mechanisms Integrated Territorial Multi‐fund EAFRD Investment (ITI) Programme Thematic Financial allocation Priority axes objective(s) CCI number (EUR) concerned concerned European Regional Development Fund (ERDF) Programme 2014SE16M2OP001 537.213 ‐ 9d European Social Fund (ESF) Programme 2014SE16M2OP001 453.142 ‐ 9vi European agricultural fund for rural development (EAFRD) 2014SE06RDNP001 5.287.288 European maritime and fisheries fund (EMFF) 995.275+95.458 Programme 2014SE14MFOP001 (Kalmar & Öland) LAG Strategy LAG Specific territorial Implementation Population covered by Specific thematic focus and focus of the Specific social target Current situation the strategy challenges of the strategy strategy of the strategy (June 2017): . Tackling social Mainly focused on exclusion and . Economic development rural development unemployment Projects under 217 517 . Access to services /Rural areas . Youth initiatives implementation 1 B. Strategy B.1. Area of the CLLD a. Area and population covered by the strategy (See map and figures in B.2.d) The Local development area of – SydostLeader – has a differentiated and varied landscape, from coast and sea to inland with forests and lakes. It extends over eleven municipalities: Emmaboda, Karlshamn, Karlskrona, Lessebo, Nybro, Olofström, Ronneby, Sölvesborg, Tingsryds, Torsås samt Uppvidinge municipality. Thereby the local development area extends over three counties in southeast Sweden: Blekinge, Kalmar and Kronoberg County. An important common feature of the area is the water. The sea, the coast area, rivers and lakes of the districts are part of a unique development area. -

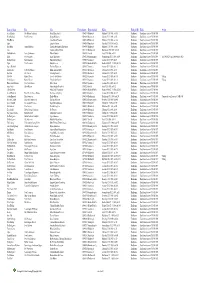

Sammanställning Över Allmänna Vägar I Blekinge Län 2018 I Denna Sammanställning Redovisas Sida

Sammanställning över allmänna vägar i Blekinge län 2018 I denna sammanställning redovisas sida I. Allmänna föreskrifter och upplysningar. 4 II. Sammanställning över allmänna vägar och andra viktigare vägar med bärighetsklasser samt vissa för vägarna gällande lokala trafikföreskrifter 8 III. Förteckning över ej numrerade kommunala gator och vägar som är upplåtna för bärighetsklass 1. 24 IV. Lämpliga leder och gällande inskränkningar för tunga lastbilar och andra större fordon inom vissa tätorter. 25 Bilageförteckning A. Tabell Högsta tillåtna bruttovikter vid bärighetsklass 1 (BK1). 28 B. Tabell Högsta tillåtna bruttovikter vid bärighetsklass 2 (BK2). 30 C. Tabell Högsta tillåtna bruttovikter vid bärighetsklass 3 (BK3). 31 D. Tabell Högsta tillåtna bruttovikter vid bärighetsklass 4 (BK4). 32 E. Kartor Olofström, Sölvesborg, Karlshamn, Ronneby och Karlskrona. lämpliga leder för transport av farligt gods. 33 Turlista: Aspöfärjan 38 Öppetider: Hasslöbron 40 Telefonlista: Länsstyrelsen, Trafikverket, länets kommuner och polisen 41 Blekinge läns författningssamling Länsstyrelsen Länsstyrelsens sammanställning över allmänna 10 FS 2018:8 vägar och andra viktiga vägar i Blekinge län Utkom den 27 med vissa lokala trafikföreskrifter och före- mars 2018 skrifter om bärighetsklasser; I enlighet med 13 kap. 1 § trafikförordningen (1998:1276) har Länssty- relsen upprättat sammanställning över allmänna vägar och andra viktiga vägar i länet. Med stöd av 4 kap. 11 § trafikförordningen har Trafikverket beslutat om bärighetsklasser för allmänna vägar på sätt som framgår av nedan angivna förteckningar. Sammanställningen gäller från den 1 april 2018. Samtidigt upphävs ’Sammanställning över allmänna vägar år 2017 i Blekinge län’, 10 FS 2017:11 4 I. ALLMÄNNA FÖRESKRIFTER OCH UPPLYSNINGAR Axel/boggitryck och bruttovikt Enligt 4 kap §§ 11-14 TrF gäller följande: 11 § Vägar som inte är enskilda delas in i fyra bärighetsklasser. -

LÄN KOMMUN ANTAL Blekinge Län Karlshamn 2 Blekinge Län Karlskrona 7 Blekinge Län Olofström 2 Blekinge Län Ronneby 1 Dalarn

LÄN KOMMUN ANTAL Blekinge län Karlshamn 2 Blekinge län Karlskrona 7 Blekinge län Olofström 2 Blekinge län Ronneby 1 Dalarnas län Avesta 7 Dalarnas län Borlänge 10 Dalarnas län Falun 26 Dalarnas län Gagnef 1 Dalarnas län Hedemora 7 Dalarnas län Leksand 10 Dalarnas län Ludvika 6 Dalarnas län Malung-Sälen 3 Dalarnas län Mora 7 Dalarnas län Orsa 2 Dalarnas län Rättvik 4 Dalarnas län Smedjebacken 5 Dalarnas län Säter 6 Dalarnas län Älvdalen 21 Gotlands län Gotland 22 Gävleborgs län Bollnäs 11 Gävleborgs län Gävle 29 Gävleborgs län Hofors 1 Gävleborgs län Hudiksvall 15 Gävleborgs län Ljusdal 2 Gävleborgs län Nordanstig 2 Gävleborgs län Ovanåker 7 Gävleborgs län Sandviken 18 Gävleborgs län Söderhamn 5 Hallands län Falkenberg 4 Hallands län Halmstad 9 Hallands län Hylte 1 Hallands län Kungsbacka 8 Hallands län Varberg 4 Jämtlands län Berg 30 Jämtlands län Bräcke 1 Jämtlands län Härjedalen 116 Jämtlands län Krokom 113 Jämtlands län Ragunda 3 Jämtlands län Strömsund 74 Jämtlands län Åre 79 Jämtlands län Östersund 146 Jönköpings län Aneby 1 Jönköpings län Eksjö 4 Jönköpings län Gislaved 4 Jönköpings län Gnosjö 1 Jönköpings län Jönköping 9 Jönköpings län Nässjö 4 Jönköpings län Tranås 7 Jönköpings län Vaggeryd 1 Jönköpings län Vetlanda 4 Jönköpings län Värnamo 4 Kalmar län Borgholm 1 Kalmar län Hultsfred 1 Kalmar län Högsby 1 Kalmar län Kalmar 6 Kalmar län Mönsterås 1 Kalmar län Mörbylånga 4 Kalmar län Nybro 5 Kalmar län Oskarshamn 8 Kalmar län Torsås 2 Kalmar län Vimmerby 2 Kalmar län Västervik 1 Kronobergs län Alvesta 4 Kronobergs län Ljungby 1 -

BB-I-Blekinge-Karlshamn-1904 1920

Barnets Namn Far Mor Födelsedatum Kyrkobokförd Källa Född på BB Källa Övrigt Astrid Elisabet Nils Nilsson Lindblom Berta Håkansdotter 19040119Hällaryd fs Hällaryd CI:11 1904, sid 133 Karlshamn Karlshamns lasarett C-SCB 1904 Bernt Richard Sven Svensson Bengta Nilsdotter 19040208Mörrum fs Mörrum CI:11 1904, sid 45 Karlshamn Karlshamns lasarett C-SCB 1904 Edla Malena Anna Maria Persdotter 19040310 Hällaryd fs Hällaryd CI:11 1904, sid 134 Karlshamn Karlshamns lasarett C-SCB 1904 Algot Augusta Nilsson 19040609Jämshög fs Jämshög CI:10 1904, sid 225 Karlshamn Karlshamns lasarett C-SCB 1904 Karl Julius August Hallberg Karolina Bernhardina Karlsdotter 19040903 Hällaryd fs Hällaryd CI:11 1904, sid 141 Karlshamn Karlshamns lasarett C-SCB 1904 Lisa Carolina Alfrida Olsson 19041104 Karlshamn fs Karlshamn CI:10 1904, sid 229 Karlshamn Karlshamns lasarett C-SCB 1904 Dödfödd flicka Ludvig Johansson Maria Olsdotter 19041103Åryd fs Åryd CI: 9 1904, sid 121 Karlshamn Karlshamns lasarett C-SCB 1904 Klara Per Persson dy Ingar Johnsdotter 19050120 Gammalstorp fs Gammalstorp CI:11 1905, sid 98 Karlshamn Karlshamns lasarett C-SCB 1905 Står 19050220 som födelsedag i C-SCB Dödfödd flicka Karl Johansson Maria Klemedsdotter 19050409Asarum fs Asarum CI:12 1905, sid 92 Karlshamn Karlshamns lasarett C-SCB 1905 Signe Jöns Sonesson Maria Jönsson 19050502 Bräkne-Hoby fs Bräkne-Hoby CI:15 1905, sid 229 Karlshamn Karlshamns lasarett C-SCB 1905 Agnes Elisabeth Karolina Håkansson 19051027Asarum fs Asarum CI:12 1905, sid 112 Karlshamn Karlshamns lasarett C-SCB 1905 Elin Kristina -

A Facilitating Platform for Energy & Climate Change Programs – A

Master’s Thesis in Strategic Leadership towards Sustainability (SL2403) A Facilitating Platform for Energy & Climate Change Programs – a Case within Municipalities in Southeast Sweden Rajeev Akireddy, Yuan Zhi, Evelyne Lyatuu School of Engineering Blekinge Institute of Technology Karlskrona, Sweden 2011 Primary Supervisor: Dr. Henrik Ny Secondary Supervisor: Marco Valente i A Facilitating Platform for Energy & Climate Change Programs – a Case within Municipalities in Southeast Sweden Rajeev Akireddy, Yuan Zhi, Evelyne Lyatuu School of Engineering Blekinge Institute of Technology Karlskrona, Sweden 2011 Thesis submitted for completion of Master of Strategic Leadership towards Sustainability, Blekinge Institute of technology, Karlskrona, Sweden. Abstract: Focus on municipal level planning has increased in the recent years. Municipal governments are primarily responsible for such planning and they do have the biggest responsibility of driving the entire municipality towards sustainability. In this research project we provide a study on some of the gaps and challenges in the current procedures faced by a few municipalities within Southeast Sweden with respect to Energy and climate change planning and implementation. It was observed that the current engagement practices, communication, and alignment of goals could potentially hinder the municipality from achieving the overall goals of sustainability. Furthermore, a complementing facilitating platform was suggested that would give municipal governments an opportunity to intervene and address some of these gaps and challenges to establish structure and control on activities, towards a sustainable municipality. Keywords: municipality, energy, climate change, policy, gaps, challenges, strategy i Statement of Contribution This thesis was the result of our interests and emergent opportunities, the topic emerged from the research team’s strong shared interest in discovering newer approaches for municipalities working on Energy and climate change issues. -

2011 Karlshamn

Karlshamn Officiell Turistguide Official Tourist Guide Offizieller Touristenguide guide Oficjalny turystycznych 2011 2 På dessa sidor presenterar vi Karlshamns utbud för dig som besöker oss. Här hittar du värdefull information för din vistelse, både när det gäller möten & affärer och en semester fylld av upplevelser. Vårt mål är att du ska trivas, inspireras och göra precis som många andra av våra gäster – återkomma år efter år. Vi på turistbyrån hjälper dig gärna vidare – välkommen att besöka oss! Lena Axelsson, Turistchef och personalen på Karlshamns Turistbyrå Welcome to Karlshamn – the commercial town by the sea! On these pages we present what Karlshamn has to offer you as a visitor. You will find useful information for your stay, whether you are here for business or pleasure. Our aim is to help you enjoy your stay, be inspired and do just as many of our guests – return to Karlshamn. Please visit us at the Tourist Information Office – we are more than happy to assist you! 3 Hitta ditt drömställe 4 Find your favorite spot | Entdecke dein Paradies Znajdź swój ulubiony zakątek Upplev skärgården 12 Discover the archipelago | Erlebe die Schären Innehåll Poznaj szkiery Tidtabeller, skärgården 13,18-19 Timetable for the archipelago| Zeitplan für den Schären | Rozkład rejsów statków na szkiery Njut av en riktig svensk sommar 20 Enjoy a real Swedish summer | Genieße den schwedischen Sommer | Rozkoszuj się szwedzkim latem Evenemang 26 12 26 Events | Veranstaltungen | Imprezy Historia 34 History | Geschichte | Historia Sevärdheter 38 52 Sightseeings -

Baltic Trade and Transport – Karlshamn May 22–23

I N V I T A T I O N Baltic trade and transport Conference fee SEK 950 plus VAT. The fee includes seminars, coffee and lunch. – Karlshamn May 22–23 SEK 450 plus VAT. Dinner at Eriksbergs wildlife and naturepark. Register via www.logistikkarlshamn.se For more information, please call +46 (0)454-816 27 or contact by e-mail [email protected] Day 1 Day 2 09.30 Registration & coffee 09.00 Increased efficiency of cargo flows through nodes Moderator Roger Lindau 10.00 Conference opening – Innovative technical solutions Moderator, Dr. Roger Lindau. Transportation & Logistics Manager Northern Lawrence Henesey, PhD Intelligent logistics, Blekinge Institute of Technology Europe at ABB – Welcome to Karlshamn 09.45 Coffee Sven-Åke Svensson, Mayor of Karlshamn – Presentation of the East west transport corridor association 10.15 – ICT/ITS – better access to real time information for increased Algirdas Šakalys, President East West Transport Corridor Association efficiency – Lithuanian perspective of east-west business Jonas Sundberg, Sweco Mr Eitvydas Bajorūnas, Ambassador of Republic Lithuania in Sweden – Increased efficiency with focus on environment and quality, Magnus Swahn, Conlogic AB 10.40 Trade patterns and logistics in Europe – Driving forces in modern Supply Chains 10.55 Pause Pär Sandström, PSandström Logistics AB 11.10 – Impact of innovative technologies on the customs process – Outcomes of TEN-T the Motorways of the Sea project Laima Greičiūnė, EWTCA Secretariat José Laranjeira Anselmo, Advisor PP21 – Motorways of the Sea, and -

Mise En Page 1

Services for the public Augment How is it possible for people with disabilities to participate in society and make the region more accessible? DESCRIPTION OF THE INITIATIVE KEY FIGURES Region: Blekinge (Sweden) Augment started out as a research and development project Population: 152 000 inhabitants in collaboration between the regional university and one of the 5 municipalities – Karlskrona, Ronneby, five municipalities in the region (Ronneby). In 2010 a Karlshamn, Sölvesborg and Olofström proof-of-concept project was initiated and the services further Area: 2 941 km² developed. Augment is currently being tested on local, regional Density: 51 inhabitants/km² and national levels by a number of user groups. In the first Main economies: Manufacturing industry, IT implementation the services have been developed for a website and telecom industry, tourism and fishing and as a mobile application for Android. The accessibility industry content is user-driven and relies on the active participation and interest of the users of the services. Citizens can easily get KEY WORDS RELATING TO THE timely and accurate information about the status of PROJECT accessibility in a specific location and also contribute by Location-based services, accessibility, updating the information. social media, user-driven content, participatory design, disability services MAIN RESULTS l Augment web-site created CONTEXT AND OBJECTIVES l Augment mobile service created Until now mobile technologies have not been used for improving accessibility in the region. Augment provides -

Guide to Ronneby Brunn Area

Guide to THE RONNEBY BRUNN AREA and THE HARDWOOD COAST NATURE • CULTURE • EXCURSIONS 1 Introduction We are all responsible for managing the countryside, our environment, with a long-term perspective, so that we can preserve its values for future generations. Here in Blekinge we have a special responsibility for safeguarding the unique coastal deciduous forests. Since the 19th century, Brunnsparken and the surrounding forests have formed an important part of what we now call “Ronneby, the modern health resort”. Thanks to its well-preserved deciduous forest, Brunnsskogen is a top-class meeting place, which stimulates the senses and invites to active leisure activities, social encounters and tranquil recreation. For us, Brunnsskogen is a driving force for an attractive and growing Ronneby and something that all residents of the municipality can be proud of. Some years ago, the area became a nature reserve managed by Ronneby Municipality, and now it is also a pilot are for the Attractive Hardwoods project. Being out in the countryside area, whether it is just a few hours in a park or a whole day’s walking on forest trails, makes us feel good, both physically and mentally. I therefore hope that this guide will inspire more people to go out and experience all that Blekinge’s nature has to offer. Roger Fredriksson Mayor, Ronneby Municipality 2 3 Guide contents PAGES 4–13: The Hardwood Coast; its natural values and what it has to offer PAGES 14–16: Valuable nature in the Ronneby area PAGES 17–29: Ronneby Brunnspark Culture Reserve PAGES 30–32: -

CEF 2019 Transport Call

Connecting Europe Facility (CEF) 2019 TRANSPORT CALL Proposal for the selection of projects September 2019 Innovation and Networks Executive Agency Innovation and Networks Executive Agency (INEA) http://ec.europa.eu/inea European Commission - Directorate General for Mobility and Transport http://ec.europa.eu/transport Page 2 / 60 Table of Contents Commonly used abbreviations ......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 7 CEF priorities ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 7 Multi-Annual and Annual Work Programmes............................................................................................................................................................................................... 7 2019 CEF Transport call – Structure and particularities.........................................................................................................................................................................